Fero is a new way to write fast, scalable, stateful services that are also very resilient to failures and a breeze to operate.

- Why: Simplicity, Speed and Scale

- Design: Cross-breed between Apache Kafka and Uber Ringpop

- Example: Quick Getting Started

- Differences with Kafka: Lighter, Application-Layer Sharding, Dynamic

- Performance: Faster than Kafka/Redis, Sub-Millisecond Latency

- Next Steps & Contributing: Monitoring Tools

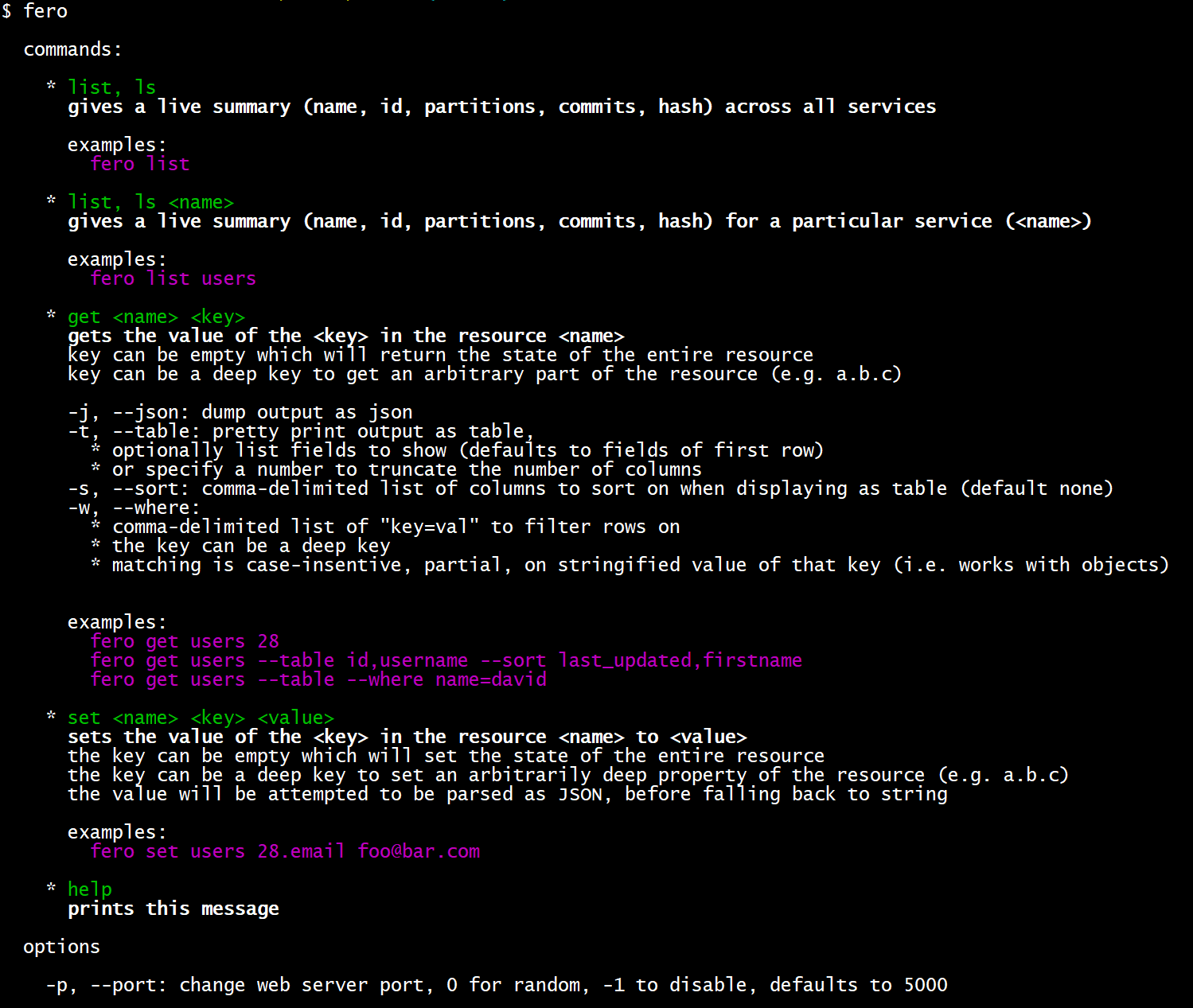

- Ripple, Testing, Credits, API, CLI & License

(fero ls, whilst running test that spins up 10 servers, 10 clients, fires 100 messages from each client, waits till replicated to all nodes, then tears down)

The request-response paradigm alone architecturally scales poorly across microservices. In contrast, the stream processing paradigm allows you to set up a declarative workflow of streams across the network, where each step in the reactive chain can be independently scaled. For a light intro, see Turning the Database Inside Out.

Whilst stateless services are easy to scale and operate, the cost of going to another service or database on every request is sometimes not acceptable. This also just pushes the bottleneck and problem of distribution further downstream, or poorly managed adhoc caches mushroom. The lack of state makes them severely limited, hence the motivation is to be able to create services that are as easy to dynamically scale as AWS Lamda, but with replicated shared state.

The core data structure is an immutable append-only changelog, which makes it easy to synchronise state across peers or bring up a new replica in case of crashes. Data is dynamically sharded into partitions (top-level keys by default). Writes for a partition can only happen on one node, but reads from anywhere. Each node will be the master for some partitions and once it commits an update, it propagates it to all the other peers/clients. Partition ownership is evenly distributed across how many ever instances you have, and new instances are minimally disruptive (i.e. only 1/N of the partitions are taken over by the new instance). The partitions are completely transparent to consumers. You can send an update to any node, and it will either handle it or proxy it to the right owner to handle, which makes it easy to use and latencies more predictable (at most 2 hops). All nodes can dynamically agree on which node should handle a particular request without co-ordination using the magic of consistent hashrings.

The following is the most basic example (simply run more instances to scale - they will automatically discover peers and connect to each other via UDP and/or TCP if a port range is specified).

sessions = await fero('sessions')The result (sessions) is a POJO - i.e. you have a distributed cache out of the box. There are some helper functions (update/remove/push/add/merge/etc) you can use to update the cache which is the same across all nodes:

sessions.update(key, value)This just creates and sends a change record to one of the peers. You can .send() arbitrary messages to a service yourself, and define a handler to manage your own set of actions (see below):

sessions.peers.send({ type: 'UPDATE', key, value })The change will be handled by the master node for that key, committed, and the commit is then replicated to all other nodes. Try committing in one terminal and observing the cache in another.

The cache also implements this observable interface, so you can map/filter/reduce and react to changes over time:

sessions

.on('change')

.map(...)

.filter(...)

.reduce(...)Or more fluently and interchangeably use callbacks or promises as appropiate:

await sessions.once('connected')In order for your service to handle other actions besides ADD/UPDATE/REMOVE, you can pass in a function as the second argument. Our users service looks something like:

users = await fero('users', async req =>

req.type == 'FORGOT' ? forgot(req)

: req.type == 'RESET' ? reset(req)

: req.type == 'LOGIN' ? login(req)

: req.type == 'LOGOUT' ? logout(req)

: req.type == 'REGISTER' ? register(req)

: req.type == 'EDIT' ? edit(req)

: req.type == 'APPROVE' ? approve(req)

: this.next(req) ? [200, 'ok']

: [405, 'method not allowed']That is, we have a distributed resource, that knows how to handle certain verbs (actions) on that resource, along with the default handler (next) to handle UPDATE/REMOVE/ADD requests and ignore anything else. The return value of the function will be the response to the request (or you can use req.reply(response)). Conventionally, all our responses here return a status code and message.

Note that you can also pass in an object to specify more options (see API). For example, to create a client node that just receives updates you can do:

sessions = await fero('sessions', { client: true })In our trial use case, we have some services that rely on other services and update their own state. For example a teams service which aggregates statistics from users, events and other services. Others are at the end of the reactive chain (i.e. sink) and map/filter changes that happen across various services and then cause side-effects, like journaling to disk, visualisation on a front-end or sending out emails. The notifications service declaratively defines in one place all the cases emails are sent, like the following:

users

.on('change')

.filter(d => d.type == 'ADD' && isFinite(d.key))

.map(({ value }) => email(drafts.users.join, value)(value))

.map(user => approversOf(user).map(email(drafts.users.approve, user)))-

Kafka relies on having a separate Zookeper cluster for electing a new master for a partition. Fero uses a DHT - a consistent hashring by default and this could later be made more sophisticated like Microsoft Orleans. Hence there is no reliance on any other system, which considerably simplifies operations and lowers the barrier to getting started.

-

There are no brokers - each node either handles a request or proxies it to the owner to handle.

-

Kafka makes your data between services distributed. You still need to write your own distributed services on top of that. Fero provides application-layer sharding, so you just write resources/services that are distributed in the first place. You simply process an incoming stream and produce an outgoing stream.

-

Kafka is one centralised cluster. So although you can conceptually think of your system as a dataflow graph, all the requests are going to one place. With Fero, this is also physically true. Since there's less overhead to spawning services, you can semantically split up your architecture into different services. Moreover each one of those services can be independently and dynamically scaled, completely transparent to other services that rely on it.

-

Partitions are fixed in Kafka and very visible to consumers. Fero aims for location-transparency, you never have to care about the underlying partitions. Partitions are also more dynamic in fero (top-level keys by default) rather than being fixed upfront.

-

Kafka stores the log to disk - albeit in a sequential way that makes it comparably as fast as storing in-memory. This gives you a consistent throughput when you are writing terabytes of data, because there is no max memory limit that you can overrun. You can process terabytes of data with fero, but it won't store it in memory. If you want to keep everything since time 0, you would typically have a fast critical path, and then pipe commits to a separate audit service to store, or for slower consumers, batch processing, historical analysis etc. Fero is also agnostic from where you load your initial state, whether it's a file, database, or something else (see

connectfunction) so you probably wouldn't use disk for this anyway. -

Although there are other in-sync replicas (ISR's) for a partition, only one master node is ever serving requests with Kafka. In contrast, although fero only does writes for a partition on one node, you can read from any replica, hence you can scale the two independently. The replica variables will be made more configurable in the future so you can adjust the dial as you please.

-

Kafka's is written in Java and that's where most of the magic is. If you try to use the Node client for example, you will get uncomparably worse performance. Fero is written in Node however and is as performant as the Java version.

-

Fero allows you to more fluently express the guarantees you want as required by your business logic. For example, the following would just fire off a message, no-blocking:

client.peers.send(...)

The following would wait for the asynchronous

ack(very fast):await client.peers.send(...).on('ack')

The following would wait for the request to be processed and the reply:

const result = await client.peers.send(...).on('reply')

Accordingly, the equivalent of the Kafka replication factor, would be for your service to just

awaittheackof a commit from how many other peers you like before proceeding.

The aim of these tests are not show they have the best 99.999th percentile latency, but that they are good for 99.999% of the use cases. The benchmark spins up a configurable number of clients and servers, fires a configurable number of messages from the clients with a configurable size in bytes, then reports back:

tacks(transmission acks) - the time taken, records/sec and speed (MB/s) to send the messagesyacks(asynchronous acks) - the time taken, records/sec and speed (MB/s) to acknowledge the messagessacks(synchronous acks) - the time taken, records/sec and speed (MB/s) for all the requests to be processed and replies received.

You can run the speed benchmarks (node tests/integration/speed/sync) with the following options:

-m: The size of messages. Can be comma-delimited. Default is 100 bytes.-r: The number of messages to send. Can be comma-delimited. Default is 1 million.-l: The number of clients to spin up. Can be comma-delimited. Default is 1.-c: The number of servers to spin up. Can be comma-delimited. Default is 1.

If you specify a list, each permutation will be run. For example, the following would run 6 tests:

-m 10,100,1000 -r 100000,1000000

The following are the results for sending a million messages of 10, 100, 1000 bytes long:

$ node tests/integration/speed/sync -m 10,100,1000

[log][2017-06-27T00:03:51.003Z][fero/benchmark/speed] records 1000000

[log][2017-06-27T00:03:51.003Z][fero/benchmark/speed] message 10, 100, 1000 bytes

[log][2017-06-27T00:03:51.003Z][fero/benchmark/speed] cluster 1 peers

[log][2017-06-27T00:03:51.003Z][fero/benchmark/speed] clients 1 clients

[log][2017-06-27T00:03:51.237Z][fero/benchmark/cluster] cluster peer stable 1739924977

[log][2017-06-27T00:03:51.237Z][fero/benchmark/cluster] cluster stable ( 1 )

[log][2017-06-27T00:03:51.706Z][fero/benchmark/clients] clients connected ( 1 )

[log][2017-06-27T00:04:00.409Z][fero/benchmark/speed]

1000000 records, 1 peers, 1 clients, 10 bytes

* stable: 0 ms

* connected: 0 ms

* tacks: 242.86 ms (0.24 sec) | 4117499.04 records/sec | 39.26 MB/sec

* yacks: 929.66 ms (0.92 sec) | 1075657.01 records/sec | 10.25 MB/sec

* sacks: 4814.66 ms (4.81 sec) | 207698.58 records/sec | 1.98 MB/sec

[log][2017-06-27T00:04:00.674Z][fero/benchmark/cluster] cluster peer stable 1739924977

[log][2017-06-27T00:04:00.674Z][fero/benchmark/cluster] cluster stable ( 1 )

[log][2017-06-27T00:04:01.143Z][fero/benchmark/clients] clients connected ( 1 )

[log][2017-06-27T00:04:11.674Z][fero/benchmark/speed]

1000000 records, 1 peers, 1 clients, 100 bytes

* stable: 0 ms

* connected: 0 ms

* tacks: 302.93 ms (0.3 sec) | 3301003.37 records/sec | 314.8 MB/sec

* yacks: 1323.76 ms (1.32 sec) | 755419.47 records/sec | 72.04 MB/sec

* sacks: 4975.7 ms (4.97 sec) | 200976.64 records/sec | 19.16 MB/sec

[log][2017-06-27T00:04:11.940Z][fero/benchmark/cluster] cluster peer stable 1739924977

[log][2017-06-27T00:04:11.940Z][fero/benchmark/cluster] cluster stable ( 1 )

[log][2017-06-27T00:04:12.503Z][fero/benchmark/clients] clients connected ( 1 )

[log][2017-06-27T00:04:38.909Z][fero/benchmark/speed]

1000000 records, 1 peers, 1 clients, 1000 bytes

* stable: 0 ms

* connected: 0 ms

* tacks: 1218.74 ms (1.21 sec) | 820517.53 records/sec | 782.5 MB/sec

* yacks: 5906.16 ms (5.9 sec) | 169314.56 records/sec | 161.47 MB/sec

* sacks: 6258.1 ms (6.25 sec) | 159792.85 records/sec | 152.39 MB/secFor comparison, these results are modelled similar to the Kafka benchmark. The asynchronous throughput is about ~75 MB/sec (795,064 records/sec) for the 100 byte case, which is similar to Fero at ~72 MB/sec (755,419 records/sec). Smaller message sizes really stress test the overheads of the system, whereas sending larger messages is basically testing TCP. As the message size increases, the records/sec decreases but the overall throughput goes up much higher as there is less overhead. Fero appears (based on the graph) to perform better at both 10 bytes (~10 MB/s vs ~5 MB/s), and 1000 bytes (~161 MB/s vs ~80 MB/s). Anything over 100 bytes and you are likely saturating a 1 gigabit NIC - i.e. fero is very unlikely to be your limiting factor.

In the same spirit of "lazy benchmarking", the latency tests with no configuration is:

$ node tests/integration/speed/latency/client

mean 0.07 ms

10 percentile 0.05 ms

50 percentile 0.06 ms

90 percentile 0.11 ms

99 percentile 0.3 ms

99.9 percentile 1.86 ms

99.99 percentile 3.72 ms

The latency test here is the similar to the ZeroMQ and Kafka ones - fire a single message and time how long it takes for the response to be received, repeat this many times. It does this 10,000 times by default, hence why it goes up to 99.99th percentile, but you can configure this with --messages if you want to go further. Note that the above is the time taken for the roundtrip (client to server and back) not one-way as ZeroMQ reports. For comparison, Kafka takes 2ms (vs 0.06ms) for the median, 3 ms (vs 0.3ms) for 99th percentile and 14 ms (vs 1.86 ms) for the 99.9th percentile. ZeroMQ has an average latency of 0.06 ms (vs 0.07 ms).

Compared with Redis, it is much faster. All the parameters are comparable or favourable to Redis: In both cases we are setting (SET vs UPDATE) random keys (1m), with pipelining enabled, 50 clients vs 1 client, small messages (3 bytes vs 10 bytes) on an Intel Xeon machine - the best case scenario is 552,028.75 records/sec - which is ~1.6 MB/s (compared with 1,075,657.01 records/sec = 10.25 MB/sec). I didn't find any official latency stats for Redis.

The tests were run on a laptop with the following specs (note that the Kafka tests are run across multiple machines):

System Model: XPS 15 9550

OS: Name Microsoft Windows 10 Pro

Processor: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-6700HQ CPU @ 2.60GHz, 2601 Mhz, 4 Core(s), 8 Logical Processor(s)

RAM: 32.0 GB

Node v8.0.0

The results are much higher if you run nodes on separate machines, on the cheapest DigitalOcean option. I haven't discussed those results, or cluster characteristics, because the tests should completely automate and make repeatable spinning up clusters on DO/AWS/etc. The TL;DR is that it scales horizontally similar to Kafka (so 3x would be 3 million messages per second on the cheapest DO servers), since each client also has a hashring and knows which partitions to write to directly.

How is Fero so fast? The main thing is to be performance concious at every step. Similar to Kafka, the throughput speed comes down to batching techniques (which you can configure in a similar way). Another technique that improved performance was "lazy deserialisation" of messages. When you look at protobuf generated code, it starts with while (!done), which means it tries to eagerly deserialise everything even if you only need to read one field. If you have a message with 70 fields, but only ever need to read 5 of them this is very wasteful. For change records, the header stores the offsets. The values are only sliced out (zero-copy) and memoized - when they are actually accessed. Likewise they are only serialised when you actually try to access the buffer representation. Another factor is shaping the API to be ergonomic and avoid any slow code in critical paths - for example although you can await the response of a single send, there is no Promise creation until you actually call .on('ack|reply'). Converting everything to use prototypes also boosted performance, as well as moving to Node v8.0.0. It would be interesting to see how the performance is further improved when TurboFan+Ignition land in V8.

Most of the optimisation has been around the async flow, there's still a lot more to do around the other paths.

-

Since this is very experimental, feedback on the design or API would be very welcome.

-

For more concrete contributions, the best thing is to try break a cluster with a test. In order to build confidence in a distributed system, a large set of real and challenging tests are required, hence some effort has been put into making it easy to write them. For example, with just a few lines of codes, there are tests that spin up 100 nodes at the same time to test connection/stabilisation, tests that fire a million records whilst a cluster is starting up, broken up and reconnected to test replication, etc.

-

Monitoring tools, being able to visualise the state of services, and interact with them is being worked on next - suggestions for what would be useful is welcome. There's also a Dapper-like tracing tool in the works (itself a fero service).

Fero services play particularly nicely with Ripple, giving you a fully reactive stack. Ripple acts as a reverse-proxy layer in front of your services. Your Ripple data resources are fero clients, instead of being embedded - which makes it easy to move from one to the other. You can use the standard Ripple transformation functions to proxy incoming requests, and declaratively define different representations on the client than on the server. After testing across a few more cases, we will genericise a small utility to do this for you easily.

Fero services are also made with testability in mind. You simply spin up your service(s) in the beforeEach, send it different requests objects, await the reply, assert as expected and tear down services(s) in the afterEach. The other aspect is observing state and side-effects in response to other services emitting a change.

// stores a count for the total number of changes to stream1 and stream2

export default counts({

stream1 = await fero('stream1', { client: true })

, stream2 = await fero('stream2', { client: true })

}) {

const counts = fero('counts', req => ...)

stream1

.on('change')

.reduce(acc => ++acc)

.map(d => counts.update('stream1', d))

stream2

.on('change')

.reduce(acc => ++acc)

.map(d => counts.update('stream2', d))

return counts

}You can specify the real value as defaults, then provide mocked versions of dependencies in your tests. For unit tests, you can just pass in a literal object to mock other services/cache, or if you depend on listening for updates, emitterify the object so it has the same interface and then emit change events. For integration tests, you can inject real fero clients and also create the corresponding real fero server nodes that you manipulate in each test. We currently have hundreds tests of integration tests that spawns real services and runs in under a minute. We're also changing our end-to-end tests to work in a similar fashion (spawn services, ripple and headless chrome).

For debugging, you can enable debug logs with the DEBUG=fero environment variable.

The following were super helpful:

- @rjrodger - for an early discussion on Uber's approach to SWIM and Tchannel, that led me to Ringpop

- @martinkl - "Turning the Database Inside Out"

- @caitie - "Building Scalable Stateful Services"

- @mranney - "Scaling Uber"

- @jaykreps - "The Log: What every software engineer should know about real-time data's unifying abstraction"

-

cache = awaitfero(name = '*', opts)-

name- The logical name of your service/resource/cache -

opts- This can be either your request handler function (from) or an object with the following:from- a function to handle incoming messagesconstants- an object to override any default constant valueshosts- an array of hosts to look for peers on (via TCP)ports [start, end]- an array, which is the range of ports server peers will start on, and be scanned for discovery. Server peers start on random ports if omitted.client- iftrue, this is a client node (i.e. does not own any partitions). In the future, this can also be a string which would be equivalent of Kafka consumer groups. Defaults tofalse.udp { ip = '224.0.0.251', port = 5354, ttl = 128 }- Multicast parameters used to discover other peers. Iffalse, skips discovery via UDP altogether.hash- the hash function used by the consistent hashring

Returns a promise that resolves to an instance of

Cache -

-

caches = awaitfero.all([names], opts)Convenience wrapper that spawns multiple instances, one for each of the items in the

namesarray with the specifiedopts. Resolves to an object that references each instance by it's name once they are all initialised. -

cache.set(change)- apply the specified change record. All possible mutations can be reified as either an update, remove or add change. If on a client, this will be sent to a server to process and then the commit will be later applied locally. If on the server, but not the owner, it will be forwarded to the correct peer to handle and commit to the log. -

cache.update(key, value)- create and apply an update change record, setting the value at the specified key. Note that the key can be arbitrarily deep. -

cache.remove(key)- create and apply a remove change record, removing the value at the specified key. Note that the key can be arbitrarily deep. -

cache.add(key, value)- create and apply an add change record, adding the value at the specified key. Note that the key can be arbitrarily deep. -

cache.push([key, ]value)- create and apply an add change record, adding the value at the end of the array specified by the key. Note that the key can be arbitrarily deep. -

cache.patch([key, ]values)- create and apply multiple change records for each key/value in values, at the specified key. Note that the key can be arbitrarily deep. -

cache.destroy()- tears down the instance and all active handles (timers, sockets, servers), allowing processes to naturally exit

For events, the Cache implements the emitterify interface, so you can use all the following events as callbacks, promises, or observables:

cache.on('commit', change => ...)- Fired when a new commit has been receivedcache.on('change', change => ...)- Fired when a change has been appliedcache.on('proxy', message => ...)- Fired when a new message has been received (server peers only). This is where the peer lookups up the partition the message belongs to, and then the owner for that partition, and then decides whether to handle (it is the owner) or forward it to the owner to handle.cache.on('ack', offset => ...)- Fired when a message has been acknowledgedcache.on('reply', reply => ...)- Fired when a reply to a message has been receivedcache.on('status', (status, peer) => ...)- Fired when a peer changes statuscache.on('disconnected', (status, peer) => ...)- Fired when a peer changes status todisconnectedcache.on('connecting', (status, peer) => ...)- Fired when a peer changes status toconnectingcache.on('connected', (status, peer) => ...)- Fired when a peer changes status toconnected(i.e. server connected)cache.on('removed', (status, peer) => ...)- Fired when a peer changes status toremovedcache.on('client', (status, peer) => ...)- Fired when a peer changes status toclient(i.e. client connected)

The Cache has two main subsystems: Peers and Partitions.

cache.peers is essentially just a pool of known peers. They can be automatically added by discovery via UDP, TCP, during synchronisation with another peer, or manually (see create). The main role of this module is to maintain a list of connected peers (up to constants.connections.max). When a peer gets disconnected, it tries to reconnect with the defined retry strategy. If the number of peers drops below the specified threshold, it starts to connect more disconnected peers in the pool. This also implements the iterator Symbol, so you can use for of to iterate through all peers.

peers.name- the logical name of this service/cachepeers.me{ host, port, address, id, raw }- the details of the local server. This isfalsefor client nodes as they do not start a TCP server.peers.lists{ disconnected, connected, connecting, throttled, client, all }- index peers by status as arrays to make it more efficient to iterate through only a certain type of peers.peers.create(host, port)- programmatically create and add a new peer.peers.remove()- programmatically drop a peer.peers.send(message)- sendmessageto one of the server nodes.peers.owner(change)- this is a shorthand to look up which partition a change belongs to, then which peer owns that partition, and memoises the result.

peer.host- the remote host of the peerpeer.port- the remote port of the peerpeer.address- shorthand forhost:portpeer.id- the id of the peerpeer.uuid- randomly assigned number used for debuggingpeer.socket- the raw TCP socket to the peerpeer.status- the connection status of the peer (disconnected | connected | connecting | throttled | client)peer.send(message)- send this particular peer a message

The Partitions is essentially a map of Partition's. Partition is just a log of change records. This module just listens for commits and appends them to the corresponding log, update the state of the cache. You can specify your own partitioning strategy as a function, but essentially it should result in orthogonal partitions. The default is by top-level keys, but you can imagine other strategies, like by user/IP/ID/session/etc, which would result in magically co-locating peers that deal with a particular users data across different services onto a single machine.

connect is a utility that just makes it easier to connecting a node to something.

const { fero, connect } = require('fero')

, db = { restore, add, update, remove }

, server = await connect(db)(fero('users', processor))This will do two things:

-

restore - it will wait a configurable amount of time before either joining an existing cluster, or considering itself the first peer of the cluster and invoking the

restorefunction ondbto restore initial state -

replay - if the functions

add/update/removeare defined ondb, they will be invoked for the when the corresponding change occurs

Constants can be set via the command-line (e.g. --constants.outbox.max), overriden in JS (e.g. { constants: { outbox: { max: 0 }}}) on construction, otherwise it will use the default value.

| Key | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|

dht.vnodes |

200 |

The number of additional virtual nodes created for each peer on the hashring to even out hotspots and create an even distribution |

connect.wait |

1000 |

How many milliseconds to wait to discover other peers before considering this server as the first peer in the cluster and invoking the restore function to restore initial state |

retries.base |

100 |

The milliseconds to wait using exponential backoff on the first attempt to retry connecting to a peer |

retries.cap |

60000 |

The maximum ceiling in milliseconds a retry attempt will be scheduled |

retries.max |

5 |

The maximum number of retry attempts before declaring a peer a failure and dropping it |

retries.jitter |

0.5 |

The percentage of randomness to multiply a retry timeout by to avoid self-similar behaviour. See AWS Architecture Blog: Exponential Backoff And Jitter for more info. |

connections.timeout |

10000 |

The maximum milliseconds connection to a peer can take before timing out |

connections.jitter |

200 |

The maximum amount of delay to add before attempting to connect to another peer. This is required otherwise peers will all try to connect at the same time, both will think the other is already connecting, then disconnect, then keep repeating. See Thundering Herd Problem. |

connections.max.server |

Infinity |

The maximum number of connections to other peers for a server node |

connections.max.client |

1 |

The maximum number of connections to other peers for a client node |

udp.skip |

false |

Skip trying to discover other peers via UDP |

udp.jitter |

2000 |

The maximum amount of delay to add before attempting to discover another peer via UDP. |

udp.retry |

false |

Determines whether it will periodically keep searching for other server peers until at least one is found. This is always true for clients since it doesn't make sense to client not connected to any server peers |

partitions.history.max |

Infinity |

The maximum number of log |

outbox.max |

2**28 |

The maximum outbox buffer size in bytes, after which a flush will be forced if surpassed within one microtask. Setting to 0 will effectively disable any batching. |

outbox.frag |

2**16 |

The maximum message size that can be buffered across partial TCP data events |

MIT License © Pedram Emrouznejad