A round six o’clock on a Tuesday evening, fire-alarm dispatcher Marlind Haxhialiu overheard a call come into the 911 dispatch in Brooklyn where he was stationed. Another dispatcher was asking the caller, a young boy from the sound of it, what address the child was calling from. “We don’t know,” said the voice on the other end of the line. “We’re like … we’re stuck in the sewers.” It became clear that five children, ages 11 and 12, were lost underground somewhere near the Staten Island Zoo, and though the dispatcher was trying to narrow down their location, he wasn’t having much luck. “The kids kept yelling ‘We’re stuck in a sewer,’” Haxhialiu says. “And being kids, you know, they’re being vague.”

Haxhialiu happened to have grown up in Staten Island, not far from the West Brighton neighborhood where the zoo is located. The area is mostly residential, and it is bordered by Clove Lakes Park, where about 200 protected acres of thickly forested hills and trails wrap around a chain of lakes. The park is an important ecological site full of warblers and great blue herons. It is also a location with a tendency toward flooding, surrounded by steep hills and large storm drains like the one he suspected the children had entered.

Cover Story

Within the first 30 seconds of listening, Haxhialiu quickly put in an approximate address so that the rescue teams could start moving. Then he took over the call, putting his local knowledge to use. He began asking the children a series of questions in order to home in on where they had entered the sewer system, but the information he received was contradictory — the boys said they had entered near the zoo, then from inside the park. He has three kids of his own, and as he questioned the boys in the sewer, he tried to be firm but nice at the same time, remembering that he was speaking to children. “You’re taught to be stern with some callers,” he tells me. “Just try to get their attention and get the information because time is crucial. But also, you know, you don’t want to be indifferent to their feelings.”

He tried in his mind to see the area as he remembered it from his own explorations as a child. “I knew exactly where they’d been,” Haxhialiu says. “Growing up, I’d sneak through the zoo and stuff like that. I had an idea where they would be, where the entrance was, even though, back in the day, those areas were kind of closed off.” He continued to ask questions, trying to figure out where they had started, how long they had been crawling inside the sewer, whether they had turned right or left once inside — knowing that as long as they were responsive on the phone, they were not gravely injured or unconscious.

Haxhialiu had worked on complex rescues of all kinds — he had been a key participant in the rescue seven years earlier of a British tourist who had boarded an inflatable raft in Newark in the hope of making it all the way to Manhattan. After a collective effort identifying the man’s position within the open water of the harbor, he had been located and pulled out near the Statue of Liberty. As the rescue teams rushed to the area, he hoped that the children’s location underground would be easy to pinpoint and that the cell-phone signal that was allowing them to communicate with rescuers would hold.

Larger than Manhattan but with the smallest population of all five boroughs, Staten Island contains forgotten stretches of land that would be unlikely to linger where the use of space is fanatically optimized. Packs of wild turkeys roam suburban streets and parking lots; white-tailed deer swim across the narrow channel that separates New York from New Jersey. Not far from the island’s southern tip, there’s a “boat graveyard” where people dump old ships. This past August, a worker at a container terminal discovered a fox carrying a human leg in its mouth. All of which is to say it is a natural place to get lost.

As the dispatchers conducted a high-stakes game of 20 questions, engines carrying officers specially trained in confined-space rescues were barreling toward the intersection of Martling Avenue and Clove Road. In addition to handling the bread and butter of fire departments everywhere (fires), the FDNY is prepared for “all hazards”: everything from building collapse to swift-water extraction.

“New York City is a big city,” says FDNY chief John Hodgens. “We have every type of area that we would need to respond to, such as subways, buildings, on-the-river tunnels, construction sites. Just so many places where things can potentially go wrong.” Most confined-space rescues involve industrial structures or construction sites, places where gases can build up and special equipment is needed to protect against environmental hazards. “A few times a year, people get entangled in machinery,” Hodgens tells me. “Sometimes they get trapped inside oil tankers or chemical tanks. People fall in as they construct them.” But a sewer rescue, Hodgens says, is rare — and it was even rarer for children to be the ones lost in a hazardous confined space.

As the units neared the park, Lieutenant John Drew of Rescue 5 knew that he and the rest of the team were bound to encounter unforeseen difficulties. “Most of the time when we train, it’s a Disney World scenario — there’s really no true hazards,” Drew says. But in real-world emergencies like this one, he adds, “I’m sending my men into the unknown.” Communicating with dispatch on the radio and drawing on his driver’s knowledge of the area, Drew & Co. arrived at the location where they guessed that the children had entered — and saw the open mouth of the tunnel littered with five sets of backpacks and jackets. “It was pretty much like a scene out of a movie,” Drew says.

Drew learned that the children had been crawling for some 15 minutes through the sewer system, 40 feet below street level — they had scrambled up closer to a manhole cover to get a cell-phone signal. But nobody on the surface knew how far they could have gotten within that time. The fact that they had the children on the phone and were actively speaking with them throughout the rescue was comforting, but air within a sewer is always changing and their situation could have turned at any time.

Confined-space rescues always carry risks, though sewers have dangers that are uniquely their own: oxygen deficiency, hydrogen sulfide — a rotten-smelling toxic gas generated by anaerobic processes within sewer slime — and any other hazardous material that may have been dumped by careless people. Other difficulties, like downward slopes within a pipe that could cause children or even rescuers to slip and fall, could only be guessed at. The rescue team deployed specialized metering devices that tested for oxygen deficiency and other hazardous conditions and began removing manhole covers in the area one by one as the dispatcher on the other end of the children’s 911 call told them to make noise. “I want all you guys to scream,” says the voice of the dispatcher on the call recording. “Call for help, guys. They hear you, call for help.”

As the main rescue team entered the sewer, following the path the children had taken, firefighter John Loennecker was helping open manholes nearby. When he heard the faint calls of the children below him, he jumped into action, lowering a light down through the hole. “Can you see the light?” he asked. When they answered that they could, he knew he’d have to go into the sewer. Fitted with a mask linked to a secondary air supply in case he encountered toxic gases or a low-oxygen area, as well as a rope system so firefighters could pull him out if necessary, Loennecker made his way through the muck-covered pipes. As he crawled toward them and they crawled toward him, he called out, asking if anyone was injured. They said there was one boy with injuries. Finally, he saw all five of them by the light of a single cell phone — 1,300 feet from the place where they had entered nearly an hour earlier — and led them out of the sewer system.

Only 32 minutes after the initial call, the five children were rescued, one with knees raw from crawling on the hard concrete. They told reporters that they had been playing in the area when one of the boys entered the sewer and got disoriented, so they all went in after him. They went deeper into the tunnel and couldn’t find their way out. That’s when they called for help. Now that they were back above-ground, the boys were rattled but okay — and very nervous about getting grounded.

In the end, all five boys were taken to the hospital, and no significant injuries were found. “From my perspective, everything went really well,” says Chief Hodgens. “We responded, we figured out an unusual situation, we had to think outside the box about how we would try to locate the children, and while we’re doing that, dispatch is on the line gaining information and relaying that directly to us. So it was a really coordinated operation.” Haxhialiu, the fire-alarm dispatcher, recommends that individuals who get lost look for landmarks that they can communicate to the 911 operator on the other end of the line and listen carefully to what the dispatcher is asking. “I understand when people are panicked, you’re trying to put out as much information as possible,” he says. “But that information is no good to us. The information we ask for is needed. And yelling and screaming is not going to help.”

In an interview with a local news station, Kevin Reyes, one of the five kids rescued that day, described the inside of the sewer system as dark, full of spiders, and “really tight.” “We were scared that we would not get out because our legs were numb,” he told the reporter. In the end, Kevin was, in fact, grounded by his mother, who described her feelings as frantic and then relieved. When asked by the reporter what he learned from this whole experience, Kevin’s answer was simple. “Not to go back,” he said. “Not to go in sewers.” At Clove Lakes Park, at least, there’s one sewer that’s now much harder to explore: The entrance to the tunnel where the boys got lost has been blocked off, secured, and covered in chain-link fencing.

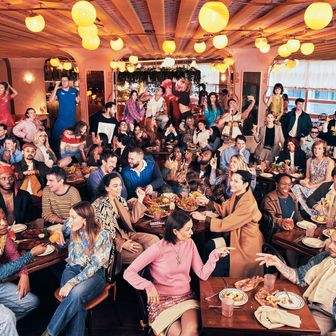

More reasons to love new york

- A $45 Million Effort to Make Pregnancy Less Deadly in Brooklyn

- Reasons to Love New York Right Now

- We Took New York’s TikTokers to Lunch