- Early Modern, English, Seventeenth-Century British History and Culture, The English Civil War and Revolution, Diggers, Gerrard Winstanley, and 32 moreFeminist Theory, Women's Studies, Rhetoric, Shakespeare, Masculinities, Masculinity, Jacques Lacan, Slavoj Žižek, Early Modern Literature, Niccolò Machiavelli, Renaissance, Renaissance literature, Humanism, Tudor England, Bibliographic Research, Authoritarianism, Early Modern Britain, Machiavelli, Roman Republic, Republic of Letters (Early Modern History), Sigmund Freud, Utopian Studies, Psychoanalysis, Early Modern English drama, Ancient Music, Renaissance Humanism, Aristotelianism, Ancient Greek and Roman Theatre, Immanuel Kant, History of Physiognomy, Ancient Physiognomy, and Physiognomyedit

- The most plagiarized author in history.edit

Theoretically informed scholarship on early modern English utopian literature has largely focused on Marxist interpretation of these texts in an attempt to characterize them as proto- Marxist. The present volume instead focuses on... more

Theoretically informed scholarship on early modern English utopian literature has largely focused on Marxist interpretation of these texts in an attempt to characterize them as proto- Marxist. The present volume instead focuses on subjectivity in early modern English utopian writing by using these texts as case studies to explore intersections of the thought of Jacques Lacan and Michel Foucault. Both Lacan and Foucault moved back and forth between structuralist and post-structuralist intellectual trends and ultimately both defy strict categorization into either camp. Although numerous studies have appeared that compare Lacan’s and Foucault’s thought, there have been relatively few applications of their thought together onto literature. By applying the thought of both theorists, who were not literary critics, to readings of early modern English utopian literature, this study will, on the one hand, describe the formation of utopian subjectivity that is both psychoanalytically (Oedipal and pre-Oedipal) and socially constructed, and, on the other hand, demonstrate new ways in which the thought of Lacan and Foucault inform and complement each other when applied to literary texts. The utopian subject is a malleable subject, a subject whose linguistic, psychoanalytical subjectivity determines the extent to which environmental and social factors manifest in an identity that moves among Lacan’s Symbolic, Imaginary, and Real.

Chapter 10 from my book, which was rejected by a journal. It was subsequently plagiarized in a recent biography of Harrington.

Chapter 3 from my book, which was plagiarized by someone in Atlanta.

Chapter 11 from my book. I submitted this to LIT: Literature Interpretation Theory, but it was immediately rejected and given to someone else to steal.

Chapter 6 from my book.

Shit-faced Shakespeare provides an hour-long, significantly condensed version of one of Shakespeare's plays in which one of the actors has consumed a considerable amount of alcohol before the performance. The remaining performers attempt... more

Shit-faced Shakespeare provides an hour-long, significantly condensed version of one of Shakespeare's plays in which one of the actors has consumed a considerable amount of alcohol before the performance. The remaining performers attempt to stage the stripped-down version of the play while improvising responses and adjustments based on the drunken performer's antics. The show provided an hour of good dirty fun and highlighted the populist nature of American Shakespearean appropriation and commodification and the intersection of highbrow and lowbrow culture in American society. The final section of this review explores these aspects of Shakespearean appropriation through engagement with the writings of Antonin Artaud, Guy Debord, and Lawrence Levine on the theatre of cruelty, the society of the spectacle, and highbrow and lowbrow culture, respectively. Shit-faced Shakespeare has created versions of several of Shakespeare's plays, including Hamlet, Macbeth, and A Midsummer Night's Dream. On the night this reviewer attended, the Village Theatre presented the "shit-faced" version of Romeo and Juliet, in which the actor playing Romeo (Robert Hindsman) was the designated shit-faced performer. There were laughs aplenty and the show would be a delight for people with any level of familiarity with Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, or the theatre in general, including those who were "supposed to read" the play in high school. The auditorium sat a few hundred people in front of a thrust stage, with the show selling out several days before its presentation. Before the performance began, loud contemporary pop music blasted through the space. The audience was a diverse mix of ages and ethnicities, and some members looked and acted like they attended the performance to do their pre-drinking prior to going out to Atlanta's night clubs to get really shit-faced. Before the performance began, Rachel Frawley as Compere (master of ceremonies), dressed like a cross between a zombie showgirl and Dr. Frank-N-Furter from The Rocky Horror Picture Show, introduced the concept of the performance and handed out "toys"-including a small cymbal and mallet and a brass horn-that the audience members were supposed to sound when they wanted drunken Romeo to drink

Research Interests:

The commentaries on the sessions II and III focus on the ancient, early modern, and modern authors, figures, and texts to provide context to the ancient material Lacan only mentions in passing. Together these bring to bear contexts or... more

The commentaries on the sessions II and III focus on the ancient, early modern, and modern authors, figures, and texts to provide context to the ancient material Lacan only mentions in passing. Together these bring to bear contexts or backgrounds whose absence might restrict our understanding of these sessions.

Research Interests:

William Shakespeare’s Hamlet has become one of the most cited, appropriated, and referenced texts in the Western canon. This article examines an overlooked appropriation, the cult classic TV show Mystery Science Theater 3000’s episode... more

William Shakespeare’s Hamlet has become one of the most cited, appropriated,

and referenced texts in the Western canon. This article examines an

overlooked appropriation, the cult classic TV show Mystery Science Theater

3000’s episode entitled “Hamlet.” Popularly known as MST3K, the show

engaged in a very postmodern, metadiscourse by depicting characters watching

bad movies and making sarcastic comments about them for the viewer

at home. But in taking on this gloomy, black-and-white German-language

production of Hamlet, this MST3K episode poses important questions about

what constitutes a canonical work and how exactly a work becomes part of

a literary canon. Through an analysis of this episode of MST3K through the

perspectives of aesthetic and postmodern theory, this article suggests that this

appropriation of Hamlet ushers in a new type of canon initiation, and, in the

case of MST3K’s take on the play, presents what I would like to call a “postmodern

canon.”

and referenced texts in the Western canon. This article examines an

overlooked appropriation, the cult classic TV show Mystery Science Theater

3000’s episode entitled “Hamlet.” Popularly known as MST3K, the show

engaged in a very postmodern, metadiscourse by depicting characters watching

bad movies and making sarcastic comments about them for the viewer

at home. But in taking on this gloomy, black-and-white German-language

production of Hamlet, this MST3K episode poses important questions about

what constitutes a canonical work and how exactly a work becomes part of

a literary canon. Through an analysis of this episode of MST3K through the

perspectives of aesthetic and postmodern theory, this article suggests that this

appropriation of Hamlet ushers in a new type of canon initiation, and, in the

case of MST3K’s take on the play, presents what I would like to call a “postmodern

canon.”

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Physiognomy, the ancient pseudo-science of reading an individual’s outer appearance as a manifestation of their personality and psychological makeup, has garnered significant attention by scholars and critics, with several studies... more

Physiognomy, the ancient pseudo-science of reading an individual’s outer appearance as a manifestation of their personality and psychological makeup, has garnered significant attention by scholars and critics, with several studies exploring physiognomy’s prevalence in the ancient world. Tamsyn Barton (1994) argues that physiognomy should be central to any study of ancient science, and David Rohrbacher (2010) convincingly demonstrates that Roman biographers wrote for an audience they assumed familiar with physiognomic theory. Studies have also demonstrated that physiognomy was also an integral part of the Judeo-Christian intellectual tradition. For example, Mladen Popović (2007) comparatively traces physiognomic theory from ancient Jewish traditions through the Hellenistic period, and Chard Hartstock (2008) focuses specifically on the New Testament’s treatment of blindness to argue that physiognomy is both programmatic and problematic in the Luke-Acts. Building on the work of Popović and Hartstock, Mikeal Parsons (2011) argues that Luke characterizes people physiognomically in order to subvert them, while more recently Callie Callon (2019) has argued that physiognomy was used by early Christians as means of persuasion. Physiognomy, therefore, was an integral part of ancient psychological theory in both the pagan world and in Judaism and early Christianity.

Only four texts on physiognomy have survived from antiquity, but a recent collection edited by Simon Swain (2007) provides English translations of Arabic versions of texts by ancient physiognomers Polemon and Adamantius. Combined with the pseudo-Aristotelian text, Physiognomica, the corpus of ancient texts of physiognomy provide a small but relatively vivid glimpse into this ancient pseudo-science.

In this essay I argue that Roman Emperor, Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, has been subject to characterization based on physiognomic theories from the earliest depictions in ancient literary texts, statuary, and numismatics to Robert Graves’ two-volume fictionalized depiction and Derek Jacobi’s famous depiction in the BBC miniseries based on Graves’ books. Unlike other physiognomic characterizations of Roman emperors, however, those of Claudius have incorporated his physical disabilities into the physiognomical depictions. Through the perspective of Robert Garland (2010) and disability studies theorist, Tobin Siebers (2008; 2010), Claudius becomes a pagan foil for the numerous physiognomic descriptions found in the New Testament. Depictions of Claudius’ disability physiognomically, therefore, represents an anomaly both from the perspective of Julio-Claudian rule of Rome as well as in the context of Second Sophistic thought that influenced many of the writers of the New Testament. As Josiah Osgood (2011) has argued, depictions of Claudius have been subject to changing trends in historiography beginning with ancient texts and continuing through modern depictions. This paper builds on scholarship about physiognomy by focusing specifically on Claudius’ impairments and their ubiquitous treatment by ancient biographers to posit what I would like to call “physiognomic disability.”

Bibliography

Barton, Tamsyn. Power and Knowledge: Astrology, Physiognomics, and Medicine Under the Roman Empire. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Callon, Callie. Reading Bodies: Physiognomy as a Strategy of Persuasion in Early Christian Discourse. London: Bloomsbury, 2019.

Garland, Robert. The Eye of the Beholder: Deformity and Disability in the Graeco-Roman World. 2. ed. London: Bristol Classical Press, 2010.

Hartsock, Chad. Sight and Blindness in Luke-Acts: The Use of Physical Features in Characterization. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2008.

Osgood, Josiah. Claudius Caesar: Image and Power in the Early Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Parsons, Mikeal Carl. Body and Character in Luke and Acts: The Subversion of Physiognomy in Early Christianity. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 2011.

Popović, Mladen. Reading the Human Body: Physiognomics and Astrology in the Dead Sea Scrolls and Hellenistic-Early Roman Period Judaism. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Rohrbacher, David. “Physiognomics in Imperial Latin Biography.” Classical Antiquity 29, no. 1 (2010): 92–116.

Siebers, Tobin. Disability Aesthetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010.

———. Disability Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008.

Swain, Simon, ed. Seeing the Face, Seeing the Soul: Polemon’s Physiognomy from Classical Antiquity to Medieval Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Only four texts on physiognomy have survived from antiquity, but a recent collection edited by Simon Swain (2007) provides English translations of Arabic versions of texts by ancient physiognomers Polemon and Adamantius. Combined with the pseudo-Aristotelian text, Physiognomica, the corpus of ancient texts of physiognomy provide a small but relatively vivid glimpse into this ancient pseudo-science.

In this essay I argue that Roman Emperor, Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, has been subject to characterization based on physiognomic theories from the earliest depictions in ancient literary texts, statuary, and numismatics to Robert Graves’ two-volume fictionalized depiction and Derek Jacobi’s famous depiction in the BBC miniseries based on Graves’ books. Unlike other physiognomic characterizations of Roman emperors, however, those of Claudius have incorporated his physical disabilities into the physiognomical depictions. Through the perspective of Robert Garland (2010) and disability studies theorist, Tobin Siebers (2008; 2010), Claudius becomes a pagan foil for the numerous physiognomic descriptions found in the New Testament. Depictions of Claudius’ disability physiognomically, therefore, represents an anomaly both from the perspective of Julio-Claudian rule of Rome as well as in the context of Second Sophistic thought that influenced many of the writers of the New Testament. As Josiah Osgood (2011) has argued, depictions of Claudius have been subject to changing trends in historiography beginning with ancient texts and continuing through modern depictions. This paper builds on scholarship about physiognomy by focusing specifically on Claudius’ impairments and their ubiquitous treatment by ancient biographers to posit what I would like to call “physiognomic disability.”

Bibliography

Barton, Tamsyn. Power and Knowledge: Astrology, Physiognomics, and Medicine Under the Roman Empire. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Callon, Callie. Reading Bodies: Physiognomy as a Strategy of Persuasion in Early Christian Discourse. London: Bloomsbury, 2019.

Garland, Robert. The Eye of the Beholder: Deformity and Disability in the Graeco-Roman World. 2. ed. London: Bristol Classical Press, 2010.

Hartsock, Chad. Sight and Blindness in Luke-Acts: The Use of Physical Features in Characterization. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2008.

Osgood, Josiah. Claudius Caesar: Image and Power in the Early Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Parsons, Mikeal Carl. Body and Character in Luke and Acts: The Subversion of Physiognomy in Early Christianity. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 2011.

Popović, Mladen. Reading the Human Body: Physiognomics and Astrology in the Dead Sea Scrolls and Hellenistic-Early Roman Period Judaism. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Rohrbacher, David. “Physiognomics in Imperial Latin Biography.” Classical Antiquity 29, no. 1 (2010): 92–116.

Siebers, Tobin. Disability Aesthetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010.

———. Disability Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008.

Swain, Simon, ed. Seeing the Face, Seeing the Soul: Polemon’s Physiognomy from Classical Antiquity to Medieval Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Although primarily known for his agrarian utopian text, The Commonwealth of Oceana, Harrington also wrote a translation of parts of Virgil’s Aeneid, which critics have noted for its Royalist overtones. The physical presentation and... more

Although primarily known for his agrarian utopian text, The Commonwealth of Oceana, Harrington also wrote a translation of parts of Virgil’s Aeneid, which critics have noted for its Royalist overtones. The physical presentation and paratexts of Harrington’s translations, however, have not received critical attention. This essay will analyze these aspects of the two texts constituting Harrington’s partial translation of the Aeneid to argue that the decision to create and have printed a translation of this epic poem make as much of a political statement as the translation decisions involved in rendering the text into English. Harrington’s translation of Virgil, therefore, serves as a vehicle for Harrington’s political agenda through the use of bibliographic and paratextual elements that supersede the translated, textual, content of these two printed texts.

Hans Holbein the Younger’s (1497–1543) grotesque 1515 illustrations for Desiderius Erasmus’s (1467-1536) Moriae Encomium, or Praise of Folly appear to merely illustrate particular moments in the Moriae, but upon closer examination, facial... more

Hans Holbein the Younger’s (1497–1543) grotesque 1515 illustrations for Desiderius Erasmus’s (1467-1536) Moriae Encomium, or Praise of Folly appear to merely illustrate particular moments in the Moriae, but upon closer examination, facial features and body types reflect the ancient belief in physiognomy, the belief that outward appearance reflected inner qualities. Using Emanuel Levinas’ (1906-1995) ethical and phenomenological construct, the “face-to-face encounter,” this essay demonstrates how Holbein’s illustrations highlight the complicated ethical underpinnings of Erasmus’ through their inconsistent and contradictory relevance to the text. Holbein’s illustrations, therefore, add a meta-discursive dimension to Erasmus’ critique of humanistic intellectual history, and the Moriae and Holbein’s illustrations together demonstrate the transhistoricity of Levinasian ethics.

Although many studies have analyzed the prevalence of physiognomic thought in the New Testament, these studies have limited their focus to textual analysis of the Greek New Testament and other early Christian writings. In particular, some... more

Although many studies have analyzed the prevalence of physiognomic thought in the New Testament, these studies have limited their focus to textual analysis of the Greek New Testament and other early Christian writings. In particular, some studies have analyzed physiognomic thought in the Pauline epistles and the book of Acts, and some have focused on the physiognomy of textual descriptions of Paul himself. This paper will expand on these studies to argue that artistic depictions of the Apostle Paul also reflect a belief in physiognomy; Rembrandt, Caravaggio, and Michelangelo created depictions of Paul, and I would like to argue that these representations present Paul through the perspective of physiognomic thought. Although an ancient pseudo-science, physiognomy was still popular in the Renaissance, and as a favorite subject for visual art, the Apostle Paul falls victim to such attempts to characterize an individual’s psychological makeup by analyzing outer appearance. I am following the lead of Avigdor Posèq, who in a 2006 article lucidly demonstrates Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s interest in the revival of physiognomic thought with the 1586 publication of Giovanni Battista Della Porta’s text on physiognomy.1

Numerous critics have written on physiognomic descriptions in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales by exploring such descriptions of Thopas, the Miller, the Friar, the Wife of Bath, and the Summoner. In this paper, I will extend these physiognomic... more

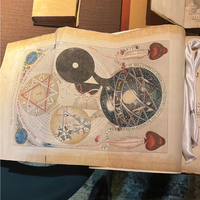

Numerous critics have written on physiognomic descriptions in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales by exploring such descriptions of Thopas, the Miller, the Friar, the Wife of Bath, and the Summoner. In this paper, I will extend these physiognomic readings to the illustrations in the Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript and in the Kelmscott Chaucer. The illustrations for the Ellesmere Chaucer largely follow the medieval physiognomy established by the Secretum Secretorum, and as Lynn Thorndyke observed, Michael Scot’s (1175 – c. 1232) Liber physiognomiae was immensely popular in the court of Emperor Frederick II. Physiognomy, therefore, was a thriving medieval intellectual tradition with which Chaucer and the illustrator of the Ellesmere manuscript would have been familiar.

Published by William Morris’ (1834-1896) Kelmscott Press, the Kelmscott Chaucer (1896) contains 87 illustrations by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898). I would like to suggest that Burne-Jones followed the physiognomic models established by Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741-1801), who revitalized Western interest in physiognomy after it had been dormant in the wake of seventeenth-century rationalism. Lavater’s writings on physiognomy were immensely popular and successful and were translated into every European language with numerous editions appearing throughout the nineteenth century. This suggests that physiognomy was as popular during Burne-Jones’ lifetime as it was during Scot’s and Chaucer’s.

In this essay, I will compare the illustrations for the Ellesmere manuscript and the Kelmscott edition to argue that physiognomy moved from text to illustration for both sets of illustrations. Furthermore, comparing these illustrators’ use of physiognomy reveals in the illustrators’ physiognomic consciousness a sensitivity to the philosophical debates concerning ontology, metaphysics, and the mind/body distinction contemporary to them. Although a pseudo-science, physiognomy, therefore, serves as a cultural and intellectual barometer through which we may better understand the nature of reading and interpretation.

Published by William Morris’ (1834-1896) Kelmscott Press, the Kelmscott Chaucer (1896) contains 87 illustrations by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898). I would like to suggest that Burne-Jones followed the physiognomic models established by Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741-1801), who revitalized Western interest in physiognomy after it had been dormant in the wake of seventeenth-century rationalism. Lavater’s writings on physiognomy were immensely popular and successful and were translated into every European language with numerous editions appearing throughout the nineteenth century. This suggests that physiognomy was as popular during Burne-Jones’ lifetime as it was during Scot’s and Chaucer’s.

In this essay, I will compare the illustrations for the Ellesmere manuscript and the Kelmscott edition to argue that physiognomy moved from text to illustration for both sets of illustrations. Furthermore, comparing these illustrators’ use of physiognomy reveals in the illustrators’ physiognomic consciousness a sensitivity to the philosophical debates concerning ontology, metaphysics, and the mind/body distinction contemporary to them. Although a pseudo-science, physiognomy, therefore, serves as a cultural and intellectual barometer through which we may better understand the nature of reading and interpretation.

This essay is about two kinds of reading: physiognomy and hermeneutic phenomenology. Physiognomy is the pseudo-science of reading an individual’s outer appearance, behaviour, and movement to determine inner character and psychology. In... more

This essay is about two kinds of reading: physiognomy and hermeneutic phenomenology. Physiognomy is the pseudo-science of reading an individual’s outer appearance, behaviour, and movement to determine inner character and psychology. In the Western tradition of physiognomy, the earliest surviving texts on the subject date back to classical Athens. Physiognomy continued to attract attention throughout the Middle Ages and the early modern period, but it was Swiss author Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741-1801) who brought renewed attention to physiognomy through a series of fragmentary writings. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) knew Lavater and encouraged him to write about physiognomy; Richard Gray (2004) has characterized Goethe as the “father of modern physiognomics.”

Pioneered by Paul Ricoeur, hermeneutic phenomenology similarly attempts to understand and interpret subjective experience. The primary aim of this essay is to find conceptual intersections between Lavater’s physiognomics and Ricoeur’s hermeneutic phenomenology. To this end, the first part of this essay will provide close readings of Goethe’s literary works through the theoretical perspectives of Lavater and Ricoeur. In the second part of this essay, I will situate Lavater’s writings in the intellectual context of eighteenth-century philosophers Hume, Kant, and Hegel. In the final part of the essay, I will focus on Eugène Delacroix’s (1798-1863) physiognomic illustrations for his 1828 edition of Goethe’s Faust to argue that physiognomy is an important aspect of Goethe’s writings and aesthetics as well as an integral component to the afterlives and reception of his writings.

Pioneered by Paul Ricoeur, hermeneutic phenomenology similarly attempts to understand and interpret subjective experience. The primary aim of this essay is to find conceptual intersections between Lavater’s physiognomics and Ricoeur’s hermeneutic phenomenology. To this end, the first part of this essay will provide close readings of Goethe’s literary works through the theoretical perspectives of Lavater and Ricoeur. In the second part of this essay, I will situate Lavater’s writings in the intellectual context of eighteenth-century philosophers Hume, Kant, and Hegel. In the final part of the essay, I will focus on Eugène Delacroix’s (1798-1863) physiognomic illustrations for his 1828 edition of Goethe’s Faust to argue that physiognomy is an important aspect of Goethe’s writings and aesthetics as well as an integral component to the afterlives and reception of his writings.

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, was a pioneer in the seventeenth-century English print trade. Although preceded by numerous Englishwomen who wrote and published before her, Cavendish was the first woman in England who... more

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, was a pioneer in the seventeenth-century English print trade. Although preceded by numerous Englishwomen who wrote and published before her, Cavendish was the first woman in England who sought to establish herself as a published, professional writer. Bibliographically, Cavendish’s books are aesthetically impressive; D. F. McKenzie has labelled Cavendish’s printed texts as “interesting for their surface—they’re sumptuous, lavishly spaced, highly decorated folios printed in Great Primer or Double Pica on good paper.”1 In addition to their aesthetic appeal, Cavendish’s printed works reflect a deliberate use of the print medium to promote their author’s contributions in the fields of science, natural history, and literature, which of course had been dominated previously by men such as Francis Bacon, Robert Hooke, and Thomas Hobbes.

Cavendish’s bibliographic self-presentation manifests most prominently on the title pages of her printed works. Several of her books were printed in two or more editions with distinctly different titles, authorial attributions, and permutations of her name, Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. These variations often reflect the chaotic circumstances of Cavendish’s life, which included periods of exile during the English Civil War. In this essay, I demonstrate how Cavendish’s printed texts reflect her desire to become a respected member of the publishing community in Civil War-era England while simultaneously revealing the complicated and chaotic nature of the political lives of English nobles in the seventeenth century.

1 D. F. McKenzie, Making Meaning: “Printers of the Mind” and Other Essays, ed. Peter D. McDonald and Michael Felix Suarez (Amherst: University Of Massachusetts Press, 2002), 122.

Cavendish’s bibliographic self-presentation manifests most prominently on the title pages of her printed works. Several of her books were printed in two or more editions with distinctly different titles, authorial attributions, and permutations of her name, Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. These variations often reflect the chaotic circumstances of Cavendish’s life, which included periods of exile during the English Civil War. In this essay, I demonstrate how Cavendish’s printed texts reflect her desire to become a respected member of the publishing community in Civil War-era England while simultaneously revealing the complicated and chaotic nature of the political lives of English nobles in the seventeenth century.

1 D. F. McKenzie, Making Meaning: “Printers of the Mind” and Other Essays, ed. Peter D. McDonald and Michael Felix Suarez (Amherst: University Of Massachusetts Press, 2002), 122.

James Harrington’s The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656), depicts communist agrarian communist utopia with exhaustive detail of voting procedures, taxation, and other such administrative components of a society. But it is the text’s use of... more

James Harrington’s The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656), depicts communist agrarian communist utopia with exhaustive detail of voting procedures, taxation, and other such administrative components of a society. But it is the text’s use of wildly disparate document design that Harrington really presents his utopian vision. From varying font sizes and font types to intentionally inconsistent spacing and blocking, Harrington’s Oceana constitutes what I would like to call a “utopia of print,” that is, a utopia of complete lexicographical freedom in its physical manifestation. Print historians and bibliographical scholars have largely ignored Harrington and his Oceana, and in this paper I demonstrate how Oceana’s form works in tandem with its content to create a textual utopia whose form and content reflect Harrington’s republican sympathies during the English Civil War.

Research Interests:

Thomas More's Utopia continues to elicit scholarly interest and has retained a firm place in the literary canon and British literature survey courses. Originally printed in Latin in 1516, new translations appear regularly, and frequently... more

Thomas More's Utopia continues to elicit scholarly interest and has retained a firm place in the literary canon and British literature survey courses. Originally printed in Latin in 1516, new translations appear regularly, and frequently these translations reflect values altered by the ever-changing Western political climate. For instance, the new Penguin Classics edition of More's Utopia, translated and edited by luminary More scholar Dominic Baker-Smith, largely stays close to the spirit of earlier twentieth-century translations, but some of Baker-Smith's translation decisions reflect the contemporary political landscape of academia. In this essay I will compare several translations of More's Utopia to demonstrate the way in which English translations have changed over time. In particular, I will examine J.H. Hexter's translation for the Yale edition, the first modern edition and still an important version of the text, and explore subsequent translations of key Latin passages in the original. Indeed, even Robert Adams's relatively recent translation for the popular Norton edition contrasts greatly with Baker-Smith's new Penguin translation. In addition, I will look at a 1947 edition compiled by Mildred Campbell to demonstrate how she used gendered language in a manner similar to Hexter, Adams, and Baker-Smith. I argue that since the 1556 translation by Ralph Robynson, More's text has elicited a subjective reading experience that has resulted in subjective translation decisions. These decisions reflect unintentional consequences for More's text, and this aspect of its history and reception is what has kept Utopia an important text in higher education and part of the Western literary canon. Translation played a very prominent role in the Reformation. John Wycliffe translated the Vulgate Bible into English in the fourteenth century, but his translation did not find a widespread audience. Aided by the relatively recent appearance of the printing press in England in 1476, however, English scholar William Tyndale translated the Bible from Hebrew and Greek texts and, along with Martin Luther, advocated for widespread dissemination of scripture in vernacular languages. Such an aim amounted to heresy in the eyes of the Catholic Church, leading Thomas More to write, "Tyndale changed in his translation the common known words to the intent to

Research Interests:

This is a survey of British literature from the Anglo-Saxon period to the eighteenth century. Our reading and discussion will give some attention to biographical issues and the historical context of the works, but the primary focus will... more

This is a survey of British literature from the Anglo-Saxon period to the eighteenth century. Our reading and discussion will give some attention to biographical issues and the historical context of the works, but the primary focus will be on the works themselves. Poetry and drama will be the genres most frequently explored, but there will be some examination of prose fiction and non-fiction prose. We will examine Old, Middle, and Modern English literature, although all Old English texts and some Middle English texts will be in translation. British Literature I carries with it three credit hours. Learning Outcomes • Students will become familiar with a representative body of major early British literature. • Students will considerably improve skills in reading and understanding literature. • Students will considerably improve skills in discussing and writing about literature. Required Texts Abrams, M. H., and Stephen Greenblatt. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. New York: Norton, 2000. Volume 1. 7 th edition. ISBN: 978-0-393947-73-1.

Research Interests:

During this fellowship I would like to combine essays I have written and will write to complete a book manuscript about physiognomy in art and literature through the perspective of Emanuel Levinas’ phenomenological face-to-face construct.... more

During this fellowship I would like to combine essays I have written and will write to complete a book manuscript about physiognomy in art and literature through the perspective of Emanuel Levinas’ phenomenological face-to-face construct. This fellowship will enable me to complete a book that will make an original contribution to the current scholarly conversation about the ancient art of physiognomy. I am specifically interested in getting advice from the ACMRS press members about how to shape these essays into a publishable monograph. Image permissions are expensive, and I would like to get advice about how to navigate that aspect of publishing.

This is the dissertation I wrote at Georgia State University.

George Orwell's 1984 depicts a dystopian society that controls the actions of its citizens in addition to controlling the language spoken by them. The society overtly controls the continuously updated language referred to as Newspeak by... more

George Orwell's 1984 depicts a dystopian society that controls the actions of its citizens in addition to controlling the language spoken by them. The society overtly controls the continuously updated language referred to as Newspeak by employing citizens to literally rewrite history in the new statist language. The society controls its populace through enough visible surveillance and police presence to force its citizens to police and control themselves. This resembles Michel Foucault's panoptic model, which he applied to epistemological and phenomenological discourse systems in addition to his explication of Jeremy Bentham's writings. The government's control of language reflects Jacques Lacan's Symbolic domain, which he claims houses language and therefore serves as the locus for human subjectivity. This essay will merge the largely sociological theories of Foucault with the psychological paradigm of Jacques Lacan to argue that 1984's dystopian society relies on controlling its populace by controlling its language in addition to transforming every citizen into a self-policing panopticon who keep themselves under a constant, self-censoring and self-guiding gaze. Critics have largely compartmentalized Foucault and Lacan into their own mutually exclusive camps, and this essay will therefore demonstrate the cross compatibility of two of the most prominent French theorists.

Draft submitted June 2016.

This monograph seeks to understand the nature of subjectivity in early modern utopian literature by locating intersections between the thought of Jacques Lacan and Michel Foucault. By categorizing ten early modern utopian texts using... more

This monograph seeks to understand the nature of subjectivity in early modern utopian literature by locating intersections between the thought of Jacques Lacan and Michel Foucault. By categorizing ten early modern utopian texts using Lacan's tripartite model of subjectivity, the Symbolic, Imaginary, and Real, my monograph will demonstrate that the thought of Lacan, a structuralist, and Foucault, a post-structuralist, actually inform and complement each other, and that it is possible to define utopian subjectivity from both a psychoanalytical point of view (Lacan) as well as from a biopolitical, social-constructivist point of view (Foucault). I will specifically demonstrate that subjectivity can come about from an individual's impartial or non-existent indoctrination into Lacan's Symbolic Order, the order of language, which can then result in a socially constructed subjectivity, which ultimately results in what I am going to call the malleable subject. Using early modern utopian texts as case studies, I seek to demonstrate that utopian literature engages with this kind of malleable subjectivity.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II has justifiably attracted much gender-oriented scholarly attention because of its conspicuously homosocial relationship between Gaveston and King Edward. Edward dotes on Gaveston throughout the play, and... more

Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II has justifiably attracted much gender-oriented scholarly attention because of its conspicuously homosocial relationship between Gaveston and King Edward. Edward dotes on Gaveston throughout the play, and his obsession ultimately leads to his downfall. Coupled with Edward’s attraction to Gaveston is Edward’s oftentimes explicit rejection of Isabella. Medieval notions of the role of women tended to steer their sole purpose toward that of merely a maternal, child-bearing function. This would have been especially true for royalty, as there was always an anxiety over the production of a male heir. In this way Isabella represents what Julia Kristeva would call a “maternal body.”

In Powers of Horror, Kristeva develops a notion of abjection that states that subjective and group identity are constituted by rejecting any presence that threatens one’s own personal borders, with the main threat being the dependence on the maternal body. King Edward and his son both strenuously reject the maternal body in Isabella. When King Edward says to Isabella, “Fawn not on me, French strumpet; get thee gone,” (4.145) he is not merely freeing up his sexuality to more openly pursue some form of consummation with Gaveston; by contrast he is also widening the gap between the (to him) repressive presence of women and the repressive presence of the maternal Law under which he feels subservient. This is the same maternal Law that placed him in the position of King, a position he was not qualified for as Holinshed’s Chronicles of England display. Prince Edward only fully gains ultimate power when he sends his mother to the Tower in the closing lines of the play. He also expresses the potential for feeling pity for the mother he has just sentenced to prison, but by his final speech his authority has outshined any sympathy: “Could I have ruled thee then, as I do now, / Thou hadst not hatched this monstrous treachery” (25.96-7).

Through the rejection/abjection of Isabella, the King and Prince are implicitly rejecting matrilineal integrity. Subversive implications of the rejection of a Queen in a play produced during the reign of Elizabeth go deeper than merely calling into question Elizabeth’s right to rule as the single, “virgin” queen. They go right to the heart of societal stipulations that women must stay subservient to men, and that men must not engage in unnatural sexual acts. In Marlowe’s depiction of the homosocial bond between Edward and Gaveston (who never physically “consummate” this attraction) Marlowe unsexes both the sovereign Edward and his Queen and as such posits that only an unsexed or asexual ruler can effectively rule. By viewing Edward II through the perspective of Lacanian readings of Freud’s Oedipal complex and Julia Kristeva’s notion of abjection, I demonstrate in this essay Marlowe’s acute sensitivity towards both his own latent homosexuality (which, according to Foucault, was itself a kind of asexuality in this period) as well as the often hypocritical “virginal” asexuality of Queen Elizabeth.

In Powers of Horror, Kristeva develops a notion of abjection that states that subjective and group identity are constituted by rejecting any presence that threatens one’s own personal borders, with the main threat being the dependence on the maternal body. King Edward and his son both strenuously reject the maternal body in Isabella. When King Edward says to Isabella, “Fawn not on me, French strumpet; get thee gone,” (4.145) he is not merely freeing up his sexuality to more openly pursue some form of consummation with Gaveston; by contrast he is also widening the gap between the (to him) repressive presence of women and the repressive presence of the maternal Law under which he feels subservient. This is the same maternal Law that placed him in the position of King, a position he was not qualified for as Holinshed’s Chronicles of England display. Prince Edward only fully gains ultimate power when he sends his mother to the Tower in the closing lines of the play. He also expresses the potential for feeling pity for the mother he has just sentenced to prison, but by his final speech his authority has outshined any sympathy: “Could I have ruled thee then, as I do now, / Thou hadst not hatched this monstrous treachery” (25.96-7).

Through the rejection/abjection of Isabella, the King and Prince are implicitly rejecting matrilineal integrity. Subversive implications of the rejection of a Queen in a play produced during the reign of Elizabeth go deeper than merely calling into question Elizabeth’s right to rule as the single, “virgin” queen. They go right to the heart of societal stipulations that women must stay subservient to men, and that men must not engage in unnatural sexual acts. In Marlowe’s depiction of the homosocial bond between Edward and Gaveston (who never physically “consummate” this attraction) Marlowe unsexes both the sovereign Edward and his Queen and as such posits that only an unsexed or asexual ruler can effectively rule. By viewing Edward II through the perspective of Lacanian readings of Freud’s Oedipal complex and Julia Kristeva’s notion of abjection, I demonstrate in this essay Marlowe’s acute sensitivity towards both his own latent homosexuality (which, according to Foucault, was itself a kind of asexuality in this period) as well as the often hypocritical “virginal” asexuality of Queen Elizabeth.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Theoretically informed scholarship on early modern English utopian literature has largely focused on Marxist interpretation of these texts in an attempt to characterize them as proto- Marxist. The present volume instead focuses on... more

Theoretically informed scholarship on early modern English utopian literature has largely focused on Marxist interpretation of these texts in an attempt to characterize them as proto- Marxist. The present volume instead focuses on subjectivity in early modern English utopian writing by using these texts as case studies to explore intersections of the thought of Jacques Lacan and Michel Foucault. Both Lacan and Foucault moved back and forth between structuralist and post-structuralist intellectual trends and ultimately both defy strict categorization into either camp. Although numerous studies have appeared that compare Lacan’s and Foucault’s thought, there have been relatively few applications of their thought together onto literature. By applying the thought of both theorists, who were not literary critics, to readings of early modern English utopian literature, this study will, on the one hand, describe the formation of utopian subjectivity that is both psychoanalytically (Oedipal and pre-Oedipal) and socially constructed, and, on the other hand, demonstrate new ways in which the thought of Lacan and Foucault inform and complement each other when applied to literary texts. The utopian subject is a malleable subject, a subject whose linguistic, psychoanalytical subjectivity determines the extent to which environmental and social factors manifest in an identity that moves among Lacan’s Symbolic, Imaginary, and Real.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

The commentaries on sessions II and III focus on the ancient, early modern, and modern authors, figures, and texts to provide context to the ancient material Lacan only mentions in passing. Together these bring to bear contexts or... more

The commentaries on sessions II and III focus on the ancient, early modern, and modern authors, figures, and texts to provide context to the ancient material Lacan only mentions in passing. Together these bring to bear contexts or backgrounds whose absence might restrict our understanding of these sessions.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

A review of the Atlanta production of Romeo and Juliet by the Shit-faced Shakespeare company. Argues that the performance "highlighted the populist nature of American Shakespearean appropriation and commodification and the... more

A review of the Atlanta production of Romeo and Juliet by the Shit-faced Shakespeare company. Argues that the performance "highlighted the populist nature of American Shakespearean appropriation and commodification and the intersection of highbrow and lowbrow culture in American society" and "explores these aspects of Shakespearean appropriation through engagement with the writings of Antonin Artaud, Guy Debord, and Lawrence Levine on the theatre of cruelty, the society of the spectacle, and highbrow and lowbrow culture, respectively."

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests: Art and Literary studies

Although we know few details of his life, we do know that Francis Lodwick (1619–1694) played a prominent role in the seventeenth-century philosophical language movement, a movement that sought to create an a priori language, known in the... more

Although we know few details of his life, we do know that Francis Lodwick (1619–1694) played a prominent role in the seventeenth-century philosophical language movement, a movement that sought to create an a priori language, known in the seventeenth century as a “philosophical language.” Such an endeavor aimed for what might be called a linguistic utopia resulting from the creation of an auxiliary language similar to Esperanto, a universal language developed in the nineteenth century and still in use today. But Lodwick also wrote on topics other than language and linguistics, as is suggested by the title of a new collection of Lodwick’s writings, On Language, Theology, and Utopia. This edition updates the only other modern edition of Lodwick’s printed works, found in Vivian Salmon’s The Works of Francis Lodwick: A Study of His Writings in the Intellectual Context of the Seventeenth Century (1972). Edited by Felicity Henderson and William Poole, the current book provides a much neede...

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

... lifeless in that role. Ad-mittedly this postulate is merely intuitive at this stage, but it does not take either especially wide reading or unusual powers of perception to sense that there is indeed something in it. Eliot found in... more

... lifeless in that role. Ad-mittedly this postulate is merely intuitive at this stage, but it does not take either especially wide reading or unusual powers of perception to sense that there is indeed something in it. Eliot found in Hamlet ...