Alla Vronskaya

Illinois Institute of Technology, College of Architecture, Faculty Member

- Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Architecture, Department Memberadd

- Architecture, Art History, Aesthetics, Architectural History, Modern Art, Art and Science, and 16 moreLandscape History, Modernist Architecture (Architectural Modernism), Affect Theory, Affect (Cultural Theory), Affect/Emotion, Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, Soviet Architecture, Russian Architecture, Soviet art, Socialist Realism, Constructivism, History of Soviet Architecture, Russian Studies, Russian Intellectual History, Posthumanism, and Manfredo Tafuriedit

“Anti-Architectures of Self-Incurred Immaturity: A House-Spirit in a Plattenbau,” Second-World Postmodernisms: Architecture and Society Under Late Socialism, ed. by Vladimir Kulic (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), 143-159.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Trans 30: 90-97

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

This article focuses on Moisei Ginzburg’s competition entry for the Central Park of Culture and Leisure in Moscow (1931), assessing its nature as a utopian landscape. It demonstrates how the program of the project emerged from the debates... more

This article focuses on Moisei Ginzburg’s competition entry for the Central Park of Culture and Leisure in Moscow (1931), assessing its nature as a utopian landscape. It demonstrates how the program of the project emerged from the debates on modernist town planning as an attempt to adapt ideas developed in the course of these debates to existing urban context. Emerging prior to the rest of the modernist urban environment, the park assumed the role of representing the settlement of the future within the city of the past, while simultaneously forming a part and parcel of the urban system to come. It was both inscribed into the modernist system of the zonal division of the city as the recreation zone and itself divided into separate zones, becoming a miniature model of an ideal modernist city of the future. The project was based on the principles of “disurbanism,” an approach to town planning, which Ginzburg earlier developed in his project of the Green City near Moscow (1930). Following the theoretician of disurbanism Mikhail Okhitovich, Ginzburg declared the individual (rather than the family or the group) the basic unit of society, and consequently, personal development became the major mission that his park was to perform. As a result, the Park of Culture and Leisure became not a site, but a mechanism of personal and urban transformation.

Research Interests:

This article assesses the legacy of Soviet landscape architect Militsa Prokhorova (1907-1959), who in the late 1920s-early 1930s was among those responsible for the development of the concept of “park of culture and leisure” as the basic... more

This article assesses the legacy of Soviet landscape architect Militsa Prokhorova (1907-1959), who in the late 1920s-early 1930s was among those responsible for the development of the concept of “park of culture and leisure” as the basic type of Soviet public park. The article demonstrates how Prokhorova’s education at the workshop of Nikolai Ladovskii at Moscow VKhUTEMAS, and Ladovskii’s psychological theory of urban design in particular, impacted her vision of goals and methods of the architecture of Soviet public park.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests: Body Image and Lenin

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

The expression ‘regular English garden’ even nowadays sounds like an oxymoron, although the rehabilitation of pre-landscape gardens started in Great Britain nearly a century and a half ago, hand-in-hand with the study of their history.... more

The expression ‘regular English garden’ even nowadays sounds like an oxymoron, although the rehabilitation of pre-landscape gardens started in Great Britain nearly a century and a half ago, hand-in-hand with the study of their history. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, garden history turned into one of the most important constituents of design theory; the main sources of information

Research Interests:

Close Document Image Close Document Printer Image Print This Document! Conservation Information Network (BCIN). Author: Vronskaya, Alla Title Article/Chapter: "Noviy Kychyk-Koy" Title of Source: Historic Gardens... more

Close Document Image Close Document Printer Image Print This Document! Conservation Information Network (BCIN). Author: Vronskaya, Alla Title Article/Chapter: "Noviy Kychyk-Koy" Title of Source: Historic Gardens Foundation ...

Two recent exhibitions — at the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow and at Tchoban Foundation Museum for Architectural Drawing in Berlin — mark a renewed interest in the so-called “paper architecture,” utopian architectural... more

Two recent exhibitions — at the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow and at Tchoban Foundation Museum for Architectural Drawing in Berlin — mark a renewed interest in the so-called “paper architecture,” utopian architectural drawings produced by young Soviet architects for Western and Japanese competitions and exhibitions during the 1980s. Some of its protagonists, such as Alexander Brodsky, are internationally famous today, others comprise the elite of Russian architecture. Reflecting upon the sources of its success, this presentation will suggest that paper architecture responded to a trauma of modern society that Max Weber famously characterized as disenchantment. Having displaced the magical from human life, science and rationality opened in the modern consciousness a painful wound. In the hyper-modernized society such as the 1980s USSR, where religion was stigmatized and where architecture was largely reduced to standardized construction, the need in the magical was particularly acute. My presentation will argue that paper architecture crafted the mystical out of the banality of the everyday. I will focus on one project, the “Exhibition House” (1981) by Mikhail Belov and Maxim Kharitonov, demonstrating its simultaneous indebtedness to Vincenzo Scamozzi’s decoration of Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza and Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Relying on strategies developed in conceptual art during the 1970s, paper architecture exposed, exaggerated and mystified the comical absurdity of everyday life in order to create a reenchanted world out of the very products of disenchantment.

Research Interests:

In 1923, at the height of Anatoly Lunacharsky’s importance as the Commissar of Culture and Education, his “Foundations of Positive Aesthetics” (1903) was reprinted without revisions, impacting the generation of the “heroic” Soviet... more

In 1923, at the height of Anatoly Lunacharsky’s importance as the Commissar of Culture and Education, his “Foundations of Positive Aesthetics” (1903) was reprinted without revisions, impacting the generation of the “heroic” Soviet avant-garde. My presentation will examine Lunacharsky’s theory, exposing its origins in the “empiriocriticist” epistemology of German-Swiss philosopher Richard Avenarius. I will demonstrate that Avenarius’s principle of the “least measure of force” was enriched by Lunacharsky with a Nietzschean exaltation of life, leading to a revolutionary aesthetics that empowered both the artist and the spectator.

Research Interests:

The late 1980s marked the last years of Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika—a liberalization of Soviet regime and the opening of the country to the West. These new political and economic opportunities caused excitement, enthusiasm, and... more

The late 1980s marked the last years of Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika—a liberalization of Soviet regime and the opening of the country to the West. These new political and economic opportunities caused excitement, enthusiasm, and interest in Russian culture and history. My presentation will examine the significance of this historical turn—and the ensuing familiarity with the formal language of the Russian avant-garde—for Western, particularly American, architecture at the moment of its disentchantment in postmodernist historicism; and vice versa—I will assess the significance of the mid- and late-1980s debate about postmodernism for the reception of the Russian avant-garde in the West. I will focus on the “Deconstructivist Architecture” exhibition (1989) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York to uncover how the image of early-modernist Soviet architecture was fabricated by its curators Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley through exhibition strategies and the accompanying catalog. I will demonstrate that, for Wigley, “deconstructivism”—a term that he invented to describe the architecture of Peter Eisenman, Bernard Tschumi, Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid, Coop Himmelblau, and Daniel Libeskind—was less a referral to the philosophy of Jacques Derrida than to the aesthetics of Russian Constructivism, a reincarnation of which he discovered in the work of these architects. Moreover, Wigley suggested to view the years 1918-1920 as a period of “early Constructivism,” which, according to him, demonstrated energy and flexibility that the later, high, modernism lacked. By inventing this historiographic category (and freely assigning various projects to it) Wigley created an icon of humanist and dynamic modernism—an appealing model that allegedly coexisted with the first post-Revolutionary years, and which was later abandoned by architecture just as the true ideals of socialist humanism were abandoned by the totalitarian Soviet regime.

Research Interests:

My presentation critically examines the historiography of Soviet Interwar art and architecture to question the opposition of the avant-garde and totalitarianism, which has appeared as its recurring theme from the 1960s on. I argue that... more

My presentation critically examines the historiography of Soviet Interwar art and architecture to question the opposition of the avant-garde and totalitarianism, which has appeared as its recurring theme from the 1960s on. I argue that this opposition conflates aesthetic and political discourses and is rooted in Cold-War ideology. As an example of its inability to adequately represent the complexity of cultural development in Interwar Russia, I assess the problems posed by the architecture of the First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932). Finally, I argue for an alternative analytic model—for an approach that explains rather than judges, and situates architecture within the context of political, economic, and intellectual life, comparing, not juxtaposing, Soviet modernism, including its Stalinist versions, to its Western counterparts.

Research Interests:

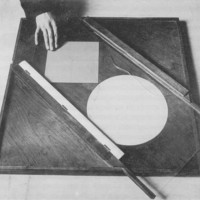

My presentation will address the psychophysiological theory of architecture, developed by architect and VKhUTEMAS pedagogue Nikolai Ladovskii and his followers (the so-called Rationalists) in the 1920s and 1930s. Predicated on the notions... more

My presentation will address the psychophysiological theory of architecture, developed by architect and VKhUTEMAS pedagogue Nikolai Ladovskii and his followers (the so-called Rationalists) in the 1920s and 1930s. Predicated on the notions of space and time, Rationalist architectural theory sought connections with contemporary “temporal” arts, in particular, with cinema. I will elucidate aesthetic roots of Ladovskii’s use of cinematic montage in architecture, pointing to its ideological implications: the appearance of mass subject and its control through architectural means.

In his Tektology: Universal Organization Science (1913-1922) Russian revolutionary and cultural ideologist Aleksandr Bogdanov defined revolution as organization, the goal of which was empowering humanity to master the external world. My... more

In his Tektology: Universal Organization Science (1913-1922) Russian revolutionary and cultural ideologist Aleksandr Bogdanov defined revolution as organization, the goal of which was empowering humanity to master the external world. My presentation examines how in the 1920s Bogdanov’s ideas impacted Soviet architectural thought, in particular the theory of composition developed by Nikolai Ladovskii and his followers (so-called Rationalists). I trace the genealogy of the notion of organization as used by the Rationalists to argue that it functioned as a means of asserting modernist architecture’s revolutionary potential, a demiurgical power of creating a new—architectural—world.

I start by discussing the philosophy of empiriocriticism (developed by an Austrian Ernst Mach and promoted in Russia by Bogdanov), which the Rationalists used as the methodological foundation for their theory. Mach suggested analyzing the world as a sum of subjective sensations, claiming that in order to understand reality one had to study these sensations as its elements. Dissatisfied with the lack of practical output of empiriocrticism, Bogdanov transformed it into tektology, which was preoccupied not with analysis, but with synthesis of elements. Rationalists, too, made their architectural theory more practical: while their educational course at the VKhUTEMAS started with an analysis of the structure of spatial experience, it culminated with a synthesis of separate architectural elements into new spatial forms. Finally, I point out that it was Bogdanov’s “organization theory” that informed the Rationalist synthesis, which, elaborated as the theory of composition, became the core principle of their theory of architecture.

I start by discussing the philosophy of empiriocriticism (developed by an Austrian Ernst Mach and promoted in Russia by Bogdanov), which the Rationalists used as the methodological foundation for their theory. Mach suggested analyzing the world as a sum of subjective sensations, claiming that in order to understand reality one had to study these sensations as its elements. Dissatisfied with the lack of practical output of empiriocrticism, Bogdanov transformed it into tektology, which was preoccupied not with analysis, but with synthesis of elements. Rationalists, too, made their architectural theory more practical: while their educational course at the VKhUTEMAS started with an analysis of the structure of spatial experience, it culminated with a synthesis of separate architectural elements into new spatial forms. Finally, I point out that it was Bogdanov’s “organization theory” that informed the Rationalist synthesis, which, elaborated as the theory of composition, became the core principle of their theory of architecture.

Syllabus for "Architecture in the World of Production" seminar, IIT, Spring 2019

Syllabus for "Architecture and the Environment" seminar, IIT, Fall 2018