Insomnia and its Charms

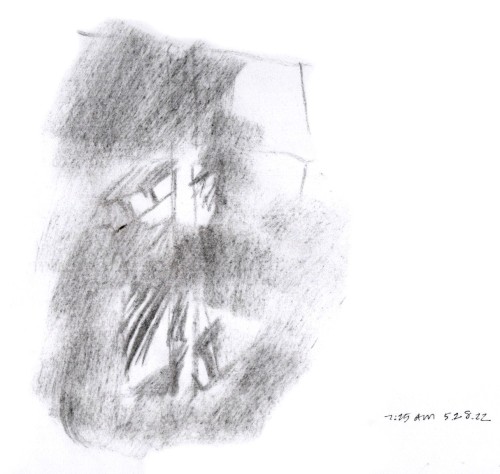

A katydid sings in an oak tree near the street. Jupiter is an orange disk in the sky. It’s 3 a.m. and I’m sitting outside in the garden. Just me and my insomnia.

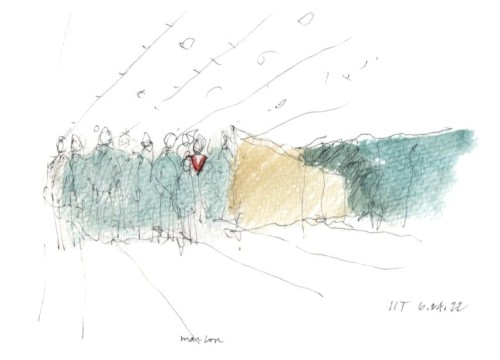

Sleep, wrote the Bard, is the “…balm of hurt minds, great nature’s second course…” In fact, during Shakespeare’s time it was normal to wake after midnight. Back then folks got out of bed, put another log on the fire, folded the laundry, talked. Then they slept until dawn. We have the industrial revolution to thank for insomnia. With the eight-hour or more workday, we’re trapped in an eight-hour sleep cycle. If we wake, we worry. Politics, marriage, did I put the cheese away?

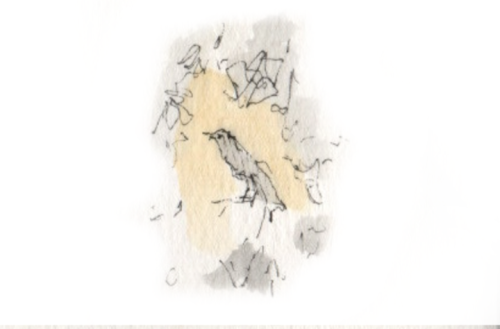

Sitting out at 3 a.m., I don’t fret about the cares of the day. I’m listening to the katydid which sings at 65 beats per minute, the same as my heart.

Remembering Macbeth’s lament, “Sleep that knits up the raveled sleave of care…,” I may fold the laundry in a little while.