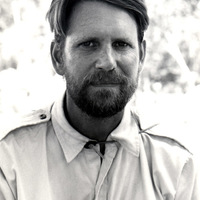

David Freidel

Washington University in St. Louis, Anthropology, Faculty Member

- Professor of Anthropological Archaeology and Maya Archaeologist. Graduated from Harvard College and the GSAS with a P... moreProfessor of Anthropological Archaeology and Maya Archaeologist. Graduated from Harvard College and the GSAS with a PhD on the settlement patterns of Cozumel Island. Mentor of 30 doctoral students in archaeology. Director of long-term field projects in Belize, Mexico and Guatemala.edit

This volume is an articulate critique of the banal functionalism of New Archaeology (especially "ecological," "settlement," and "human adaptation" approaches), and the shallow determinism of American... more

This volume is an articulate critique of the banal functionalism of New Archaeology (especially "ecological," "settlement," and "human adaptation" approaches), and the shallow determinism of American materialists (the band-chiefdom-state evolutionists). In the words of the editor, Ian Hodder, it is a "reactionary" tribute to V. G. Childe. The 15 papers—some data-heavy, rigorous and sophisticated; some theoretically dense (in materials with which archaeologists are probably totally unfamiliar, such as semiotic theory)— focus on context and meaning, on artifact as ideology. And apart from two chapters (these the poorest ones), each contribution involves attention to issues in contemporary Marxism—from Althusserian critique to research in iconics and social history. Symbolic and Structural Archaeology is intelligent, informed, and it merits study and discussion. The volume is occasion for general commentary on the results of the Cambridge Seminar and on the implications for archaeology. Importantly, as Leone notes in his concluding statement, "structure" here is far more Marx than it is Levi-Strauss. Similarly, Childe is more celebrated for his insertion of politics into archaeology than for his study of evolution or any specific analysis. But unfortunately there is not the accompanying political responsibility this might seem to suggest. Although this might be expected in the Philistine world of science worship where political analyses are dismissed, I do not think this accounts for the irresponsibility here. One minimal example of their irresponsibility is the use of "man" to mean "person." But theoretically, the implications are far reaching, for by not establishing explicit political reading and critique, the authors are forced to retreat to rationalist determination, thereby accepting the classical ideology/ knowledge dichotomy with its epistemological appeal. Despite their trappings, then, these questions are not political (i.e., about better ways to arrange social relations), but, rather, are about better ways to elucidate truth or reality. And this means political readings and political discourses (objections, say, to certain social relations by assigning certain significance to artifacts) are avoided in favor of debates about the "concealed," "real" social relations, "misrepresentations," "illusions," "inverted" social relations, or elucidation of existing contradictions or structures that lie hidden. That these notions are conventional Marxist orthodoxy does not privilege them from identity with the standard range of empiricist discovery techniques; the revelation or revealing of structures or ideologies is epistemologically identical to the discovery of facts. Politics, then, is reduced to determination in political guise. It can be achieved with the methodologies now in place, the testable "truth" and reality correspondence that is the object of New Archaeology. Knowledge is what "we" produce, ideology is what "they" (the human social form whose remains we investigate, or archaeologists with whom we disagree) produced. Moreover, the archaeological object is premised in conventional notions of totality ("society," "modes of production") rather than in strategically/theoretically posited social relations. Thus functional processes must be evoked, necessary to the continuity or existence ("reproduction," "articulation") of such totality. There is no fundamental epistemological way in which the articulations of modes of production or the unfolding of contradictions or structures differ from the condemned techno-eco-demo-coefficients or entropy determinations. Artifacts-as-ideology, if taken seriously as a political project, means that there can be no objects independent of discourse about such objects. This is not debate about existence; it is, rather, an issue of conditions (politically conferred) under which such objects can exist.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests: Archaeoastronomy and Arch

This chapter highlights some key themes of the chapters in the book, such as markets, low-density urbanism, Terminal Classic rural households, comparing Tikal and Chunchucmil, and comments on the advances and breakthroughs in recent... more

This chapter highlights some key themes of the chapters in the book, such as markets, low-density urbanism, Terminal Classic rural households, comparing Tikal and Chunchucmil, and comments on the advances and breakthroughs in recent scholarship on Maya political economy.

Research Interests:

The significance of E Groups to the ancient Maya has been recognized for almost a century. Placed facing each other across a formal plaza, a western pyramid and a long eastern platform that usually supports three structures form the... more

The significance of E Groups to the ancient Maya has been recognized for almost a century. Placed facing each other across a formal plaza, a western pyramid and a long eastern platform that usually supports three structures form the architectural arrangement known as an E Group. The solar alignments within an E Group were recognized first at Uaxactún, Guatemala, and were interpreted to mean that the entire complex functioned as a giant calendrical device. Because this architectural arrangement could be recognized at other Maya sites, it became viewed as central to the rise of Maya civilization. This chapter briefly reviews the history of E Group research and sets the stage for the more detailed studies that follow.

Research Interests:

<p>The material symbol-systems of the Preclassic (1000 BCE–250 CE) Maya reflect a focus on the daily and annual cycles of the sun and the relationship between these and the cycles of the agrarian year, particularly as represented in... more

<p>The material symbol-systems of the Preclassic (1000 BCE–250 CE) Maya reflect a focus on the daily and annual cycles of the sun and the relationship between these and the cycles of the agrarian year, particularly as represented in the anthropomorphic Maize God. The Maya sun gods, the Maize God, and the solar avatar of the Creator God Itzamnaaj or the Principal Bird Deity are depicted in architectural decoration, murals and carvings in Preclassic contexts. They are also depicted in later Classic Period (250-950 CE) contexts. I explore these images and ideas to show that the E Group phenomenon was one part of the development of a pan-peninsular religion, worldview and ideology establishing the basis for Preclassic Maya rulership. Finally, I explore the prospect that the site of Cerros has an Eastern Triadic Structure, Structure 29, rather than an E Group. I propose on iconographic grounds that this building is a solar commemorative structure and possibly a bundle house.</p>

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Recently several models have been proposed for the origin and evolution of lowland Maya civilization. These models share a basic spatial framework, the culture area, which is logically tied to a particular theoretical approach to the... more

Recently several models have been proposed for the origin and evolution of lowland Maya civilization. These models share a basic spatial framework, the culture area, which is logically tied to a particular theoretical approach to the emergence of lowland Maya civilization. The culture area approach rests on the premise that sociocultural innovation occurs as a localized response to local natural and social conditions. Such innovation subsequently diffuses outside the local area through successful competition with alternatives. The empirical archaeological expectations of models based upon this approach are not satisfied at the site of Cerros, a Late Preclassic center on the coast of northern Belize. An alternative approach, the interaction sphere, better accommodates the evidence from Cerros and other Preclassic sites in the Maya Lowlands. The culture area models, the evidence from Cerros, and the interaction sphere approach and its theoretical ramifications are discussed.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

The Cozumel Archaeological Project was one of the first attempts to apply some of the tenets and perspectives of processual archaeology to the ancient Maya. Its goals were to ". . . broaden and change traditional conceptions of... more

The Cozumel Archaeological Project was one of the first attempts to apply some of the tenets and perspectives of processual archaeology to the ancient Maya. Its goals were to ". . . broaden and change traditional conceptions of ancient Maya trade and to increase our understanding of the nature of the Decadent period (Late Postclassic) in Yucatan" (p. xv). Surveys and excavations were conducted on Cozumel Island off the coast of Quintana Roo, Mexico in an effort to study the structure and functioning of the circum-Yucatan maritime commercial system the investigators believe functioned in late Precolumbian times. This first volume in the project's final report series deals with the architectural remains and settlement patterns identified during the survey. A short introductory chapter contains general information about Cozumel and the project, outlines the mapping procedures, and explains the nomenclature used. This is followed by chapters describing various kinds of structures and the assemblages they form; information on eight of the best known sites; a summary of settlement patterns; and a functional synthesis of Cozumel society during the Decadent period. Illustrations include 36 photographs and 51 line drawings that show building ground plans, site maps, selected excavation profiles, and other features. The presentation includes detailed descriptions of the remains and well-reasoned interpretations of them based upon archaeological data and contact period ethnohistoric information. The data are presented clearly and the functional interpretations of buildings constitute a real contribution to our knowledge of Maya architecture and life. Unfortunately, the monograph is plagued with two serious problems. One relates to the illustrations. Many of the structural plans lack legends or keys and at times are virtually impossible to understand. Furthermore, no map of San Gervasio, one of the largest sites on the island, is provided; instead the reader is referred to one published in a preliminary report. Fortunately, I had mine at hand but its absence in the present volume places an unreasonable burden on the reader. The second problem is the complete lack of a discussion of field methodology. The single paragraph on mapping techniques is far too scanty to be useful. Furthermore, we are never told what survey techniques were used; how the sites were discovered; or how much of the island was actually sampled. This book and other Project publications suggest that the sample includes most of the larger sites and an unspecified percentage of smaller sites on the island. The methodology as I reconstruct it does not bother me as much as the fact that it is not discussed. This information is essential if the mass of carefully analyzed architectural and site data is to be truly useful. Despite these shortcomings the book is a significant contribution to our knowledge of the Late Postclassic Maya and together with the forthcoming volumes on other aspects of the Project should provide major new insights into Precolumbian economics and trade.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

This chapter highlights some key themes of the chapters in the book, such as markets, low-density urbanism, Terminal Classic rural households, comparing Tikal and Chunchucmil, and comments on the advances and breakthroughs in recent... more

This chapter highlights some key themes of the chapters in the book, such as markets, low-density urbanism, Terminal Classic rural households, comparing Tikal and Chunchucmil, and comments on the advances and breakthroughs in recent scholarship on Maya political economy.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

This summary chapter weaves together the themes presented by various authors into a broader view of greater Mayab. The author draws on his wide experience excavating on Cozumel Island and in Yucatan, Belize, and Guatemala to link Chetumal... more

This summary chapter weaves together the themes presented by various authors into a broader view of greater Mayab. The author draws on his wide experience excavating on Cozumel Island and in Yucatan, Belize, and Guatemala to link Chetumal Bay, situated on the eastern edge of the region, to more distant Maya polities across time and space. He follows the themes of waterborne travel, noted in new discoveries at El Achiotal, the precocious early development of a long distance exchange network at Yaxuna and elsewhere, the rise of the El Mirador polity in the Late Preclassic, and the fortunes of the Classic era Kaanal kingdom to link individual site histories to broader historical trends.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

... With the help of the police and gov-ernment officials, the few Amhara re-maining in Dimam after the Italian-Ethiopian war and the abolition of slav-ery continued to deny the Dime access to firearms, while continuing to provide the... more

... With the help of the police and gov-ernment officials, the few Amhara re-maining in Dimam after the Italian-Ethiopian war and the abolition of slav-ery continued to deny the Dime access to firearms, while continuing to provide the Bodi with weapons. ... A Maya Site ...

Research Interests:

... I came into ar-chaeology with interests of that nature-history, litera-ture, and so forth-as opposed to coming in from the natural sciences. Lew Binford, as I understand it, came in from forestry. Ben Rouse was more interested in the... more

... I came into ar-chaeology with interests of that nature-history, litera-ture, and so forth-as opposed to coming in from the natural sciences. Lew Binford, as I understand it, came in from forestry. Ben Rouse was more interested in the natural sciences. ...

Research Interests:

It is argued in this chapter that the idea of “empire” was established in the Maya lowlands by the Kaanal lords of El Mirador with their first regional hegemony. The idea of empire is associated with the evolution of Maya kingship and can... more

It is argued in this chapter that the idea of “empire” was established in the Maya lowlands by the Kaanal lords of El Mirador with their first regional hegemony. The idea of empire is associated with the evolution of Maya kingship and can be discerned clearly in the Classic period. It is also proposed that the Kaanal kings of the Preclassic Period established important cultural patterns in the central and northern lowlands including a form of divine kingship institutionalized around councils and transformation rituals which could not be claimed by simple kin succession from the prior king. The political economic obligations of Preclassic Maya kingship strongly reinforced collective efforts such as risk-reducing marketplace distribution of food and other vital commodities. It also encouraged the establishment of regional hegemonic hierarchies that facilitated administration of common political economic objectives.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests: Humanities and Art

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests: History and Archaeology

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

An academic directory and search engine.

Research Interests:

Olivia Navarro-Farr and colleagues explore another example of how the Snake Kings manipulated the political landscape of the Classic period with a fascinating case study in ancient Maya queenship at Waka’ in Chapter 10. Waka’ was first... more

Olivia Navarro-Farr and colleagues explore another example of how the Snake Kings manipulated the political landscape of the Classic period with a fascinating case study in ancient Maya queenship at Waka’ in Chapter 10. Waka’ was first embroiled by the geopolitics of the lowlands during the Teotihuacan entrada of AD 378, after which the kingdom was apparently incorporated into the New Order’s political network based at Tikal. Kaanul subsequently brought Waka’ into its hegemony near the end of the Early Classic period with the marriage of the first of at least three royal Kaanul women to kings of Waka’. Beyond simply telling this story, Chapter 10 explores monumentality in two ways. First, Waka’ is presented as a contested node on the vast political and economic network of the Classic period, its importance evident in its role in the entrada, the deliberate and long-term strategy to integrate it into the Kaanul hegemony through royal marriage, and Tikal’s Late Classic star war conque...

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests: Archaeology and Maya

Research Interests:

Ancient America Special Publication Number One Julia Guernsey and Kent Reilly, editors Boundary End Archaeology Research Center 2006