The Sanctuary

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Wiltshire, United Kingdom |

| Part of | Avebury Section of Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii), (iii) |

| Reference | 373bis-002 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

| Extensions | 2008 |

| Coordinates | 51°24′36″N 1°49′54″W / 51.41000°N 1.83170°W |

The Sanctuary was a stone and timber circle near the village of Avebury in the south-western English county of Wiltshire. Excavation has revealed the location of the 58 stone sockets and 62 post-holes. The ring was part of a tradition of stone circle construction that spread throughout much of Britain, Ireland, and Brittany during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, over a period between 3300 and 900 BCE. The purpose of such monuments is unknown, although archaeologists speculate that the stones represented supernatural entities for the circle's builders.

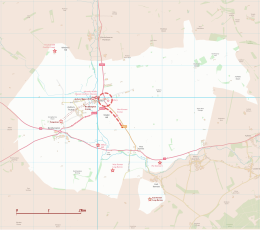

The Sanctuary was erected on Overton Hill, overlooking older Early Neolithic sites like West Kennet Long Barrow and East Kennet Long Barrow. It was connected to the Late Neolithic henge and stone circle at Avebury via the West Kennet Avenue of stones. It also lies close to the route of the prehistoric Ridgeway and near several Bronze Age barrows.

In the early 18th century, the site was recorded by the antiquarian William Stukeley although the stones were destroyed by local farmers in the 1720s. The Sanctuary underwent archaeological excavation by Maud and Ben Cunnington in 1930, after which the location of the prehistoric posts was marked out by concrete posts. Now a scheduled monument[1] under the guardianship of English Heritage,[2] it is classified as part of the "Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites" UNESCO World Heritage Site[3] and is open without charge to visitors all year round.[2]

Location

[edit]The Sanctuary is 1 ½ miles southeast of Avebury and 4 ½ miles west of Marlborough.[4] It stands on the southern spur of Overton Hill,[5] a site offering views across the valley of the River Kennet.[5]

Visitors can park on a lay-by on the southern side of the A4 atop Overton Hill, which is adjacent to the circle.[4] In its present state, the posts of the Sanctuary are marked by concrete markers.[5] The archaeologist Aubrey Burl noted that the site is "visually unexciting",[4] offering only a "dull and stunted concrete reproduction" that does "little for the uninstructed imagination".[6] The archaeologists Joshua Pollard and Andrew Reynolds noted that although it was "far from the most spectacular or evocative of the Avebury monuments", the site's significance "should not be understated".[5]

Context

[edit]While the transition from the Early Neolithic to the Late Neolithic in the fourth and third millennia BCE saw much economic and technological continuity, there was a considerable change in the style of monuments erected, particularly in what is now southern and eastern England.[7] By 3000 BCE, the long barrows, causewayed enclosures, and cursuses which had predominated in the Early Neolithic were no longer built, and had been replaced by circular monuments of various kinds.[7] These include earthen henges, timber circles, and stone circles.[8] Stone circles are found in most areas of Britain where stone is available, with the exception of the island's south-eastern corner.[9] They are most densely concentrated in south-western Britain and on the north-eastern horn of Scotland, near Aberdeen.[9] The tradition of their construction may have lasted for 2,400 years, from 3300 to 900 BCE, with the major phase of building taking place between 3000 and 1,300 BCE.[10]

These stone circles typically show very little evidence of human visitation during the period immediately following their creation.[11] This suggests that they were not sites used for rituals that left archaeologically visible evidence, but may have been deliberately left as "silent and empty monuments".[12] The archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson suggests that in Neolithic Britain, stone was associated with the dead, and wood with the living.[13] Other archaeologists have suggested that the stone might not represent ancestors, but rather other supernatural entities, such as deities.[12]

In the area of modern Wiltshire, various stone circles were erected, the best known of which are Avebury and Stonehenge. All of the other examples are ruined, and in some cases have been destroyed.[14] As noted by the archaeologist Aubrey Burl, these examples have left behind "only frustrating descriptions and vague positions".[14] Most of the known Wiltshire examples were erected on low-lying positions in the landscape.[14] There are four smaller stone circles known from the area surrounding Avebury: The Sanctuary, Winterbourne Bassett Stone Circle, Clatford Stone Circle, and Falkner's Circle.[15] Archaeologists initially suggested that a fifth example could be seen at Langdean Bottom, although further investigation has reinterpreted this as evidence for a late prehistoric hut circle or a medieval feature.[16] Burl suggested that these smaller stone related to Avebury in a manner akin to "village churches within the diocese of a cathedral".[17]

Design and construction

[edit]

The location on which the Sanctuary was built saw prior human activity. This is reflected by a scatter of Peterborough Ware discovered by archaeologists that possibly extends for several hundred metres to the north of the monument.[5] From its location on Overton Hill, the Sanctuary offers views of various Early Neolithic monuments in the landscape, including the West Kennet Long Barrow, East Kennet Long Barrow, and Windmill Hill.[5]

Excavation revealed that the Sanctuary consisted of two concentric rings with an overall diameter of circa 40 metres.[5] The inner stone circle was encompassed by six concentric rings of post holes, marking where timber posts had once stood.[5]

The first stage of activity at the site, some time around 3000 BCE, consisted of a ring of eight wooden posts 4.5 metres (15 ft) across, with a central post, presumed to be a round hut.[18] Within 200 years the first ring was enlarged to 6m and a second ring was added, also of eight posts, but this time 11.2 metres (37 ft), perhaps creating a large hut or an enclosure.[19] Phase three, some time in the later Neolithic, a third ring of 33 posts were added, in a circle 21 metres (69 ft) across, and at the same time an inner stone circle of 15 or 16 sarsen stones was introduced alongside what was by that point the middle ring, making an almost solid wall of stones and posts.

The final phase was of 42 sarsen stones forming a boundary ring 40 metres (130 ft) across, which replaced all the timber structures.[19] This may have been built at a similar time to the Avebury stone circle, and had an entrance way that led into the Kennet Avenue, two parallel lines of stones running the 2.5 kilometres (1.6 miles) from The Sanctuary to Avebury.[18]

Links to the West Kennet Avenue

[edit]

The Sanctuary connects to the West Kennet Avenue, a line of stones stretching for 2.4 kilometres to the Avebury henge.[20] The point where the West Kennet Avenue connects with the Sanctuary may have been seen as the start of the Avenue or as its finish.[5]

Form and purpose

[edit]When the site was first excavated by Maud and Ben Cunnington in 1930,[21] it was interpreted as a timber equivalent to Stonehenge. 162 postholes were excavated, some with double posts and the remains of postpipes still visible. Later interpretations have made much of The Sanctuary's link with Avebury via the Avenue, and suggested that the two sites may have served different but complementary purposes. The timbers may have supported a roof of turf or thatch, to form a high-status dwelling serving the ritual site at Avebury, although this can only be conjectural. Another interpretation is that it served as a mortuary house where corpses were kept either before or after ritual treatment at Avebury. Neolithic pottery and animal bone were recovered by the Cunningtons, indicating that the site saw some degree of occupation activity. Recent excavation by Mike Pitts has given greater credence to the Cunningtons' original interpretation of freestanding posts.[19]

The site was largely destroyed in around 1723, although not before William Stukeley was able to visit and draw it.[22][23] The 1930 excavation revealed the body of a young girl buried alongside the eastern stone of the inner stone circle. She had been interred with a beaker and animal bones. Her body would have been aligned with the equinoctial sunrises, and Burl suggested that she may have been a sacrifice.[24]

It remains uncertain what purpose(s) the structures were put to. As a site that was in use for many hundreds of years it is likely that the purpose, like the form of the structures, changed considerably over the years.[18]

Antiquarian investigation

[edit]

The Sanctuary was observed by the antiquarian William Stukeley.[25] He drew it on 8 July 1723, calling it the "Temple of Ertha".[26] This was Stukeley's own variant of "Hertha", a name that was current among 17th and 18th-century antiquarians, and which was based on a reading of Tacitus's Germania, a first-century book which claimed that the Suebi of northern Europe worshipped a goddess named Nerthus.[26] When Stukeley returned and did more fieldwork at the Sanctuary on 18 May 1724, he referred to it instead as the "Temple on Overton Hill".[26] Stukeley noted that local people called it "The Sanctuary".[26] The archaeologist Stuart Piggott later noted that this was "a rather improbable name for rural folklore, and suggesting some seventeenth-century antiquarianism at work".[27]

Stukeley's drawings of the Sanctuary depicted them as ovals, whereas later excavations revealed them to be almost perfect circles.[28] He later presented the idea that the circles represented the head of a large serpent marked out in megaliths across the landscape.[29] Stukeley also recorded the destruction of the Sanctuary by local farmers.[5]

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Historic England. "The Sanctuary, Overton Hill (1014563)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b "The Sanctuary, Avebury". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites (1000097)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Burl 2005, p. 86.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pollard & Reynolds 2002, p. 106.

- ^ Burl 2000, p. 311.

- ^ a b Hutton 2013, p. 81.

- ^ Hutton 2013, pp. 91–94.

- ^ a b Hutton 2013, p. 94.

- ^ Burl 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Hutton 2013, p. 97.

- ^ a b Hutton 2013, p. 98.

- ^ Hutton 2013, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b c Burl 2000, p. 310.

- ^ Gillings et al. 2008, p. 142.

- ^ Burl 2000, p. 310; Gillings et al. 2008, p. 142.

- ^ Burl 1979, p. 236.

- ^ a b c "History of the Sanctuary, Avebury". english-heritage.org.uk. 2006. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ a b c "The Sanctuary: HER id 4743". Wiltshire and Swindon Historic Environment Record. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Pollard & Reynolds 2002, p. 100.

- ^ M. E. Cunnington (1930). "The "Sanctuary" on Overton Hill, near Avebury". Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine. 45: 300–335 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Sanctuary". avebury-web.co.uk. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ "The "Silbaby" Question". avebury-web.co.uk. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Burl 2005, p. 87.

- ^ "Avebury: The Sanctuary". The Heritage Journal. 28 February 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Piggott 1985, p. 95.

- ^ Piggott 1985, p. 49.

- ^ Piggott 1985, p. 107.

- ^ Piggott 1985, p. 105.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burl, Aubrey (1979). Prehistoric Avebury. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 124–128, 193–198. ISBN 9780300023688 – via Internet Archive.

- Burl, Aubrey (2000). The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08347-7.

- Burl, Aubrey (2005). A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11406-5.

- Gillings, Mark; Pollard, Joshua; Wheatley, David; Peterson, Rick (2008). Landscape of the Megaliths: Excavation and Fieldwork on the Avebury Monuments, 1997–2003. Oxford: Oxbow. ISBN 978-1-84217-313-8.

- Hutton, Ronald (2013). Pagan Britain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19771-6.

- Piggott, Stuart (1985). William Stukeley: An Eighteenth-Century Antiquary (second ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500013601.

- Pollard, Joshua; Reynolds, Andrew (2002). Avebury: The Biography of a Landscape. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0752419572.

External links

[edit]- grid reference SU118679

- Places To Visit: The Sanctuary – English Heritage

- Pitts, Mike (February 2000). "Return to the Sanctuary". Archaeology. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011 – via Internet Archive.

- Avebury Sanctuary Stroll – National Trust 1-mile walk