p63

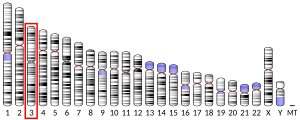

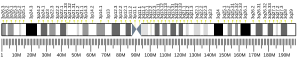

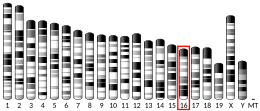

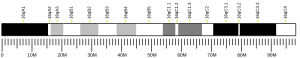

p63は、ヒトではTP63(p63)遺伝子にコードされるタンパク質である[5][6][7][8]。

TP63遺伝子はp53がん抑制遺伝子の発見から約20年後に発見された遺伝子で、構造的類似性をもとにp73とともにp53遺伝子ファミリーを構成する[9]。p53、p63、p73の系統学的解析からは、このファミリーの中ではp63が最初に存在し、そこからp53とp73が進化したことが示唆されている[10]。

機能

[編集]p63はp53ファミリーの転写因子である。p63-/-マウスでは四肢の欠損のほか、歯や乳腺など、間葉と上皮の相互作用によって発生が行われる組織の欠損を含む、いくつかの発生上の欠陥がみられる。TP63遺伝子からは代替的プロモーターによって2つの主要なアイソフォーム(TAp63とΔNp63)が産生される。ΔNp63は皮膚の発生や成体幹細胞/前駆細胞の調節など複数の機能に関与している[11]。TAp63の機能は主にアポトーシスに関するものに限定されており、卵母細胞の完全性の維持に機能していることが示されている[12]。また、TAp63が心臓発生[13]や早老[14]にも寄与していることが明らかにされている。

マウスではp63は膜タンパク質PERPの転写を担っており、皮膚の正常な発生に必要である。ヒトのがんにおいても、p63はp53とともにPERPの発現を調節している[15]。

卵母細胞の完全性

[編集]卵母細胞では、染色体が正しく整列していない細胞や、修復が不可能な染色体を有する細胞をアポトーシスによって除去する独特な品質管理システムが存在する[16]。この監視システムは線虫やハエからヒトまで保存されており、p53ファミリーのタンパク質、特に脊椎動物ではp63タンパク質が中核的役割を果たしている[16]。減数分裂時に相同組換え過程によって形成されたDNA二本鎖切断を修復できない卵母細胞は、p63と関連したアポトーシスによって除去される[16]。

臨床的意義

[編集]TP63遺伝子には、疾患の原因となる変異が少なくとも42種類発見されている[17]。TP63の変異は口唇口蓋裂が特徴となる、いくつかの奇形症候群の原因となっている[18]。TP63の変異は、AEC症候群(ankyloblepharon-ectodermal defects-cleft lip/palate syndrome)、ADULT症候群(acro-dermal-ungual-lacrimal-tooth syndrome)、EEC症候群3型(ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft lip/palate syndrome 3)、四肢-乳房症候群(limb-mammary syndrome)、非症候群性口唇裂口蓋裂8型(isolated cleft lip/palate; orofacial cleft 8)と関連している[19]。近年、EEC症候群患者由来のiPS細胞を用いた実験によって、TP63の変異による上皮運命決定の欠陥が低分子化合物によって部分的にレスキューされる可能性が示されている[20]。

分子機構

[編集]転写因子p63は、上皮のケラチノサイトの増殖と分化の重要な調節因子である。近年の研究では、p63のDNA結合ドメインにヘテロ接合型変異を有するEEC症候群患者由来の皮膚ケラチノサイトをモデルとして用いて、全体的な遺伝子調節変化の解析が行われている。p63変異ケラチノサイトでは、上皮遺伝子のダウンレギュレーションや非上皮遺伝子のアップレギュレーションなど、上皮細胞のアイデンティティが損なわれていた。さらに、p63結合の喪失や活発なエンハンサーの喪失がゲノムワイドに生じていた[21]。また、マルチオミクスアプローチによって、p63やCTCFによるDNAループの形成機能の調節不全が疾患の新たな機序として明らかにされている。上皮ケラチノサイトでは、上皮遺伝子に近接するいくつかの遺伝子座は、CTCFによるクロマチン相互作用の内部で制御性クロマチンハブへと組織化されている。こうしたハブには連結された複数のDNAループが含まれており、その形成には静的なCTCFの結合を必要とするだけでなく、転写活性をもたらすためにp63のような細胞種特異的転写因子の結合も必要となる。この研究で提唱されたモデルでは、転写が活発に行われるDNAループの形成にp63が必要不可欠である可能性が示唆されている[22]。

診断における利用

[編集]

p63に対する免疫染色は、頭頸部扁平上皮癌や、前立腺癌と良性前立腺組織との鑑別に有用である[23]。正常な前立腺では基底細胞の核がp63で染色されるのに対し、前立腺癌は基底細胞を欠くため染色されない[24]。また、p63は肺癌において低分化扁平上皮癌と小細胞癌や腺癌との鑑別にも有用である。低分化扁平上皮癌は抗p63抗体によって強く染色されるが、小細胞癌や腺癌は染色されない[25]。

筋分化した細胞では細胞質での染色が観察される[26]。

相互作用

[編集]p63はHNRNPABと相互作用することが示されている[27]。また、p63はエンハンサーを介してIRF6の転写を活性化する[18]。

調節

[編集]p63の発現がmiR-203によって調節されており[28][29]、またタンパク質レベルでもUSP28によって調節されていることを示すエビデンスが得られている[30][31]。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000073282 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022510 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27-29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities”. Molecular Cell 2 (3): 305–16. (September 1998). doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80275-0. PMID 9774969.

- ^ “Cloning and functional analysis of human p51, which structurally and functionally resembles p53”. Nature Medicine 4 (7): 839–43. (July 1998). doi:10.1038/nm0798-839. PMID 9662378.

- ^ “NBP is the p53 homolog p63”. Carcinogenesis 22 (2): 215–9. (February 2001). doi:10.1093/carcin/22.2.215. PMID 11181441.

- ^ “p53CP is p51/p63, the third member of the p53 gene family: partial purification and characterization”. Carcinogenesis 22 (2): 295–300. (February 2001). doi:10.1093/carcin/22.2.295. PMID 11181451.

- ^ “DeltaNp63alpha and TAp63alpha regulate transcription of genes with distinct biological functions in cancer and development”. Cancer Research 63 (10): 2351–7. (May 2003). PMID 12750249.

- ^ “Dedicated protection for the female germline”. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 8 (1): 4–5. (January 2007). doi:10.1038/nrm2091.

- ^ “p63 in epithelial survival, germ cell surveillance, and neoplasia”. Annual Review of Pathology 5: 349–71. (2010). doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102117. PMID 20078223.

- ^ “DNA damage in oocytes induces a switch of the quality control factor TAp63α from dimer to tetramer”. Cell 144 (4): 566–76. (February 2011). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.013. PMC 3087504. PMID 21335238.

- ^ “TAp63 is important for cardiac differentiation of embryonic stem cells and heart development”. Stem Cells 29 (11): 1672–83. (November 2011). doi:10.1002/stem.723. hdl:2066/97162. PMID 21898690. オリジナルの2014-08-08時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ “TAp63 prevents premature aging by promoting adult stem cell maintenance”. Cell Stem Cell 5 (1): 64–75. (July 2009). doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.003. PMC 3418222. PMID 19570515.

- ^ “PERP-ing into diverse mechanisms of cancer pathogenesis: Regulation and role of the p53/p63 effector PERP”. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 1874 (1): 188393. (Dec 2020). doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188393. PMID 32679166.

- ^ a b c Gebel, Jakob; Tuppi, Marcel; Sänger, Nicole; Schumacher, Björn; Dötsch, Volker (2020-12-03). “DNA Damaged Induced Cell Death in Oocytes”. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 25 (23): 5714. doi:10.3390/molecules25235714. ISSN 1420-3049. PMC 7730327. PMID 33287328.

- ^ “Refinement of evolutionary medicine predictions based on clinical evidence for the manifestations of Mendelian diseases”. Scientific Reports 9 (1): 18577. (December 2019). Bibcode: 2019NatSR...918577S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54976-4. PMC 6901466. PMID 31819097.

- ^ a b “Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences”. Nature Reviews. Genetics 12 (3): 167–78. (March 2011). doi:10.1038/nrg2933. PMC 3086810. PMID 21331089.

- ^ “GRJ TP63関連疾患”. grj.umin.jp. 2024年6月8日閲覧。

- ^ “Impaired epithelial differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells from ectodermal dysplasia-related patients is rescued by the small compound APR-246/PRIMA-1MET”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110 (6): 2152–6. (February 2013). Bibcode: 2013PNAS..110.2152S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201753109. PMC 3568301. PMID 23355677.

- ^ “Mutant p63 affects epidermal cell identity through rewiring the enhancer landscape”. Cell Reports 25 (12): 3490–503. (December 2018). doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.039. hdl:2066/200262. PMID 30566872.

- ^ “p63 cooperates with CTCF to modulate chromatin architecture in skin keratinocytes”. Epigenetics & Chromatin 12 (1): 31. (June 2019). doi:10.1186/s13072-019-0280-y. PMC 6547520. PMID 31164150.

- ^ “p63 as a complementary basal cell specific marker to high molecular weight-cytokeratin in distinguishing prostatic carcinoma from benign prostatic lesions”. The Medical Journal of Malaysia 62 (1): 36–9. (March 2007). PMID 17682568.

- ^ “Immunohistochemical antibody cocktail staining (p63/HMWCK/AMACR) of ductal adenocarcinoma and Gleason pattern 4 cribriform and noncribriform acinar adenocarcinomas of the prostate”. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology 31 (6): 889–94. (June 2007). doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000213447.16526.7f. PMID 17527076.

- ^ “Distinction of pulmonary small cell carcinoma from poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical approach”. Modern Pathology 18 (1): 111–8. (January 2005). doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800251. PMID 15309021.

- ^ Martin SE, Temm CJ, Goheen MP, Ulbright TM, Hattab EM (2011). “Cytoplasmic p63 immunohistochemistry is a useful marker for muscle differentiation: an immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopic study.”. Mod Pathol 24 (10): 1320–6. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2011.89. PMID 21623385.

- ^ “P63 alpha mutations lead to aberrant splicing of keratinocyte growth factor receptor in the Hay-Wells syndrome”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (26): 23906–14. (June 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M300746200. PMID 12692135.

- ^ “A skin microRNA promotes differentiation by repressing 'stemness'”. Nature 452 (7184): 225–9. (March 2008). Bibcode: 2008Natur.452..225Y. doi:10.1038/nature06642. PMC 4346711. PMID 18311128.

- ^ “miRNAs, 'stemness' and skin”. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 33 (12): 583–91. (December 2008). doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2008.09.002. PMID 18848452. オリジナルの2013-04-21時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Prieto-Garcia, C.; Hartmann, O; Reissland, M.; Braun, F.; Fischer, T.; Walz, S.; Fischer, A.; Calzado, M. et al. (Jun 2019). “The USP28-∆Np63 axis is a vulnerability of squamous tumours” (英語). bioRxiv: 683508. doi:10.1101/683508.

- ^ “Maintaining protein stability of ∆Np63 via USP28 is required by squamous cancer cells”. EMBO Molecular Medicine 12 (4): e11101. (March 2020). doi:10.15252/emmm.201911101. PMC 7136964. PMID 32128997.

関連文献

[編集]- “p63”. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 34 (1): 6–9. (January 2002). doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00086-3. PMID 11733180.

- “Mutations in the p53 homolog p63: allele-specific developmental syndromes in humans”. Trends in Molecular Medicine 8 (3): 133–9. (March 2002). doi:10.1016/S1471-4914(01)02260-2. PMID 11879774.

- “Splitting p63”. American Journal of Human Genetics 71 (1): 1–13. (July 2002). doi:10.1086/341450. PMC 384966. PMID 12037717.

- “P63 gene mutations and human developmental syndromes”. American Journal of Medical Genetics 112 (3): 284–90. (October 2002). doi:10.1002/ajmg.10778. PMID 12357472.

- “Neuronal survival and p73/p63/p53: a family affair”. The Neuroscientist 10 (5): 443–55. (October 2004). doi:10.1177/1073858404263456. PMID 15359011.

- “The soluble p51 protein in cancer diagnosis, prevention and therapy”. In Vivo 19 (3): 591–8. (2005). PMID 15875781.

- “Dlx genes, p63, and ectodermal dysplasias”. Birth Defects Research. Part C, Embryo Today 75 (3): 163–71. (September 2005). doi:10.1002/bdrc.20047. PMC 1317295. PMID 16187309.

- “p63 and epithelial biology”. Experimental Cell Research 312 (6): 695–706. (April 2006). doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.028. PMID 16406339.

- “ΔNp63 is an ectodermal gatekeeper of epidermal morphogenesis”. Cell Death and Differentiation 18 (5): 887–96. (May 2011). doi:10.1038/cdd.2010.159. PMC 3131930. PMID 21127502.

関連項目

[編集]- AMACR - 前立腺癌のマーカーとなる他のタンパク質