Waterloo Place

Waterloo Place in 2015, looking south | |

| Length | 248 m (814 ft)[1] |

|---|---|

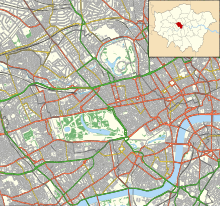

| Location | Westminster, London, United Kingdom |

| Postal code | SW1 |

| Nearest train station | |

| Coordinates | 51°30′24″N 0°07′56″W / 51.506764°N 0.132159°W |

| North end | Lower Regent Street |

| South end | Duke of York Steps and The Mall |

| Construction | |

| Inauguration | 1815 |

| Other | |

| Known for |

|

Waterloo Place is a short but broad street in the St James's area of the City of Westminster, London. It forms a plaza-like space and is a southern extension of Lower Regent Street. Towards the northern end it is crossed by Pall Mall and at the southern end, by Carlton House Terrace, where it ends at the Duke of York Steps which lead down to The Mall. Located on the Place are several 19th and 20th century monuments to royalty, explorers and military people.

History

[edit]

Included in the plan for London prepared by architect John Nash in 1814 was a broad plaza intended as a space for monuments,[2] It would be the southern end of a prestigious new thoroughfare, later known as Regent Street,[3] and would create a grand open area in front of Carlton House, the London residence of the Prince Regent, which stood on the south side of Pall Mall. The site had previously been occupied by St James's Market,[4] and several "low and mean houses" had to be demolished to make way for the development.[5] Construction was financed and managed by the property developer, James Burton. The first leases on the new buildings in the street were taken out in 1815,[4] by which time it was thought appropriate to name it after the British victory at the Battle of Waterloo which had taken place in June of that year, perhaps as a military counterpart to Trafalgar Square.[6]

Residences in Waterloo Place quickly became fashionable due to the proximity to Carlton House. Charlotte Lennox, Duchess of Richmond lived at Number 7, while Lady Elizabeth Egremont, the estranged wife and former mistress of George Wyndham, 3rd Earl of Egremont, lived at Number 4.[4] Following a fire in 1824, Carlton House was demolished and part of the vacant plot on the western corner of Pall Mall and Waterloo Place was offered by Parliament to the Athenaeum Club who were in temporary premises nearby. Accordingly, in 1826, Decimus Burton, the son of the developer, was commissioned to design an elegant building for the club. Parliament also offered the opposite site to the United Service Club with the specification that both buildings should be of a uniform design. However, the latter club were able to get agreement to some modifications that the Athenaeum were unwilling to follow, so that the two finished buildings were dissimilar.[7]

Monuments

[edit]The focal point of Waterloo Place is the 120 feet (37 m) Duke of York Column, commemorating Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, the commander-in-chief of the British Army during the Napoleonic Wars. It stands above a flight of steps leading down to The Mall in a space between the Western and Eastern terraces of the Carleton House Terrace, designed by Nash and Decimus Burton and built between 1827 and 1832. The column itself was designed by Benjamin Dean Wyatt and was completed in 1832.

Waterloo Place later became a space for memorialising non-royal heroism, due to it being Crown land and therefore administered by the Commissioners of Woods, Forests and Land Revenues, who were more amenable to public monuments than the Commissioners of Works and Public Buildings that controlled many other open spaces in the capital. The first of these was the Guards Crimean War Memorial, sculpted by John Bell and completed in 1861, which occupies a central position in the place. On the western edge, Matthew Noble's statue of Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin was unveiled in 1866, followed the next year by Carlo Marochetti's memorial to Crimean War hero, Colin Campbell, 1st Baron Clyde on the eastern side. In 1874, another Crimean general, John Fox Burgoyne was commemorated in a statue by Joseph Edgar Boehm, who also executed another to a Viceroy of India, John Lawrence, 1st Baron Lawrence completed in 1885.

In 1914, John Henry Foley's 1866 statue of Sidney Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Lea, the Secretary at War during the Crimean War, was moved from outside the War Office in Whitehall to stand close to the Guards memorial in Waterloo Place. It was joined in the following year by a new statue of Florence Nightingale by Arthur George Walker, making a group of three Crimean memorials in the centre of the roadway. Also in 1915, a statue of the Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott, sculpted by his widow, Kathleen, was erected next to that of Lord Clyde. In 1924, an equestrian statue of King Edward VII by Sir Edgar Bertram Mackennal was unveiled, also in the centre of the Place.[8] The last addition was a memorial by Leslie Johnson to Sir Keith Park, known as "the defender of London" during the Battle of Britain, which was installed in 2010 next to Scott and Franklin.[9]

-

Duke of York Column

-

The Guards Crimean War Memorial together with statues of Florence Nightingale (left) and Lord Lea

-

Statue of Sir John Franklin

-

Statue of Lord Clyde

-

Statue of Field Marshal Burgoyne

-

Statue of Lord Lawrence

-

Statue of Captain Scott

-

Statue of King Edward VII

-

Statue of Air Chief Marshal Park

References

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Barczewski, Stephanie L. (2016). Heroic Failure and the British. New Haven CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300180060.

- Hitchcock, Henry-Russell (1958). Architecture: Nineteenth And Twentieth Centuries. Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books.

- Johnson, Trench H. (1906). Phrases and Names, their Origins and Meanings. London: T. Warner Laurie.

- Kershman, Andrew (2007). London's Monuments. London: Metro Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-1902910253.

- Summerson, John Newenam (1935). John Nash: Architect to King George IV. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Walford, Edward (1878). "Waterloo Place and Her Majesty's Theatre". Old and New London: Volume 4. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin.

- Stevens, Quentin; Franck, Karen A. (2016). Memorials as Spaces of Engagement: Design, Use and Meaning. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415631440.

- Ward, Thomas Humphrey (1926). History of the Athenæum, 1824-1925. London: Athenæum Club.