- History and Theory of Modern Architecture, Cold War history, Socialist Globalization, Right to the city, Social Sciences and Architecture, Philosophy, and 25 moreArchitecture, Political Philosophy, Architectural History, Urbanism, Networks, Urban Design, Environmental Sustainability, Globalization, Architectural Theory, Actor Network Theory, Modern Architecture, Built Environment, British Imperial and Colonial History (1600 - ), Topology, Kuwait, Structuralism, Tropical Architecture, Modernization theory, Modernist Architecture (Architectural Modernism), Cold War and Culture, Henri Lefebvre, Cold War, Modernism, Modernism and Postmodernism In Architecture, and Hamid Dabashiedit

- Łukasz Stanek is Senior Lecturer at the Manchester School of Architecture, The University of Manchester, UK. Stanek a... moreŁukasz Stanek is Senior Lecturer at the Manchester School of Architecture, The University of Manchester, UK. Stanek authored "Henri Lefebvre on Space: Architecture, Urban Research, and the Production of Theory" (Minnesota UP, 2011) and "Architecture in Global Socialism: Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War" (Princeton UP, 2020). Stanek taught at the ETH Zurich, Harvard University GSD, and the University of Michigan. Twitter: @StanekLukaszedit

In the course of the Cold War, architects, planners, and construction companies from socialist Eastern Europe engaged in a vibrant collaboration with those in West Africa and the Middle East in order to bring modernization to the... more

In the course of the Cold War, architects, planners, and construction companies from socialist Eastern Europe engaged in a vibrant collaboration with those in West Africa and the Middle East in order to bring modernization to the developing world. Architecture in Global Socialism shows how their collaboration reshaped five cities in the Global South: Accra, Lagos, Baghdad, Abu Dhabi, and Kuwait City.

Łukasz Stanek describes how local authorities and professionals in these cities drew on Soviet prefabrication systems, Hungarian and Polish planning methods, Yugoslav and Bulgarian construction materials, Romanian and East German standard designs, and manual laborers from across Eastern Europe. He explores how the socialist development path was adapted to tropical conditions in Ghana in the 1960s, and how Eastern European architectural traditions were given new life in 1970s Nigeria. He looks at how the differences between socialist foreign trade and the emerging global construction market were exploited in the Middle East in the closing decades of the Cold War. Stanek demonstrates how these and other practices of global cooperation by socialist countries—what he calls socialist worldmaking—left their enduring mark on urban landscapes in the postcolonial world.

Featuring an extensive collection of previously unpublished images, Architecture in Global Socialism draws on original archival research on four continents and a wealth of in-depth interviews. This incisive book presents a new understanding of global urbanization and its architecture through the lens of socialist internationalism, challenging long-held notions about modernization and development in the Global South.

Łukasz Stanek describes how local authorities and professionals in these cities drew on Soviet prefabrication systems, Hungarian and Polish planning methods, Yugoslav and Bulgarian construction materials, Romanian and East German standard designs, and manual laborers from across Eastern Europe. He explores how the socialist development path was adapted to tropical conditions in Ghana in the 1960s, and how Eastern European architectural traditions were given new life in 1970s Nigeria. He looks at how the differences between socialist foreign trade and the emerging global construction market were exploited in the Middle East in the closing decades of the Cold War. Stanek demonstrates how these and other practices of global cooperation by socialist countries—what he calls socialist worldmaking—left their enduring mark on urban landscapes in the postcolonial world.

Featuring an extensive collection of previously unpublished images, Architecture in Global Socialism draws on original archival research on four continents and a wealth of in-depth interviews. This incisive book presents a new understanding of global urbanization and its architecture through the lens of socialist internationalism, challenging long-held notions about modernization and development in the Global South.

Research Interests: Middle East Studies, Middle East History, Iraqi History, Cold War and Culture, Cultural Cold War, and 15 moreHistory of West Africa, Cold War, West Africa, Ghana, Modern Architecture, Arabian Gulf, Nigeria, Cold War International Relations, Cold War history, Middle East, History and Theory of Modern Architecture, Kuwait, West African History, African Architecture, and Arab architecture

Shows how Lefebvre’s theory of space developed out of direct engagement with architecture, urbanism, and urban sociology. In this innovative work, Łukasz Stanek frames a uniquely contextual appreciation of Henri Lefebvre’s idea that space... more

Shows how Lefebvre’s theory of space developed out of direct engagement with architecture, urbanism, and urban sociology. In this innovative work, Łukasz Stanek frames a uniquely contextual appreciation of Henri Lefebvre’s idea that space is a social product. Stanek explicitly confronts both the philosophical and the empirical foundations of Lefebvre’s oeuvre, especially his direct involvement in urban development, planning, and architecture. Stanek offers a deeper and clearer understanding of Lefebvre’s thought and its implications for the present day.

This book documents the export of architecture and urban planning from socialist Poland to the Middle East and North Africa in the last decades of the Cold War, and the impact of this experience on the production of urban space in Poland... more

This book documents the export of architecture and urban planning from socialist Poland to the Middle East and North Africa in the last decades of the Cold War, and the impact of this experience on the production of urban space in Poland after socialism.

Toward an Architecture of Enjoyment, the first publication of Henri Lefebvre’s only book devoted to architecture, redefines architecture as a mode of imagination rather than a specialized process or a collection of monuments. Lefebvre... more

Toward an Architecture of Enjoyment, the first publication of Henri Lefebvre’s only book devoted to architecture, redefines architecture as a mode of imagination rather than a specialized process or a collection of monuments. Lefebvre calls for an architecture of jouissance—of pleasure or enjoyment—centered on the body and its rhythms and based on the possibilities of the senses.

This volume coins the term “Team 10 East” as a conceptual tool to discuss the work of Team 10 members and fellow travelers from state-socialist countries—such as Oskar Hansen of Poland, Charles Polónyi of Hungary, and Radovan Nikšic of... more

This volume coins the term “Team 10 East” as a conceptual tool to discuss the work of Team 10 members and fellow travelers from state-socialist countries—such as Oskar Hansen of Poland, Charles Polónyi of Hungary, and Radovan Nikšic of Yugoslavia. This new term allows the book’s contributors to approach these individuals from a comparative perspective on socialist modernism in Central and Eastern Europe and to discuss the relationship between modernism and modernization across the Iron Curtain. In so doing, Team 10 East addresses “revisionism” in state-socialist architecture and politics as well as shows how Team 10 East architects appropriated, critiqued, and developed postwar modernist architecture and functionalist urbanism both from within and beyond the confines of a Europe split by the Cold War.

When Henri Lefebvre published The Urban Revolution in 1970, he sketched a research itinerary on the emerging tendency towards planetary urbanization. Today, when this tendency has become reality, Lefebvre’s ideas on everyday life,... more

When Henri Lefebvre published The Urban Revolution in 1970, he sketched a research itinerary on the emerging tendency towards planetary urbanization. Today, when this tendency has become reality, Lefebvre’s ideas on everyday life, production of space, rhythmanalysis and the right to the city are indispensable for the understanding of urbanization processes at every scale of social practice. This volume is the first to develop Lefebvre’s concepts in social research and architecture by focusing on urban conjunctures in Barcelona, Belgrade, Berlin, Budapest, Copenhagen, Dhaka, Hong Kong, London, New Orleans, Nowa Huta, Paris, Toronto, São Paulo, Sarajevo, as well as in Mexico and Switzerland. With contributions by historians and theorists of architecture and urbanism, geographers, sociologists, political and cultural scientists, Urban Revolution Now reveals the multiplicity of processes of urbanization and the variety of their patterns and actors around the globe.

Research Interests:

This article revisits comparative urban studies produced during the Cold War in the framework of ‘socialist worldmaking’, or multiple, evolving and sometimes antagonistic practices of cooperation between socialist countries in Eastern... more

This article revisits comparative urban studies produced during the Cold War in the framework of ‘socialist worldmaking’, or multiple, evolving and sometimes antagonistic practices of cooperation between socialist countries in Eastern Europe and decolonising countries in Africa and Asia. Much like the recent ‘new comparative urbanism’, these studies extended the candidates, terms and positionalities of comparison beyond the Global North. This article focuses on operative concepts employed by Soviet, Eastern European, African and Asian scholars and professionals in economic and spatial planning across diverse locations, and shows how they were produced by means of ‘adaptive’ and ‘appropriative’ comparison. While adaptive comparison was instrumental in the application of Soviet concepts in countries embarking on the socialist development path, appropriative comparison juxtaposed concepts from various contexts – whether the ‘West’ or the ‘East’ – in order to select those best suitable for the means and needs on the ground. This article argues that this conceptual production was conditioned by the political economy of socialist worldmaking and shows how these experiences are useful for a more critical advancement of comparative urban research today.

Research Interests:

This article discusses the partial integration of companies from socialist Eastern Europe into the nascent economic globalisation in the late Cold War. By focusing on the industrial slaughterhouse designed and built in Baghdad by East... more

This article discusses the partial integration of companies from socialist Eastern Europe into the nascent economic globalisation in the late Cold War. By focusing on the industrial slaughterhouse designed and built in Baghdad by East German and Romanian companies (1974-81), it shows how they operated within and across the political economy of state socialism and the emerging, Western-dominated market of construction services. In Baghdad, East Germans and Romanians struggled with working across differing monetary regimes, inefficient corporate structures and the requirement to comply with Western standards and regulations. This article shows how they strived to bypass obstacles and to exploit opportunities stemming from their liminal and unequal position in Iraq. By zooming into architectural and engineering documentation, it argues that petrobarter agreements, or the exchange of crude oil for goods and services, shaped programmes, layouts, technologies and materialities of buildings constructed by Eastern Europeans in Iraq and the region.

Research Interests:

Recent reports on Chinese and Russian involvement in infrastructural developments in Africa and the Middle East coined the phrase “New Cold War”. Yet when seen from the Global South, the continuities with the 20th century lie less in the... more

Recent reports on Chinese and Russian involvement in infrastructural developments in Africa and the Middle East coined the phrase “New Cold War”. Yet when seen from the Global South, the continuities with the 20th century lie less in the confrontation with the West, and more in reviving the collaboration between the “Second” and the “Third” worlds. In my recent book Architecture in Global Socialism (Princeton University Press, 2020) I argue that architecture is a privileged lens to study multiple instances of such collaboration, and their institutional, technological, and personal continuities.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests: Architecture, Globalization, Cold War and Culture, Cultural Cold War, Cold War, and 9 moreArt and Aesthetics of the Cold War, Cold War history, History of architecture, History and Theory of Modern Architecture, African Architecture, Arab architecture, Architecture and Globalization, Socialist Architecture, and Architecture Design Cold War and Culture

In 1967 the state planning office Miastoprojekt Krakow from socialist Poland delivered the master plan of Baghdad which, together with its amendment that followed in 1973, provided the legal framework for the development of the Iraqi... more

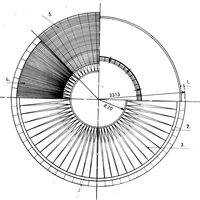

In 1967 the state planning office Miastoprojekt Krakow from socialist Poland delivered the master plan of Baghdad which, together with its amendment that followed in 1973, provided the legal framework for the development of the Iraqi capital during the oil-boom era. With the 1973 plan about to be replaced by a new one, a graduate seminar Mapping Baghdad 1956-2016 at the Manchester School of Architecture looked back at the fifty years of history of Miastoprojekt’s plans for Baghdad, their guiding ideas, and their impact on the development of the city. In collaboration with scholars from Baghdad University and the Institut français du Proche-Orient, we have used Geographic Information System (GIS) with archival planning documents and maps collected during my long-term research project about the flows of architectural expertise between socialist countries in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and West Africa in the cold war. The following article documents this experience of working with GIS systems with heterogeneous and ambiguous data; and shares some findings of the seminar. In particular, GIS-based research allowed us to clarify the planning approach that informed the master plans; to identify the extent to which they guided the development of housing, green spaces, transportation systems, and heritage preservation in Baghdad from the 1960s to the 1980s; and to speculate about their effects on architectural culture in Iraq.

Paper available at: http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/26558/the-master-plans-of-baghdad_notes-on-gis-based-span

Paper available at: http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/26558/the-master-plans-of-baghdad_notes-on-gis-based-span

Research Interests: Digital Humanities, Middle East Studies, Iraqi History, Urban Planning, Modernist Architecture (Architectural Modernism), and 12 moreModernism, Middle East Politics, Urban And Regional Planning, History of Planning, 19-20th Century (Architecture history), Digital mapping, History of Architecture and Town Planning, History of Urban Planning, Gis in History, Cold War and the Middle East, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and Iraqi Architecture

Architects from Socialist Countries in Ghana (1957–67): Modern Architecture and Mondialisation discusses the architectural production of the Ghana National Construction Corporation (GNCC), a state agency responsible for building and... more

Architects from Socialist Countries in Ghana (1957–67): Modern Architecture and Mondialisation discusses the architectural production of the Ghana National Construction Corporation (GNCC), a state agency responsible for building and infrastructure programs during Ghana’s first decade of independence. Łukasz Stanek reviews the work of GNCC architects within the networks that intersected in 1960s Accra, including competing networks of global cooperation: U.S.-based economic institutions, the British Commonwealth, technical assistance from socialist countries, support programs from the United Nations, and collaboration within the Non-Aligned Movement. His analysis of labor conditions within the GNCC reveals a negotiation between Cold War antagonisms and a shared culture of modern architecture that was instrumental in the reorganization of the everyday within categories of postindependence modernization. Drawing on previously unexplored materials from archives in Ghana, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, the United Kingdom, and the United States, the article reveals the role of architects from European socialist countries in the urbanization of West Africa and their contribution to modern architecture’s becoming a worldwide phenomenon.

Research Interests: African Studies, Globalization, Postcolonial Studies, Cold War and Culture, African History, and 28 moreHistory of West Africa, Cold War, West Africa, Yugoslavia, Modernist Architecture (Architectural Modernism), Ghana, Globalisation and Development, Postcolonial Theory, Modern Architecture, Henri Lefebvre, Postcolonial theory (Cultural Theory), Tropical Architecture, East German History, Nkrumah, Polish Art and Architecture, Cultural Globalization, East Germany, Soviet Design and Architecture, Accra, Croatian Architecture, Constantinos Doxiadis, Socialist Architecture, Yugoslav Architecture, History of Soviet Architecture, Alternative Globalization, GDR Architecture, East German Architecture, and Planetary urbanization

This article discusses the contribution of professionals from socialist countries to architecture and urban planning in Kuwait in the final two decades of the Cold War. In so doing, it historicizes the accelerating circulation of labour,... more

This article discusses the contribution of professionals from socialist countries to architecture and urban planning in Kuwait in the final two decades of the Cold War. In so doing, it historicizes the accelerating circulation of labour, building materials, discourses, images, and affects facilitated by world-wide, regional and local networks. By focusing on a group of Polish architects, this article shows how their work in Kuwait in the 1970s and 1980s responded to the disenchantment with architecture and urbanization processes of the preceding two decades, felt as much in the Gulf as in socialist Poland. In Kuwait, this disenchantment was expressed by a turn towards images, ways of use, and patterns of movement referring to ‘traditional’ urbanism, reinforced by Western debates in postmodernism and often at odds with the social realities of Kuwaiti urbanization. Rather than considering this shift as an architectural ‘mediation’ between (global) technology and (local) culture, this article shows how it was facilitated by re-contextualized expert systems, such as construction technologies or Computer Aided Design software (CAD), and also by the specific portable ‘profile’ of experts from socialist countries. By showing the multilateral knowledge flows of the period between Eastern Europe and the Gulf, this article challenges diffusionist notions of architecture’s globalization as ‘Westernization’ and reconceptualizes the genealogy of architectural practices as these became world-wide.

Research Interests:

ABE Journal 6 (2014), introduction to the theme issue of ABE Journal 6 (2014), edited by Ł. Stanek

This special supplement is an exhibition on magazine’s pages and presents a selection of projects and realized buildings by Polish architects, planners, and engineers working in Africa and the Middle East during socialist Poland (People’s... more

This special supplement is an exhibition on magazine’s pages and presents a selection of projects and realized buildings by Polish architects, planners, and engineers working in Africa and the Middle East during socialist Poland (People’s Republic of Poland, PRL). The majority of the presented material was shown at the exhibition PRL™ Export Architecture and Urbanism from Socialist Poland held as a part of the festival “Warsaw under Construction” (October 15–November 15, 2010, Warsaw Museum of Modern Art/ Museum of Technology).

When in 1962 Miastoprojekt-Krako´w won the international tender for the master plan of Baghdad, this initiated two decades of intense engagement in Iraq of this architectural and planning office from the People’s Republic of Poland. By... more

When in 1962 Miastoprojekt-Krako´w won the international tender for the master plan of Baghdad, this initiated two decades of intense engagement in Iraq of this architectural and planning office from the People’s Republic of Poland. By choosing an office from a socialist country, Iraqi governments from Abdul Karim Kassem to Saddam Hussein not only responded to the specific geopolitical conditions of the Cold War in the Middle East, but also aimed at drawing on the Polish experience of post-war reconstruction, with the state taking an active role in the processes of urbanisation. The lessons learned from the reconstruction ofWarsaw and the construction of new towns such as Nowa Huta, designed by Miastoprojekt, reverberated throughout its two master plans for Baghdad (1967, 1973). Its numerous projects in Iraq focused on the distribution of welfare (housing and education) on a territorial scale and included, in particular, the General Housing Programme (1976–1980). The attempt to mediate between the ambitions of modernisation and attention to local specificity required extensive research. This study links the increasing role of research in the Iraqi projects of Miastoprojekt both to its previous contributions to architectural culture in Poland and to the political economy of architectural labour in the Cold War.

Research Interests:

From the catalogue of the exhibition "Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980" at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, 15 July 2018 - 13 January 2019.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Architects, planners, and construction firms from socialist Eastern Europe shaped the urbanization of West Africa and the Middle East during the Cold War in ways we had not, until now, considered. Łukasz Stanek examines the strategic... more

Architects, planners, and construction firms from socialist Eastern Europe shaped the urbanization of West Africa and the Middle East during the Cold War in ways we had not, until now, considered. Łukasz Stanek examines the strategic ambitions and sometimes contradictory motivations behind this global cooperation: https://thinkbelt.org/shows/interstitial/architecture-in-global-socialism-lukasz-stanek

Research Interests:

This interview by Hilde Heynen and Sebastiaan Loosen engages with Łukasz Stanek in a conversation that contextualizes the Special Collection in Architectural Histories on Marxism and architectural theory across the East-West divide. It... more

This interview by Hilde Heynen and Sebastiaan Loosen engages with Łukasz Stanek in a conversation that contextualizes the Special Collection in Architectural Histories on Marxism and architectural theory across the East-West divide. It follows Stanek’s keynote lecture for the conference Theory’s History 196X–199X: Challenges in the Historiography of Architectural Knowledge (Brussels, February 8–10, 2017) and his recent book, Architecture in Global Socialism: Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War (2019).

Research Interests:

Łukasz Stanek talks to Tribune about his book on how architects and planners in Eastern Europe designed and built towns and cities across the world between the 1950s and 1980s.

Research Interests:

Against the dominant reduction of architecture’s globalisation to “Westernization,” this talk argues that the world-wide mobility of architecture was accelerated after World War II by competing visions of global cooperation. Among the... more

Against the dominant reduction of architecture’s globalisation to “Westernization,” this talk argues that the world-wide mobility of architecture was accelerated after World War II by competing visions of global cooperation. Among the most consequential of such visions was that of the world socialist system, launched by the Soviet Union as an alternative to the Western-dominated “globalism” of the 1970s and to the splits among socialist countries in the previous decade. Rather than a utopia or an ideology, in this talk I will discuss the world socialist system as a set of specific instruments of foreign trade which regulated the circulation of design and construction practices between socialist Europe and countries in Africa and Asia. By focusing on Iraq between the coup of Qasim (1958) and the end of the first Gulf war (1991), I will show how such instruments of the world socialist system as employment contracts, currency exchange rates, and barter agreements offered opportunities and constraints for architects, planners and construction companies from socialist countries. These instruments circumscribed the conditions of labour of actors from Eastern Europe and the conditions of collaboration with their Iraqi partners which, in turn, facilitated specific design methodologies and the techno-politics of buildings designed and constructed in Iraq. This argument will be made by revisiting the master plans of Baghdad delivered by a Polish office (1967, 1973); housing neighbourhoods by Romanian contractors; infrastructure in Iraqi cities by Bulgarian, East German and Soviet design institutes; public buildings by Yugoslav firms; and teaching curricula at the Department of Architecture in Baghdad to which architects from Czechoslovakia contributed. Since the results of these engagements have continued to impact the conditions of urbanization in Iraq until today, this talk is not an archaeology of failed attempts at architecture’s globalization, but rather an alternative genealogy of these processes.

Research Interests: Cold War and Culture, Urban Planning, Cold War, Architectural History, Islamic' Architecture, and 14 moreArchitectural Theory, Modern Architecture, Vernacular Architecture of Middle East, Cold War Science and Technology, Urban And Regional Planning, Cold War International Relations, Polish Art and Architecture, History of Baghdad, Islamic art and architecture, Middle-East urban deisgn and planning, GDR Architecture, East German Architecture, Iraqi Architecture, and Romanian Architecture

The "Introduction to Traditional Nigerian Architecture" was considered by its author, the Polish architect and architectural historian Zbigniew Dmochowski, to be a contribution to the nation-building process in post-independence Nigeria... more

The "Introduction to Traditional Nigerian Architecture" was considered by its author, the Polish architect and architectural historian Zbigniew Dmochowski, to be a contribution to the nation-building process in post-independence Nigeria and a starting point for a “modern school of Nigerian architecture”. Published posthumously in London in 1990, this three-volume book resulted from a comprehensive survey Dmochowski carried out in Nigeria, first as an employee of the colonial Department of Antiquities in the 1950s, and later as the head of the Institute for Tropical Architectural Research at the Gdańsk Polytechnic (1965-82). As an “expert” from socialist Poland traveling to West Africa during the Cold War, the work of Dmochowski was legitimized both by Polish state-led urbanization after the Second World War, and by a longer tradition of architectural engagement into nation-building processes in Central Europe. The latter reverberated in his survey of Nigeria’s architecture which appropriated and developed drawing and mapping techniques that he had employed in his 1930s surveys of traditional wooden buildings in eastern Poland. This specific tradition of drawing, resulting in Dmochowski’s synthetic axonometries, contrasted with the drawings of the British, late colonial “tropical architecture” in West Africa, which privileged the analytical section. By focusing on the production process of Dmochowski’s axonometries, this paper will argue that this difference reflected a distinct project of Nigerian architectural culture which came to the fore in the designs of national museums to which he contributed at the colonial Department of Antiquities, and developed after independence by his collaborators, both Nigerian and Polish (museums in Benin, Esie, and Kaduna).

Research Interests:

This talk discusses the architectural production of the Ghana National Construction Corporation (GNCC) responsible for building and infrastructure programs of postcolonial Ghana during its first decade of independence (1957-67). The work... more

This talk discusses the architectural production of the Ghana National Construction Corporation (GNCC) responsible for building and infrastructure programs of postcolonial Ghana during its first decade of independence (1957-67). The work of GNCC architects is reviewed as assembling resources from various networks, from local ones to competing networks of global cooperation which intersected in 1960s Accra: American-based economic institutions, the British Commonwealth, socialist technical assistance, and the Non-Aligned Movement. The analysis of labor conditions within the GNCC reveals a negotiation between Cold War antagonisms and a shared culture of modern architecture which was instrumental in the redistribution of everyday times and places according to categories of postcolonial modernization. Drawing on previously unexplored materials from archives in Ghana, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, the UK and the US, this paper reveals the understudied role of architects from socialist countries in the urbanization of West Africa, and their contribution to modern architecture becoming world-wide.

Research Interests:

This paper discusses the impact of architects, planners and construction companies from socialist countries on Baghdad’s urban development from the 1960s to the 1980s. Filling in the gap in the architectural historiography of Iraq, this... more

This paper discusses the impact of architects, planners and construction companies from socialist countries on Baghdad’s urban development from the 1960s to the 1980s. Filling in the gap in the architectural historiography of Iraq, this paper will clarify the conditions of possibility of major planning and architectural projects in Baghdad between Qasim’s coup d’état (1958) and the first Gulf War under Saddam Hussein (1991). The discussion of both state companies and individual architects from Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union will show how their entrance conditions to Iraq resulted in specific professional opportunities and constraints. Operating within networks of the Eastern Block and the Non Aligned Movement, these actors exploited the Cold War dynamics in the Middle East and profited from the differences between state socialist economies and the emerging global market of architectural and construction services. While architects from both sides of the Iron Curtain working in Bagdad since the Second World War shared the postulate of adapting modernism to local conditions, the focus on their professional trajectories offers a more differentiated account on their labor of “adaptation”.

Research Interests:

Team 10 East never existed. In difference to the short-lived CIAM-Ost, the first generation of Central European architects was impaired in terms of exchanges with the West and might have been reluctant to assume a unified identity which... more

Team 10 East never existed. In difference to the short-lived CIAM-Ost, the first generation of Central European architects was impaired in terms of exchanges with the West and might have been reluctant to assume a unified identity which would seemingly confirm the division of the continent imposed by the Iron Curtain. Yet what was shared by the members of the Team 10 from the region, such as Oskar Hansen from Poland and Charles Polónyi from Hungary, and the followers from Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, was not only their hindered mobility, but also their affiliation with Central European architecture culture and the experience of architecture practice in state socialism. This talk launches the research project Team 10 East which focuses on the contributions of architects from socialist Europe to the discourse of the Team 10, and their specific reading of questions of modernization, consumption, community, and everyday life. Among these questions, that of the state was particularly relevant, and the projects of Oskar Hansen were exercises in radical reformism, requiring and envisaging the (socialist) state as both powerful and self-limiting agent of the processes of urbanization. Rather than being a retroactive manifesto, Team 10 East revisits the work of Hansen and others according to their conditions and aspirations, aiming at an account that is more historically founded and more speculative.

Research Interests:

Review article of Katherine Lebow’s Unfinished Utopia: Nowa Huta, Stalinism, and Polish Society, 1949-56 (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2013).