Pompeii

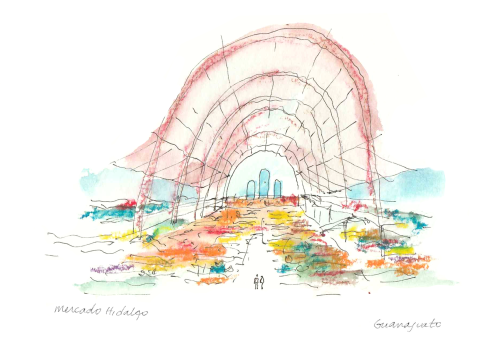

Few moments of my life have taught me more about architecture than the time I was thrown out of the House of Menander in Pompeii.

I did it for my mother. She was a Latin teacher back in Greensboro, North Carolina, who loved everything Roman. The House of Menander was one of the finest houses in ancient Pompeii before a volcano destroyed it in 79 AD.

So there I was in 1967 AD, an architecture student standing before a restored Pompeian house named for a Greek playwright on a scorching day in July only to find that the building I’d come over 4000 miles to see was closed.

That’s when I noticed a gate with a broken latch. I pushed it.

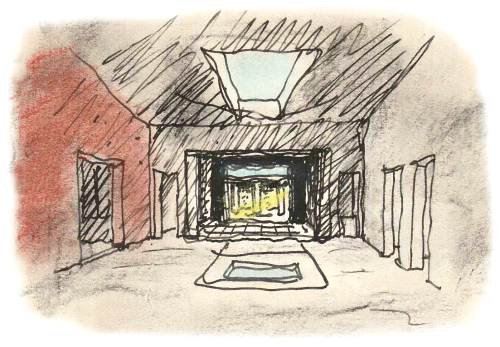

Once inside I found a house arranged around two courtyards: one was in shadow, the other opened to the sky. You travelled from dark to light, as Le Corbusier said, from minor to major key. It was like moving from a forest into a clearing, a revelation, like hope.

I thought of this recently when I watched our new president and vice president emerge from a dark tunnel into the light of the National Mall in Washington for their inauguration.

The police that day in Pompeii were not amused. “Dio mio,” they said when I showed them my sketch. “Un architetto!” I didn’t mention my mom.