Ludovic Dauș

Ludovic Dauș | |

|---|---|

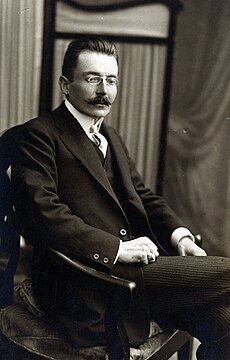

Photographic portrait of Dauș | |

| Born | October 1, 1873 Botoșani, Principality of Romania |

| Died | November 17, 1954 (aged 81) Bucharest, Romanian People's Republic |

| Pen name | Adina G., Adrian Daria, Ludovic D. |

| Occupation | novelist, playwright, poet, translator, theatrical manager, clerk, politician |

| Nationality | Romanian (from 1899) |

| Alma mater | University of Bucharest |

| Period | c. 1890–1954 |

| Genre | Social novel, political fiction, novella, psychological novel, verse drama, historical play, melodrama, erotic literature, epic poetry, lyric poetry |

| Literary movement | Neo-romanticism, Literatorul, Sburătorul |

Ludovic Dauș (October 1 [O.S. September 19] 1873 – November 17, 1954)[1] was a Romanian novelist, playwright, poet and translator, also known for his contributions as a politician and theatrical manager. He was born into a cosmopolitan family, with a Czech father and a boyaress mother, but his formative years were marked by life in the small boroughs of Western Moldavia. Trained as a lawyer and employed for a while as a publisher, Dauș joined the body of experts at the Ministry of Royal Domains, climbing through the bureaucratic ranks. In parallel, he advanced his literary career: a noted dramatist, he was an unremarked poet and historical novelist prior to World War I. His translation work covered several languages, and includes Romanian versions of The Kreutzer Sonata, Madame Bovary, and Eugénie Grandet.

As a youth, Dauș was primarily interested in reviving neo-romanticism, which became the core stylistic influence in his novels and plays. After being welcomed into the literary salon headed by Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, he moved between literary clubs. By 1918, he had adopted a Romanian nationalist discourse in his poetry and, increasingly, in his political career. He had several new commissions in Greater Romania, and in particular Bessarabia, where he is remembered as the first chairman of Chișinău National Theater. Dauș went on to serve in the Assembly of Deputies and Senate, where he affirmed the interests of Bessarabian peasants and advocated radical land reform; initially a member of the local Independent Party, he later caucused with the National Liberals.

During the interwar, Dauș was loosely affiliated with the modernist circle Sburătorul. He matured as a writer, earning praise and drawing controversy with works of political fiction which bridged a neo-romantic, quasi-traditionalist, subject matter with elements of the psychological novel; he also shocked theatergoers with his explicit play about Vlad Țepeș. He continued to work for the stage during World War II. Also then, he became a confidant of, and apologist for, his fellow novelist Liviu Rebreanu, becoming a personal witness to Rebreanu's final days, which they spent together at Valea Mare. In his seventies, Dauș was manager of Caragiale Theater, but retired shortly before the inauguration of a communist regime. He died in Bucharest at the age of 81.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Ludovic Dauș's exact birthplace was his family's home on Sfinții Voievozi Street of Botoșani.[2] He was the son of Alfred Dauș (also Dausch, Dousa, Dușa, or Bouschek).[3] An engineer of Czech ethnicity,[2][4][5] he had been born at Dolní Lochov, Bohemia in 1845, and baptized a Catholic.[6] Dauș Sr had settled in the United Principalities and taken up various activities in his field of expertise. According to various records, he had participated in the January Uprising, supporting the Polish National Government;[2][7] other sources note that he had lived for a while in Ottoman Bosnia.[8] In 1880, he helped establish an iron foundry for Botoșani's apprentice smiths.[6] By 1897, he was Botoșani County's official surveyor, and, as a protégé of its Prefect, Ion Arapu, stood accused of having mistreated government employees working under his watch.[9] Ludovic's mother was Maria Negri, a niece of the Moldavian writer Costache Negri, reportedly educated in Lviv.[8] Through her, Dauș was a member of the boyar aristocracy.[10]

The future writer was baptized into the Romanian Orthodox Church, to which his mother belonged.[6] Though his father had been fully naturalized in February 1886,[6] Ludovic only took Romanian citizenship in 1899.[11] He finished primary school in his native town, afterwards enlisting at the local A. T. Laurian National College, where he studied in 1884–1887.[2] He prepared for a career in the Romanian Land Forces, enlisting at the Military School of Iași, but disliked the conditions there and moved to Fălticeni.[10] There, he studied for a while under Eugen Lovinescu, before returning to his home city, and finally to Bucharest, where he attended Sfântu Gheorghe High School—a private school managed by Anghel Demetriescu and George Ionescu-Gion. During the period, he had his very first poems appear in Ioniță Scipione Bădescu's Botoșani paper, Curierul Român.[12] According to his own recollections, he was heavily inspired by the elegiac poetry of Vasile Alecsandri and Heinrich Heine. From such beginnings, he switched to writing "naive, stupid" works, including a dramatic poem "where the protagonist was the head of a decapitated man."[13] Botoșani and Fălticeni, as prototypes of the Western Moldavian târg, would later form the backdrop for his prose, which includes specific allusions to his school years.[14]

After taking his baccalaureate in June 1892, Dauș entered the civil service as a copyist at the Ministry of Royal Domains.[15] In October 1895, the National Theater Bucharest took up his translation of François Coppée's Les Jacobites. Ioan Bacalbașa gave the play a poor review, noting that Dauș had spent his efforts on prosody rather than ensuring that the play was watchable.[16] He subsequently earned a law degree from the University of Bucharest (1897)[4][17] and practiced as a lawyer. While still pursuing his career in the national bureaucracy, Dauș entered the publishing business as co-manager of Alcaly publishers, coordinating their serial Biblioteca pentru toți; the nominal owner, Leon Alcaly, was illiterate.[18] According to researcher Ștefan Cevratiuc, his first published volume was a novella collection, appearing in 1897 as Spre moarte ("Unto Death").[2]

Neo-romantic affiliations

[edit]Dauș married Margot Soutzo, of the Soutzos clan, then divorced and, in 1910, remarried to the Frenchwoman Ecaterina Thiéry.[19] He continued to publish poetry, some of it in Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu's Revista Nouă—an "obscure", "entirely impersonal" endeavor, according to historian George Călinescu.[20] He debuted as a translator in 1896, with Antoine François Prévost's Manon Lescaut, later publishing renditions of Molière (The Imaginary Invalid, 1906), Ivan Turgenev (The Duelist, 1907), Jonathan Swift (Gulliver's Travels, 1908), E. T. A. Hoffmann (Stories, 1909), Leo Tolstoy (The Kreutzer Sonata, 1909), and Arthur Conan Doyle (1909).[4][21] During those years, as a protege of Ionescu-Gion's, he frequented Hasdeu's literary salon at Editura Socec, where he met and befriended the fellow poet and dramatist Haralamb Lecca.[22] He was also noted as a court poet of the Romanian Queen-consort, Elisabeth, writing her a poem for her anniversary in December 1901.[23]

Dauș followed up with more dramatic poems of his own, usually performed at the National Theater. The series began with plays inspired by Lithuanian history: Akmiutis, in 1898;[4] and, in 1903, the five-act Eglà.[24] This work earned him a prize from the Romanian Academy,[25] but he was by then ridiculed in independent circles. Poet Ștefan Petică, who was also an animator of the Romanian Symbolist movement, described Akmiutis as an "unbearably lamentable melodrama",[26] while philologist Nerva Hodoș urged Dauș to quit writing altogether, after seeing Eglà.[27] Eglà was also covered by the National Liberal Party's newspaper, Voința Națională, which was criticizing the selection of plays made by the National Theater: "In a two-month program, they only hand us a single original [Romanian] creation, and it is one of the weakest".[28]

In 1902, Dauș returned with Patru săbii ("Four Swords"); followed in 1904 by Blestemul ("The Curse"); in 1906 by Doamna Oltea ("Lady Oltea"), dramatizing the lives of Prince Bogdan and Stephen the Great; and in 1912 by Cumpăna ("The Watershed"). Such works were alternated by novels and novellas: Străbunii ("The Forefathers", 1900); Dușmani ai Neamului ("Enemies of the Nation", 1904); and Iluzii ("Illusions", 1908).[4][29] Most such contributions focused on the legendary period before and during the Founding of Moldavia.[30] They were all panned by critic Ovid Crohmălniceanu, who sees Dauș's early career as "quite fecund, but producing only countless illegible works."[31] Dauș remained adamantly committed to the neo-romantic school, shunning literary realism. This became explicit in early 1899, when L'Indépendance Roumanie hosted his overview of Romanian theatrical life: as noted by the literary scholar Dan C. Mihăilescu, Dauș had tied its evolution to Hasdeu and Lecca, without even mentioning the realist doyen, Ion Luca Caragiale.[32]

Dauș soon became loosely affiliated with Literatorul magazine, which reunited Romanian Symbolists with poets who had left the Hasdeu circle. According to historian Nicolae Iorga, at that stage Dauș was still a "literary dilettante".[33] His various works were by then carried by publications of many hues, including Familia, Luceafărul, Vatra, and Literatură și Știință.[34] In Adevărul daily, he published several popular translations in feuilleton, using the pen name "Adrian Daria";[35] other pseudonyms he used for such work include "Adina G." and "Ludovic D." (the latter used for George Ranetti's Zeflemeaua).[36] In 1894, and again in 1897, he and poet Radu D. Rosetti published the literary weekly Doina, named after the singing style. For a while in 1903, with Emil Conduratu, he put out another magazine, Ilustrațiunea Română ("Romanian Illustration").[37]

World War I and Bessarabia

[edit]A secretary of the prototype Romanian Writers' Society during its first meetings of 1908,[38] Dauș cut off his links with the Literatorul circle. In 1912, he was writing for Floare Albastră, the anti-Symbolist review put out at Iași by A. L. Zissu.[39] Early that same year, he had returned with a volume comprising some thirty novellas, under the shared title Satana ("Satan"). As noted by the contemporary reviewer Iosif Nădejde, these works showed that he had never slipped out of his "youthful romanticism". He used his imagination in depicting scenes of extreme misery, and proposed happy endings that already appeared as implausible.[40] After 1914, Dauș became a legal expert for the common land department of the Domains Ministry.[13] He also contributed a poetry collection, În zări de foc ("Toward Fiery Horizons"), which came out in 1915, and with translations of Gustave Flaubert—Salammbô in 1913, Madame Bovary in 1915.[4] Hailed by some scholars as Romania's best Flaubertian translator,[41] he also did a Romanian version of Coppée's Grève de forgerons, which was being recited in public venues by 1926, and which poet Cincinat Pavelescu viewed as "outstanding".[42]

In late 1916, Romania entered World War I, but was invaded by the Central Powers. In October 1916, his poem honoring the dead of Turtucaia was hosted in Viitorul newspaper and then in George Coșbuc's Albina.[43] With Bucharest occupied by the Germans, Dauș fled to Iași, where the Romanian administration had relocated.[22] During that time, he translated stories by the Countess of Ségur.[21] Late in the war, his career became focused on Bessarabia, which had recently united with Romania, and he served as founding director (from 1918) of the Chișinău National Theater.[44] His early activities in that region included his presence at a literary festival held in May 1919 at Chișinău, whereby he commemorated his colleague, the poet and war hero Mihail Săulescu.[45] Overall, Dauș declared himself especially impressed by the "superstitious" religiousness and aristocratic dignity of Bessarabian peasants, becoming a champion of their case.[46] In 1920, some of his new poetry was hosted in the local journal, Vulturul Basarabean.[36]

During his stays in Bucharest, Dauș began frequenting with the modernist salon Sburătorul from its inception in 1919 and also published with regularity in the eponymous magazine.[47] However, according to colleague I. Peltz, he was only welcomed there with "kind condescension" by the Sburătorul house critic, Eugen Lovinescu;[48] the same point was stressed by literary historian Eugen Simion, who sees Dauș as one of the Sburătorists who mainly contributed "utterly commonplace" poems, testing Lovinescu's patience.[49] Within this club, Dauș mainly associated with older figures, including Alexandru Văitoianu and Hortensia Papadat-Bengescu.[50] Nicolae Steinhardt, who began attending Sburătorul sessions on Câmpineanu Street in 1929, chanced upon Dauș and his wife, whom he recalled as a "stale" and underwhelming presence.[51] This positioning also reflected Lovinescu's verdicts: he describes Dauș as a neo-romantic in the proximity of Sămănătorul traditionalism.[52]

Active politically, Dauș joined the minor Independent Party of Bessarabia, established by Iustin Frățiman, Sergiu Niță, and Constantin Stere, running on its lists during the election of November 1919.[53] He went on to serve in Greater Romania's Assembly of Deputies and Senate, attending Inter-Parliamentary Union conferences.[54] He favored a radical land reform that reflected Socialist-Revolutionary influence, excoriating the Bessarabian Peasants' Party for moderating such promises, and singling out Ion Buzdugan and Ion Inculeț as traitors of the peasants.[46] Rallying with the National Liberals, and serving in the Senate during the 1922–1926 legislature, Dauș spoke out for Bessarabian and nationalist causes. Noting the hostile Romanian–Soviet relations, he favored annexing the Moldavian ASSR to Greater Romania.[55] In September 1926, his connections with Bessarabia were severed, as Ion Livescu took over his managerial position at the region's National Theater. The troupe protested at the time, demanding that Dauș be reinstated.[56] These incidents closely followed a clash between the actor Anghelescu and Dauș, during which the latter had fired a revolver; in October 1926, Dauș was facing prosecution by the Chișinău Tribunal.[57]

Literary prominence and related scandals

[edit]Reenlisted by the Writers' Society, Dauș stood out for his criticism of that syndicate. According to his colleague Radu Boureanu, his performance there was awkward: "Sanguine, hotheaded, his logic buried under convoluted arguments voiced in a shrill tone, [Dauș] managed to annoy people by missing out on his opportunity to describe what was vulnerable or unclear in the Society's situation and management."[58] Dauș was also director of the State Press, president of the Romanian Athenaeum and of the Bessarabian Press Association, and eventually deputy director of the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Company.[4][59] He returned to publishing first as a poet, with the 1919 Valea Albă ("White Valley")—a dramatic poem about the eponymous battle of 1476; and the 1924 Drumul sângelui ("Trail of Blood"). The latter was an homage to the soldiers dead at Mărășești and elsewhere on the Romanian front.[60] Dauș's translations of verse drama included Victor Hugo Le roi s'amuse and William Shakespeare's King Lear (both 1924).[4] He continued in that field with a new play centered on, and named after, Vlad Țepeș, performed at the Bucharest National Theater and published in 1930. It earned notoriety and disgust with its depictions of medieval cruelty, including impalement and death by boiling; reviewer Mihail Sevastos sarcastically noted that Dauș only "stopped short of cutting off the actresses' breasts" and never dramatized Vlad's alleged raping by Mehmed the Conqueror. Also according to Sevastos, the play was political theater, urging for the return of a Vlad-like dictator.[61]

Dauș's interwar prose drew more attention, and is generally seen as much more accomplished than his earlier output. According to Crohmălniceanu, his novels of the 1920s and '30s were "interesting, commendable for their social observation", with "an actual writer's skill."[31] According to Lovinescu, Dauș only discovered his literary point of view "at the age when most others lose theirs."[52] The series includes 1927's Drăceasca schimbare de piele ("A Devilish Shedding of the Skin"), in which a middle-aged woman embraces marital infidelity, then insanity, as she changes into the clothes of a courtesan.[62] Among the reviewers of the time, Constantin Șăineanu was largely unimpressed, reading Drăceasca schimbare... as an implausible "exceptional, abnormal, sickly case, to be addressed by medical clinics." The eroticized episodes, Șăineanu argues, "are supposed to pass for action."[63]

Published in 1932, Asfințit de oameni ("A Dimming of Men") documented the decline of boyardom, replaced by "a social mix of Levantines", depicted "with remarkable objectivity and astuteness".[31] As noted by Călinescu, the upstart and murderer Vangheli Zionis, originally the antagonist, appears more likeable by the end of the book, when he is contrasted with the sadistic boyaress Nathalie Dragnea. Based on "romanticized historical truth", the novel is "not entirely transfigured by art".[64] The book was submitted for review by the staff of Viața Romînească magazine, including Sevastos. The latter was indignant, calling it "unpublishable"; as he notes, the group sent the manuscript back and, though the Viața Romînească was facing financial ruin, also rejected Dauș's offer of paid advertising.[65] In that context, Lovinescu was more lenient toward Asfințit de oameni. Highlighting its narrative of class conflict, he sees the novel as a revamped Sămănătorist work, but "solid, realistic, honest", and "without romantic rhetoric."[66]

A final novel, titled O jumătate de om ("Half a Man"), came out in 1937. Dauș personally presented this work, published by Adevărul, to Iorga, believing that the historian and critic would be pleased. Iorga instead panned it, being outraged by the alternation of "banal observations" and "revolting" details of love affairs, including "those parts of the body that humans cover up in their effort to seem less like dogs."[67] Noted by Crohmălniceanu for its "ingenious intrigue" and its "nervous" writing,[68] O jumătate de om follows the submissive and exploitable Traian Belciu through a series of existential failures. These culminate with him being swept up by the world war, dragged into Germanophile circles, and ultimately shot as a deserter. It is, in Lovinescu's view, the best book by Dauș—accomplished as a work of political fiction, but largely failed as a psychological novel, and out of step with modernism.[66] Among the modernist critics, Octav Șuluțiu defended O jumătate de om as a Romanian adaptation of the English novel; he also noted many coincidental similarities between Belciu and Costel Petrescu, the protagonist of Papadat-Bengescu's Logodnicul.[69] According to Iorga, Dauș made no effort to conceal that some of the characters in the book were identifiable among the intellectual class of Botoșani.[70]

In tandem with this controversy, Dauș's activity as a translator expanded to cover works by Honoré de Balzac (a version of Eugénie Grandet came out in 1935). His parallel translations from Heine were put to music by the Transylvanian Emil Monția.[21] He also worked on a stage adaptation of Frank Swinnerton's novel, Nocturne, which garnered praise upon its production by Comoedia Theater in August 1936.[71] Having been awarded the Writers' Society prize in 1938,[4][38] the following year he put out memoirs in the magazine Jurnalul Literar.[72] Also in 1939, upon Gherman Pântea's invitation, he returned to Bessarabia to unveil a monument honoring Ferdinand I of Romania, using the occasion to reinforce unionist sentiment with a patriotic speech.[73] As an associate of Victor Dombrovski, the Mayor of Bucharest, Dauș helped organize the June 1939 commemoration of Mihai Eminescu, Romania's national poet,[10] to whom he dedicated several speeches and poems.[74] The following year, he joined Corneliu Moldovanu and Horia Oprescu in editing works by the Romanian classics, published at the city hall's expense.[75] Such cultural efforts were repeated in early June 1940, when Dombrovski organized the Luna Bucureștilor festival, which had Dauș as one of the four commissioners.[76]

Later life

[edit]Also in June 1940, Romania unexpectedly lost Bessarabia to a Soviet invasion. In the aftermath, Dauș appeared at a Writers' Society function in Bucharest, gathering funds for the Bessarabian refugees. Introduced by Glasul Bucovinei newspaper as the "grey-haired nationalist fighter on the fields of justice and writing", he was visibly emotional as he recited his own verse.[77] In November 1941, months after Romania had joined in Operation Barbarossa and had managed to recover Bessarabia, he contributed to Viața Basarabiei of Chișinău—that celebratory issue proposed extending the Romanian dominion by fully annexing Transnistria Governorate.[78] Dauș's final works, published later during World War II, were the play Ioana (1942) and the novella collection Porunca toamnei ("Autumn Commands", 1943).[4] The former was performed at Bucharest's Studio Theater (a subsidiary of the National Theater), and had considerable success,[41] but was poorly regarded by critics. Ioan Massoff noted in 1980 that the effort had been commendable, but overall failed.[79] Himself a playwright, Alexandru Kirițescu decried Ioana as a throwback to "salon drama" as cultivated by Haralamb Lecca. The genre, he noted, "requires neither observational skill nor wit".[80] Originally about the Romanian War of Independence, Ioana was modified just before the staging, and adapted to the war-torn 1940s.[80] The eponymous heroine Ioana Goiu is, like Dauș himself, an aristocrat from Costache Negri's family; she is also a stereotypical ingénue, the only person moral enough to stand up against the machinations of a Bessarabian confidence man, Grișa, who is spying on her father's arms-making business.[80][81]

In early 1943, at the height of Romania's participation as an Axis county on the Eastern Front, the National Theater Bucharest was ordered to begin a new production of Valea Albă, with M. Zirra as director. According to Massoff, this was a display "patriotic, but also chauvinistic ideas", with "all to glaring" hints about the "events of the day".[82] Dauș presented a new manuscript play, Drum întors ("The Way Back"), but the theatrical committee refused to run it, sending it back in October 1943. The attached note indicated that "the social and political content of the play [are] utterly inopportune, given the current events".[83] Shortly after King Michael's Coup in August 1944, Dombrovski returned as Mayor of Bucharest. Consequently, Dauș was made co-director of Caragiale Theater, sharing this distinction with actor Ion Manolescu and producer Sică Alexandrescu.[84]

Shortly after the coup, a novelist colleague and fellow theatrical manager, Liviu Rebreanu, politically compromised as an alleged supporter of the outgoing regime, had fallen ill with a lung cyst,[85] later revealed to have been cancer.[86] Dauș helped his colleague, transporting Rebreanu to Valea Mare, and becoming one of the people who nursed him there; he also witnessed Rebreanu's final moments.[85] During his stay there, the area witnessed sporadic fighting between Romanian troops and the Wehrmacht.[86] It was also Dauș who successfully obtained that Rebreanu's remains be transported to Bucharest and reburied at Bellu cemetery.[87] He himself lived to see the first years of Romanian communist rule, being inducted into the new Writers' Union of Romania in 1949.[2] He ultimately died in Bucharest.[30] Some confusion persists as to the date, with several sources indicating 1953 as his death year;[4][88] the most precise accounts indicate that he died on November 17, 1954.[2][13] He was laid to rest two days after at a cemetery in Colentina.[13]

Legacy

[edit]Dauș left various manuscripts, including a verse chronicle of World War II, titled Anii cerniți ("Years of Mourning"), and the unfinished novel Răscruci ("Junctions").[89] At least three other notebooks of his own poetry, and an "impressive number" of poetry translations (notably, from Charles Baudelaire, Alexander Pushkin, and Paul Verlaine), all remain unpublished.[90] He was survived by his widow Ecaterina Thiéry-Dauș, who donated his papers and her own memoirs of their life together to the National Archives fund in Botoșani.[91] In 1977, critic Valentin Tașcu noted that the "solid tradition of Romanian historical prose" included Rebreanu, Mihail Sadoveanu, Camil Petrescu, "and even Ludovic Dauș."[92]

In an April 1979 article for Contemporanul, critic Henri Zalis proposed Dauș as an author who needed to be rediscovered—and noted that Rebreanu himself had apparently enjoyed Dauș's writings. Zalis added: "And yet, ever since the Liberation [of August 1944], Dauș has remained 'hidden' among the under-performers."[93] In August 1981, researcher Nicolae Liu summarized one of the Dauș manuscripts (detailing his time nursing Rebreanu, and his defense of the latter against accusations of Nazism) for Luceafărul magazine. Liu spoke of Dauș himself as having been "unduly forgotten".[85] As argued by scholar Iurie Colesnic, while dismissed as a "mediocre" writer and "almost forgotten" in Romania, Dauș is still regarded as a "legendary figure" among the Romanians of Bessarabia—in particular, in the present-day Republic of Moldova.[94]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Naghiu, pp. 527, 528

- ^ a b c d e f g Ștefan Cervatiuc, "De la A la Z. 22. Dauș Ludovic", in Clopotul, June 24, 1973, p. 2

- ^ Călinescu, p. 920; Gancevici, p. 364

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ion Simuț, "Dauș Ludovic", in Aurel Sasu (ed.), Dicționarul biografic al literaturii române, Vol. I, pp. 457–458. Pitești: Editura Paralela 45, 2004. ISBN 973-697-758-7

- ^ Gancevici, p. 364; Naghiu, p. 527

- ^ a b c d "Desbaterile Adunării Deputaților", in Monitorul Oficial, Issue 39/1896, pp. 569–570

- ^ Gancevici, p. 364. See also Naghiu, p. 527

- ^ a b Călinescu, p. 920

- ^ "Din țară. Bătaie între funcționarĭ", in Epoca, July 2, 1897, p. 2; "Un fel de falș în acte publice", in Epoca, August 1, 1897, p. 3

- ^ a b c Gancevici, p. 364

- ^ Călinescu, p. 920; Naghiu, p. 528

- ^ Gancevici, pp. 364, 365; Naghiu, pp. 527, 528

- ^ a b c d Naghiu, p. 528

- ^ Gancevici, pp. 364, 365–366

- ^ Călinescu, p. 920; Colesnic, p. 210

- ^ Ioan Bacalbașa, "Cronică teatrală. Teatrul Național: Noblețea nouă și Noblețea veche—reluare.—Steaua, dramă într'un act în versuri de A. Gill și I. Richepin, tradusă de d. Radu D. Rosetti.—Iacobițiǐ, dramă în 5 acte în versurĭ de Fr. Copée, tradusă de d. Ludovic Dauș", in Lupta, October 24, 1895, p. 1

- ^ Călinescu, p. 920; Naghiu, p. 527

- ^ Călinescu, p. 920. See also Colesnic, p. 210

- ^ Călinescu, p. 920. See also Naghiu, p. 528

- ^ Călinescu, pp. 592, 919. See also Colesnic, p. 211

- ^ a b c Naghiu, p. 531

- ^ a b Ludovic Dauș, "Amintiri despre Haralamb Lecca", in Universul Literar, Issue 36/1929, p. 363

- ^ "Scirile d̦ileĭ. Serbarea aniversăreĭ regineĭ Românieĭ", in Gazeta Transilvaniei, Issue 281/1901, p. 2

- ^ Călinescu, pp. 919, 1026; Gancevici, p. 366. See also Colesnic, p. 211; Crohmălniceanu, p. 340

- ^ Gancevici, p. 366

- ^ Valeriu Cristea, "O conștiință nouă", in România Literară, Issue 33/1981, p. 11

- ^ Mihăilescu, p. 62

- ^ Regist., "Voința și direcția Teatruluĭ Național. — Lucrurĭ nostime", in Adevărul, December 1, 1903, p. 3

- ^ Călinescu, p. 1026; Crohmălniceanu, p. 340; Gancevici, pp. 365–367

- ^ a b Gancevici, p. 365

- ^ a b c Crohmălniceanu, p. 340

- ^ Mihăilescu, p. 60

- ^ Iorga (1934), p. 13

- ^ Colesnic, p. 211; Naghiu, p. 529

- ^ Naghiu, pp. 529, 531

- ^ a b Colesnic, p. 211

- ^ Naghiu, p. 529

- ^ a b Victor Durnea, "Societatea scriitorilor români", in Dacia Literară, Issue 2/2008

- ^ Iorga (1934), p. 243

- ^ Iosif Nădejde, "Cărți și reviste. Satana, de Ludovic Dauș. — Higiena, revistă bilunară", in Adevărul, February 20, 1912, p. 1

- ^ a b Gancevici, p. 367

- ^ Ștefan Cervatiuc, "Clopotul cultural-artistic. Arhiva. Ludovic Dauș", in Clopotul, April 15, 1973, p. 2

- ^ Ludovic Dauș, "Turtucaia", in Albina. Revistă Enciclopedică Populară, Issues 1–2/1916, p. 6

- ^ Colesnic, pp. 210–211; Gancevici, pp. 364–365

- ^ "Informațiuni. Din Chișinău", in Glasul Bucovinei, May 14, 1919, p. 2

- ^ a b Colesnic, p. 213

- ^ Eugen Lovinescu, "Sburătorul Literar" (manifesto), in Sburătorul Literar, Issue 1/1921, p. 1

- ^ Peltz, p. 89

- ^ Eugen Simion, "Momente de climat cultural. Sburătorul", in Ramuri, Issue 11/1967, p. 10

- ^ Peltz, pp. 85–86, 89, 108

- ^ Nicolae Steinhardt, "Cărți — oameni — fapte. Nu departe de E. Lovinescu", in Viața Românească, Issue 7/1981, p. 87

- ^ a b Lovinescu, p. 195

- ^ Svetlana Suveică, Basarabia în primul deceniu interbelic (1918–1928): modernizare prin reforme. Monografii ANTIM VII, p. 67. Chișinău: Editura Pontos, 2010. ISBN 978-9975-51-070-7

- ^ Gancevici, p. 365; Naghiu, p. 528

- ^ Radu Filipescu, "Românii transnistreni în dezbaterile Parlamentului României (1919–1937)", in Acta Moldaviae Septentrionalis, Vol. X, 2011, pp. 217, 219

- ^ Colesnic, p. 222

- ^ "Procesul d-lui Ludovic Dauș", in Lupta, October 17, 1926, p. 3

- ^ Radu Boureanu, "La moartea lui Darie", in Viața Românească, Issue 12/1974, p. 16

- ^ Călinescu, p. 920; Gancevici, pp. 364–365. See also Naghiu, p. 528

- ^ Gancevici, pp. 365, 367. See also Naghiu, p. 529–530

- ^ Mihail Sevastos, "Cronica teatrală", in Viața Romînească, Issue 2/1931, pp. 187–188

- ^ Crohmălniceanu, p. 340; Lovinescu, pp. 195–196; Șăineanu, pp. 108–109

- ^ Șăineanu, p. 109

- ^ Călinescu, pp. 919–920; Colesnic, p. 211. See also Gancevici, p. 366

- ^ Mihail Sevastos, Amintiri de la Viața românească, p. 376. Bucharest: Editura pentru literatură, 1966

- ^ a b Lovinescu, p. 196

- ^ Iorga (1936), p. 625

- ^ Crohmălniceanu, p. 341

- ^ Octav Șuluțiu, "Scriitori și cărți. Ludovic Dauș: O jumătate de om (Ed. Adevărul)", in Familia, Vol. IV, Issues 6–7, June–July 1937, pp. 90–92

- ^ Iorga (1936), p. 626

- ^ S. Podoleanu, "Plimbări prin teatrele de vară. Nocturna de Ludovic Dauș, la teatrul 'Comoedia' ca plafonul ridicat", in Rampa, August 5, 1936, p. 1

- ^ Călinescu, p. 1026; Colesnic, p. 211

- ^ Colesnic, pp. 211–212

- ^ Naghiu, p. 529, 529, 530–531

- ^ Constantin Virgil Gheorghiu, "Tipar de lux", in Timpul, June 30, 1940, p. 2

- ^ "Inaugurarea 'Lunei Bucureștilor' 1940. Asistența", in Timpul, June 9, 1940, p. 16

- ^ "Șezătoarea Scriitorilor Români în folosul refugiaților", in Glasul Bucovinei, July 17, 1940, p. 1

- ^ "Revista revistelor. Bugul, 'granița politică de răsărit a României'. Viața Basarabiei — Anul X — Nr. 11–12—Noemvrie–Decemvrie 1941", in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Vol. IX, Issue 3, March 1942, p. 697

- ^ Massoff, p. 137

- ^ a b c Alexandru Kirițescu, "Viața Teatru. Cronica teatrală. Studio: Ioana, piesă în 3 acte de Ludovic Dauș", in Viața, October 19, 1942, p. 2

- ^ Massoff, pp. 137–138

- ^ Massoff, pp. 157–158

- ^ Massoff, p. 194

- ^ Lucian Sinigaglia, "Universul teatral bucureștean și politicile culturale după 23 august 1944. Amurgul teatrului burghez (I)", in Studii și Cercetări de Istoria Artei. Teatru, Muzică, Cinematografie, Vol. 7–9 (51–53), 2013–2015, p. 47. See also Massoff, p. 265

- ^ a b c Nicolae Liu, "O mărturie inedită despre sfârșitul lui Liviu Rebreanu", in Luceafărul, Vol. XXIV, Issue 32, August 1981, p. 3

- ^ a b Augustin Buzura, "Amurgul lui Rebreanu", in Tribuna, Vol. IX, Issue 48, December 1965, p. 8

- ^ Horia Oprescu, "Liviu Rebreanu cel necunoscut...", in Tribuna, Vol. 1, Issue 17, June 1957, p. 7

- ^ Colesnic, p. 212

- ^ Naghiu, pp. 530, 532

- ^ Gancevici, pp. 365, 367–368. See also Naghiu, p. 531

- ^ Naghiu, pp. 527, 532

- ^ Valentin Tașcu, "Arheologia spiritului sau proza istorică", in Steaua, Vol. XXVIII, Issue 1, January 1977, p. 2

- ^ Henri Zalis, "Uitați pe nedrept", in Contemporanul, Issue 16/1979, p. 9

- ^ Colesnic, pp. 212–213

References

[edit]- George Călinescu, Istoria literaturii române de la origini pînă în prezent. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1986.

- Iurie Colesnic, Chișinăul din inima noastră. Chișinău: B. P. Hașdeu Library, 2014. ISBN 978-9975-120-17-3

- Ovid Crohmălniceanu, Literatura română între cele două războaie mondiale, Vol. I. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1972. OCLC 490001217

- Maria Gancevici, "Contribuții la viața și opera lui Ludovic Dauș", in Hierasus, Vol. II, 1979, pp. 364–369.

- Nicolae Iorga,

- Istoria literaturii românești contemporane. II: În căutarea fondului (1890–1934). Bucharest: Editura Adevĕrul, 1934.

- "Inca un molipsit: d. Ludovic Dauș", in Cuget Clar, Vol. I, 1936–1937, pp. 625–626.

- Eugen Lovinescu, Istoria literaturii române contemporane. Chișinău: Editura Litera, 1998. ISBN 9975740502

- Ioan Massoff, Teatrul românesc: privire istorică. Vol. VIII: Teatrul românesc în perioada 1940—1950. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1981.

- Dan C. Mihăilescu, "Permanența clasicilor. I. L. Caragiale în lumea lui Claymoor", in Viața Românească, Issue 12/1988, pp. 58–64.

- Iosif E. Naghiu, "Contribuții la biografia lui Ludovic Dauș (1873—1954)", in Hierasus. Anuar '78, Part I, pp. 527–532.

- I. Peltz, Amintiri din viața literară. Bucharest: Cartea Românească, 1974. OCLC 15994515

- Constantin Șăineanu, Noui recenzii: 1926–1929. Bucharest: Editura Adevĕrul, 1930. OCLC 253127853

- 1873 births

- 1954 deaths

- 19th-century Romanian novelists

- 20th-century Romanian novelists

- Romanian historical novelists

- Psychological fiction writers

- Romanian erotica writers

- Romanian male short story writers

- Romanian short story writers

- Romanian poets

- Romanian dramatists and playwrights

- Romanian theatre managers and producers

- Romanian translators

- French–Romanian translators

- English–Romanian translators

- Russian–Romanian translators

- Translators of Gustave Flaubert

- Translators of Alexander Pushkin

- Translators of William Shakespeare

- Translators of Leo Tolstoy

- Romanian book publishers (people)

- Adevărul writers

- Romanian magazine founders

- Romanian magazine editors

- 20th-century Romanian lawyers

- Romanian civil servants

- Romanian nationalists

- Romanian monarchists

- Romanian agrarianists

- National Liberal Party (Romania) politicians

- Members of the Chamber of Deputies (Romania)

- Members of the Senate of Romania

- People from Botoșani

- Romanian people of Czech descent

- Members of the Romanian Orthodox Church

- Naturalised citizens of Romania

- Romanian nobility

- A. T. Laurian National College alumni

- University of Bucharest alumni

- Romanian World War I poets

- Romanian people of World War II