Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Dr Yuliya Velykoredko, Dermatology Resident, and Dr Michal Bohdanowicz, Dermatology Resident, University of Toronto, Canada. DermNet New Zealand Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy editors: Gus Mitchell/Maria McGivern. September 2017.

Introduction Function Innate immune response Complement system Adaptive immune response

The skin has an immune system that protects the body from infection, cancer, toxins, and attempts to prevent autoimmunity, in addition to being a physical barrier against the external environment.

The skin immune system is sometimes called skin-associated lymphoid tissue (SALT), which includes peripheral lymphoid organs like the spleen and the lymph nodes.

Skin anatomy and cellular effectors

Immune sentinel cells

Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers.

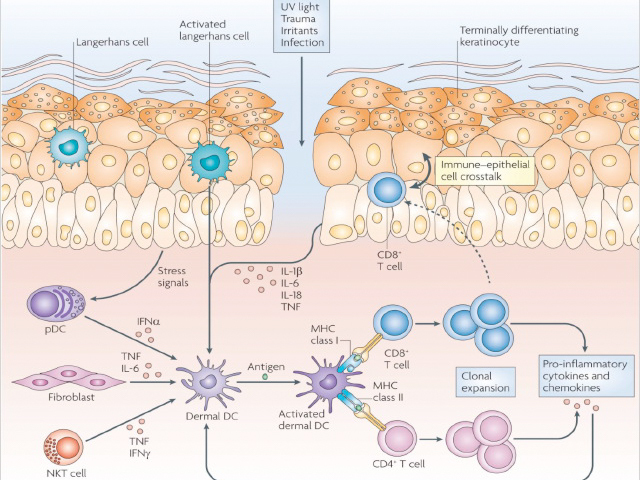

The immune system of the skin has elements of both the innate (nonspecific) and adaptive (specific) immune systems. Immune cells inhabit the epidermis and dermis.

The key immune cells in the epidermis are:

The dermis has blood and lymph vessels and numerous immune cells, including:

There is continuous trafficking of immune cells between the skin, draining lymph nodes, and blood circulation. The skin microbiome also contributes to the homeostasis of the skin immune system.

The innate immune response is immediate and is not dependent on previous immunological memory.

Keratinocytes are the predominant cells in the epidermis. They act as the first line of innate immune defence against infection. They express Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which are pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect conserved molecules on pathogens and trigger an inflammatory response.

Keratinocytes communicate with the rest of the immune system through:

Macrophages are phagocytic cells that can discriminate between the body's cells (self) and foreign molecules. After phagocytosis by macrophages, an invading pathogen is killed inside the cell. Activated macrophages recruit neutrophils to enter the circulation and travel to sites of infection or inflammation.

Neutrophils are the first cells to respond to infection. They directly attack microorganisms by phagocytosis and by degranulation of toxic substances.

Epidermal and dermal dendritic cells are involved in both the innate and adaptive immune responses. During the innate response:

NK cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes that can eliminate virally infected cells and cancer cells without antigen presentation or priming.

NK cells are activated by interferons or other cytokines released from macrophages. NK cells express inhibitor receptors that recognise MHC–I and prevent undesirable attacks on self. They can kill target cells through the perforin-granzyme pathway, which induces apoptosis (programmed cell death).

Mast cells are activated in response to allergic reactions and produce cytoplasmic granules filled with pre-formed inflammatory mediators, such as histamine. They release these granules when their high-affinity immunoglobulin E (IgE) receptor (FcεRI) on the mast cell surface reacts upon contact with stimuli such as allergens, venoms, IgE antibodies, and medications.

These mediators can result in pruritic weals due to increased vascular permeability (urticaria). In rare cases, mast cell activation can lead to anaphylaxis, characterised by bronchoconstriction, dizziness, and syncope.

Eosinophils enter the skin in pathological conditions such as parasitic infestations and atopic dermatitis. Eosinophils are attracted to immunoglobulins such as IgE that are bound to complement proteins on the surface of large organisms such as helminths.

The eosinophils release cytoplasmic cytotoxic granules to kill the parasite (an innate immune response) and promote Th2 helper T cell differentiation upon release (an adaptive immune response).

The complement system is an enzymatic cascade of over 20 different proteins normally found in the blood. When an infection is present, the system is sequentially activated leading to events that help destroy the invading organism.

The complement system can also attract neutrophils to the site of infection.

The adaptive immune response is specific to a pathogen and takes a longer time to elicit. Adaptive immunity requires the production of specific T lymphocytes to identify an antigen with precision and B cells to produce specific antibodies that bind to the microbe in a 'lock-and-key' fashion.

Dendritic cells (Langerhans cells and macrophages), or antigen–presenting cells (APCs), identify antigens and present them to immature T cells. Epidermal Langerhans cells use their dendrites (arm-like projections) to survey the environment, especially in the stratum corneum. The Langerhans cells bind pathogens to their TLRs, travel to draining lymph nodes, and present antigens to naïve lymphocytes. Antigen presentation requires internalisation of the pathogen, processing inside the cell, and display of a short peptide on the surface of the APC on a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule.

There are two major types of MHC: MHC-I and MHC-II.

The skin contains resident T cells and recruits circulating T cells. T cells are unable to recognise pathogens directly. The receptor on the surface of a T cell binds to the peptide/MHC complex on the surface of the APC. Effective antigen presentation allows for naïve T cells to mature into effector T cells, which in turn differentiate into two varieties: cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T helper (Th) cells.

Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells recognise and bind to MHC-I molecules. They bind to the Fas death receptor, a protein on the cell membrane surface that initiates the perforin–granzyme pathway and cytokine-mediated pathways to induce apoptosis, which directly kills virally infected cells or tumour cells.

CD4+ Th cells recognise and bind to MHC-II molecules. They activate B cells to produce specific antibodies. Upon re-exposure to the same antigen, memory T cells can respond quickly by division and clonal expansion.

Th cells include the Th1, Th2, Th17 and Th22 subtypes. Each subtype is associated with specific signalling cytokines and effector functions.

Th1 cells produce a cell-mediated immune response to kill intracellular pathogens.

Th2 cell activation leads to B cell stimulation and antibody production.

Th17 cells produce IL-17 and IL-22 and play a role in protection from bacterial infections and fungal infections. Th22 cells produce IL-22 and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which induces inflammation. Both Th17 and Th22 cells play a role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Other T cell populations, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), fine-tune the immune response by controlling immune cells response to foreign and self-antigens and prevent autoimmunity reactions.

B cells are responsible for creating a memory of prior antigen exposure to ensure a faster immune response and a lasting immunity. B cells produce antibodies (immunoglobulins) that can bind to specific antigens. Antibody effector functions are:

To produce antibodies, B cells require cytokine signalling and stimulatory signals from Th cells. This takes place in secondary lymphoid organs such as lymph nodes.

Upon re-exposure to the same antigen and follicular dendritic cells, B cells are activated to produce specific antibodies. This process allows for the generation of memory B cells and long-lived plasma cells for long-lasting immunity from infection.