kottke.org posts about flying

Really fascinating piece by Michael Habib in Scientific American about how amazing feathers are: they come in so many different shapes and sizes and do so many things (insulate, keep dry, flying, noise dampening, etc. etc. etc.) And I loved the opening anecdote:

In October 2022 a bird with the code name B6 set a new world record that few people outside the field of ornithology noticed. Over the course of 11 days, B6, a young Bar-tailed Godwit, flew from its hatching ground in Alaska to its wintering ground in Tasmania, covering 8,425 miles without taking a single break. For comparison, there is only one commercial aircraft that can fly that far nonstop, a Boeing 777 with a 213-foot wingspan and one of the most powerful jet engines in the world. During its journey, B6-an animal that could perch comfortably on your shoulder-did not land, did not eat, did not drink and did not stop flapping, sustaining an average ground speed of 30 miles per hour 24 hours a day as it winged its way to the other end of the world.

Many factors contributed to this astonishing feat of athleticism-muscle power, a high metabolic rate and a physiological tolerance for elevated cortisol levels, among other things. B6’s odyssey is also a triumph of the remarkable mechanical properties of some of the most easily recognized yet enigmatic structures in the biological world: feathers. Feathers kept B6 warm overnight while it flew above the Pacific Ocean. Feathers repelled rain along the way. Feathers formed the flight surfaces of the wings that kept B6 aloft and drove the bird forward for nearly 250 hours without failing.

Ok, I said no more eclipse posts (maybe) and then posted like two or three more, but really this is the last one — maybe! In 1973, a group of scientists witnessed the longest ever total solar eclipse by flying in the shadow (umbra) of the moon in a Concorde prototype for 74 minutes over the Sahara desert. From the abstract of a paper in Nature about the flight:

On June 30, 1973, Concorde 001 intercepted the path of a solar eclipse over North Africa, Flying at Mach 2.05 the aircraft provided seven observers from France, Britain and the United States with 74 min of totality bounded by extended second (7 min) and third (12 min) contacts. The former permitted searches for time variations of much longer period than previously possible and the latter provided an opportunity for chromospheric observations of improved height resolution. The altitude, which varied between 16,200 and 17,700 m, freed the observations from the usual weather problems and greatly reduced atmospheric absorption and sky noise in regions of the infrared.

Mach 2.05 = 1573 mph = 2531 km/h. 17,700 m = 58,000 ft. They added portholes to the roof of the plane for better viewing and data gathering. This page on Xavier Jubier’s site contains lots of amazing details about the flight, including a map of the flight’s path compared to the umbra, photos of the retrofitted plane, and a graph of the umbra’s velocity across the surface of the Earth (which shows that for at least part of the eclipse, the Concorde was actually outrunning the moon’s shadow).

By flying inside the umbral shadow cone of the Moon at the same speed, the Concorde was going to stay in the darkness for nearly 74 minutes, the time for astronomers and physicists on board to do all the experiences they could imagine to complete during this incredible period of black Sun. They were able to achieve in one hour and fifteen minutes what would have taken decades by observing fifteen total solar eclipses from places that would have not necessarily gotten clear skies.

And finally, here’s a 30-minute French documentary from 1973 about the eclipse flight.

So. Cool!

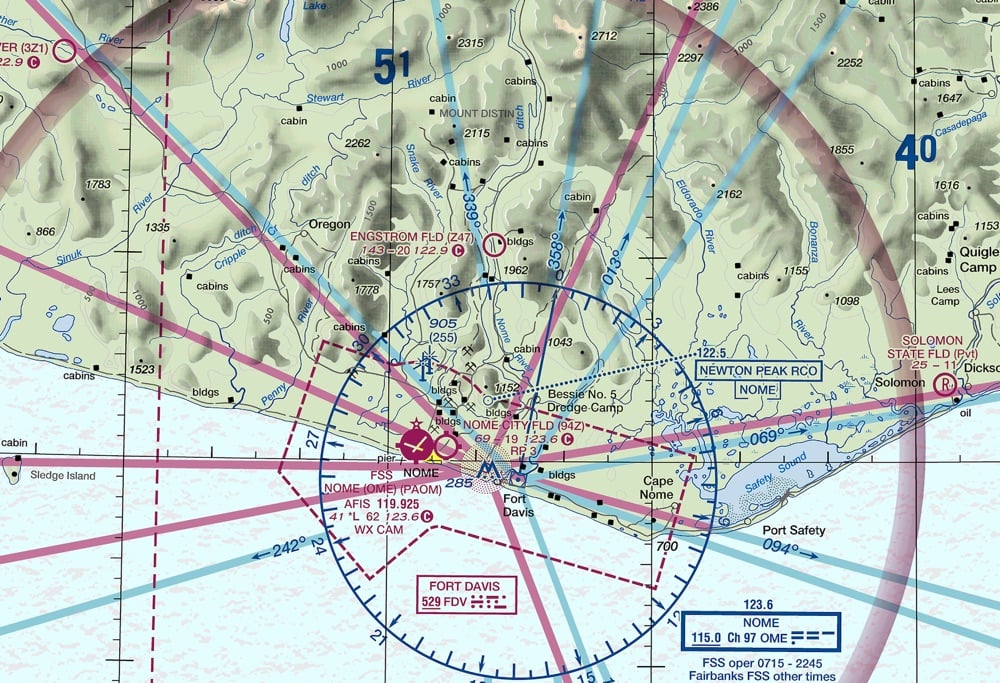

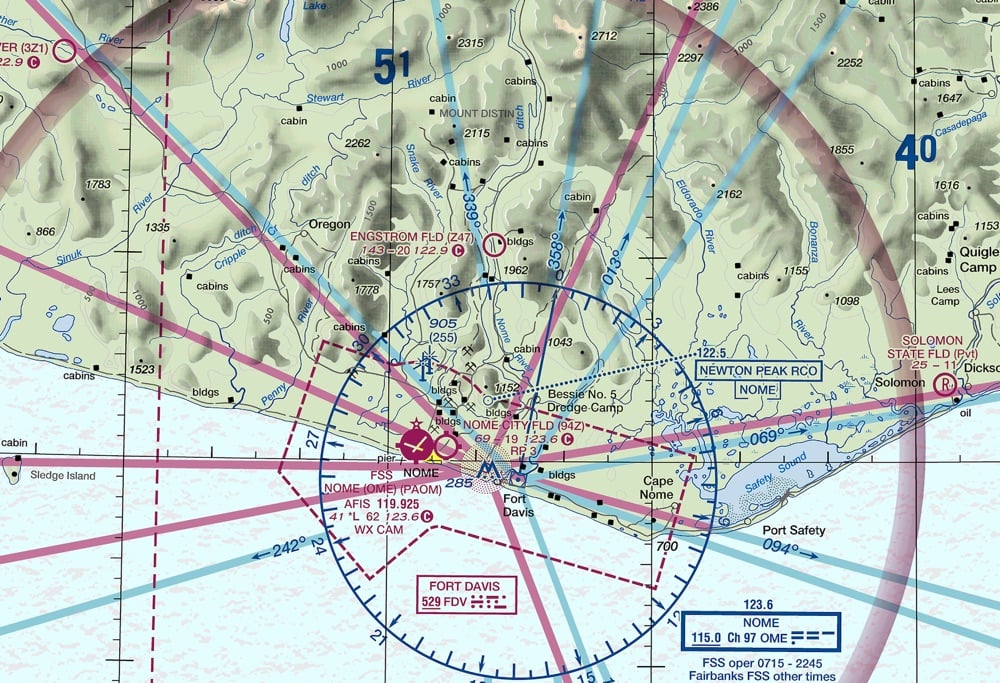

On Beautiful Public Data, Jon Keegan highlights the extremely information-rich flight maps produced by the Federal Aviation Administration that pilots use to find their way around the skies.

Among all of the visual information published by the U.S. government, there may be no product with a higher information density than the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) aviation maps. Intended for pilots, the FAA publishes free detailed maps of the entire U.S. airspace, and detailed maps of airports and their surroundings and updates them frequently. The density of the critical information layered on these maps is staggering, and it is a miracle that pilots can easily decipher these maps’ at a glance.

Oh wow, this takes me back. My dad was a pilot when I was a kid and he had a bunch of FAA maps in the house, in his planes, and even on the walls of his office. I remember finding these maps both oddly beautiful and almost completely inscrutable. What a treat to be able to finally figure out how to read them, at least a little bit. And the waypoint names are fun too:

Orlando, FL has many Disney themed waypoints such as JAFAR, PIGLT, JAZMN, TTIGR, MINEE, HKUNA and MTATA. Flying into Orlando, your plane might use the SNFLD arrival path, taking you past NOOMN, FORYU, SNFLD, JRRYY and GTOUT.

Based on the waypoints near Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International, this airport must be home to some of the nerdiest air traffic controllers. There’s a crazy number of Lord of the Rings waypoints: HOBTT, SHYRE, FRDDO, BLLBO, BGGNS, NZGUL, RAETH, ORRKK, GOLLM, ROHUN, GONDR, GIMLY, STRDR, SMAWG and GNDLF.

The NY Times asked a bunch of their readers what their favorite airport amenities were. Their answers included libraries, pools, and vending machines for things like cupcakes and canned cheese.

I love an airport with an outdoor area and areas for napping and free showers (like at Incheon). But my favorite airport thing by far is the bonkers indoor waterfall and garden/forest at Singapore’s Jewel Changi Airport:

What about you? What are your favorite airport shops, facilities, and conveniences when you travel? (Let’s not do “faster security” and such — that’s a given.)

Zeynep Tufekci writes about what makes airplane travel so safe, even when things go wrong (as with the Airbus A350 in Japan and the Alaska Airlines Boeing 737 Max 9 incidents).

Both incidents could have been much worse. And that everyone on both airliners walked away is, indeed, a miracle — but not the kind most people think about. They’re miracles of regulation, training, expertise, effort, constant improvement of infrastructure, as well as professionalism and heroism of the crew.

But these brave and professional men and women were standing on the shoulders of giants: competent bureaucrats; forensic investigators dispatched to accident investigations; large binders (nowadays digital) with hundreds and hundreds of pages of meticulously collected details of every aspect of accidents and near misses; constant training and retraining not just of the pilots but the cabin, ground, traffic control and maintenance crews; and a determined ethos that if something has gone wrong, the reason will be identified and fixed.

As Tufekci notes, when the capitalists are left to their own devices, corners are cut in the pursuit of shareholder value:

The Boeing 737 Max line holds other lessons. After two eerily similar back-to-back crashes in 2018 and 2019, killing 346 people total, the planes were grounded. At first, some rushed to blame inexperienced pilots or software gone awry. But the world soon learned that the real problem had been corporate greed that had taken too many shortcuts while the regulators hadn’t managed to resist the onslaught.

Santiago Borja is an airline pilot who takes stunning photos of storms and clouds from the flight deck of his 767. Definitely offers up a different perspective than the typical storm chaser photography. You can find his work on his website, on Instagram, and in book form.

As I’ve discussed previously, the Piper Super Cub is an amazing short takeoff and landing airplane that can, under the right conditions, takeoff and land in as little as 10 or 20 feet of runway.

In a recent stunt for Red Bull, Luke Czepiela landed a Super Cub on an 88-foot-wide helipad located on the 56th story of the Burj Al Arab Hotel in Dubai. Fantastic. And I love what he did right afterwards… (via digg)

Here’s what a whirring helicopter blade looks like, from the perspective of a GoPro strapped to the blade. The video is in slow motion — shot at 240 fps and displayed at 30 fps. Here’s what the blade looks like in flight and upside-down while doing a flip. (via clive thompson)

In a recent piece for The Guardian, Dave Eggers observes that we now have actual jetpacks that actually fly, an invention that was supposed to alert humanity that The Future had finally arrived,1 and no one really cares too much about them.

We have jetpacks and we do not care. An Australian named David Mayman has invented a functioning jetpack and has flown it all over the world — once in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty — yet few people know his name. His jetpacks can be bought but no one is clamouring for one. For decades, humans have said they want jetpacks, and for thousands of years we have said we want to fly, but do we really? Look up. The sky is empty.

Eggers, an avid flyer but not pilot, decided to take a jetpack flying lesson, just to see what none of the fuss is about.

When he returns and begins pouring the fuel into the jetpack, only then does it register just how dicey this seems, and why jetpacks have been slow to be developed and adopted. Though every day we fill our cars’ tanks with highly flammable gasoline, there is — or we pretend there is — a comfortable distance between our frail flesh and this explosive fuel. But carrying this fuel on your back, in a glorified backpack of tubes and turbines, brings the reality of the internal combustion engine home. Just watching the kerosene getting poured into the pack, inches from Wesson’s face, is unsettling.

And then there’s the noise:

Jarry asks if I’m ready. I tell him I’m ready. The jets ignite. The sound is like a category 5 hurricane passing through a drainpipe. Jarry turns an invisible throttle, and I mimic his movements with the real throttle. The sound grows louder. He turns his invisible throttle more, and I turn mine. Now the sound hits a fever pitch, and I feel the thrust down the back of my calves. I step ever so slightly forward, and lock my legs together. (This is why jetpack wearers have their legs stiff like toy soldiers - any deviation is quickly punished by 800-degree jet exhaust.) Jarry mimes more throttle, I give it more throttle, and slowly I leave the earth. It is nothing like weightlessness. Instead, I feel my every pound, feel just how much thrust it takes to get me and this machine to levitate.

Jarry tells me to go higher. One foot, then two, then three. As the jets howl and the kerosene burns, I hover, thinking that this is an astounding amount of noise and trouble to float 36in off the ground. Unlike the purest kinds of flight, which harness wind and master soaring, this is just brute force. This is busting through space with heat and noise. And it’s really difficult, too.

(via clive thompson)

Seatback Safety is home to a collection of dozens of seatback safety cards from airlines like Pan Am, United, Continental, Emirates, British Airways, JetBlue, and Air France.

Here’s the rationale for the site:

As a professional designer, it can be valuable to contemplate how practitioners solved the same problem over time with different fashions and different tools.

Seatback Safety cards have been used since the dawn of commercial flight. While their pamphlet form has remained largely the same for a century, they have significantly evolved in ways that reflected broader social and technological trends.

P.S. Did you remember that Hooters had an airline? (It only lasted three years.)

In trying to explain what you’re about to see here, I cannot improve upon the Dr. Adrian Smith’s narration at the beginning of this video:

But sometimes I think the most useful thing I can do as a scientist is to point the fancy science cameras at some moths flapping their wings in front of a purple backdrop. I mean, whose day isn’t going to be better after watching a pink and purple rosy maple moth flying in super slow motion? This is a polyphemus moth, a gigantic species of silk moth. What you are seeing, like all the rest of the clips in this video, was filmed at 6,000 frames per second.

Most of the moths in the video are delightfully fuzzy and chonky — if these moths were birds, they’d be birbs. Shall we call them mopfs?

The rest of Smith’s AntLab videos are worth looking through — I’ve previously posted about his slow motion videos here. (via aeon)

This video and blog post look at the challenges of building and maintaining a 3000-meter ice runway in Antarctica. It bears some resemblance to grooming ski slopes and maintaining ice rinks.

Once the snow is removed, the runway is inspected for cracks, pits, or any other deficiencies that would prevent a safe landing. These are repaired by crews with a mixture of cold water, ice chips, and snow that is poured on, allowed to harden, and then smoothed over.

Finally, two snow groomers with tillers grind a small layer of ice to create a top layer of crushed snow and ice that gives the runway the necessary friction for aircraft to operate. Lidström points out that equipment at Troll isn’t necessarily purpose built, ‘These are the same machines that you see on ski slopes, but with a tiller grinder attached.’

There’s even a small terminal with bathrooms and wifi, amenities which aren’t available at all Antarctic airfields.

Harry Everett Smith was an artist and a collector. One of the things he collected was paper airplanes — he picked up hundreds of them from the streets and buildings of New York between 1961 and 1983.

Smith was “always, always, always looking” for new airplanes, one friend said: “He would run out in front of the cabs to get them, you know, before they got run over. I remember one time we saw one in the air and he was just running everywhere trying to figure out where it was going to be. He was just, like, out of his mind, completely. He couldn’t believe that he’d seen one. Someone, I guess, shot it from an upstairs building.”

The whereabouts of much of his collection is presently unknown, but photos of part of the collection were compiled into a book: Paper Airplanes: The Collections of Harry Smith: Catalogue Raisonné, Volume I. You can see more of Smith’s collection at the New Yorker and SFO Museum. (via moss & fog)

Research biologist Adrian Smith, who specializes in insects, recently filmed a number of different types of flying insects taking off and flying away at 3200 frames/sec. Before watching, I figured I’d find this interesting — flying and slow motion together? sign me up! — but this video was straight-up mesmerizing with just the right amount of informative narration from Smith. There’s such an amazing diversity in wing shape and flight styles among even this small group of insects; I had to keep rewinding it to watch for details that I’d missed. Also, don’t miss the fishfly breaking the fourth wall by looking right at the camera while taking off at 6:07. I see you, my dude.

Smith has previously captured flying ants in slow motion and this globular springtail bug that spins through the air at more than 22,000 rpm. (via moss & fog)

For his piece The 3 Weeks That Changed Everything in The Atlantic, James Fallows talked to many scientists, health experts, and government officials about the US government’s response to the pandemic. In the article, he compares the pandemic response to how the government manages air safety and imagines what it would look like if we investigated the pandemic catastrophe like the National Transportation Safety Board investigates plane crashes.

Consider a thought experiment: What if the NTSB were brought in to look at the Trump administration’s handling of the pandemic? What would its investigation conclude? I’ll jump to the answer before laying out the background: This was a journey straight into a mountainside, with countless missed opportunities to turn away. A system was in place to save lives and contain disaster. The people in charge of the system could not be bothered to avoid the doomed course.

And he continues:

What happened once the disease began spreading in this country was a federal disaster in its own right: Katrina on a national scale, Chernobyl minus the radiation. It involved the failure to test; the failure to trace; the shortage of equipment; the dismissal of masks; the silencing or sidelining of professional scientists; the stream of conflicting, misleading, callous, and recklessly ignorant statements by those who did speak on the national government’s behalf. As late as February 26, Donald Trump notoriously said of the infection rate, “You have 15 people, and the 15 within a couple of days is going to be down close to zero.” What happened after that — when those 15 cases became 15,000, and then more than 2 million, en route to a total no one can foretell — will be a central part of the history of our times.

But he rightly pins much of the blame for the state we’re in on the Trump administration almost completely ignoring the plans put into place for a viral outbreak like this that were developed by past administrations, both Republican and Democratic alike.

In cases of disease outbreak, U.S. leadership and coordination of the international response was as well established and taken for granted as the role of air traffic controllers in directing flights through their sectors. Typically this would mean working with and through the World Health Organization — which, of course, Donald Trump has made a point of not doing. In the previous two decades of international public-health experience, starting with SARS and on through the rest of the acronym-heavy list, a standard procedure had emerged, and it had proved effective again and again. The U.S, with its combination of scientific and military-logistics might, would coordinate and support efforts by other countries. Subsequent stages would depend on the nature of the disease, but the fact that the U.S. would take the primary role was expected. When the new coronavirus threat suddenly materialized, American engagement was the signal all other participants were waiting for. But this time it did not come. It was as if air traffic controllers walked away from their stations and said, “The rest of you just work it out for yourselves.”

From the U.S. point of view, news of a virulent disease outbreak anywhere in the world is unwelcome. But in normal circumstances, its location in China would have been a plus. Whatever the ups and downs of political relations over the past two decades, Chinese and American scientists and public-health officials have worked together frequently, and positively, on health crises ranging from SARS during George W. Bush’s administration to the H1N1 and Ebola outbreaks during Barack Obama’s. As Peter Beinart extensively detailed in an Atlantic article, the U.S. helped build China’s public-health infrastructure, and China has cooperated in detecting and containing diseases within its borders and far afield. One U.S. official recalled the Predict program: “Getting Chinese agreement to American monitors throughout their territory — that was something.” But then the Trump administration zeroed out that program.

Americans, and indeed everyone in the world, should be absolutely furious about this, especially since the situation is actively getting worse after months (months!) of inactivity by the federal government.

From The Washington Post, an illustrated encyclopedia of sleeping positions on a plane. Economy only…we don’t need to see how peacefully the lie-flat fancies in business are slumbering. Tag yourself! (I’m a Bobblehead.)

From the catalog of the National Archives, a drawing from US Patent #95513 filed by W.F. Quinby in 1869 for “Improvement in Flying-Machines”. This could easily be the cover of a lost 2003 Neutral Milk Hotel album. (via @john_overholt)

In this video, CGP Grey investigates fast and not-so-fast methods for boarding commercial airline flights. Most airlines board passengers using the relatively slow back-to-front method — with a bit of the even slower front-to-back method at the start for first, business, premium economy, and frequent flying passengers — even though boarding in a random order would be quicker. In 2008, physicist Jason Steffen determined the optimal boarding method, which involves passengers boarding in a precise order to minimize people waiting for other people putting their luggage in the overhead bin.

Reagan Ray has collected a bunch of classic logos from American airlines, from the big ones (Delta, United) to small regional airlines (Pennsylvania Central, Cardiff and Peacock) to those no longer with us (Pan Am, TWA, Northwest). I sent him the logo for my dad’s old airline, Blue Line Air Express…I hope it makes it in!

See also Reagan’s collections of record label logos, 80s action figure logos, American car logos, VHS distributor logos, and railway logos. Careful, you might spend all day on these… (via @mrgan)

Update: Ray was kind enough to add Blue Line into the mix! Thank you!

Float is a feature-length documentary film directed by Phil Kibbe about “the ultra-competitive sport of elite, stunningly-designed indoor model airplanes”. The main action of the film takes place at the F1D World Championships in Romania, where competitors from all over the world build delicately beautiful rubber-band-powered airplanes and compete to keep them afloat the longest.

After devoting years of time into construction and practice for no material reward, glory becomes their primary incentive. Like any competition, cheating and controversy are an integral part of the sport. FLOAT follows the tumultuous journey of Brett Sanborn and Yuan Kang Lee, two American competitors as they prepare for and compete at the World Championships.

“Designing, building, and flying the planes is truly an experience that requires patience and zen-like focus,” says Ben Saks, producer and subject in the film.

Float began as a Kickstarter project back in 2012…congrats to the team for their patience in getting it finished.

For more than 20 years, Christian Moullec has been flying with migratory birds in his ultralight aircraft. He raises birds of vulnerable species on his farm and then when it’s time for them to migrate, he shows them how, guiding them along safe migration paths. To support his conservation efforts, Moullec takes paying passengers up with him to fly among the birds. What a magical experience!

My passengers come from all over the world and are all kinds of people, especially Europeans. The flight inspires in me a huge respect for nature and I can communicate this respect to my passengers. There are also people with disabilities and those who want to experience a great time in the sky with the birds before leaving this world. It is an overwhelming spiritual experience. The most beautiful thing is to fly in the heavens with the angels that are the birds.

When watching the video, it’s difficult to look away from the birds, moving with a powerful grace through the air, but don’t miss the absolute joy and astonishment on the faces of Moullec’s passengers. This is going right on my bucket list.

See also The Kid Should See This on Moullec’s efforts, the 2011 documentary Earthflight that features Moullec, and Winged Migration, a 2001 nature film that features lots of stunning flying-with-birds footage. (via @tcarmody)

From XKCD, a reminder that human spaceflight is older than we might think and human flight is more recent.

I am a sucker for these sorts of things. Perhaps my favorite is that Cleopatra lived closer to the Moon landing than she did to the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Or maybe it’s that Ralph Macchio is five years older now than Pat Morita was when he played Mr. Miyagi opposite Macchio in The Karate Kid.

See also Timeline Twins, Unlikely Simultaneous Historical Events, and The Great Span.

Yesterday a Southwest flight from NYC to Dallas experienced an in-flight engine explosion and had to make an emergency landing in Philadelphia. The explosion tore a hole in the fuselage and a passenger started to get sucked out of the hole before being pulled back in (she subsequently died). As Wired’s Jack Stewart notes in an informative piece about how emergencies like this are handled, the plane’s pilot sounded remarkably calm in her communications with air traffic control:

The pilots don’t reach out to air traffic control until that descent is underway. “Something we teach students from day one is aviate, navigate, communicate — in that order,” says Brian Strzempkowski, who trains pilots at Ohio State University’s Center for Aviation Studies.

“They’d say mayday three times, say their call sign, engine failure, descending to 10,000 on heading of XYZ,” says Moss. The pilot, air traffic controllers, and an airline dispatch unit work to find the best airport for an emergency landing. In less critical circumstances, it may be better to fly a little farther to a larger airfield with more facilities, but in extreme emergencies — such as this one — the pilot can ask for priority, and the controllers will clear the path for her to land at the closest runway, in any direction.

As terrifying as this looks, the pilot talking to air traffic control sounded remarkably calm. “We have a part of the aircraft missing, so we’re going to need to slow down a bit,” she said.

You can listen to the air traffic control audio here:

The pilot, Tammie Jo Shults, was a Navy fighter pilot, so that explains some of her chill. And Neil Armstrong’s combat experience in the Navy surely contributed to his calmness when he took manual control to steer the LM around an unsuitable landing site w/ very little fuel left while trying to land on the surface of the dang Moon with unknown alarms going off — you can read all about it here and listen to Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Mission Control discussing the whole thing here as if they’re trying to decide on a lunch place.

But the Navy angle is not the whole story. I’ve talked a bit before about my dad, who was a working pilot when I was a kid. He was sometimes not the most relaxed person on the ground, but at the controls of a plane, he was always calm and collected.

It was a fine day when we set out but as we neared our destination, the weather turned dark. You could see the storm coming from miles away and we raced it to the airport. The wind had really picked up as we made our first approach to land; I don’t know what the windspeed was, but it was buffeting us around pretty good. About 50 feet off the ground, the wind slammed the plane downwards, dropping a dozen feet in half a second. In a calm voice, my dad said, “we’d better go around and try this again”.

The storm was nearly on top of us as we looped around to try a second time. It was around this time he announced, even more calmly, that we were “running a little low” on fuel. Nothing serious, you understand. Just “a little low”.

How these pilots talk is not an accident. That characterless voice emanating from the flight deck during the boarding process telling you about your destination’s weather sounds conversationally beige…until something like losing an engine at 30,000 feet happens and that exact same voice, and the demeanor that goes with it, takes on a razor’s edge of magnificent competence and steadiness and even heroism.

I always feel a little silly when I click through to watch videos with titles like “Plane Miraculously Flies To Safety After Sudden Engine Failure”, like I’m indulging in clickbait, a sugary online snack when I’m supposed to be consuming healthier fare. But my dad was a pilot when I was a kid, so I will watch any flying video that comes along (along with 35 minutes of “related videos” on YouTube…send help!)

But this one in particular is worth a look because all the drama lasts for less than a minute and the first person view from the camera (which is mounted on the pilot’s head) puts you right into the cockpit.1 One of the coolest things about wearable cameras like the GoPro is that ability to put the viewer into the action, to create a visceral sense of empathy with that person doing that thing. That pilot’s eyes are our eyes for those 60 seconds. You see the engine fail. Your arm reaches out to the controls and attempts to address the problem. You pull the plane up into a glide. You look around for somewhere to ditch. Ah, there. You turn the plane. You keep trying to restart the engine… I don’t know about you, but my palms were pretty sweaty by the time that video was over.

I’ve been paying way more attention to the different ways in which filmmakers use the camera to create this sort of empathy since watching Evan Puschak’s video on how David Fincher’s camera hijacks your eyes. The first-person camera view, where the camera moves as if it were swiveling around on a real person’s neck, is a particularly effective technique. Even if the scene in this video weren’t real, it would be difficult to convince your brain otherwise given your vantage point. (via digg)

Design studio Haptic Lab just launched a Kickstarter campaign for The Flying Martha Ornithopter, a rubber-band-powered passenger pigeon that flies by flapping its paper wings.

Made in the likeness of the extinct passenger pigeon, the Flying Martha is symbolic of humanity’s role in a rapidly changing world. The passenger pigeon was once the most numerous bird species on the planet, with an estimated population of 3-5 billion birds. No one could have imagined that the entire species would disappear in one human lifetime. Extinctions will become more commonplace in the next century as the climate crisis deepens. But we’re still hopeful that a balance is possible; the passenger pigeon is a symbol of that hope.

The Flying Martha, named after the last known passenger pigeon, has wings made of mulberry paper, a wingspan of 16 inches, and weighs only 12.5 grams. I ordered one, ostensibly for my kids, but who am I kidding here…I’m really looking forward to playing with this.

Sunday at The Chicago Air and Water Show, a Blue Angels combat jet flew very low past an unsuspecting crowd and surprised the bejeezus out of some folks. It’s worth watching this video on a large screen multiple times while focusing on the reaction of a different person each time. You can see how low and fast the plane was flying from another angle. They also flew between the buildings downtown.

On March 8-9, 2016, a total solar eclipse swept across the Pacific Ocean for more than 5 hours. About a year before the eclipse, Hayden Planetarium astronomer Joe Rao realized Alaska Airlines flight 870 from Anchorage to Honolulu would pass right through the path of totality…but 25 minutes too early. Rao called the airline and convinced them to shift the flight time.

Alaska’s fleet director, Captain Brian Holm, reviewed the proposed flight path and possible in-route changes to optimize for the eclipse. The schedule planning team pushed back the departure time by 25 minutes, to 2 p.m.

On the day of the flight, Dispatch will develop the specific flight plan, to find the most efficient route and account for weather and wind. Maintenance and maintenance control will help make sure the plane is ready to go — they even washed all the windows on the right side of the plane.

Captain Hal Andersen also coordinated with Oceanic Air Traffic Control, to make them aware that the flight might require a few more tactical changes then normal.

“The key to success here is meeting some very tight time constraints — specific latitudes and longitudes over the ocean,” Andersen said. “With the flight management computer, it’s a pretty easy challenge, but it’s something we need to pay very close attention to. We don’t want to be too far ahead or too far behind schedule.”

The video was shot by a very excited Mike Kentrianakis of the American Astronomical Society, who has witnessed 20 solar eclipses during his lifetime.

July 11, 2010. That was the eclipse over Easter Island, the one for which hotel room rates were so high that there was no way Kentrianakis could afford it. Instead, he considered attempting a trip to Argentina, where experts predicted there was a 5 percent chance of clear skies. His wife at the time, Olga, urged him not to go — it’s not worth the expense, she insisted. Reluctantly, Kentrianakis stayed home.

“It was the beginning of the end for us,” Kentrianakis says. There were problems in the marriage before that episode, “but it affected me that I felt that she didn’t really appreciate what I loved.” They were divorced the following year.

Kentrianakis doesn’t like to dwell on this, or the other things he’s given up to chase eclipses. He knows his bosses grumbled about the missed days of work. Friends raise their eyebrows at the extremes to which he goes. He’s unwilling to admit how much he’s spent on his obsession.

“There is a trade-off for everything, for what somebody wants,” he says.

A camera on the Deep Space Climate Observatory satellite captured the eclipse’s shadow as it moved across the Earth:

For this year’s eclipse, Alaska Airlines is doing a special charter flight for astronomy nerds and eclipse chasers. Depending on how this eclipse goes, seeing an eclipse from an airplane might be on my bucket list for next time. (via @coudal)

Sales Wick is a pilot for SWISS and while working an overnight flight from Zurich to Sao Paulo, he filmed the first segment of the flight from basically the dashboard of the plane and made a timelapse video out of it. At that altitude, without a lot of light and atmospheric interference, the Milky Way is super vivid.

Just as the bright city lights are vanishing behind us, the Milky Way starts to become clearly visible up ahead. Its now us, pacing at almost the speed of sound along the invisible highway and the pitch-black night sky above this surreal landscape. Ahead of us are another eight hours flight time, but we already stopped counting the shooting stars. And we got already to a few hundred.

I watched this twice already, once to specifically pay attention to all the passing airplanes. The sky is surprisingly busy, even at that hour. (via @ozans)

Update: Several people asked if this was fake or digitally composited (the Milky Way and ground footage shot separately then edited together). I don’t know for sure, but I doubt it. The answer lies in the camera Wick used to shoot this, the Sony a7S. It’s really good in low-light conditions, better than many more expensive professional cameras even. As the last bit of this Vox video explains, the camera is so good in low light that the BBC used it to capture some night scenes for Planet Earth II. Here’s a screen-capped comparison at 6400 ISO from that video:

And the full scene at 32000 ISO:

That’s pretty amazing, right? Wick himself says on his site:

I had to take many attempts and a lot of trying to figure it out. Basically the challenge is to keep shutter speed as fast as possible in order to get razor sharp images. While you can use the 500 or 600 rule on ground this doesn’t work out the same way while being up in the sky. Well of course basically it does if you dont fly perpendicular to the movement of the night sky but even if its really smooth there are usually some light movements of the aircraft. So depending on the focal length of your lense you can get exposure times between 15” to 1”. Thats why you will need a camera that can handle high iso. Thats where the A7s comes into play and of course a ver fast lense. The rest is a good mounting and some luck. Last but not least you need to keep the flight deck as dark as possible to get the least reflections…and the rest is magic ;)

Yesterday, a video of a man dragged from an overbooked United flight because he wouldn’t give up his seat went viral. Public reaction to the incident and United’s subsequent fumbling of the aftermath has resulted in UAL’s stock falling several percentage points this morning:

The stock has rebounded slightly this afternoon and will probably fully recover within the next few weeks.

Also yesterday, a man walked into a San Bernardino elementary school and killed a teacher (his estranged wife) and an 8-year-old boy before shooting himself. The story has received very light national coverage, particularly in comparison to the United story. In response, the stock prices of gun companies were up a few percent this morning (top: American Outdoor Brands Corp which owns Smith & Wesson; bottom: Sturm, Ruger & Company):

This follows a familiar pattern of gun stock prices rising after shootings; Smith & Wesson’s stock price rose almost 9% after the mass shooting in Orlando last year.

Update: It took about three and a half weeks, but on May 2, United’s stock had regained all of the value “lost” due to the incident and subsequent PR blunders. As of this writing (May 3 at 12:41 PM ET), UAL is actually up about 3.5% from the closing price before the incident.

Older posts

Stay Connected