Julius Caesar and Sliced Apples

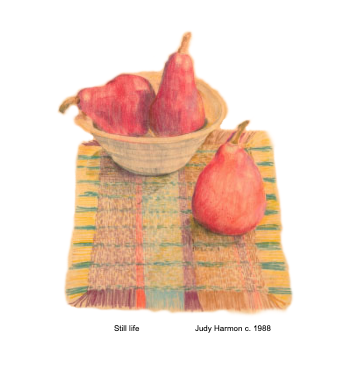

To put it plainly, my mother didn’t know how to cut an apple. She’d hold the fruit in her left hand and cut slices with the knife toward her. She would ease the blade through the apple’s flesh and stop just short of her thumb.

“Don’t ever cut the knife towards you,” my father admonished. At the age of six, how could I determine which parent was right?

Virginia Donaldson could sew a blouse and weave a basket as fine as a hummingbird’s nest. Her fingers could knit and purl as smoothly as they could play Chopin or stroke her son’s hair.

She could also bend her thumbs backwards 90 degrees. She pointed out that Julius Caesar had the same kind of thumbs. After her cats and her children, my mother loved Julius Caesar the best. And dexterity, she said, comes from the Latin “dexter,” meaning right hand – skillful.

I resisted Latin, but I learned to build balsa airplanes with an X-Acto knife.

Twenty years later, when I was standing near the Curia of Pompey in Rome where Julius Caesar strolled to his assassination, my mind drifted to the tart scent of freshly sliced apples.

It’s possible to imagine that Julius Caesar and my mom are together now, comparing double-jointed thumbs while she cuts a red Rome apple.

I still cut apples the way I saw her do it.