Secession in Turkey

Secession in Turkey is a phenomenon caused by the desire of a number of minorities living in Turkey to secede and form independent national states.[1][2]

Kurdish separatism

[edit]At the beginning of the 21st century, the Kurds remain the largest of the groups without their own statehood. The Treaty of Sèvres between Ottoman Empire and Triple Entente (1920) provided for the creation of an independent Kurdistan. However, this agreement never entered into force and was cancelled after the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). In the 1920s and 1930s, Kurds several times unsuccessfully rebelled against the Turkish authorities.

In August 1984, the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) declared war on the Turkish authorities, which continues today. Until 1993, the PKK made the most radical demand – the proclamation of a single and independent Kurdistan, uniting the Kurdish territories that are now part of the state borders of Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria.

Since 1999, the PKK has put forward requirements that are close and understandable to the bulk of the Kurdish population, namely: granting autonomy, preserving national identity, practical equalization of Kurds in rights with the Turks, opening of national schools and introduction of Kurdish TV and radio broadcasting.

Armenian separatism

[edit]

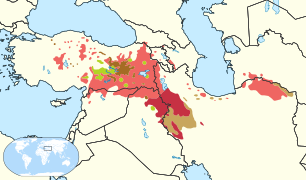

Orange: areas overwhelmingly populated by Armenians (Republic of Armenia: 98%;[9] Nagorno-Karabakh: 99%; Javakheti: 95%)

Yellow: Historically Armenian areas with presently no or insignificant Armenian population (Western Armenia and Nakhichevan)

Western Armenia (Western Armenian: Արեւմտեան Հայաստան, Arevmdian Hayasdan), located in Western Asia, is a term used to refer to eastern parts of Turkey (formerly the Ottoman Empire) that were part of the historical homeland of the Armenians.[10] Western Armenia, also referred to as Byzantine Armenia, emerged following the division of Greater Armenia between the Byzantine Empire (Western Armenia) and Sassanid Persia (Eastern Armenia) in 387 AD.

The area was conquered by the Ottomans in the 16th century during the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555) against their Iranian Safavid arch-rivals. Being passed on from the former to the latter, Ottoman rule over the region became only decisive after the Ottoman–Safavid War of 1623–1639.[11] The area then became known as Turkish Armenia or Ottoman Armenia. During the 19th century, the Russian Empire conquered all of Eastern Armenia from Iran,[12] and also some parts of Turkish Armenia, such as Kars. The region's Armenian population was affected during the Hamidian massacres.

The Armenian population was largely emptied from this region during the Armenian Genocide, such that only assimilated and crypto-Armenians live in the area today. Some irredentist Armenians claim it as part of United Armenia. The most notable political party with these views is the Armenian Revolutionary Federation.

See also

[edit]- Turkish War of Independence

- Minorities in Turkey

- Demographics of Turkey

- Languages of Turkey

- Geographical name changes in Turkey

- Human rights in Turkey

- Treaty of Sèvres

- Treaty of Lausanne

- Turkish Kurdistan

- Marwanids

- Western Armenia

- Lazistan

- Republic of Pontus

- Provisional Government of Western Thrace

- Dersim rebellion

- Sheikh Said rebellion

- Hatay Province

- Adjarians

- Chveneburi

- Chepni people

- Hemshin peoples

- Arsacid dynasty of Armenia

- Kurdish nationalism

- Language secessionism

References

[edit]- ^ "Renewed Turkish nationalism silences ethnic minorities". Ahval. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Kurds, Turks and the Alevi Revival in Turkey". MERIP. 22 September 1996. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Müftüler-Bac, Meltem (1999). "Addressing Kurdish Separatism in Turkey". In Ross, Marc Howard; Rothman, Jay (eds.). Theory and Practice in Ethnic Conflict Management: Theorizing Success and Failure. Ethnic and Intercommunity Conflict Series. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 103–119. doi:10.1057/9780230513082. hdl:11693/51474. ISBN 978-0-230-51308-2. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Tezcür, Güneş Murat (29 December 2009). "Kurdish Nationalism and Identity in Turkey: A Conceptual Reinterpretation". European Journal of Turkish Studies. Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey (10). doi:10.4000/ejts.4008. ISSN 1773-0546.

- ^ Hoffman, Max. "The State of the Turkish-Kurdish Conflict". Center for American Progress. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Chronology for Kurds in Turkey". Refworld. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "The Kurds in Turkey". fas.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2000.

- ^ "Kurds, Turks and the Alevi Revival in Turkey". MERIP. 22 September 1996. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "2011 Census Results" (PDF). armstat.am. National Statistical Service of Republic of Armenia. p. 144.

- ^ Myhill, John (2006). Language, Religion and National Identity in Europe and the Middle East: A historical study. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-272-9351-0.

- ^ Wallimann, Isidor; Dobkowski, Michael N. (March 2000). Genocide and the Modern Age: Etiology and Case Studies of Mass Death. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815628286. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Dowling, Timothy C. (2 December 2014). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-948-6.