kottke.org posts about journalism

My favorite presentation at XOXO this year was Ed Yong’s talk about the pandemic, journalism, his work over the past four years, and the personal toll that all those things took on him. I just watched the entire thing again, riveted the whole time.

Hearing how thoughtfully & compassionately he approached his work during the pandemic was really inspirational: “My pillars are empathy, curiosity, and kindness — and much else flows from that.” And his defense of journalism, especially journalism as “a caretaking profession”:

For people who feel lost and alone, we get to say through our work: you are not. For people who feel like society has abandoned them and their lives do not matter, we get to say: actually, they fucking do. We are one of the only professions that can do that through our work and that can do that at scale — a scale commensurate with many of the crises that we face.

Then, it was hard to hear about how his work “completely broke” him. To say that Yong’s experience mirrored my own is, according to the mild PTSD I’m experiencing as I consider everything he related in that video, an understatement. We covered the pandemic in different ways, but like Yong, I was completely consumed by it. I read hundreds(/thousands?) of stories, papers, and posts a week for more than a year, wrote hundreds of posts, and posted hundreds of links, trying to make sense of what was happening so that, hopefully, I could help others do the same. The sense of purpose and duty I felt to my readers — and to reality — was intense, to the point of overwhelm.

Like Yong, I eventually had to step back, taking a seven-month sabbatical in 2022. I didn’t talk about the pandemic at all in that post, but in retrospect, it was the catalyst for my break. Unlike Yong, I am back at it: hopefully more aware of my limits, running like it’s an ultramarathon rather than a sprint, trying to keep my empathy for others in the right frame so I can share their stories effectively without losing myself.1

I didn’t get a chance to meet Yong in person at XOXO, so: Ed, thank you so much for all of your marvelous work and amazing talk and for setting an example of how to do compassionate, important work without compromising your values. (And I love seeing your bird photos pop up on Bluesky.)

Rebecca Solnit writes about how the mainstream political press is failing the American public they claim to serve.

These critics are responding to how the behemoths of the industry seem intent on bending the facts to fit their frameworks and agendas. In pursuit of clickbait content centered on conflicts and personalities, they follow each other into informational stampedes and confirmation bubbles.

They pursue the appearance of fairness and balance by treating the true and the false, the normal and the outrageous, as equally valid and by normalizing Republicans, especially Donald Trump, whose gibberish gets translated into English and whose past crimes and present-day lies and threats get glossed over. They neglect, again and again, important stories with real consequences. This is not entirely new — in a scathing analysis of 2016 election coverage, the Columbia Journalism Review noted that “in just six days, The New York Times ran as many cover stories about Hillary Clinton’s emails as they did about all policy issues combined in the 69 days leading up to the election” — but it’s gotten worse, and a lot of insiders have gotten sick of it.

It’s really disheartening and maddening to witness how the press has failed to meet this important moment in history.

See also Jamelle Bouie’s NY Times piece this morning, straining against the normalizing currents at his own publication to actually call out Trump’s “incoherence” and “gibberish” and parse out what he’s actually trying to tell us about his plans for a second term:

Trump, in his usual, deranged way, is elaborating on one of the key promises of his campaign: retribution against his political enemies. Elect Trump in November, and he will try to use the power of the federal government to threaten, harass and even arrest his opponents. If his promise to deport more than 20 million people from the United State is his policy for rooting out supposedly “foreign” enemies in the body politic, then this promise to prosecute his opponents is his corresponding plan to handle the nation’s domestic foes, as he sees them. Or, as he said last year in New Hampshire, “We pledge to you that we will root out the communists, Marxists, fascists and the radical left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country.”

From Heather Cox Richardson, writing on the night of the debate, a reminder of just how bad Trump’s performance was, a shambolic spectacle that was met with shrugs because that’s what we expect of him:

In contrast, Trump came out strong but faded and became less coherent over time. His entire performance was either lies or rambling non-sequiturs. He lied so incessantly throughout the evening that it took CNN fact-checker Daniel Dale almost three minutes, speaking quickly, to get through the list.

Trump said that some Democratic states allow people to execute babies after they’re born and that every legal scholar wanted Roe v. Wade overturned — both fantastical lies. He said that the deficit is at its highest level ever and that the U.S. trade deficit is at its highest ever: both of those things happened during his administration. He lied that there were no terrorist attacks during his presidency; there were many. He said that Biden wants to quadruple people’s taxes — this is “pure fiction,” according to Dale — and lied that his tax cuts paid for themselves; they have, in fact, added trillions of dollars to the national debt.

Richardson also quotes Monique Pressley’s debate night tweet, which is perhaps the most crisp and concise summary of the whole thing:

The proof of Biden’s ability to run the country is the fact that he is running it. Successfully. Not a debate performance against a pathological lying sociopath.

Maybe this is just me, but I immediately thought of Allen Iverson’s response to a question about practice from the media:

Listen, we talking about practice. Not a game, not a game, not a game. We talking about practice. Not a game, not the game that I go out there and die for and play every game like it’s my last. Not the game. We talking about practice, man.

While he might be fine at blustering his way through debates (practice), Trump, famously, was bad at being president and actually didn’t like the job (the game). Like, we don’t have to imagine how Trump would perform as president because he did the job, poorly & ruinously, for four years. Biden has logged 3.5 years as president and has been very productive on behalf of the American people. We can directly compare them! And their teams! Politics & governance is a team sport, and Trump’s team is a flaming dumpster fire. So let’s stop talking about practice (and the media’s horse race coverage) and start focusing on the game.

Rebecca Solnit: Why is the pundit class so desperate to push Biden out of the race?

I am not usually one to offer diagnoses of people I’ve never met, but it does seem like the pundit class of the American media is suffering from severe memory loss. Because they’re doing exactly what they did in the 2016 presidential race — providing wildly asymmetrical and inflammatory coverage of the one candidate running against Donald J Trump.

They have become a stampeding herd producing an avalanche of stories suggesting Biden is unfit, will lose and should go away, at a point in the campaign in which replacing him would likely be somewhere between extremely difficult and utterly catastrophic. They do this while ignoring something every scholar and critic of journalism knows well and every journalist should. As Nikole Hannah-Jones put it: “As media we consistently proclaim that we are just reporting the news when in fact we are driving it. What we cover, how we cover it, determines often what Americans think is important and how they perceive these issues yet we keep pretending it’s not so.” They are not reporting that he is a loser; they are making him one.

I’ve been watching this play out over the last few weeks and whatever the media (especially the NY Times) and pundits are doing here is much more alarming to me than Biden’s poor debate performance. Especially considering:

Speaking of coups, we’ve had a couple of late, which perhaps merit attention as we consider who is unfit to hold office. This time around, Trump is not just a celebrity with a lot of sexual assault allegations, bankruptcies and loopily malicious statements, as he was in 2016. He’s a convicted criminal who orchestrated a coup attempt to steal an election both through backroom corruption and public lies and through a violent attack on Congress. The extremist US supreme court justices he selected during his last presidential term themselves staged a coup this very Monday, overthrowing the US constitution itself and the principle that no one is above the law to make presidents into kings, just after legalizing bribery of officials, and dismantling the regulatory state by throwing out the Chevron deference.

*hair-tearing-out sounds*

I didn’t know what to expect from this 1937 video explanation of how wire photos were transmitted to newspapers, but a double stunt sequence featuring an airplane and a death-defying photographer was not anywhere on my bingo card. This starts kinda slow but it picks up once they get into the completely fascinating explanation of how they sent photographs across the country using ordinary telephone lines. The whole setup was portable and they just hacked into a wire on a telephone pole, asked the operator to clear the line, and sent a photo scan via an analog modem. Ingenious!

The Wikipedia page about wire photos is worth a read — French designers argued that the technology was responsible for an early form of fast fashion.

After World War II at haute couture shows in Paris, Frederick L. Milton would sketch runway designs and transmit his sketches via Bélinographe to his subscribers, who could then copy Parisian fashions. In 1955, four major French couturiers (Lanvin, Dior, Patou, and Jacques Fath) sued Milton for piracy, and the case went to the Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court. Wirephoto enabled a speed of transmission that the French designers argued damaged their businesses.

(via the kid should see this)

This is an interesting point by Chris Hayes about the difference between institutions (the NY Times, the Dept. of Justice, Facebook) trying to be independent and trying to be perceived as independent:

But here’s the rub, if your goal is to be perceived as independent, then you are wholly *dependent* on the perceptions of some group of people (in both cases conservatives/Republicans). And now, if you’re just courting their perceptions, then you’re no longer independent! In fact you’re the opposite; you’re entirely dependent on how they perceive you. You’ve just traded one form of audience or partisan capture for another!

Yesterday, there was yet another school shooting on a college campus, this time at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. A UNC graduate student walked into a classroom building and murdered a science professor with a gun. The campus was on lockdown for hours. The front page of The Daily Tar Heel today consists of text messages sent to and from students during the lockdown:

An incredible and powerful design — on Mastodon, Steve Silberman called it “the tombstone of democracy, courtesy of the NRA”. As a nation, we’ve spent more than 20 years and trillions of dollars fighting the “War on Terror” but won’t do a damn thing about the self-imposed terrorism of gun violence. The people sending and receiving those texts — they are TERRIFIED. And this happens regularly in the US, in pre-schools and on college campuses alike. We are a sick nation.

Now that the 2024 election campaigns have ramped up in earnest (absurdly & obscenely more than a year before the actual election), a good thing to keep in mind is NYU journalism professor Jay Rosen’s guidance for how journalists should cover the election:1

“Not the odds, but the stakes.”

That’s my shorthand for the organizing principle we most need from journalists covering the 2024 election. Not who has what chances of winning, but the consequences for our democracy. Not the odds, but the stakes.

Rosen first articulated this principle more than a decade ago and ever since reading about it a few years ago, I’ve all but stopped reading and linking to political horse race coverage. Who scored more “points” in the latest debate? Which candidate seems the most Presidential? Will his mugshot bolster his campaign? Come on, this isn’t the goddamned Oscars red carpet. Tell us what the candidates’ plans are and how they will affect how Americans live their lives. What experience do they have in governance? Or if not governance, in leadership? What do they believe, what actions have they taken in the past and what consequences have those actions had on actual people? What motivates them…power, money, fame, service? Many many people will not give a shit about any of this, but if we want to retain a functioning democracy with a press that’s not primarily about entertainment, voters need to know what they are getting into.

I enjoyed this Nieman Lab interview with Holden Foreman, the first-ever Accessibility Engineer at the Washington Post. I’m particularly pleased to see that Foreman is thinking about accessibility as, well, not solely a problem that can be solved by better engineering:

The coding is the easy part. Centering our work in listening, and elevating voices that have long been marginalized, is essential to improving accessibility in journalism. Trust has to be earned, and I think this is the biggest opportunity and challenge of being the first in this role. It’s counterproductive for accessibility work to be siloed from broader audience engagement and DEI work. Keeping that in mind, a lot of my initial work has included conversations with various stakeholders to get a better understanding of where and how engineering support, education, and documentation are needed. Accessibility may be viewed as a secondary concern or just a technical checklist if we don’t engage with real people in this area just as we do in others…

It’s essential to think about accessibility not just in the context of disability but also in the context of other inequities affecting news coverage and access to news. For instance, writing in plain language for users with cognitive disabilities can also benefit users with lower reading literacy. [The Post published a plain language version of Foreman’s introductory blog post.] Making pages less complex can make them more user-friendly and also possible to load in the first place for folks in areas with bad internet, etc…

There are nuances specific to the accessibility space. Not everyone with a disability has access to the same technology. Screen reader availability varies by operating system. JAWS, one of the popular screen readers, is not free to use. And there are many different types of disability. We cannot focus our work only on disabilities related to vision or hearing. We need separate initiatives to address separate accessibility issues.

Ultimately, better accessibility tools for disabled users translates to better services for everyone. That’s not the only reason to do it, but it is an undeniable benefit.

Paul Fairie has compiled a list of contenders for the best headline of 2022. They include:

‘How to Murder Your Husband’ writer guilty of murdering her husband

Started Out as a Fish. How Did It End Up Like This?

Monkey that was flushed down toilet, fed cocaine now has a boyfriend

The City of Ottawa wants to hear your garbage opinions

You can click through to see the rest and vote for the winners.

Michael Hobbes, late of You’re Wrong About, has made a video essay arguing that “cancel culture” is a moral panic and not some huge new problem in our society. He says you can tell it’s a moral panic because of the shifting definitions of the term, the stories are often exaggerated or untrue, the stakes are often low, and it’s fueling a reactionary backlash.

Even if you think that cancel culture really is a nationwide problem, I don’t see why we should focus on random college students and salty Twitter users rather than elected officials and actual legislation. Look, I’m not gonna sit here and pretend there haven’t been genuinely ugly internet pile-ons. Social media makes it easy to gang up on random people and ruin their lives over dumb jokes and honest mistakes.

But for two years now, right-wing grifters and the liberal rubes who launder them into the mainstream have cast cancel culture as a problem for the American left and a sign of creeping authoritarianism. They’re wrong. Internet mobs are not a left-wing phenomenon and historically speaking, the threat of authoritarianism usually comes from political parties that try to overturn elections, make it harder to vote, and censor ideas they don’t like. All of this is obvious, but that’s what moral panics do: they distract you from an obvious truth and make you believe in a stupid lie.

Back in October, Hobbes wrote a piece on The Methods of Moral Panic Journalism that pairs well with this video.

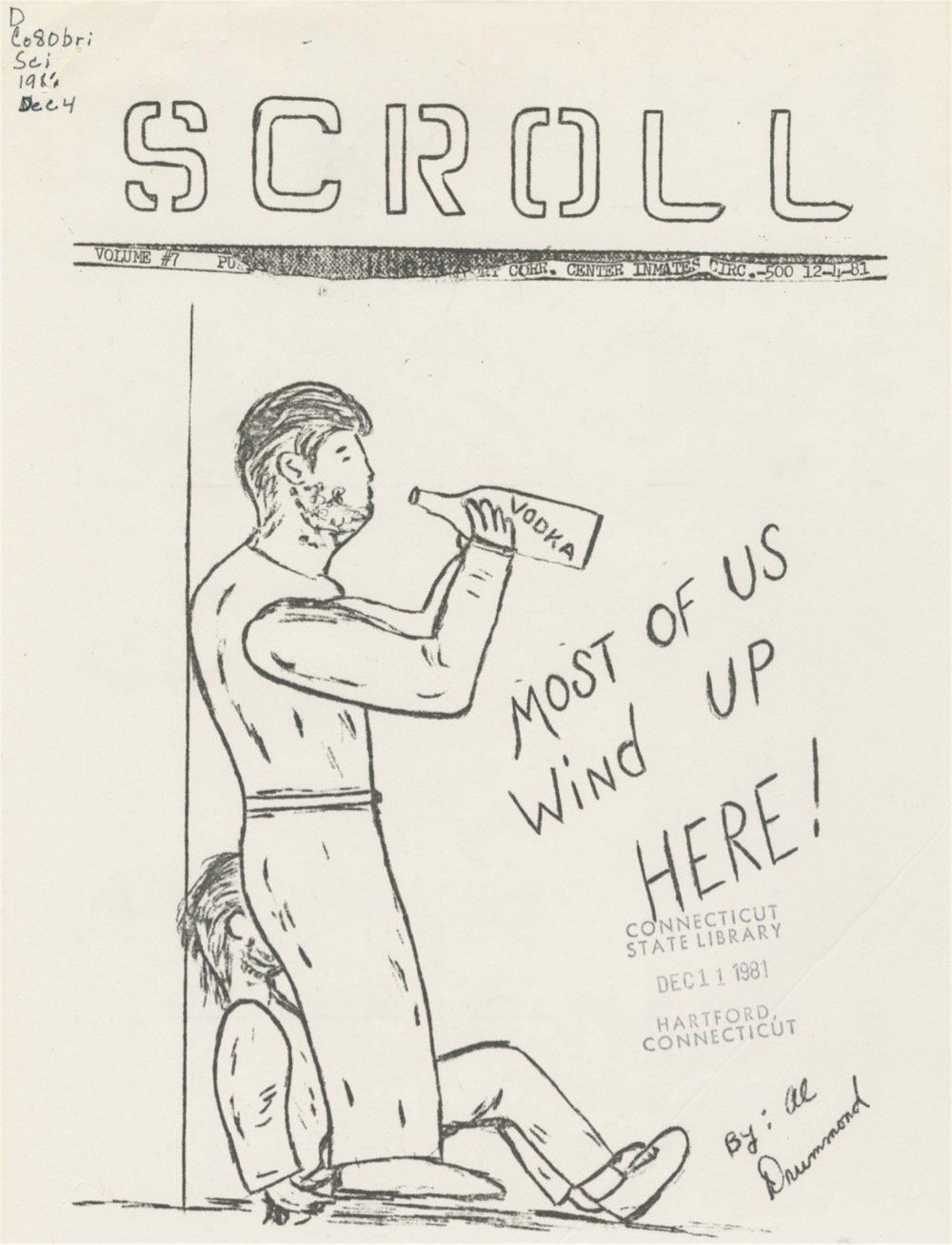

Since 1800, when the first newspaper was published in a NYC prison, over 500 newspapers have been published in prisons around the country. JSTOR is hosting a growing archive of such publications: American Prison Newspapers 1800-2020: Voices from the Inside.

With the United States incarcerating more individuals than any other nation — over 2 million as of 2019 — these publications represent a vast dimension of media history. These publications depict and report on all manner of life within the walls of prisons, from the quotidian to the upsetting. Incarcerated journalists walk a tightrope between oversight by administration — even censorship-and seeking to report accurately on their experiences inside. Some publications were produced with the sanction of institutional authorities; others were produced underground.

(thx, caroline)

Sarah Miller, author of this 2019 article on Miami real estate & rising oceans, recently wrote this resonant piece, All The Right Words On Climate Have Already Been Said.

I told her I didn’t have anything to say about climate change anymore, other than that I was not doing well, that I was miserable. “I am so unhappy right now.” I said those words. So unhappy. Fire season was not only already here, I said, but it was going to go on for at least four more months, and I didn’t know what I was going to do with myself. I didn’t know how I would stand the anxiety. I told her I felt like all I did every day was try to act normal while watching the world end, watching the lake recede from the shore, and the river film over, under the sun, an enormous and steady weight.

There’s only one thing I have to say about climate change, I said, and that’s that I want it to rain, a lot, but it’s not going to rain a lot, and since that’s the only thing I have to say and it’s not going to happen, I don’t have anything to say.

Miller continued:

Also, for what? Let’s give the article (the one she was starting to maybe think about asking me to write that I was wondering if I could write) the absolute biggest benefit of the doubt and imagine that people read it and said, “Wow, this is exactly how I feel, thanks for putting it into words.”

What then? What would happen then? Would people be “more aware” about climate change? It’s 109 degrees in Portland right now. It’s been over 130 degrees in Baghdad several times. What kind of awareness quotient are we looking for? What more about climate change does anyone need to know? What else is there to say?

This is where I am on the climate emergency most days now (and nearly there on the pandemic). Really, what the fuck else is there to say?

Zeynep Tufekci has written an important piece for The Atlantic on the mistakes that the media, public health officials, and the public keep making during the pandemic and how we can learn from them. A big one for me is how scientists & other public health officials and agencies communicate their knowledge to the public and how the media interprets and amplifies those messages.

Thus, on January 14, 2020, the WHO stated that there was “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission.” It should have said, “There is increasing likelihood that human-to-human transmission is taking place, but we haven’t yet proven this, because we have no access to Wuhan, China.” (Cases were already popping up around the world at that point.) Acting as if there was human-to-human transmission during the early weeks of the pandemic would have been wise and preventive.

Later that spring, WHO officials stated that there was “currently no evidence that people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection,” producing many articles laden with panic and despair. Instead, it should have said: “We expect the immune system to function against this virus, and to provide some immunity for some period of time, but it is still hard to know specifics because it is so early.”

Similarly, since the vaccines were announced, too many statements have emphasized that we don’t yet know if vaccines prevent transmission. Instead, public-health authorities should have said that we have many reasons to expect, and increasing amounts of data to suggest, that vaccines will blunt infectiousness, but that we’re waiting for additional data to be more precise about it. That’s been unfortunate, because while many, many things have gone wrong during this pandemic, the vaccines are one thing that has gone very, very right.

This pair of statements she highlights — “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission” and “There is increasing likelihood that human-to-human transmission is taking place, but we haven’t yet proven this, because we have no access to Wuhan, China” — are both factually true but the second statement is so much more helpful, useful, and far less likely to be misinterpreted by people who aren’t scientists that making the first statement is almost negligent.

Press Watch’s Dan Froomkin imagines a speech that new editoral leadership at large American newspapers should give to their political reporters.

It’s impossible to look out on the current state of political discourse in this country and think that we are succeeding in our core mission of creating an informed electorate.

It’s impossible to look out at the looming and in some cases existential challenges facing our republic and our globe — among them the pandemic, climate change, income inequality, racial injustice, the rise of disinformation and ethnic nationalism — and think that it’s OK for us to just keep doing what we’ve been doing.

He continues:

First of all, we’re going to rebrand you. Effective today, you are no longer political reporters (and editors); you are government reporters (and editors). That’s an important distinction, because it frees you to cover what is happening in Washington in the context of whether it is serving the people well, rather than which party is winning.

Historically, we have allowed our political journalism to be framed by the two parties. That has always created huge distortions, but never like it does today. Two-party framing limits us to covering what the leaders of those two sides consider in their interests. And, because it is appropriately not our job to take sides in partisan politics, we have felt an obligation to treat them both more or less equally.

Both parties are corrupted by money, which has badly perverted the debate for a long time. But one party, you have certainly noticed, has over the last decade or two descended into a froth of racism, grievance and reality-denial. Asking you to triangulate between today’s Democrats and today’s Republicans is effectively asking you to lobotomize yourself. I’m against that.

Defining our job as “not taking sides between the two parties” has also empowered bad-faith critics to accuse us of bias when we are simply calling out the truth. We will not take sides with one political party or the other, ever. But we will proudly, enthusiastically, take the side of wide-ranging, fact-based debate.

Government reporters. Yes, exactly. Worth reading in its entirety.

NY Times reporter Neil Sheehan, who was a Vietnam War correspondent, won a Pulitzer Prize, and obtained the Pentagon Papers for the Times, died yesterday at the age of 84. In an interview to be published posthumously, Sheehan revealed for the first time how he obtained the classified report on the Vietnam War from Daniel Ellsberg.

He also revealed that he had defied the explicit instructions of his confidential source, whom others later identified as Daniel Ellsberg, a former Defense Department analyst who had been a contributor to the secret history while working for the Rand Corporation. In 1969, Mr. Ellsberg had illicitly copied the entire report, hoping that making it public would hasten an end to a war he had come passionately to oppose.

Contrary to what is generally believed, Mr. Ellsberg never “gave” the papers to The Times, Mr. Sheehan emphatically said. Mr. Ellsberg told Mr. Sheehan that he could read them but not make copies. So Mr. Sheehan smuggled the papers out of the apartment in Cambridge, Mass., where Mr. Ellsberg had stashed them; then he copied them illicitly, just as Mr. Ellsberg had done, and took them to The Times.

Over the next two months, he strung Mr. Ellsberg along. He told him that his editors were deliberating about how best to present the material, and he professed to have been sidetracked by other assignments. In fact, he was holed up in a hotel room in midtown Manhattan with the documents and a rapidly expanding team of Times editors and reporters working feverishly toward publication.

What a wild tale. Read the whole thing…the kicker is worth it. Thanks to the efforts of Ellsberg, Sheehan, and other journalists, you can now read the complete non-redacted report on the National Archives website.

Caliphate, Rukmini Callimachi’s podcast for the NY Times about ISIS, was one of my favorite podcasts of 2018 — I recommended it in a post in June of that year. The NY Times has now retracted a central story in the podcast, that of an alleged ISIS executioner from Canada named Abu Huzayfah.

During the course of reporting for the series, The Times discovered significant falsehoods and other discrepancies in Huzayfah’s story. The Times took a number of steps, including seeking confirmation of details from intelligence officials in the United States, to find independent evidence of Huzayfah’s story. The decision was made to proceed with the project but to include an episode, Chapter 6, devoted to exploring major discrepancies and highlighting the fact-checking process that sought to verify key elements of the narrative.

In September — two and a half years after the podcast was released — the Canadian police arrested Huzayfah, whose real name is Shehroze Chaudhry, and charged him with perpetrating a terrorist hoax. Canadian officials say they believe that Mr. Chaudhry’s account of supposed terrorist activity is completely fabricated. The hoax charge led The Times to investigate what Canadian officials had discovered, and to re-examine Mr. Chaudhry’s account and the earlier efforts to determine its validity. This new examination found a history of misrepresentations by Mr. Chaudhry and no corroboration that he committed the atrocities he described in the “Caliphate” podcast.

As a result, The Times has concluded that the episodes of “Caliphate” that presented Mr. Chaudhry’s claims did not meet our standards for accuracy.

From a Times piece about Chaudhry’s hoax:

Before “Caliphate” aired, two American officials told The Times that Mr. Chaudhry had, in fact, joined ISIS and crossed into Syria. And some of the people who know and have counseled Mr. Chaudhry say they have no doubt that he holds extremist, jihadist views.

But Canadian law enforcement officials, who conducted an almost four-year investigation into Mr. Chaudhry, say their examination of his travel and financial records, social media posts, statements to the police and other intelligence make them confident that he did not enter Syria or join ISIS, much less commit the grievous crimes he described.

You can read more about this on NPR. Callimachi has been reassigned by the Times; the paper’s editor in chief Dean Baquet said, “I do not see how Rukmini could go back to covering terrorism after one of the highest profile stories of terrorism is getting knocked down in this way.”

Update: Here’s a statement from Callimachi on the retraction. It reads, in part:

Reflecting on what I missing in reporting our podcast is humbling. Thinking of the colleagues and the newsroom I let down is gutting. I caught the subject of our podcast lying about key aspects of his account and I reported that. I also didn’t catch other lies he told us, and I should have. I added caveats to try to make clear what we knew and what we didn’t. It wasn’t enough.

There are several listeners of the podcast in her mentions that do not feel as though they were misled. I’d have to go back and listen to the whole thing again to have an opinion, but I would like to note that Caliphate told a story and showed the behind-the-scenes at the same time. That non-traditional approach was really compelling, a key aspect of the show’s success IMO. Because you’re dealing with violent organizations and sealed investigations (neither ISIS nor government groups like the FBI want their information out there), there are limits on how stories like this can even be told. Callimachi and her colleagues creatively found a way to tell this one: by being upfront and transparent about those limitations and explicitly showing their work, misgivings and all. But perhaps, as she said, it wasn’t enough.

Media correspondents from all over the world spend months and years in the United States, reporting on our current events, politics, and culture. In this illuminating video from the New Yorker, several of them talk about what they think of our country. As outsiders, they’re able to see things that Americans don’t and can talk to people who may not otherwise feel comfortable talking to (what they perceive as) biased or corrupt American media. They’ve also observed an unprecedented level of division and are aware of the disconnect between America’s rhetoric about freedom and the sense that they’re reporting from a failed state.

The Black Music History Library is a list of resources (books, articles, podcasts, films, etc.) about the Black origins of popular and traditional music. From the about page:

There are many notable archives doing similar work, yet it isn’t uncommon for some to have a limited view of Black music — one which fuels US-centrism and a preference for vernacular music traditions. This collection considers the term “Black music” more widely, as it aims to address any instances in which Black participation led to the creation or innovation of music across the diaspora. Plainly speaking, that means just about every genre will be included here.

Black artists have often been minimized or omitted entirely when it comes to the discussion, practice, and research of many forms of music. This library seeks to correct that. It is time to reframe Black music history as foundational to American music history, Latinx music history, and popular music history at large.

The library was created by music journalist Jenzia Burgos after her Instagram slideshow went viral back in June, demonstrating a need for a more comprehensive resource. In a thread announcing the site, Burgos envisions the site as a “living library” that will shift and grow with reader contributions — you can send in resources via this form. (via @tedgioia)

Malofiej have announced their 28th International Infographics Awards for 2020, which they refer to as “the Pulitzers for infographics”. You can check out some of the top infographics here, culled from newspapers, magazines, and online media from around the world. The full list is available here, complete with links to the online winners.

For her series Counternarratives, artist and media critic Alexandra Bell takes newspaper articles and layouts from the NY Times that demonstrate racial bias and fixes them. For example, Bell took the notorious double profile of Michael Brown and his killer Darren Wilson and placed the focus entirely on Brown:

In this video, Bell explains her process:

I think everything is about race. Black communities, gay communities, immigrant communities feel a lot of media representations to be inadequate, biased. There’s a lot of reporting around police violence and black men, and I realized a lot of the arguments that we were having were about depictions. I started to wonder how different would it be if I swapped images or changed some of the text.

See also Kendra Pierre-Louis’ recent article for Nieman Lab: It’s time to change the way the media reports on protests. Here are some ideas.

The Washington Post made this short video that shows how Fox News personalities were talking about the COVID-19 pandemic a week or two ago — it’s a Democrat hoax!! — compared to their more recent coverage that aligns closer with the truth.

For weeks, some of Fox News’s most popular hosts downplayed the threat of the coronavirus, characterizing it as a conspiracy by media organizations and Democrats to undermine President Trump.

Fox News personalities such as Sean Hannity and Laura Ingraham accused the news media of whipping up “mass hysteria” and being “panic pushers.” Fox Business host Trish Regan called the alleged media-Democratic alliance “yet another attempt to impeach the president.”

It has never been more plain that Fox News is not journalism but conservative propaganda. They, along with Trump, some conservative members of Congress, and conservative talk radio, were just straight up lying, misleading the public, and peddling conspiracy theories until it became overwhelmingly clear that this is a serious situation, as experts had been saying for weeks. The video shows completely contradictory statements made by the same people days apart; as Andrew Kaczynski says, “what a damning indictment”. I’ll go further than that: Fox News endangered the lives of Americans with their false and misleading coverage. People will suffer and die unnecessarily because of it.

I’d urge you to show this to your red state relatives and ask them to defend Fox News as journalism, but I don’t think it will actually do any good. The whole point of propaganda is to deprive people of, as Hannah Arendt puts it, the “capacity to think and to judge”.

The moment we no longer have a free press, anything can happen. What makes it possible for a totalitarian or any other dictatorship to rule is that people are not informed; how can you have an opinion if you are not informed? If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer. This is because lies, by their very nature, have to be changed, and a lying government has constantly to rewrite its own history. On the receiving end you get not only one lie-a lie which you could go on for the rest of your days-but you get a great number of lies, depending on how the political wind blows. And a people that no longer can believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such a people you can then do what you please.

In recent years, many media outlets have joined publications like the WSJ and NY Times in erecting paywalls around their online offerings, giving visitors access to a few articles a month before asking them to pay for unlimited access. Due to the continuing worldwide COVID-19/coronavirus crisis and in order to make information about the pandemic more accessible to the public, several publications have dropped their paywalls for at least some of their coronavirus coverage (thanks to everyone who responded to my tweet about this).

Among them are The Atlantic, WSJ, Talking Points Memo, Globe and Mail, Seattle Times, Miami Herald (and other McClatchy-owned properties), Toronto Star, Stat, Dallas Morning News, Medium, NY Times, Washington Post, Baltimore Sun, Chicago Tribune, Christian Science Monitor and several medical/science journals. Notably, The Guardian relies on online subscription revenue but doesn’t put anything behind a paywall, including their coronavirus coverage.

In addition, a group of archivists have created an online directory of scientific papers related to coronaviruses, available for free download.

“These articles were always written to be shared with as many people as possible,” Reddit user “shrine,” an organizer of the archive, said in a call. “From every angle that you look at it, [paywalled research] is an immoral situation, and it’s an ongoing tragedy.”

Kudos to those media organizations for doing the right thing — this information can save people’s lives. Let’s hope others (*cough* Washington Post) will soon follow suit. And if you find the coverage helpful, subscribe to these outlets!

BTW, like The Guardian, kottke.org is supported by readers just like you who contribute to make sure that every single thing on the site is accessible to everyone. If you’re a regular reader, please consider supporting this experiment in openness.

Update: Added the NY Times to the list above. I am also hearing that many European papers are not dropping their paywalls in the face of the crisis.

Update: Added several media outlets to the list, including Washington Post and Chicago Tribune. At this point, it seems to be standard practice now (at least in the US & Canada) so this will be the final update. (thx, @maschweisguth)

I was reading this NY Times piece on their policies for reporters and editors around impartiality and politics — “newsroom staff members may not participate in political advocacy, like volunteering for candidates’ campaigns or making contributions” — and ran across this from the paper’s chief White House correspondent, Peter Baker:

As reporters, our job is to observe, not participate, and so to that end, I don’t belong to any political party, I don’t belong to any non-journalism organization, I don’t support any candidate, I don’t give money to interest groups and I don’t vote.

I try hard not to take strong positions on public issues even in private, much to the frustration of friends and family. For me, it’s easier to stay out of the fray if I never make up my mind, even in the privacy of the kitchen or the voting booth, that one candidate is better than another, that one side is right and the other wrong.

And similar perspectives from a 2008 Politico piece. Maybe it’s just me, but this seems like a deeply weird approach — and ultimately an intellectually dishonest one. Not voting is taking a political position — a passive one perhaps, but a political position nonetheless.1 There’s no direct analogy to not voting or not taking private positions on political issues for other areas of reporting, but just imagine being a technology reporter who doesn’t own a mobile phone or computer because they don’t want to show favoritism towards Apple or Samsung, a food reporter who is unable to dine at restaurants outside of work, or a style reporter who can’t wear any clothes they didn’t make themselves. Absurd, right? We do live in an age of too much opinion dressed up as news, but pretending not to have opinions ultimately does harm to a public in need of useful contextual information.

The long-time host of PBS NewsHour Jim Lehrer died this week at the age of 85. In this age of news as entertainment and opinion as news, Lehrer seems like one of the last of a breed of journalist who took seriously the integrity of informing the American public about important events. In a 1997 report by The Aspen Institute, Lehrer outlined the guidelines he adhered to in practicing journalism:

- Do nothing I cannot defend.*

- Do not distort, lie, slant, or hype.

- Do not falsify facts or make up quotes.

- Cover, write, and present every story with the care I would want if the story were about me.*

- Assume there is at least one other side or version to every story.*

- Assume the viewer is as smart and caring and good a person as I am.*

- Assume the same about all people on whom I report.*

- Assume everyone is innocent until proven guilty.

- Assume personal lives are a private matter until a legitimate turn in the story mandates otherwise.*

- Carefully separate opinion and analysis from straight news stories and clearly label them as such.*

- Do not use anonymous sources or blind quotes except on rare and monumental occasions. No one should ever be allowed to attack another anonymously.*

- Do not broadcast profanity or the end result of violence unless it is an integral and necessary part of the story and/or crucial to understanding the story.

- Acknowledge that objectivity may be impossible but fairness never is.

- Journalists who are reckless with facts and reputations should be disciplined by their employers.

- My viewers have a right to know what principles guide my work and the process I use in their practice.

- I am not in the entertainment business.*

In his 2006 Harvard commencement address, Lehrer reduced that list to an essential nine items (marked with an * above).

These are fantastic guidelines; as veteran journalist Al Thompkins said recently: “I would like to add a 10th rule: Journalists should be more like Jim Lehrer.”

Addendum: Even though this is a mere blog that has different goals and moves at a different pace than traditional journalism, I try (try!) to adhere to Lehrer’s guidelines on kottke.org as much as possible. I found out about his rules on Twitter in the form of a context-free screenshot of an equally context-free PDF. Lehrer would not approve of this sort of sourcing, so I started to track it down.

All initial attempts at doing so pointed to the truncated list (as outlined in the Harvard speech and in this 2009 episode of the NewsHour), so I wrote up a post with the nine rules and was about to publish — but something about the longer list bugged me. Why would someone add more rules and attribute them to Lehrer? It didn’t seem to make sense, so I dug a little deeper and eventually found the Aspen report in bowels of Google and rewrote the post.

In doing all this, I rediscovered one of the reasons why Lehrer’s guidelines aren’t followed by more media outlets: this shit takes time! And time is money. It would have taken me five minutes to find that context-free PDF, copy & paste the text, throw a post together, and move on to something else. But how can I do that when I don’t know for sure the list is accurate? Did he write or say those things verbatim? Or was it paraphrased or compiled from different places? Maybe the transcription is wrong. Lehrer, of all people, and this list, of all lists, deserves proper attribution. So this post actually took me 45+ minutes to research & write (not counting this addendum). And this is just one little list that in the grand and cold economic scheme of things is going to make me exactly zero more dollars than the 5-minute post would have!

Actual news outlets covering actual news have an enormous incentive to cut corners on this stuff, especially when news budgets have been getting squeezed on all sides for the better part of the last two decades. It should come as no big surprise then that the media covers elections as if they were horse races, feasts on the private lives of celebrities, and leans heavily on entertaining opinions — that all sells better than Lehrer’s guidelines do — but we should think carefully about whether we want to participate in it. In the age of social media, we are no longer mere consumers of news — everyone is a publisher and that’s a powerful thing. So perhaps Lehrer’s guidelines should apply more broadly, not only for us as individuals but also for media companies like Google, Facebook, and Twitter that amplify and leverage our thoughts and reporting for their own ends.

From Future Crunch, 99 Good News Stories You Probably Didn’t Hear About in 2019. Here are a few representative entries:

8. In Kenya, poaching rates have dropped by 85% for rhinos and 78% for elephants in the last five years, in South Africa, the number of rhinos killed by poachers fell by 25%, the fifth annual decrease in a row, and in Mozambique, one of Africa’s largest wildlife reserves went an entire year without losing a single elephant.

16. China’s tree stock rose by 4.56 billion m^3 between 2005 and 2018, deserts are shrinking by 2,400 km^2 a year, and forests now account for 22% of land area. SCMP

38. Type 3 polio officially became the second species of poliovirus to be eliminated in 2019. Only Type 1 now remains — and only in Pakistan and Afghanistan. STAT

We definitely don’t hear enough good news from most of our media sources. It’s mostly bad news and “feel good” news — that’s what sells. (Note that “feel good” news is not the same as substantive good news and is sometimes even bad news, e.g. heartwarming stories that are actually indicators of societal failures.) In the past few weeks I’ve also posted links to Beautiful News Daily and The Happy Broadcast, a pair of sites dedicated to sharing positive news about the world.

But at this point I feel obligated to remind myself (and perhaps you as well) that focusing mostly on positive news isn’t great either. A number of thinkers — including Bill Gates, Steven Pinker, Nicholas Kristof, Max Roser — are eager to point out that the world’s citizens have never been safer, healthier, and wealthier than they are now. And in some ways that is true! But in this long piece for The Guardian, Oliver Burkeman addresses some of the reasons to be skeptical of these claims.

But the New Optimists aren’t primarily interested in persuading us that human life involves a lot less suffering than it did a few hundred years ago. (Even if you’re a card-carrying pessimist, you probably didn’t need convincing of that fact.) Nestled inside that essentially indisputable claim, there are several more controversial implications. For example: that since things have so clearly been improving, we have good reason to assume they will continue to improve. And further — though this is a claim only sometimes made explicit in the work of the New Optimists — that whatever we’ve been doing these past decades, it’s clearly working, and so the political and economic arrangements that have brought us here are the ones we ought to stick with. Optimism, after all, means more than just believing that things aren’t as bad as you imagined: it means having justified confidence that they will be getting even better soon.

See also other critiques of Pinker’s work: A letter to Steven Pinker (and Bill Gates, for that matter) about global poverty and The World’s Most Annoying Man.

For the past couple of years, Mauro Gatti has been publishing The Happy Broadcast, his antidote to negative news and “the vitriolic rhetoric that pervades our media”. Here are a couple of recent examples:

You can also follow The Happy Broadcast on Instagram. See also Beautiful News Daily.

In a keynote address to the Anti-Defamation League, entertainer Sacha Baron Cohen calls the platforms created by Facebook, Google, Twitter, and other companies “the greatest propaganda machine in history” and blasts them for allowing hate, bigotry, and anti-Semitism to flourish on these services.

Think about it. Facebook, YouTube and Google, Twitter and others — they reach billions of people. The algorithms these platforms depend on deliberately amplify the type of content that keeps users engaged — stories that appeal to our baser instincts and that trigger outrage and fear. It’s why YouTube recommended videos by the conspiracist Alex Jones billions of times. It’s why fake news outperforms real news, because studies show that lies spread faster than truth. And it’s no surprise that the greatest propaganda machine in history has spread the oldest conspiracy theory in history- — the lie that Jews are somehow dangerous. As one headline put it, “Just Think What Goebbels Could Have Done with Facebook.”

On the internet, everything can appear equally legitimate. Breitbart resembles the BBC. The fictitious Protocols of the Elders of Zion look as valid as an ADL report. And the rantings of a lunatic seem as credible as the findings of a Nobel Prize winner. We have lost, it seems, a shared sense of the basic facts upon which democracy depends.

When I, as the wanna-be-gansta Ali G, asked the astronaut Buzz Aldrin “what woz it like to walk on de sun?” the joke worked, because we, the audience, shared the same facts. If you believe the moon landing was a hoax, the joke was not funny.

When Borat got that bar in Arizona to agree that “Jews control everybody’s money and never give it back,” the joke worked because the audience shared the fact that the depiction of Jews as miserly is a conspiracy theory originating in the Middle Ages.

But when, thanks to social media, conspiracies take hold, it’s easier for hate groups to recruit, easier for foreign intelligence agencies to interfere in our elections, and easier for a country like Myanmar to commit genocide against the Rohingya.

In particular, he singles out Mark Zuckerberg and a speech he gave last month.

First, Zuckerberg tried to portray this whole issue as “choices…around free expression.” That is ludicrous. This is not about limiting anyone’s free speech. This is about giving people, including some of the most reprehensible people on earth, the biggest platform in history to reach a third of the planet. Freedom of speech is not freedom of reach. Sadly, there will always be racists, misogynists, anti-Semites and child abusers. But I think we could all agree that we should not be giving bigots and pedophiles a free platform to amplify their views and target their victims.

Second, Zuckerberg claimed that new limits on what’s posted on social media would be to “pull back on free expression.” This is utter nonsense. The First Amendment says that “Congress shall make no law” abridging freedom of speech, however, this does not apply to private businesses like Facebook. We’re not asking these companies to determine the boundaries of free speech across society. We just want them to be responsible on their platforms.

If a neo-Nazi comes goose-stepping into a restaurant and starts threatening other customers and saying he wants kill Jews, would the owner of the restaurant be required to serve him an elegant eight-course meal? Of course not! The restaurant owner has every legal right and a moral obligation to kick the Nazi out, and so do these internet companies.

Jeff Jarvis with some good comments (based primarily on a paper by Axel Bruns) arguing that the media in general needs to start with deeper questions, more research, referencing actual research, and demonstrable facts instead of presumptions. Excellent ideas.

He begins with this quote from the Bruns paper:

[T]hat echo chambers and filter bubbles principally constitute an unfounded moral panic that presents a convenient technological scapegoat (search and social platforms and their affordances and algorithms) for a much more critical problem: growing social and political polarisation. But this is a problem that has fundamentally social and societal causes, and therefore cannot be solved by technological means alone. [Emphasis mine.]

Agreed. Jarvis via Bruns then argues that these metaphors are too loosely defined, leaving room for broad usage, unclear meaning, resulting in moral panic more than actual research and fact based analysis.

He follows up with a number of articles and further research from the paper, backing up his point. Then numerous examples of media using the filter bubble shortcut. I encourage you to click through to the article and dive a bit deeper.

But that leads to another journalistic weakness in reporting academic studies: stories that takes the latest word as the last word.

Absolutely. And pretty much everyone does that at some point so it’s a good reminder to us all to consider new research and explanations of the day within broader historical context and preexisting knowledge.

The whole article (and the research paper, although I myself haven’t gotten to that yet) is worth a read, the main point of Jarvis is a good one; more questions, more research, deeper thinking. Looking at people and how they use the technology, not just the tech itself.

I do have to caveat this though by mentioning the Jarvis dismisses Shoshana Zuboff’s work on Surveillance Capitalism by portraying it as “an extreme name for advertising cookies and the use of the word devalues the seriousness of actual surveillance by governments.” One could debate whether Zuboff should have used another word, separating the practice from that of governments, but by saying “advertising cookies” Jarvis makes one of those surface remarks he raves against in his piece, somewhat discrediting it.

Older posts

Stay Connected