The ketos coins of Caria

in O. Henry / K. Konuk (ed.), KARIA ARKHAIA; la Carie, des origines à la période pré-hékatomnide (Istanbul, 2019), pp. 257-288.

…

39 pages

1 file

The authors discuss a series of archaic silver fractions with a head of a ketos left or right on the obverse and a spiral or star within a lattice frame on the reverse, weighing slightly over 2.00 g. They argue that the fractions are hektai on the Milesian standard. On the basis of findspots, and the evidence of some later coins of similar design but in larger and smaller denominations, they attribute the hektai to Halikarnassos. They are interpreted as an emergency coinage struck in 499-497 BC to finance Karian participation in the Ionian Revolt and resistance to its suppression by the Persians (Herodotos V, 117-121).

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Figures (25)

Related papers

Adalya, 2019

The ancient city of Keramos (modern Ören) is located on the north shore of the Gulf of Gökova, formerly the Gulf of Kerameikos and named after the city during antiquity. It was part of ancient Caria. Keramos has not been the scope of intensive surveys and systematic excavations yet; however, attempts have been made to assess the available evidence (epigraphic and literary sources) and archaeological remains. The coinage of the ancient city was only partially studied by Spanu. The recent projects of Historia Numorum Online has compiled its pre-Roman coins and Roman Provincial Coinage (Online) its Roman Imperial period coins much more comprehensively. The present study endeavours to compile civic coinage of the city from online and printed publications in addition to local museums of the region. Some private collections were also accessed. From these, conclusions have been derived that try to cast light onto the coinage of the ancient city. The types on the coins reveal information on the cults of the city; yet, there arise new questions regarding them. In particular, the archaising deity figures attested on the coins need to be further investigated.

19th International Congress of Classical Archaeology Cologne/Bonn (Germany), 22 – 26 May , 2018

ASAtena Suppl. VIII, 2020

In the absence of a complete corpus of Knossian coins, the aim of this work is to give a global view of the production of Knossian mint from 330 BC to 67 BC, combining the numerous studies that have been carried out on single issues or series minted in Knossos, in an attempt to give a more clear picture of the activity of the Knossian mint in the Hellenistic period.

Adalya 22, 2019

The present study deals with the first coins is- sued by Knossos and their current chronology, which cannot be based on firm evidence due to the absence of stratigraphical data to rely on. According to the current chronology, Gortyn and Phaistos were the first Cretan poleis to mint coins (ca. 450 BC), followed by Knossos (af- ter 425 BC). This dating shows a long delay as compared to the majority of Greek poleis, and this suggests reconsideration of the sub- ject. Three elements seem to be relevant to this purpose: the now ascertained participa- tion of some Cretan poleis in the north–south routes between the Peloponnese and North Africa; the epigraphical evidence suggesting the use of coinage in Crete at least at the end of the 6th century BC; and iconographical and stylistic analysis of Knossian first issues. In the light of the analysis proposed, even if it is not yet possible to assert with certainty the date of Knossos’ first issues, it is likely that Knossos began striking coins before 425 BC.

E. Paunov & S. Filipova (eds.), HPAKΛEOΥΣ ΣΩTHPOΣ ΘAΣIΩN. Studia in honorem Iliae Prokopov sexagenario ab amicis et discipulis dedicata, Veliko Turnovo 2012, 143–186., 2012

Two rare coins kept in the collection of the Social & Cultural Affairs Welfare Foundation (KIKPE), Athens, became the stimulus for other specimens to be sought and for questions to be raised, requiring further study on several levels. Danthalētai, Dentheleti, etc – the name of this minor Thracian tribe appears in several forms. The heavy bronze pieces of the Dantēlētai (head of Dionysos l. / warrior r. with curved sword and light shield, ΔΑΝΤΗΛ/ΗΤΩΝ) constitute a remarkable issue for the Thracian monetary affairs. First the variations of the ethnic name are discussed and then the iconography of the warrior (hair, sword, shield) is scrutinized, with ample literary references and correlation of archaeological parallels on occasion. Numismatic comparanda in stylistic terms are provided both for the reverse and the obverse, while the metrological data are assessed in context. The few glimpses at a known provenance lead obviously to a focal area highlighted between the northern bank of the upper course of Hebros and the Haimos mountain ridge; the role of ‘Emporion Pistiros’ (probably Adjiyska Vodenitsa, near Vetren) is also examined to an extent. All things considered, and viewed in historical perspective, a dating of this coinage in the middle of the third quarter of the 4th century BC (ca. 339–335 BC?) is thought to be quite probable. The bronze coins with the legend ΜΕΛΣΑ (filleted bucranium / fish) present an even more difficult puzzle; for starters, known and not so known pieces were traced. Discussion follows at length on the filleted bucranium and the fish while searching also for stylistic comparanda. The challenge of the strange legend (Melsa) required some necessary commentary before giving a thorough inspection at the chances for a valid interpretation. Certain options —e.g. an attribution to “a Messa of the Apolloniates” that evolved later into Anchialos— are examined and are found lacking, especially under the light of overstrike evidence (two pieces, one on AE of Philip II, the other on AE of Cassander). The latter alongside with other kinds of evidence provide a terminus post quem in or after the last fifteen years of the 4th century BC. Then argumentation is pondered on the hypothesis that the legend should correspond to an unknown so far Thracian chieftain (Melsas); this and some other possibilities towards certain civic issues are rejected. The key for deciphering this riddle seems to lie by the northern coast of the Keratios near Byzantion; close study of historical topography and other clues reveal that probably there is a connection between the site of Semystra and the ΜΕΛΣΑ coins. Several elements are taken into account, such as the filleted bucranium, etc; all in all, this may be a case of syncretism materialized in a period of dire straits, due to the Celtic presence in Thrace after 278 BC; perhaps a sanctuary in the premises of Byzantion, dedicated to the cult of a certain legendary hero Melsas, proceeded to strike a brief coin issue, possibly in association of a religious festival or an important anniversary, at a moment of temporary shortage in small change (maybe some time in the years ca. 275-250 BC). Further on the coinage in the name of Melsas see: Y. Stoyas, ‘The case of the MELSA coins: A reappraisal’, in: U. Peter & V. F. Stolba (eds), Thrace – Local Coinage and Regional Identity, Berlin 2021, 231–262.

in R. Ashton / S. Hurter (ed.), Studies in Greek Numismatics in Memory of Martin Jessop Price (London, 1998), pp. 197-223; pl. 47-50.

In conclusion, we can say that the peculiar Thasian-Thracian Union was created around and because of the rich mining zone within the southern Thracian lands. According to O. Picard, coins are the biggest testament to the large volume and importance of economic activities associated with mining operations. This slow and complex process is interconnected with coinage circulation that was self-sustaining in the mining area. Even Athens did not have the manpower and materials necessary for the establishment and development of a mine.17 Undoubtedly, Thracian rulers are those who provided Thasos, and probably Athens and other large contractors, with all the important terms and resources for a successful profitable activity in the mining area, namely political patronage, military protection, experienced ancestral miners, metal workers and coin workers, a significant amount of slaves, timber, charcoal and water. This cooperation led to the differentiation of the specific cultural and economic zone, shown by coinage circulation and the object of our study. In brief, Thasos was the motor, but the Thracian mainland was the origin and the reason for the existence of the rich small denomination silver coinage in the region of our research in the 6th–5th century BC.

Weight standard

The weight table shows that the heavier of the ketos coins, those with head facing to the right, weigh in general 2.20-2.24 g, while the overwhelming majority of those with head facing left weigh around 2.00-2.09 g. The precision and consistency of the weights of the left-facing coins is extraordinary. Nevertheless, a certain number of the unworn ketos fractions, particularly those with head facing left, weigh much less than the apparent theoretical standards of about 2.25 and 2.10 g. These tend to cluster around certain diecombinations (see, for example, cat. 22-31, 46, 48) and suggest that on occasion lighter coins were struck either by order of the authorities or because of private peculation. Kagan/Kritt 1995, p. 264, point out that the ketos coins in general are a little too heavy to conform with what might prima facie be the most attractive explanation for their standard, namely that they were hektai (sixth staters or diobols) on the Aiginetan standard, for Aiginetan sixths would weigh a theoretical 2.03 g. They suggest that they were tetrobols on the Samian standard used for class B of the "winged boar" drachms of Samos. However, the standard of about 2.25 g which the right-facing ketos coins seem to have adopted is significantly heavier than two-thirds of the weight of Samian Class B drachms, which cluster at about 3.20 g 9 . Given that the mint of the ketos coins was somewhere in the Halikarnassos area (see below), we believe that the standard came from a mint closer at hand, and that they should be regarded as slightly reduced hektai or diobols on the Milesian standard, based on a stater of about 14.10 g, which was used in the archaic period not only at Miletos, but also at Knidos, Lindos and Karpathos (as well as on the Samian Class A "winged boar" drachms). The reverses of the Milesian eighth and twelfth staters of the late 6 th -early 5 th centuries, particularly those of the eighths, are very similar to the reverses of the ketos coins (e.g. SNG Kayhan 455-460), and the immensely common Milesian twelfths have been found in or near the villages of Çiftlik and Etrim some 15 km east of Bodrum-Halikarnassos 10 . The eighths have on the obverse a lion-mask facing, and on the reverse a double or treble lattice frame The Ketos Coins of Karia enclosing a star, the whole within a square incuse. The twelfths have on the obverse a protome of a lion left or right with head reverted, and on the reverse a simpler stellar design, also in a square incuse. The star in both cases is rather different from the star on the ketos coins, for it comprises four stubby rays emanating from a central point and ending in the four corners of the design, with chevrons or floral decoration between each. Nevertheless, the overall similarity is striking.

Metal Analyses

Forty coins from the 2002 hoard were analysed in 2005 by proton activation (PAA) at the Centre Ernest-Babelon by the late Jean-Noël Barrandon. The table below gives the contents in percentages for the five main components: silver, copper, lead, gold and bismuth. Trace elements (nickel, cobalt, zinc, arsenic, rhodium, palladium, tin, antimony, tellurium, platinum and mercury) are given in ppm. Very high levels of silver fineness were achieved, with 27 coins (67.5 %) having a silver purity of at least 98 %. This is not uncommon with late archaic series which tend to have a high silver content, usually in the range of 97-99 % 11 . A noteworthy feature of the hektai silver is the low lead content even when the silver content is low (typically < 0.30 %), see diag. 1). This pattern differs greatly from the silver used for early Athenian owls which usually have a higher lead content 12 .

Archaic Athenian owls generally have a low gold content (usually < 0.06 %), which contrast with our hektai featuring a higher gold content (0.1 -0.4 %, 11 For archaic coins of Asia Minor, see e.g. the Asyut hoard coins in Gale et al. 1980, 23f.; for 8 coins of Chios, see Hardwick et al. 1998, 379; for 11 hemidrachms of Kaunos (5 th century BC) from the "Hecatomnus hoard" analysed with the same method in the same laboratory, see Konuk 2002, 115. 12 Gale et al. 1980 The Ketos Coins of Karia 2). It would thus appear that neither Laurion silver nor owls were used to strike our kete which present, however, gold/lead ratios which are quite close to those of the archaic coins of Aegina that were analysed with the Asyut hoard coins 13 . The gold/bismuth ratios of our hektai are also quite similar to those observed in Aiginetan silver coins falling within the Siphnian lead isotope field (diag. 3) 14 . The cluster formed by low gold/bismuth examples (lower left corner of the diagram) can be compared to similar Athenian coin profiles.

The possibility remains of course that the silver used for our hektai was obtained from local mines in Asia Minor, perhaps in Karia. There is one silver mine in the Halikarnassos peninsula which was exploited in the Ottoman period, located near Myndos, where the modern village is aptly named Gümüşlük ('of silver' in Turkish) 15 . Finally, when copper, lead and gold concentrations are examined, they show ternary ratios that are quite close to those found in Athenian owls of the 5 th century BC 16 .

Place of issue

We may first of all discount the ketos coins in the Mit Rahineh, Demanhur, Asyut and Jordan hoards, for they are evidence only for the well-documented circulation in Egypt and the Middle East of archaic Greek coins of many mints in and around the Aegean basin 17 . The coin in the "Sinope" hoard, an assemblage of coins from many parts of the Achaemenid empire, silver bars and jewellery, was probably regarded as a piece of bullion, and the findspot is of little relevance. The only other hoards with a known provenance are the 20 coins found at Alâkilise 18 , an ancient site on the coast about 20 km 13 Gale et al. 1980, 13, fig. 2. Early Aiginetic turtles were probably struck with silver from Siphnos, while later ones used Laurion silver, see Kraay/Emeleus 1962, 12-14;Gale et al. 1980, 35 This is not the place to enter into the debate of the origin of the metal used to strike early coins from Aegina. 14 Gale et al. 1980, 13 15 Paton/Myres 1897 Although it is probable, we have no evidence, however, that the mines were in use in ancient times. 16 Flament/Marchetti 2004, 183. 17 See, for example, Price/Waggoner 1975, 13-22. Note that cat. 70a may well also have been found in Egypt for it was donated to the British Museum by the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie. 18 CH 8, 38, followed by CH 9, 348, gives the meaningless "Kisebükü" as an alternative name for Alâkilise. This seems to derive from notes made by Martin Price concerning 6 coins said to be from the hoard which were shown to the British Museum in, we suspect, the 1980s. We believe that the coins probably belonged to the estate of G.E. Bean, who died in 1977, and that Bean recorded the east of Bodrum/Halikarnassos (perhaps Amynanda, a dependency of Syangela 19 ), and the 7+ coins said to have been found in a remote area near Bitez, about 5 km west of Bodrum 20 , near the ancient site at Gürice. Other single finds are of importance for our purposes. Bodrum Museum inv. 2827 (cat. 30 below) was bought from a dealer in Bodrum in 1968, andBodrum Museum inv. 1909 (no (i) in the list of left-facing hektai with undetermined dies at the end of the catalogue) was bought at Çiftlik some 15 km east of Bodrum. A further specimen was found inside the temple of Athena at Pedasa some 5-6 km north of Bodrum by an excavation team under Adnan Diler and in an archaeological context of the early 5 th century BC 21 . In addition, Yarkin (1975, 16), learned from locals that ketos coins had been found in the areas of Alâzeytin near Çiftlik and (some 5-6 km to the north) of Etrim, the latter being the site of Syangela 22 .

The Alâkilise hoard led Bean/Cook 1955, 95f., to suggest that the ketos coins may have been struck by Syangela, which they located at Alâzeytin, the largest Archaic site in the region of Alâkilise. In 1995, Kagan and Kritt proposed attribution to Kindye 23 on the basis of a coin of larger denomination in the ANS (see below, cat. C, 1), which has a full-length ketos right on the obverse, a simplified star of four rays within a diamond-shaped frame of dots within two lines on the reverse, and, apparently, the letters KI to the left of the frame 24 . But Kindye lies some 20-30 km north of the sites where ketos hektai were found in the areas of Alâkilise and Bodrum, and the case was undermined a few years later by the appearance of a second coin of the same denomination and types with the letters ΑΠ-ΟΛ-ΛΩ-ΝΟΣ around the frame on the reverse find-spot as Alâkilisebükü ("bay of Alâkilise"), which occurs on local maps. CH 8, 38, erroneously states that the 6 coins are in the British Museum: they seem in fact to have been dispersed on the market (see cat. 57e, 65d, 68b, A58/P?, dies not determined (viii), and dies not determined (ix)). 19 Bean/Cook 1955, 165. 20 A, 1a). These can hardly stand for other than the deity Apollo 25 . The apparent ΚΙ on the first large coin, discussed by Kagan and Kritt, could have been the initials of a magistrate such as Ki(mon) or, less likely, could have stood for Apollo's sister (Artemis) Ki(ndyas) 26 . A new coin of this larger denomination with legend ΑΛΙ-ΚΑΡ, which appeared on the market in 2017 (cat. B, 1) and clinches attribution to Halikarnassos, prompted Jonathan Kagan and Ute Wartenberg to re-examine under a powerful microscope the coin at the ΑΝS. They kindly inform us that the only letter visible under the microscope is Λ or Α (which before was read as Κ) and that the I is not a letter but part of the side of the circular incuse.

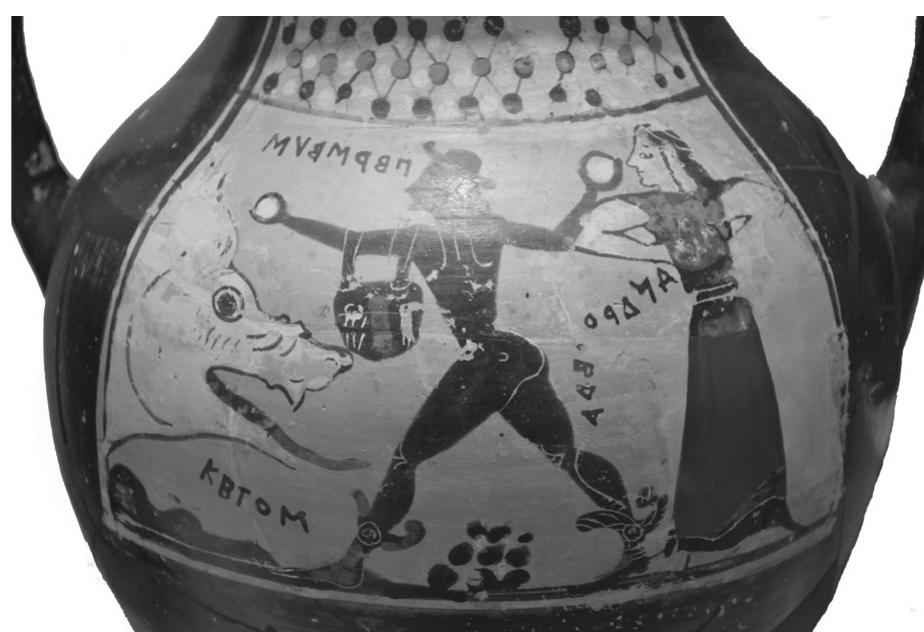

Figure 1

The punch die used to strike this and the following specimens has a break where the ΛΩ letters stood. This area has been re engraved to depict a corn ear or a leaf.

The reverse type of coins cat. Α-C differs from that of our smaller ketos hektai in that the central star has only four stubby rays and the hatching of the lattice frame is composed of dots rather than short lines, but the overall similarity of design makes it virtually certain that all four issues belong to the same mint. The letter forms on cat. A coins, particularly the omega and the splayed four-bar sigma seem to belong to about the middle of the 5 th century 27 , a half-century later than our ketos hektai. Eight previously unpublished specimens of Α-Β appeared on the market in 2017 and early 2018. Sold by the same dealer, they were part of a new unrecorded hoard. The best-preserved specimens weigh around 5.90 g and it would be reasonable to assume that a weight of ca. 6.00 g was targeted which perfectly fits a hemistater of Aiginetic standard. A switch from the Milesian standard of the hektai to the Aiginetic of the later hemistaters need occasion no surprise, given the increasing popularity of the Aiginetic standard during the first half of the 5 th century in south-west Asia Minor 28 .

25 In the published volumes of LGPN, Apollon is attested only once as a personal name, and that is very doubtful (Vol. I, s.v. -a 2 nd century AD inscription from Cyrenaica, which may however refer to an Apollonios). 26 It could be suggested that a rare issue of much later obols with an eight-rayed star on the obverse and the letters ΚΙ on the reverse (e.g. SNG von Aulock 3699) was struck at the same mint as the ketos coins, and that this was Kindye. However, von Aulock recorded that it had been bought along with several coins of Kibyra, which seems to be the more probable attribution. 27 The shape of the omega and sigma may be compared to the ones found on the perhaps slightly earlier diskoboloi staters of neighbouring Kos, see Barron 1968, 80. Kos is about 25 km distant from the coast of Halikarnassos. 28 See, for example, Sheedy 1998, with reff. A group of much smaller fractions, weighing about 0.50 g and thus probably twenty-fourths or hemiobols on the Aiginetic standard, offers further evidence for the identification of the mint of our ketos hektai. On the obverse they have a head of a ketos right, and on the reverse a star of eight rays in a square or, less frequently, round incuse: see cat. Ε-F. Stylistically they look distinctly later than our hektai and may thus be contemporary with the hemistaters of Aiginetic weight discussed above. Babelon , 1001 detected two letters below the ketos' beard on an example from the Waddington collection in the BnF, Paris, and thought he could construe them as alpha and lambda. He thus tentatively attributed the fraction to Halikarnassos, but the reading was very unclear indeed. What surely must have led him to propose that attribution is the coin's provenance: its old round ticket has the following handwritten annotation: "Trouvée à Boudroum" 29 . Another equally worn specimen (cat. E, 1b) is preserved in in the BnF and comes from the collection of de Luynes 30 . It must already have been in Parisian custody when Babelon published the Waddington coin in his Traité, but he makes no mention of it. Four further specimens which appeared on the market in the past few years had the apparently single letter Λ written horizontally beneath the beard. Finally, an example appearing on the market in 2013 has the clear legend ΑΛ, vindicating Babelon's reading and attribution. With this in mind one can now just detect a trace of the righthand hasta of an alpha below the lambda on the Waddington and de Luynes coins.

Given the provenances of the ketos hektai close to Halikarnassos, we thus attribute them, along with the later hemistaters and hemiobols, to Halikarnassos. Whatever the true etymology of the toponym, the initial syllable Hal will have suggested to Greek-speaking inhabitants a reference to the sea (ἅλς), where the ketos was at home 31 . As for the contemporary specimens with the legend "of 29 This provenance was not mentioned in Babelon's Traité and appears to be unpublished. 30 Babelon 193030 Babelon , 61, no. 2705pl. C, 2705 with an attribution to Halikarnassos following his father's Traité. 31 We owe this suggestion to Rostislav Oreshko at the Istanbul conference in 2013. Note also the full-lenght ketos depicted on a Roman period floor mosaic found in the ruins of the Salmakis fountain complex just at the west of the harbour entrance, opposite the sanctuary of Apollo, see Özet 2009;Poulsen 2015, 369-370. We thank Poul Perdersen for drawing our attention to this find.

Richard Ashton / Koray Konuk

The Ketos Coins of Karia Apollo", these may have been issued in honour of the sanctuary of Apollo at Halikarnassos which stood on the Zephyrion peninsula 32 .

Purpose of the ketos hektai

We suggest that the most likely occasion for the production of the ketos hektai would be the Ionian Revolt of 499-494 BC. In Herodotos' account, the Karians joined the revolt shortly after it broke out in 499 BC. The Persians sent an army south under Daurises to crush them. The Karians resolved on resistance at a meeting at White Pillars, but were heavily defeated in two battles at the Marsyas River and near Labraunda 33 . However, they then destroyed Daurises' army in an ambush "on the Pedasos road" 34 . After the destruction of Miletos in 494, they were of course re-conquered by the Persians. Our proposal is that the ketos coins were struck by Halikarnassos in around 499-497 BC to pay for hostilities against the Persians, whether for the procurement of equipment or the payment of soldiers. If, as we suppose, the ambush described by Herodotos took place on the road to the Pedasa which lies just 5-6 km north of Halikarnassos (rather than its namesake on Mount Grion), the close involvement of Halikarnassos would be very likely 35 . The idea that the ketos hektai constituted 32 The castle of St Peter has obliterated its remains, but a number of architectural blocks found on the site as well as inscriptions provide evidence of its existence in this location. Pieces of goodquality white marble include two speirai from column bases of Samian type, many unfluted column drums, a column neck, two Ionic capitals and a marble rooftile, see Baran 2009, 295. One inscription is a Hellenistic border stone inscription from the sanctuary which says that no one should go to the "akra" unless they have an official duty. This akra is likely to correspond to the uppermost part of the castle where the French Tower stands today, see Baran 2009, 295. Archaeological traces of cuttings on the bedrock for setting ashlar blocks have been found in that location, see Baran 2010, 108, pl. 111. A global assessment and stylistic comparisons of the architectural material suggest a date in the first half of the 5 th century BC for the construction of the temple, see Baran 2010, 112. For a general discussion on the Apollo sanctuary, see also Pedersen 1994, 27-31 andid. 2009, 331-332. Note that the earliest written evidence pertaining to the sanctuary of Apollo is the famous inscription relative to disputed property of ca. 465-450 BC (SIG 45;Tod 1933, 36-40) which orders that proceeds of sold property should be consecrated to the sanctuary of Apollo. 33 Contra Bresson (in this volume). 34 Herodotos V, 117-121. 35 We prefer the city just north of Halikarnassos, given that it would be natural for Daurises' forces to penetrate further south into Karia after their victories at the Marsyas River and near Labraunda. Bresson (in this volume) argues for the city on Mount Grion. However, Pedasians near Halikarnassos had a reputation as fierce warriors and they are described, some 40 years earlier, by an emergency war coinage is supported by the impression that they were struck intensely over a very short period. The Milesians were involved with the Karian resistance, and in particular sent a contingent to help at the disastrous battle near Labraunda; their leadership of the Ionian Revolt and close involvement with the Karians may have caused the latter to adopt the Milesian weight standard and stellar reverse type for the ketos coinage. Halikarnassos, like other Karian cities, seems to have struck very little other coinage in the late archaic period, just a few fractions featuring the forepart of Pegasos on the obverse and the forepart of a goat on the reverse. Several series can be observed and the earliest two are the heavier with weights clustering around 1.00-1.10 g (figs. 4-5) 36 ; being half the weight of our ketos hektai, they can be described as hemihekta. Later series have lower weights, around 0.70-0.75 g, an ideal weight for obols on the Attic standard. It is interesting to note that in ca. 465-450 BC, the inscription of Halikarnassos on disputed property, already mentioned above (note 33) in connection with Apollo, states that a hemihekton (the only coin denomination cited) had to be paid to each juror. The second series of Pegasos/goat hemihekta would perfectly fit the time frame of the inscription (fig. 5).

Figure 5

We may surmise that other Karian cities contributed silver for the production of the ketos hektai, but Halikarnassos itself under the Lygdamid dynasty in the late archaic period was already a city of substance, in which opulent architectural features have been observed 37 .

The date in the first half of the 490s which we propose for the ketos hektai does not conflict with their presence in the Demanhur and Mit Rahineh hoards, both dated roughly to about 500 BC, even allowing for the lapse of time between striking and burial in Egypt. The dates of the hoards are not so Herodotos (I, 175, 1) as "the only men in this region of Karia who resisted Harpagos [the commander of the Persian army in western Asia Minor], and they also gave him more trouble than all the others by fortifying a mountain called Lide". 36 Fig. 4

Figure 4

APPENDIX: A COINAGE FOR TELMESSOS MINOR ?

Before the confirmation of the legend ΑΛ on the obverse of the later ketos hemiobols and the appearance of the AΛΙ -KAΡ hemistater, we were tempted by the idea that the ketos hektai may have been issued by the Apolline divination site of Telmessos Minor, recently identified by a French team under Raymond Descat and Koray Konuk as the extensive ancient site at Alâzeytin 38 . Following Radt's suggestion 39 , the team identified the remains of an archaic temple at the site 40 , and Descat and Konuk proposed that the coins may have been struck by the sanctuary to pay for the construction or maintenance of its religious buildings, each coin perhaps representing a day's pay for an artisan 41 . The sanctuary was probably wealthy and had enjoyed ateleia from early times 42 . They suggested that the reverse type may represent the coffering of the temple's ceiling, as has been proposed for the reverse design of the late archaic tridrachms and didrachms of Delphi, another Apolline seat, 43 and/or have been derived from the reverses of the early eighths and twelfths of Miletos, which in turn may represent the coffering of the oracular temple of Apollo at Didyma. As we have seen, Milesian twelfths are found in the Çiftlik-Etrim area. By way of parallel note also that in the mid-4 th century, a small issue of hemidrachms was struck in the name of the temple of Apollo at Didyma (presumably at the mint of Miletos) with the inscription ΕΓ ΔΙΔΥΜΩΝ ΙΕΡΗ 44 . 38 Konuk 2012a, 54: "…an alternative attribution can be made to the Carian Telmessus"; Descat 2013b, 139-141; Descat/Konuk forthcoming. 39 Radt 1970, 39-42. 40 For a 3D model of the temple, see Cavalier/Mora 2011. 41 If this were so, workers at Telmessos would have received slightly more silver per day than their counterparts building the new city of Rhodes a century later, who may have received per day a Chian-weight hemidrachm of about 1.9 g (Ashton 2001, 92), but significantly less than construction and other manual workers at Athens in the 5 th and 4 th centuries (Loomis 1998, 104-20). 42 As stated in a Hellenistic inscription: JHS 14, 1894, 377. Telmessos' genos of diviners was quite famous and its reputation crossed the borders of Karia. King Croesus consulted them among others, prior to declaring war against Kyros, and Alexander the Great's principal seer was Aristander of Telmessos: see Harvey 1994. 43 Price/Waggoner 1975, 51-3, andreff. ad loc. 44 BMC Ionia, 189, nos. 1-2, pl. XXI, 8;Head, 1911, p. 585. As for the obverse type, Descat and Konuk noted that several ancient sources 45 relate that Telmessos conducted its divination business by dint of, inter alia, astrology and the interpretation of terata or ostenta i.e. wonders, prodigies, portents. They suggested that the ketos of the coins may represent a play on the word teras in its concrete sense of a monster, applied in ancient literature to, for example, monstrous serpents or serpent-like monsters. Punning types were of course common on early Greek coinage. The star-like reverse type could then refer to the practice of astrology; there was, after all, a constellation named after the ketos.

An origin for these coins at Telmessos would in part explain their strong presence in Egypt, where, although coins from Greek mints of large denomination are common, those of smaller size are less so. Karian mercenaries are frequently attested in Egypt from the 7 th to the 5 th centuries, and one might speculate that, before embarking for their service with the Pharaohs, such mercenaries routinely consulted Apollo at Telmessos about their future prospects, and acquired ketos coins during their sojourn at the sanctuary. Nevertheless, the general and well-attested closeness of contacts between Karia and Egypt is in itself a sufficient explanation, and it is worth noting that Halikarnassos was one of the founding members of the trading post at Naukratis.

One weakness in the theory that Telmessos produced the coinage to pay for a building programme is that, as we have seen, the ketos hektai seem to have been struck over a very short period, perhaps just a few weeks or months, presumably for a specific, short-term, purpose. This is not easy to reconcile with a building programme which, in the nature of things, could have lasted years, unless one adds the additional hypothesis that it was struck to cater for an emergency such as damage caused by an earthquake. No evidence for such an event has yet been discovered.

In any case, the firm evidence provided by the new coins discussed above makes an attribution to Telmessos no longer tenable. Thus, the balance of probability still strongly favours Halikarnassos as the mint for all the ketos coins. One could however speculate that, whatever the political relationship . 6) 47 . Nevertheless, it is worth adding that Halikarnassos itself in the late archaic/early classical period had an important sanctuary of Apollo (see supra, note 33), and the deity was the principle obverse type of the coinage of Mausolos and his successors; Halikarnassos probably struck its first civic series with Apollo in silver (tetradrachms and drachms of Chian weight) and bronze in ca. 400 BC.

Figure 6

Less likely would be the hypothesis that the divination site actually struck the coinage to finance Karia's involvement in the Ionian revolt with money provided from the other Karian cities and/ or from its own resources, for, unlike Telmessos, Halikarnassos is known to have had a mint, and it is more economical to suppose that the Karians used its existing facilities for their emergency coinage. 46 In the archaic period Telmessos was on the territory of Syangela, but later in the 5 th century it seems to have come under the political control of Halikarnassos: Descat/Konuk forthcoming. 47 Leake 1856, Asiatic Greece, p. 64; SNG Fitzwilliam 4718. Fig. 6. 48 The Catalogue is not intended as an exhaustive corpus. Hektai marked with an asterisk are illustrated. 49 We have placed the relatively few reverse dies with stellar design which are paired with the right-facing ketos last in that issue, on the (weak) grounds that they may represent a transition between the two issues.

The Ketos Coins of Karia

OTHER DENOMINATIONS

A. Obv. Full-length ketos to right with scaled body, forked tail, dorsal sail and pelvic fin; all within linear circle. Rev. Star pattern of four rays emanating from a central dot, within a diamond-shaped frame composed of dots within two linear borders; outside lattice frame, ΑΠ-ΟΛ-ΛΩ-ΝΟΣ; all within linear circle. Aiginetic-standard hemistaters. (2017), 333.

B. Same as above, but with the legend ΑΛΙ-ΚΑΡ.

1. A3/P3* 5.93 Roma EA35 (2017), 279.

C. Same as above, but the legend previously read as Κ-Ι now reads Α or Λ (see above). Kagan/Kritt 1995, pl. 47 no. 5 (recte 4).

The wear and possible clipping of this coin mean that it must originally have weighed well above 6.13 g, and cannot have been a hemistater of Aiginetan weight. It is conceivably a Milesian hemistater (which would weigh around 7.0 g), i.e. on the same standard as our ketos hektai.

E.

Obv. Head of ketos right; ΑΛ written vertically below the ketos' beard. Rev. Star of eight rays in square incuse. Milesian-standard hemiobols.

Richard Ashton

Richard Ashton Koray Konuk

Koray Konuk