Buildings and Health

What is Health?

Health, as defined by World Health Organization in its 1948 constitution,1 is “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. This definition of health has been expanded in recent years to include (1) resilience and the ability to cope with health problems and (2) the capacity to return to an equilibrium state after health challenges.2,3

These three health domains - physical, psychological, and social - are not mutually exclusive but rather interact to create a sense of health that changes over time and place. The challenge for building design and operations is to identify cost-effective ways to eliminate health risks while also providing positive physical, psychological, and social supports as well as coping resources.

How Buildings Can Support Health and Well-being

Physical Health includes the proper functioning of internal and external body parts (e.g., organs, tissues, cells), the ability to resist disease, and the physical fitness necessary to perform daily functions without restrictions.4,5

Psychological Well-Being is a positive mental state that allows people to realize their full potential, cope with the stresses of life, work productively, and make meaningful contributions to their communities.6 It also includes resilience, happiness, high levels of satisfaction with life, and a feeling of belonging and sense of purpose.7,8,9

Social Well-Being is the extent to which a person feels a sense of belonging, acceptance, and social inclusion including participation in community activities. Positive social well-being includes having mutually beneficial friendships and social supports.

Buildings and Health Components

- Building Design

- Interior

Stress and the Physical Environment

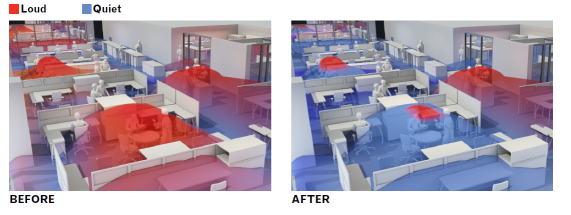

Health must also address how people adapt successfully and manage themselves in the face of physical, mental or social challenges or stressors. These challenges range from macro-level threats such as those associated with extreme weather events (resilience)9 or socioeconomic factors to micro-level threats linked to the physical environment - such as acoustic challenges, ergonomic discomforts, or material pathogens. These stressors may be encountered at home, en route to and from work, within the workplace, in settings away from home when traveling, in social and community spaces, and more. The ability to recover from these stressors relies on access to spaces and tools for recovery.10,11 Specifically, this page addresses the physical spaces and ambient conditions that can support positive health and wellness outcomes through building and site design, maintenance, and operation. Supporting personal adaptation through choice and behavioral encouragement, provision of personal control of workspaces, and access to a variety of social, psychological and physical supports enables building inhabitants to actively manage stressors to promote well-being.

Systems Thinking and the Community At Large

Current design for health and wellness includes a larger view of design that not only focuses on the individual building or space and its occupants - but requires the evaluation of benefits to the community at large. For example, identifying the connection to available parks and biking opportunities in the overall community assists with the design of building entry locations, storage facilities at point of service, staff areas to accommodate cyclists, and operationally providing a graphic cyclist map that encourages engagement for the buildings users and visitors. The integration of design with operations and training provides a stronger well-being integration than either might achieve in isolation.

Integrative Design

The goal is to promote healthy habits through good design and provide operational support and communication that potentially furthers positive behaviors by building occupants. This is achieved through the utilization of an Integrative Design Process - a process that includes the active participation of a multidisciplinary group of stakeholders relevant to a specific project from project conceptualization through operations. The group extends beyond the design team and includes operational staff, users, and administrative staff.

Site Selection and Construction

Site Selection

Selecting a building site is one of the most important decisions in designing a building, as the wrong choice could result in negative health and environmental impacts and substantial economic loss.

The Sustainable Sites ![]() Initiative provides guidelines that apply to any landscape and outlines clear objectives to meet in selecting and designing building sites. Two goals of the initiative include: Elevating the value of landscapes by outlining the economic, environmental and human well-being benefits of sustainable sites, and connecting building and landscapes to contribute to environmental and community health.

Initiative provides guidelines that apply to any landscape and outlines clear objectives to meet in selecting and designing building sites. Two goals of the initiative include: Elevating the value of landscapes by outlining the economic, environmental and human well-being benefits of sustainable sites, and connecting building and landscapes to contribute to environmental and community health.

The Partnership for Sustainable Communities![]() outlines a series of “livability principles” with several relating to the selection of a building site and ways to protect the environment. Some of the strategies include providing more reliable, safe, and economic transportation choices, promoting public health, improving total air quality, access to nature, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and investing in the creation of healthy, safe, walkable communities.

outlines a series of “livability principles” with several relating to the selection of a building site and ways to protect the environment. Some of the strategies include providing more reliable, safe, and economic transportation choices, promoting public health, improving total air quality, access to nature, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and investing in the creation of healthy, safe, walkable communities.

Site considerations might include:

For information on overall site sustainability, see the Sustainable Sites page.

Construction

There are several precautions a contractor can take during construction to protect existing and future occupant health. Construction activities used to create a space can have a significant impact on indoor environmental quality. Construction activities and close out, including inspections and anintegrated team approach to hand off to the operations team, can also greatly impact future building and occupant performance. More information on indoor air quality guidelines can be found in the ASHRAE Indoor Air Quality Guide ![]() .

.

Many construction activities create airborne contaminants that can compromise the health of occupants of the space. Much of the debris created on a construction site is “dust” related to the cutting of materials such as drywall, metal, and plaster. Introducing these particulates into the air can compromise respiratory, cardiovascular, optical, and immune health.

In addition, proper care must be taken during construction to ensure the safety and well-being of construction workers, building occupants, and visitors. Measures may include fall prevention, personal protective gear (hard hats, safety glasses, reflective vests, enclosed footwear, gloves, etc.) being required in active construction areas, and temporary barriers around dangerous equipment.

Financial Benefits

There is increasing evidence that making workplaces more conducive to occupant health and well-being can yield significant financial benefits to both employers and employees. These benefits can include minimizing absenteeism and presenteeism, lowering health care costs, and improving individual and organizational performance.

The research in this field has not advanced to the point that quantitative return on investment (ROI) calculations can be made as easily as is the case with, say, energy-efficient technologies. Making such calculations requires comparing the amount of investment required to establish healthier built environments with the returns or savings from such investments. The costs of healthier workplaces vary widely with the broad array of strategies discussed here - although many of the most effective strategies (e.g., making stairways more attractive and accessible) tend to be low cost.

Savings from healthier workplaces within the federal building portfolio could be substantial, considering that the federal government employs about 2.2 million civilian workers, on which it spends $215 billion (FY2016) on compensation, including pay and benefits.15 Through the Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) program, the government pays an average of 70% of the cost of health insurance premiums. The Federal employee absenteeism rate due to illness or injury is 2.6%.16 These large numbers indicate that even small percentage improvements in employee health, through health-focused interventions, can have dramatic effects.

Research to date has identified a wide variety of measurable benefits associated with healthier workplaces including:

Benefits of improved indoor air quality: One review and analysis of existing studies estimated that the US could save $1-4 billion by reducing absenteeism and illness associated with asthma and allergies from unhealthy building conditions, and $10-20 billion by reducing absenteeism and illness associated with sick building syndrome, among other potential savings.17 Ventilation above standard levels in particular has been associated with health and performance gains. Recent studies have found the health benefits of enhanced ventilation to exceed the per occupant costs of implementing them;18 they have also identified increases of worker cognitive performance of 61-101% under conditions of enhanced ventilation.19

Benefits of daylighting/circadian stimulation: A GSA project on circadian light found that office workers who received the most circadian stimulation at work, during the daytime, slept on average 30 minutes longer at night.20 A 2016 RAND study on sleep estimated that the US loses an equivalent of about 1.23 million working days per year due to sleep loss, translating to an economic cost of $9.9 million/year.21 These data could support a business case for investing in circadian effective light in daytime work environments.

Benefits of workplace wellness programs: The American Institute for Preventive Medicine estimated, based on numerous studies, that every dollar companies spent on worksite wellness programs returned around $3.48 due to reduced medical costs and $5.82 due to reduced absenteeism.22

Benefits of overall healthy building programs: Several case studies documenting the benefits of healthy building programs have shown promising results. The American Society of Interior Designers (ASID) found it was on track to recoup its investment in the redesign of its leased office space to meet WELL Building Standard Platinum levels within one year.23 Skanska UK, achieving BREEAM Outstanding level in an office renovation with improved daylighting, thermal comfort and IAQ, saved $36,000 in personnel costs, and reduced the payback period of an office move from 11 to 8 years by achieving 3.5 fewer building-related sick days.24

Considering all of the above, what we can say with confidence about the ROI of healthier buildings is that:

- employees represent an enormous investment;

- health and well-being can impact their performance; and

- workplace conditions can negatively or positively affect employees’ physical and mental conditions.

Therefore, investments in healthier workplaces can pay off handsomely even if precise calculations of this payback remain elusive.

Operations and Maintenance (O&M)

IAQ Policy

The development of an Indoor Air Quality policy is part of establishing and maintaining healthy indoor environmental quality. During any construction, vehicle idling and large equipment use can burn fossil fuels, increasing irritant levels and creating negative health impact in the air. Pollutant emissions may also be created from construction machinery use.

Cycle Renovations

Providing health and well-being criteria to facility management and operational teams creates an opportunity for renovations and scheduled maintenance (cycle renovations) to be programmed and planned utilizing an additional lens of supporting occupant well-being. When completing cycle renovations, complete a conditions assessment process and checklist to evaluate the following areas of the applicable project scope:

Occupant Engagement

Health & Safety Committee

Executive Order 12196 (Occupational Safety and Health Programs for Federal Employees![]() ) directs agencies to operate occupational safety and health programs to improve workplace safety and reduce employee injury or illness. This includes the development of health and safety committees (CFR 1960.36) to open and maintain communication channels between employees and their leadership to improve workplace conditions. These committees, now standard in federal agencies, model practical options for other public institutions and private companies, including those that look at opportunities beyond the basics of hazard prevention. Organizations with a higher percentage of employees actively engaged in these programs report lower rates of workplace incidents.

) directs agencies to operate occupational safety and health programs to improve workplace safety and reduce employee injury or illness. This includes the development of health and safety committees (CFR 1960.36) to open and maintain communication channels between employees and their leadership to improve workplace conditions. These committees, now standard in federal agencies, model practical options for other public institutions and private companies, including those that look at opportunities beyond the basics of hazard prevention. Organizations with a higher percentage of employees actively engaged in these programs report lower rates of workplace incidents.

Though less obvious than heavy industry settings, the typical office workplace setting has its own set of hazards, and in 2016 alone, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 3.2 incidents or illnesses occurred out of every 100 full-time workers in the office/administration industries.26 The top office injuries typically reported include falls, employees struck or caught by an object, ergonomics injuries, and vision problems.27 Health and Safety programs are an effective strategy to reduce injuries and illness in any industry.

There are a number or resources available for organizations on starting and maintaining an effective health and safety program and encouraging employees to become engaged, active participants and safety practitioners. Health and safety programs should include these basic elements:

- Safety and Health Surveys or some reporting mechanism to document workplace inspections, identification, and correction of unsafe or unhealthy workplace conditions.

- Safety and Health Committees should be open to all employees. See OSHA’s 3-part series on creating and maintaining an effective Health and Safety Committee: part 1

, part 2

, part 2 , part 3

, part 3 .

. - Mechanism for accident/incident investigation and reporting

- Continual occupational safety and health training for all employees

A safe and healthy workplace is not just achieved by preventing accidents and injury, but by also encouraging and empowering employees to take control of their personal health and well-being. Building design, operation, leadership support, and organizational culture all play key roles in employee health, well-being, and performance.

Health Promotion and Campaign Programs

Establishing employee wellness programs that promote personal health can reduce absenteeism, improve work performance,28 lower health care costs, reduce workers’ compensation and disability-related expenses, reduce workplace injuries, and improve employee morale and loyalty.29 The workplace is an integral part of a health and wellness program; effective workplaces that reflect an organization’s culture around health and well-being improve and increase employee engagement, quality teamwork interactions, and empower employees to make decisions that support personal health and well-being. In using the workplace to promote personal health and well-being, does your workspace:

- Encourage activity and collaboration?

- Provide workplace choice inclusive of all occupants' work styles, individuality, project needs, and personality traits?

- Include areas that rejuvenate and restore occupants to stay focused through the workday when accomplishing tasks/workload?

- Inspire employees want to work there?

- Include access to healthy food options?

- Provide ease of access to clean drinking water?

Health promotion campaigns are an effective way to demonstrate an organization’s commitment to health and well-being and they provide opportunities for direct engagement with occupants. Effective health promotion campaign keeps occupants empowered, engaged, and incentivized to participate.

Health Enhancing Workplace Policies

Establish policies, operations and communications that align with Health Promotion Programs and Campaigns, and active design upgrades to the built environment to glean the best outcomes.

Additional Resources

- GSA.gov | Wellbuilt for Wellbeing

- OPM.gov | Work-Life

- See Federal Occupational Health (FOH)

resources including onsite health promotion programming, virtual fitness calsses, nurtition and health coaching, and a wellnesss portal.

resources including onsite health promotion programming, virtual fitness calsses, nurtition and health coaching, and a wellnesss portal.

Personal Control, Choice, and Workplace Customization

Today, many employees have the option to work in a variety of locations. Individuals can incorporate aspects of workplace health and well-being recommendations on their own at the workplace, at home, or at “third-party places” such as coffee shops, hotels, and airports.

View home office tip sheets from GSA's Workplace 2030:

- Promote Health, Comfort, and Performance While Working From Home

- Solid Waste Management in the Home Office

- Improving Energy Efficiency of the Home Office

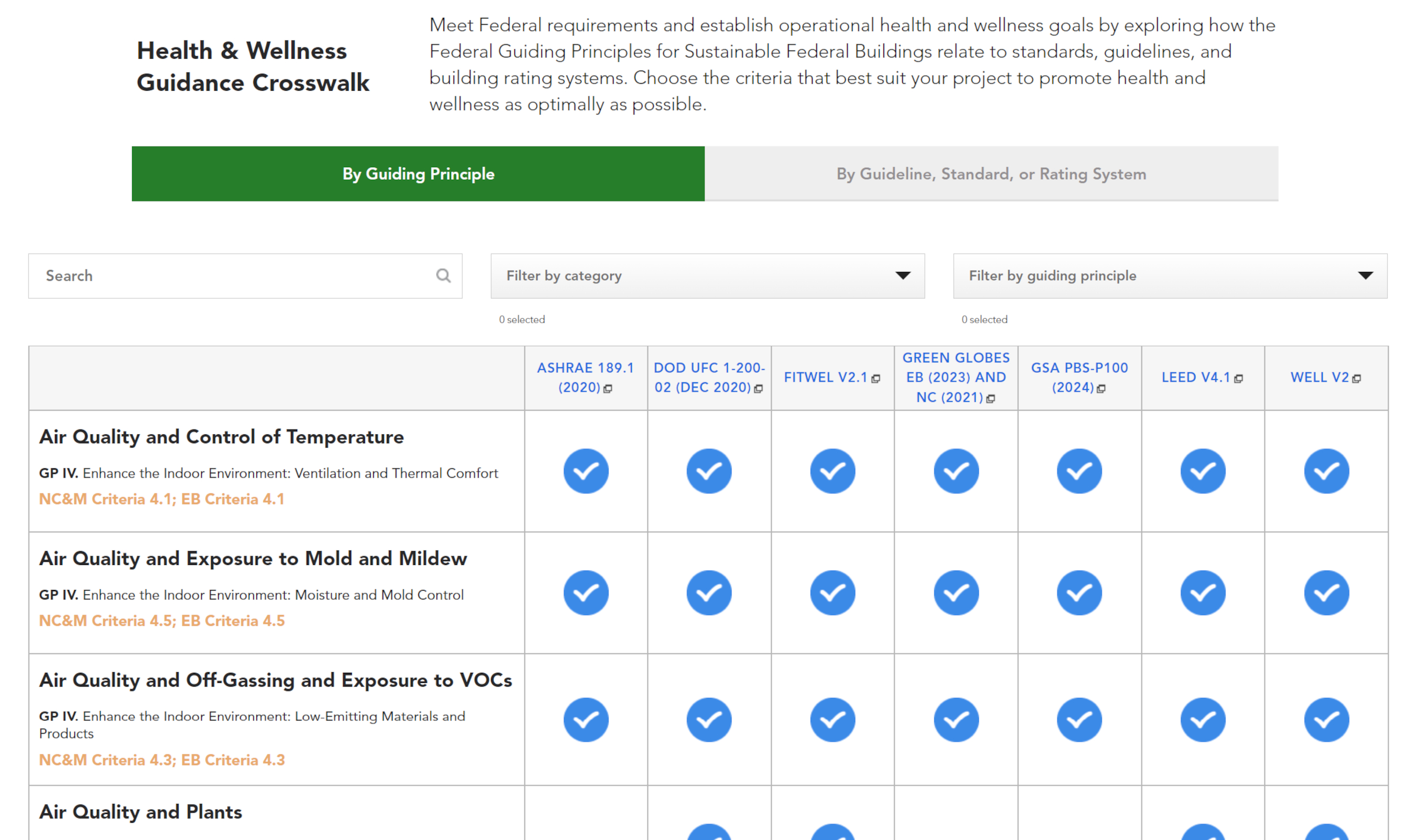

Health & Wellness Standards and Rating Systems

Resources

- Home office tip sheets from GSA's Workplace 2030:

- GSA.gov | Wellbuilt for Wellbeing

- SFTool | Total Workplace Resources

- ForHealth.org | 9 Foundations for Health (Harvard)

- Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute | Lighting Research Center

- Transamerica Center for Health Studies | "From Evidence to Practice: Workplace Wellness the Works” (2015)

- Harvard | The truth behind standing desks

- Creasy, S., R.J. Rogers, T.D. Byard, R.J. Kowalsky, and J.M. Jakicic. 2016. Energy Expenditure During Acute Periods of Sitting, Standing, and Walking

. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 13(6): 573-8.

. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 13(6): 573-8. - WBDG.org | Universal Design and Health

- AIA.org | Health

- Fitwel rating system

- WELL Building Standard

- Perkins+Will | Precautionary List

- University of California, Berkeley | Center for the Built Environment (CBE)

- Carnegie Mellon University | Center for Building Performance and Diagnostics (CBPD)

Case Studies

- ASID | ASID HQ Office Research: Pre-/Post-Occupancy Analysis

- The Importance of Daylight

- Center for Active Design

(features additional case studies, including Fitwel certified projects)

(features additional case studies, including Fitwel certified projects) - The International WELL Building Institute

- GSA Occupant Comfort Case Study

- GSA Office of Civil Rights Health Case Study

1 World Health Organization | Constitution

Related Topics

Biophilia

Biophilia addresses the human attraction to and desire to be in environments that have natural features including parks, gardens, street trees, bird feeders, flowers, big sky, and water elements. Decades of research show that affiliation with nature, whether outside or indoors, can enhance our physical, social and emotional health and boost performance.

Read more about Biophilia and Biophilic Design.

Circadian light

Circadian rhythms are biological processes that are generated and regulated by a biological clock located in the brain. These biological processes include body temperature, digestion, release of certain hormones, and a person’s wake/sleep cycle. In the absence of external cues, circadian rhythms in humans will run with a period close to, but not exactly 24 hours (in humans, circadian rhythms cycle every 24.2 hours without exposure to light). If a person does not receive enough light, their circadian rhythms become desynchronized with the local day-night cycle.

Learn more about Circadian Light.

Construction Air Quality Management

Construction activities can threaten the indoor air quality of an occupied space. Precautions should be taken to protect the health of construction workers as well as the health of occupants. These precautions include ensuring that airborne particles from construction activities are isolated from the permanently installed HVAC equipment; flushing out toxins before occupancy; ensuring absorptive materials are kept dry and that the facility is kept free from mold; and using construction materials low in harmful VOCs.

ASHRAE.org | Indoor Air Quality Guide![]()

Daylight Sufficiency Goal

The daylight sufficiency goal specifies the amount of daylight needed to provide adequate light to perform typical tasks appropriate to each space, without additional electric lighting. It is measured in lumens or foot-candles.

Find more from GSA's Saving Energy through Lighting and Daylighting Strategies![]() resource.

resource.

Daylighting

Daylighting uses natural daylight as a substitute for electrical lighting. While it will likely be counterproductive to eliminate electrical lighting completely, the best proven strategy is to employ layers of light - using daylight for basic ambient light levels while providing occupants with additional lighting options to meet their needs.

An effective daylighting strategy appropriately illuminates the building space without subjecting occupants to glare or major variations in light levels, which can impact comfort and productivity.

In order to provide equitable access to daylight ensure the space is optimized to disperse daylight well. Locate private offices toward the core of the space and specify low workstation panels. Use glass walls and light-colored surfaces on walls and desks to disperse daylight throughout the space. In all daylighting strategies, it is important to consider glare and to take steps to minimize it. Find more strategies below:

GSA | Saving Energy through Lighting and Daylighting Strategies![]()

DOE LBL | Tips for Daylighting with Windows![]()

Ergonomics

Ergonomic workspaces are designed to facilitate work while minimizing stress and strain on the body. They also accommodate user preferences and comfort. They include height-adjustable desks that can be easily moved around on casters, fully adjustable chairs, monitor arms, keyboard trays, footrests and document holders. It is important to train employees on how to adjust their workspaces to maximize comfort and health.

Flexible Workplace Design

Today’s workplaces are often in flux. Organizations change direction or develop new services. People move to new spaces and take on new responsibilities. Teams form and re-form. The spaces themselves are transformed to meet these new needs. These changes are much easier to accommodate, when the workplace design supports flexibility.

Glare Control

Glare can had an adverse affect on worker comfort and productivity. Glare control strategies block, control, or filter sunlight to avoid negative effects of glare and heat and maximize good daylight.

Healthy Buildings

Health, as defined by World Health Organization in its 1948 constitution, is “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. This definition of health has been expanded in recent years to include (1) resilience and the ability to cope with health problems and (2) the capacity to return to an equilibrium state after health challenges.

These three health domains - physical, psychological, and social - are not mutually exclusive but rather interact to create a sense of health that changes over time and place. The challenge for building design and operations is to identify cost-effective ways to eliminate health risks while also providing positive physical, psychological, and social supports as well as coping resources.

Learn more about Buildings and Health.

Indoor Air Quality (IAQ)

Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) refers to the state of the air within a space. A space with good indoor air quality is one that is low in toxins, contaminants and odors. Good air quality possible when spaces are well ventilated (with outside air) and protected from pollutants brought into the space or by pollutants off-gassed within the space. Strategies used to create good IAQ include bringing in 100% outside air, maintaining appropriate exhaust systems, complying with ASHRAE Standard 62.1, utilizing high efficiency MERV filters in the heating ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system, installing walk-off mats at entryways, prohibiting smoking with the space and near operable windows and air intakes, providing indoor plants, and using only low-emitting / non-toxic materials and green housekeeping products.

Low VOC

VOCs (volatile organic compounds) are toxins found within products (paints, adhesives, cleaners, carpets, particle board, etc) and that are released into a space’s indoor air, thus harming its quality. Low VOC products are those that meet or exceed various standards for low-emitting materials. Low-emitting standards include Green Seal, SCAQMD, CRI Green Label Plus, Floor Score, etc.

Whole Building Design Guide | Evaluating and Selecting Green Products![]()

California South Coast Air Quality Management District![]()

Occupant Comfort

Workspaces should be designed and operated to support the functional and environmental needs of occupants. Design for thermal comfort should be based on ASHRAE Standard 55. Design for air quality should be based on ASHRAE 62. Occupant comfort should be assessed frequently once a building is occupied, using ASHRAE’s Performance Measurement Protocols for Commercial Buildings.

ASHRAE.org | Standards 62.1 and 62.2![]()

Occupant Control

Workspaces should be designed to allow for occupant control over lighting (light switches, occupant or daylight sensors with override capability, etc) and thermal comfort (operable windows, individual thermostats, and underfloor air diffusers). Building operators should provide information about control use to occupants.

Occupant Engagement

Occupant engagement involves communicating with, enabling and empowering building occupants to help meet sustainability goals for the building. This can involve providing information on actions occupants can take to improve building performance and resource efficiency, while making it easy and appealing for occupants to do so (e.g. actions that improve productivity).

Occupant Satisfaction

A primary goal of sustainable design is to maximize occupant comforst and satisfaction, while minimizing environmental impact and costs. Comforst and satisfaction are important for many reasons, not least of which is that they correlate positively with personal and team performance. The greater the satisfaction, the higher the productivity and creativity of an organization. It has also been demonstrated that occupant satisfaction impacts staff rentention.

Thermal Comfort

Workspaces should be designed to provide the optimum level of thermal comfort for the occupants. Occupant comfort should be based on ASHRAE Standard 55.

ASHRAE.org | Standards 62.1 and 62.2![]()

Ventilation

Ventilation is the process of "changing" or replacing air in any space to control temperature; remove moisture, odors, smoke, heat, dust, airborne bacteria, and carbon dioxide; and to replenish oxygen. Ventilation includes both the exchange of air to the outside as well as circulation of air within the building. It is one of the most important factors for maintaining acceptable indoor air quality in buildings.

Views (to the Outside)

Building occupants with access to outside views have an increased sense of well-being. Keeping employees happy and healthy is good for business, as happy employees show higher productivity and increased job satisfaction, resulting in less employee turnover. In order to provide equitable access to views, it is recommended that private offices are located toward the core of the space and that low workstation panels are installed to allow for maximum daylight penetration. Use glass walls and partitions to enable views out from interior spaces.

Volatile Organic Compound (VOC)

Carbon compounds that participate in atmospheric photochemical reactions (excluding carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, carbonic acid, metallic carbides and carbonates, and ammonium carbonate). The compounds become a gas at normal room temperatures and degrade indoor air quality. VOCs can be found in paints, coatings, adhesives, sealants and other finish materials.

Worker Productivity

Productivity is the quality and/or quantity of goods or services produced by a worker. Good indoor environmental quality – access to views, comfortable temperatures, comfortable lighting, good acoustics, and ergonomic design, etc. – supports employees’ ability to do a good job. On the other hand, compromised IEQ hinders their ability to work. It makes good business sense, then, to keep employees happy, healthy, and productive. This, in turn, creates more and higher quality output for organizations.