List of countries in the Eurovision Song Contest

Broadcasters from fifty-two countries have participated in the Eurovision Song Contest since it started in 1956, with winning songs coming from twenty-seven of those countries. The contest, organised by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), is held annually between members of the union who participate representing their countries. Broadcasters submit songs to the event where they are performed live by the performer(s) they had selected and cast votes to determine the winning song of the competition.

Participation in the contest is primarily open to all broadcasters with active EBU membership, with only one entrant per country allowed in any given year. To become an active member of the EBU, a broadcaster has to be from a country which is covered by the European Broadcasting Area –that is not limited only to the continent of Europe–, or is a member state of the Council of Europe.[1] Thus, eligibility is not determined by geographic inclusion within Europe, despite the "Euro" in "Eurovision", nor does it have a direct connection with the European Union. Several countries geographically outside the boundaries of Europe have been represented in the contest: Israel, and Armenia, in Western Asia, since 1973 and 2006 respectively; Morocco, in North Africa, in the 1980 competition alone; and Australia making a debut in the 2015 contest. In addition, several transcontinental countries with only part of their territory in Europe have been represented: Turkey, from 1975 to 2012; Russia, from 1994 to 2021; Georgia, since 2007; and Azerbaijan, which made its first appearance in the 2008 edition. Two of the countries that have previously sought to enter the competition, Lebanon and Tunisia, in Western Asia and North Africa respectively, are also outside of Europe. A broadcaster from the Persian Gulf state of Qatar, in Western Asia, announced in 2009 its interest in joining the contest in time for the 2011 edition.[2] However, this did not materialise, and there are no known plans for a future Qatari entry. Australia, where the contest has been broadcast since the 1970s, has been represented every year since its debut in 2015, as its broadcaster is an EBU associate member and had received special approval from the contest's Reference Group.

The number of countries represented each year has grown steadily, from seven in 1956 to over twenty in the late 1980s. A record forty-three countries participated in 2008, 2011, and 2018. As the number of contestants has risen, preliminary competitions and relegation have been introduced, to ensure that as many countries as possible get the chance to compete. In 1993, a preliminary show, Kvalifikacija za Millstreet ("Qualification for Millstreet"), was held to select three Eastern European countries to compete for the first time in the main contest.[3] After the 1993 contest, a relegation rule was introduced: the six lowest-placed countries in the contest would not compete in the following year.[4] In 1996, a new system was introduced. Audiotapes of all twenty-nine entrants were submitted to national juries. The twenty-two highest-placed songs after the juries voted reached the contest. Norway, as the host country, directly qualified for the final.[5] From 1997 to 2001, a system was used whereby the countries with the lowest average scores over the previous five years were relegated. Countries could not be relegated for more than one year at a time.[6]

The relegation system used in 1994 and 1995 was used again between 2001 and 2003. Since 1999, the winning country in the previous year's contest automatically qualifies for the following year's final, along with the "Big Four/Five" — those countries whose broadcasters are the largest financial contributors to the EBU.[a] In 2004, a semi-final was introduced. In addition to the Big Four, the countries that were in the top 10 the previous year received a bye and qualified directly for the final. A further ten countries qualified from the semi-final, making a total of 24 in the final.[7] Since 2008, two semi-finals are held with all countries, except the previous year's winner and the "Big Four/Five", participating in one of the semi-finals.[8]

Some countries, such as Germany, France, Belgium, and the United Kingdom, have entered most years, while Morocco has only entered once. Two countries, Tunisia and Lebanon, have attempted to enter the contest but withdrew before making a debut.

Participants

[edit]The following table lists the countries with a broadcaster that have participated in the contest at least once, up to 2023. Planned entries for the cancelled 2020 contest and entries that failed to qualify in the qualification rounds in 1993 or 1996 are not counted.

Shading indicates countries whose broadcaster have withdrawn from the contest or former participants that are unable to compete in future contests. Yugoslavia and Serbia and Montenegro were both dissolved, in 1991 and 2006 respectively. Serbia and Montenegro participated in the 1992 contest as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which consisted of only those two republics. Montenegro and Serbia have each competed as separate countries since 2007.[9] The Belarusian broadcaster BTRC was expelled from the EBU in July 2021, preventing them from competing in future editions of the contest, or any EBU event indefinitely.[10] Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent exclusion of Russia from the 2022 contest, the Russian broadcasters VGTRK and Channel One announced their intention to withdraw their EBU membership in February 2022 and were suspended from the union in May, preventing Russia from competing in future editions of the contest, or any EBU event for an indefinite period of time.[11]

| † | Inactive – countries which participated in the past but did not appear in the most recent contest, or will not appear in the upcoming contest |

| ◇ | Ineligible – countries whose broadcasters are no longer part of the EBU and are therefore ineligible to participate |

| ‡ | Former – countries which previously participated but no longer exist |

| Country | Broadcaster(s)[12] | Debut year | Latest entry | Entries | Finals | Times qualified | Qualifying rate | Latest final | Wins | Latest win |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RTSH | 2004 | 2024 | 20 | 11 | 10/19 | 53% | 2023 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTVA | 2004 | 2009 | 6 | 0 | 0/6 | 0% | N/A | 0 | N/A | |

| AMPTV | 2006 | 2024 | 16 | 13 | 12/15 | 80% | 2024 | 0 | N/A | |

| SBS | 2015 | 2024 | 9 | 7 | 6/8 | 75% | 2023 | 0 | N/A | |

| ORF | 1957 | 2024 | 56 | 49 | 7/14 | 50% | 2024 | 2 | 2014 | |

| İTV | 2008 | 2024 | 16 | 13 | 12/15 | 80% | 2022 | 1 | 2011 | |

| BTRC | 2004 | 2019 | 16 | 6 | 6/16 | 38% | 2019 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTBF[c] / VRT[d] | 1956 | 2024 | 65 | 54 | 8/19 | 42% | 2023 | 1 | 1986 | |

| BHRT[e] | 1993 | 2016 | 19 | 18 | 7/8 | 88% | 2012 | 0 | N/A | |

| BNT | 2005 | 2022 | 14 | 5 | 5/14 | 36% | 2021 | 0 | N/A | |

| HRT | 1993 | 2024 | 29 | 20 | 8/17 | 47% | 2024 | 0 | N/A | |

| CyBC | 1981 | 2024 | 40 | 33 | 11/18 | 61% | 2024 | 0 | N/A | |

| ČT | 2007 | 2024 | 12 | 5 | 5/12 | 42% | 2023 | 0 | N/A | |

| DR | 1957 | 2024 | 52 | 44 | 10/18 | 56% | 2019 | 3 | 2013 | |

| ERR[g] | 1994 | 2024 | 29 | 19 | 10/20 | 50% | 2024 | 1 | 2001 | |

| Yle | 1961 | 2024 | 57 | 49 | 11/19 | 58% | 2024 | 1 | 2006 | |

| France Télévisions[h] | 1956 | 2024 | 66 | 66 | Automatic qualifier[i] | 2024 | 5 | 1977 | ||

| GPB | 2007 | 2024 | 16 | 8 | 8/16 | 50% | 2024 | 0 | N/A | |

| ARD (NDR)[j] | 1956 | 2024 | 67 | 67 | Automatic qualifier[i] | 2024 | 2 | 2010 | ||

| ERT[k] | 1974 | 2024 | 44 | 41 | 14/17 | 82% | 2024 | 1 | 2005 | |

| MTVA[l] | 1994 | 2019 | 17 | 14 | 10/13 | 77% | 2018 | 0 | N/A | |

| RÚV | 1986 | 2024 | 36 | 27 | 10/19 | 53% | 2022 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTÉ[m] | 1965 | 2024 | 57 | 46 | 7/18 | 39% | 2024 | 7 | 1996 | |

| IPBC[n] | 1973 | 2024 | 46 | 39 | 11/18 | 61% | 2024 | 4 | 2018 | |

| RAI | 1956 | 2024 | 49 | 49 | Automatic qualifier[i] | 2024 | 3 | 2021 | ||

| LTV | 2000 | 2024 | 24 | 11 | 6/19 | 32% | 2024 | 1 | 2002 | |

| LRT | 1994 | 2024 | 24 | 17 | 12/19 | 63% | 2024 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTL[o] | 1956 | 2024 | 38 | 38 | 1/1 | 100% | 2024 | 5 | 1983 | |

| PBS[p] | 1971 | 2024 | 36 | 26 | 8/18 | 44% | 2021 | 0 | N/A | |

| TRM | 2005 | 2024 | 19 | 13 | 12/18 | 67% | 2023 | 0 | N/A | |

| TMC[q] | 1959 | 2006 | 24 | 21 | 0/3 | 0% | 1979 | 1 | 1971 | |

| RTCG | 2007 | 2022 | 12 | 2 | 2/12 | 17% | 2015 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTM[r] | 1980 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 1980 | 0 | N/A | |||

| AVROTROS[s] | 1956 | 2024 | 64 | 53[t] | 9/19 | 47% | 2022[t] | 5 | 2019 | |

| MRT | 1998 | 2022 | 21 | 9 | 6/18 | 33% | 2019 | 0 | N/A | |

| NRK | 1960 | 2024 | 62 | 59 | 14/17 | 82% | 2024 | 3 | 2009 | |

| TVP | 1994 | 2024 | 26 | 16 | 7/17 | 41% | 2023 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTP[v] | 1964 | 2024 | 55 | 46 | 8/17 | 47% | 2024 | 1 | 2017 | |

| TVR | 1994 | 2023 | 23 | 19 | 11/15 | 73% | 2022 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTR / C1R[w] | 1994 | 2021 | 23 | 22 | 11/12 | 92% | 2021 | 1 | 2008 | |

| SMRTV | 2008 | 2024 | 14 | 3 | 3/14 | 21% | 2021 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTS | 2007 | 2024 | 16 | 13 | 12/15 | 80% | 2024 | 1 | 2007 | |

| UJRT | 2004 | 2005 | 2 | 2 | 1/1 | 100% | 2005 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTVS[x] | 1994 | 2012 | 7 | 3 | 0/4 | 0% | 1998 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTVSLO | 1993 | 2024 | 29 | 17 | 8/20 | 40% | 2024 | 0 | N/A | |

| RTVE[y] | 1961 | 2024 | 63 | 63 | Automatic qualifier[i] | 2024 | 2 | 1969 | ||

| SVT[z] | 1958 | 2024 | 63 | 62 | 13/14 | 93% | 2024 | 7 | 2023 | |

| SRG SSR | 1956 | 2024 | 64 | 53 | 8/19 | 42% | 2024 | 3 | 2024 | |

| TRT | 1975 | 2012 | 34 | 33 | 6/7 | 86% | 2012 | 1 | 2003 | |

| UA:PBC[aa] | 2003 | 2024 | 19 | 19 | 14/14 | 100% | 2024 | 3 | 2022 | |

| BBC | 1957 | 2024 | 66 | 66 | Automatic qualifier[i] | 2024 | 5 | 1997 | ||

| JRT | 1961 | 1992 | 27 | 27 | N/A | 1992 | 1 | 1989 | ||

Other EBU members

[edit]The following countries have broadcasters eligible to participate in the contest, but have never done so:

Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, and Tunisia have broadcasters that are members of both the EBU and the Arab States Broadcasting Union (ASBU). Although they could participate, it is believed that they refuse to do so due to the ongoing participation of Israel.[14] However, Tunisia and Lebanon attempted to compete in 1977 and 2005 respectively. Vatican City could participate through its member broadcaster Vatican Radio (RV), which was also a founding member of the EBU, though RV only broadcasts papal events, and the population is less than 900 – the vast majority of whom are clergy.[14][15] Following the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993, Slovakia and the Czech Republic made their debut as independent states in 1994 and 2007 respectively.

Lebanon

[edit]Lebanon has never participated in the Eurovision Song Contest. Télé Liban (TL), was set to make the country's debut at the Eurovision Song Contest 2005 with the song "Quand tout s'enfuit" performed by Aline Lahoud,[16] but withdrew due to Lebanon's laws banning the broadcast of Israeli content.[17]

Scotland

[edit]On 18 December 2018, it was announced that the Scottish Gaelic branch of the BBC, BBC Alba, would debut at Eurovision Choir in 2019, which was held in Gothenburg, Sweden.[18] However, they did not progress beyond the semi-final. This was the first time Scotland had competed separately from the United Kingdom in a Eurovision event.

The Scottish Media Group (STV) is a full EBU member. Its participation in the Eurovision Song Contest would represent Scotland. As in other Eurovision events, it can only happen if the BBC renounces its right to represent the United Kingdom as a whole.

Tunisia

[edit]Établissement de la radiodiffusion-télévision tunisienne (ERTT) attempted to enter the 1977 edition representing Tunisia and was scheduled fourth in the running order; however, before selecting an act, it withdrew for undisclosed reasons.[19][20] It is believed that it did not want to compete with Israel.[20] In 2007, ERTT clarified that it would not participate in the contest in the foreseeable future due to government requests.[19]

Wales

[edit]In the 1960s, the late Welsh singer, scholar, and writer Meredydd Evans proposed that Wales should have its own entry in the Eurovision Song Contest. In 1969, Cân i Gymru was launched by BBC Cymru Wales as a selection show for the contest, with songs to be performed in Welsh. However, it was decided that the BBC would continue to send one entry for the whole of the United Kingdom. Despite this, Cân i Gymru has been broadcast every year since, with the exception of 1973. The winning song takes part in the annual Pan Celtic Festival in Ireland.

Wales has appeared as an independent country in another EBU production, Jeux sans frontières, and Welsh national broadcaster Sianel Pedwar Cymru (S4C), that is a full EBU member, has been encouraged to take part in the Junior Eurovision Song Contest, where it made its debut in 2018, finishing in last place.[21] Wales participated in the inaugural Eurovision Choir in 2017, where it finished second.[22] The country is also eligible to take part in the minority language song contest Liet-Lávlut. In May 2024, a campaign was started by record label Coco & Cwtsh – to which Cân i Gymru winner Sara Davies is signed – for Wales to participate in the Eurovision Song Contest; however, as in other Eurovision events, this can only happen if the BBC renounces to its right to represent the United Kingdom as a whole.[23]

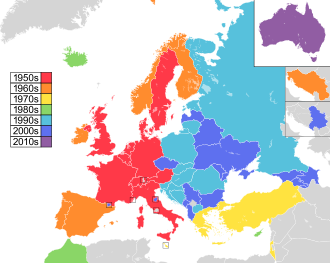

Participating countries by decade

[edit]

The table lists the participating countries in each decade since the first Eurovision Song Contest was held in 1956.

Seven countries participated in the first contest. Since then, the number of entries has increased steadily. In 1961, three countries debuted, Finland, Spain, and Yugoslavia, joining the thirteen already included. Yugoslavia would become the only socialist country to participate in the following three decades. In 1970, a Nordic-led boycott of the contest reduced the number of countries entering to twelve.[24] By the late 1980s, over twenty countries had become standard.

In 1993, the collapse of the USSR in Eastern Europe and the subsequent merger of EBU and the International Radio and Television Organisation (OIRT) gave numerous broadcasters from new countries the opportunity to compete. Three countries—Croatia, Slovenia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, all of them former Yugoslav republics—went through a pre-qualifier round to compete. After the 1993 event, a relegation system was introduced, allowing more Eastern European countries to compete, with seven more making their debut in 1994.

In 2003, broadcasters from four countries applied to make their debut: Albania, Belarus, Bulgaria, and Ukraine. In addition, Serbia and Montenegro, who had not competed since 1992 when they competed as Yugoslavia, applied to debut. The EBU, having originally accepted the five countries' applications, later rejected all but Ukraine; allowing five further countries to compete would have meant relegating too many countries.[25][26] The semi-final was introduced in 2004 in an attempt to prevent situations like this. The EBU set a limit of forty countries,[27] but by 2005, thirty-nine were competing. In 2007, the EBU lifted the limit, allowing forty-two countries to compete. Two semi-finals were held for the first time in 2008.[8]

# |

Debutant | The country made its debut during the decade. |

1 |

Winner | The country won the contest. |

2 |

Second place | The country was ranked second. |

3 |

Third place | The country was ranked third. |

X |

Remaining places | The country placed from fourth to second last in the final. |

◁ |

Last place | The country was ranked last in the final. |

W/D |

Withdrawn/disqualified before the contest | The country was to participate in the contest but either withdrew or got disqualified before the contest took place. |

Ð |

Disqualified during the contest | The country had already participated in at least one show but was disqualified before the completion of the contest. |

† |

Non-qualified for the final | The country did not qualify for the final (2004–present). |

‡ |

Non-qualified for the contest | The country did not qualify from the pre-qualifying round (1993, 1996). |

? |

Unknown | The country's placing in the contest is unknown (1956). |

R |

Relegated | The country was relegated from the contest due to poor results in the previous years (1994–1995; 1997–2003). |

C |

Cancelled | The contest was cancelled after the deadline for submitting songs had passed (2020). |

U |

Upcoming | The country has confirmed participation for the next contest, however, the contest has yet to take place. |

| No entry | The country did not enter the contest. |

1956–1959

[edit]| Country | 1956[ad] | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ◁ | X | X | ||

| ? | X | X | X | |

| 3 | X | X | ||

| ? | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| ? | X | X | X | |

| ? | X | 3 | X | |

| ? | X | ◁ | ||

| ◁ | ||||

| ? | 1 | ◁ | 1 | |

| X | X | |||

| 1 | X | 2 | X | |

| X | 2 | |||

1960–1969

[edit]| Country | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | ◁ | ◁ | X | X | X | 1 | X | X | ||

| X | ◁ | ◁ | X | X | ◁ | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | X | 1 | X | X | X | ||||

| X | X | ◁ | X | ◁ | X | X | ◁ | X | ||

| 1 | X | 1 | X | X | 3 | X | 3 | 3 | 1 | |

| X | X | X | X | ◁ | ◁ | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | 2 | X | X | ||||||

| X | X | X | 3 | 1 | X | ◁ | X | X | X | |

| ◁ | 1 | 3 | X | X | 1 | X | X | X | X | |

| 3 | X | 2 | X | 3 | X | ◁ | X | X | X | |

| X | X | ◁ | ◁ | X | X | X | X | ◁ | 1 | |

| X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | 3 | X | X | ◁ | |

| ◁ | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| X | ◁ | X | X | ◁ | X | X | 1 | 1 | ||

| X | X | X | ◁ | X | 2 | X | X | X | ||

| X | 3 | X | 2 | ◁ | X | X | ◁ | X | X | |

| 2 | 2 | X | X | 2 | 2 | X | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | X | X | X | ||

1970–1979

[edit]| Country | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | X | X | X | X | ◁ | |||||

| X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | X | X | 2 | ◁ | |

| X | X | |||||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | X | W | X | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | X | ◁ | X | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| 1 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 3 | X | X | |

| X | X | X | X | X | 1 | 1 | ||||

| X | X | X | X | 2 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| ◁ | X | 1 | 1 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| ◁ | ◁ | W | X | |||||||

| X | 1 | X | X | X | X | 3 | X | X | X | |

| X | X | X | X | 3 | 1 | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | X | ◁ | X | ◁ | X | ◁ | X | ||

| X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| X | 2 | X | 2 | X | X | X | X | X | 2 | |

| X | X | X | 1 | X | ◁ | X | X | |||

| X | X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | X | X | X | |

| W | ||||||||||

| ◁ | X | W | ||||||||

| 2 | X | 2 | 3 | X | 2 | 1 | 2 | X | X | |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

1980–1989

[edit]| Country | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | X | ◁ | X | |

| X | X | X | X | X | ◁ | 1 | X | X | X | |

| X | X | X | X | X | ◁ | X | W | X | ||

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 3 | 3 | |

| ◁ | X | ◁ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| X | 3 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 2 | 2 | 1 | X | X | 2 | X | 2 | X | X | |

| X | X | W | X | X | W | X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ◁ | |||||||

| 1 | X | X | 2 | X | X | 1 | X | X | ||

| X | 2 | 2 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| X | X | X | X | 3 | X | X | ||||

| X | X | X | 1 | X | X | 3 | X | X | X | |

| X | ||||||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| X | ◁ | X | X | X | 1 | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | X | ◁ | 3 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | X | 3 | 1 | 3 | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | 3 | X | X | X | 2 | X | 1 | X | |

| X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | |

| 3 | 1 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 2 | 2 | |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 1 | |||

1990–1999

[edit]| Country | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | ◁ | X | X | X | X | X | X | R | X | |||||||

| X | X | X | ◁ | R | X | X | R | X | X | |||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | R | X | ||||||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| X | X | X | X | R | X | ‡ | X | R | X | |||||||

| ‡ | X | R | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| ◁ | X | ◁ | X | X | R | ◁ | R | X | R | |||||||

| 2 | 2 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| X | X | X | X | 3 | ◁ | ‡ | X | X | 3 | |||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | R | |||||||

| ‡ | X | X | ‡ | X | X | |||||||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | R | 2 | |||||||

| 2 | X | 1 | 1 | 1 | X | 1 | 2 | X | X | |||||||

| X | 3 | X | X | R | X | ‡ | 1 | X | ||||||||

| 1 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| W | ||||||||||||||||

| ◁ | R | R | X | |||||||||||||

| X | X | X | X | R | R | |||||||||||

| ‡ | R | X | R | |||||||||||||

| X | 3 | X | X | X | X | X | 3 | X | ||||||||

| X | X | X | X | R | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| ◁ | X | X | X | X | 1 | 2 | ◁ | X | X | |||||||

| 2 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | |||||||

| ‡ | X | R | ‡ | R | X | R | ||||||||||

| X | X | ‡ | X | R | ||||||||||||

| ‡ | X | R | X | R | X | R | ||||||||||

| X | R | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | 2 | X | X | X | ◁ | |||||||

| X | 1 | X | X | X | 3 | 3 | X | X | 1 | |||||||

| X | X | X | 3 | X | R | X | X | ◁ | R | |||||||

| X | X | X | X | R | X | X | 3 | X | X | |||||||

| X | X | 2 | 2 | X | X | X | 1 | 2 | X | |||||||

| X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

2000–2009

[edit]| Country | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | X | † | † | X | X | |||||

| † | † | † | † | † | † | |||||

| X | X | X | X | |||||||

| X | R | X | X | X | † | † | ||||

| X | 3 | |||||||||

| † | † | † | X | † | † | |||||

| ◁ | R | X | 2 | X | † | † | † | † | † | |

| R | X | X | X | X | X | 3 | X | X | X | |

| † | † | X | † | † | ||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | † | X | X | |

| X | R | X | X | X | X | † | † | † | † | |

| † | † | † | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | ◁ | R | † | X | X | † | X | X | |

| X | 1 | 3 | X | † | † | † | † | † | X | |

| X | R | X | R | † | † | 1 | X | X | ◁ | |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | W | ||||||||

| X | X | X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | X | X | |

| 3 | X | X | 3 | 1 | X | X | 3 | X | ||

| X | X | † | † | |||||||

| X | ◁ | R | X | X | † | † | † | X | 2 | |

| X | X | R | X | X | † | X | ◁ | † | † | |

| X | X | X | X | † | X | X | † | X | X | |

| 3 | X | 1 | X | † | X | X | X | X | † | |

| W | ||||||||||

| R | X | X | R | † | † | X | X | † | X | |

| X | R | X | R | X | X | X | X | † | † | |

| X | X | 2 | X | X | 2 | ◁ | † | † | X | |

| X | X | X | † | X | ||||||

| † | † | † | ||||||||

| † | † | † | ||||||||

| X | X | R | X | X | † | † | † | † | † | |

| X | ◁ | R | X | ◁ | X | X | † | X | 1 | |

| R | X | R | X | X | † | † | † | X | † | |

| R | X | X | † | † | † | † | X | X | ||

| X | R | X | X | X | 3 | X | X | X | X | |

| 2 | X | X | 3 | X | X | 2 | 3 | 1 | X | |

| † | ||||||||||

| 1 | X | † | ||||||||

| 2 | X | W[ae] | ||||||||

| † | ||||||||||

| R | X | X | X | † | † | † | X | † | † | |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| X | R | X | R | † | X | X | † | † | † | |

| X | X | X | 1 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| X | 1 | X | X | 2 | 2 | X | ||||

| X | X | 3 | ◁ | X | X | X | X | ◁ | X | |

2010–2019

[edit]| Country | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | † | X | † | † | X | † | † | X | X | |

| X | † | W | X | X | X | X | X | † | † | |

| X | 2 | X | X | X | ||||||

| X | † | † | 1 | X | X | X | 3 | † | ||

| X | 1 | X | 2 | X | X | X | X | † | X | |

| X | † | † | X | X | † | † | X | † | X | |

| X | † | † | X | † | X | X | X | † | † | |

| X | X | X | † | |||||||

| † | † | † | † | X | 2 | X | ||||

| † | † | † | † | X | X | † | † | |||

| X | † | X | † | X | X | X | 2 | X | ||

| † | X | † | X | X | ||||||

| X | X | X | 1 | X | † | † | X | X | X | |

| † | X | X | X | † | X | † | † | X | X | |

| † | X | † | X | X | † | † | † | X | † | |

| X | X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | X | X | X | |

| X | X | † | X | † | X | X | † | † | † | |

| 1 | X | X | X | X | ◁ | ◁ | X | X | X | |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | † | X | † | X | |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | † | ||

| X | X | X | X | X | † | † | † | † | X | |

| X | X | X | ◁ | † | † | † | † | X | † | |

| X | † | † | † | † | X | X | X | 1 | X | |

| 2 | X | X | X | 3 | X | X | X | 2 | ||

| † | † | † | † | † | X | X | † | † | † | |

| † | X | X | X | † | X | X | † | X | † | |

| † | † | X | X | X | † | X | † | † | X | |

| X | X | X | X | † | † | † | 3 | X | † | |

| † | † | X | X | † | † | † | † | |||

| † | † | † | X | 2 | † | X | X | X | 1 | |

| † | † | X | † | † | † | † | † | † | X | |

| X | † | ◁ | X | X | X | † | X | X | X | |

| † | † | X | X | X | X | † | † | |||

| X | † | † | † | † | 1 | ◁ | † | |||

| 3 | X | X | X | X | X | D | X | † | † | |

| X | X | 2 | X | X | 2 | 3 | W | † | 3 | |

| † | † | † | X | † | † | † | † | X | ||

| X | X | 3 | † | X | X | † | X | X | ||

| † | † | † | ||||||||

| † | X | † | † | X | X | † | † | X | X | |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ◁ | X | X | |

| † | 3 | 1 | X | 3 | 1 | X | X | X | X | |

| † | ◁ | † | † | X | † | † | † | † | X | |

| 2 | † | X | ||||||||

| X | X | X | 3 | X | 1 | X | X | W | ||

| ◁ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ◁ | |

2020–2024

[edit]| Country | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | X | † |

X | †

| |

| C | W | X | X | X | |

| C | † |

X | X | †

| |

| C | † |

† |

X | X | |

| C | X | X | † |

†

| |

| C | D | ||||

| C | X | X | X | †

| |

| C | X | † |

|||

| C | † |

† |

X | 2 | |

| C | X | † |

X | X | |

| C | † |

X | X | †

| |

| C | † |

† |

† |

†

| |

| C | † |

X | X | X | |

| C | X | X | 2 | X | |

| C | 2 | X | X | X | |

| C | † |

† |

† |

X | |

| C | X | ◁ | ◁ | X | |

| C | X | X | † |

X | |

| C | X | X | † |

†

| |

| C | † |

† |

† |

X | |

| C | X | † |

3 | X | |

| C | 1 | X | X | X | |

| C | † |

† |

† |

X | |

| C | X | X | X | X | |

| X | |||||

| C | X | † |

† |

†

| |

| C | X | X | X | †

| |

† |

|||||

| C | X | X | † |

Ð[ag] | |

| C | † |

† |

|||

| C | X | X | X | ◁ | |

| C | † |

X | X | †

| |

| C | X | X | X | X | |

| C | † |

X | † |

||

| C | X | D | |||

| C | X | † |

† |

†

| |

| C | X | X | X | X | |

| C | † |

† |

X | X | |

| C | X | 3 | X | X | |

| C | X | X | 1 | X | |

| C | 3 | X | X | 1 | |

| C | X | 1 | X | 3 | |

| C | ◁ | 2 | X | X | |

Other countries and territories

[edit]A number of broadcasters in non-participating countries and territories have in the past indicated an interest in participating in the Eurovision Song Contest. For broadcasters to participate, they must be a member of the EBU and register their intention to compete before the deadline specified in the rules of that year's event. Each participating broadcaster pays a fee towards the organisation of the contest. Should a country withdraw from the contest after the deadline, they will still need to pay these fees, and may also incur a fine or temporary ban.[28]

China

[edit]China aired the Eurovision Song Contest 2015 and then Chinese provincial television channel Hunan Television had confirmed its interest in participating in the Eurovision Song Contest 2016. The EBU had responded saying "we are open and are always looking for new elements in each Eurovision Song Contest".[29] However, on 3 June 2015, the EBU denied that China would participate as a guest or full participant in 2016.[30]

During the Chinese broadcast of the 2018 contest's first semi-final on Mango TV, both Albania and Ireland were edited out of the show, along with their snippets in the recap of all nineteen entries.[31] Albania was skipped due to a ban that took effect in January 2018 prohibiting showing on television performers with tattoos[32] while Ireland was censored due to its representation of a homosexual couple on-stage.[33] In addition, the LGBT flag and tattoos on other performers were also blurred out from the broadcast.[34] As a result, the EBU terminated its partnership with Mango TV, citing that censorship "is not in line with the EBU's values of universality and inclusivity and its proud tradition of celebrating diversity through music," which led to a ban on televising the second semi-final and the final in the country.[35] A spokesperson for the broadcaster's parent company Hunan TV said they "weren't aware" of the edits made to the programme.[36]

Faroe Islands

[edit]Since 2010, the Faroese national broadcaster Kringvarp Føroya (KVF) has been attempting to gain EBU membership and thus participate independently in the Eurovision Song Contest. However, KVF has so far been denied EBU membership due to the islands being a constituent part of the Danish Realm.[37]

In late 2018, KVF showed renewed interest in joining the EBU and participating in the contest. According to the broadcaster, it was not excluded by the rule that only independent nations can join, and as a result, the Faroese broadcaster started internal discussions on applying for EBU membership and participating in the contest, and additionally organising a national final similar to Dansk Melodi Grand Prix.[38]

The first Faroese artist to compete in the contest was Reiley, who represented Denmark in 2023.[39] Contextually to his participation, KVF, backed by Minister of Social Affairs and Culture Sirið Stenberg, resumed its attempts to gain full EBU membership.[40] In May 2023, KVF announced that it would apply for EBU membership before the summer, with the initial aim of obtaining the status of an associate member.[41] In mid-February 2024, ahead of Faroese singer Janus Wiberg's participation in Dansk Melodi Grand Prix 2024, KVF stated that a five-year plan was being deployed in order to gain EBU membership.[42][43]

Gibraltar

[edit]Since 2006, Gibraltarian broadcaster Gibraltar Broadcasting Corporation (GBC) has been attempting to gain EBU membership and thus participate independently in the Eurovision Song Contest. However, GBC cannot obtain EBU membership due to the British Overseas Territory not being independent from the United Kingdom.[44] The final of the contest was broadcast in Gibraltar between 2006 and 2008.[44][45]

Kazakhstan

[edit]Kazakhstan has never participated in the Eurovision Song Contest. K-1 is negotiating to join the European Broadcasting Union. It has been hoping for pending or approved EBU membership since 2008. If this happens, they may be eligible to compete in the Eurovision Song Contest.[46] Nevertheless, they have broadcast the Eurovision Song Contests from 2010 onwards. However, according to the EBU, no Kazakh broadcaster has ever formally applied to join the EBU.[47]

On 18 December 2015, it was announced that Khabar Agency, a major media outlet in Kazakhstan, had been accepted into the EBU as an associate member,[48] but were still not eligible to take part in the contest under the current rules.[49] Only countries which are part of the European Broadcasting Area are eligible to participate, with Australia being the only exception after its broadcaster being an associate member for over thirty years.

On 22 December 2017, Channel 31 announced that they planned to debut in the 2019 contest, due to their new EBU membership.[50]

Kazakhstan made its debut at the Junior Eurovision Song Contest 2018 alongside Wales, placing sixth.[51] On 30 July 2018, the EBU stated that the decision to invite Kazakhstan was made solely by the Junior Eurovision Steering Group, and there were no current plans to invite associate members other than Australia.[52]

On 22 November 2018, the then executive supervisor of the contest, Jon Ola Sand, stated in a press conference that "we need to discuss if we can invite our associate member Kazakhstan to take part in the adult ESC in the future, but this is part of a broader discussion in the EBU and I hope we can get back to you on this issue later."[53] However, Sand later clarified that Kazakhstan would not have an entry in the 2019 edition.[54]

Khabar Agency has not broadcast the contest since 2022 due to low viewership and the time zone difference.[55]

Kosovo

[edit]Kosovo has never participated in the Eurovision Song Contest on its own, but the contest has had a long history within the country, which has broadcast it since 1961. After the start of Kosovo's UN administration, the Kosovan public broadcaster RTK was independently licensed by the EBU to broadcast all three shows. Despite not having participated in the song contest, Kosovo did participate in the Eurovision Young Dancers 2011 and the Turkvision Song Contest.

As Kosovo is not a member of the United Nations and RTK not a member of the International Telecommunication Union, RTK cannot apply to become a full member of the EBU.[56]

Jugovizija was the national pre-selection of Yugoslavia organised by the Yugoslav broadcaster Yugoslav Radio Television (JRT) since 1961 and it featured entries submitted by the subnational public broadcasting centres based in the capitals of each of the constituent republics and autonomous provinces. Each broadcasting centre had its own regional jury. SAP Kosovo was represented by RTV Priština, but their entry never won. Jugovizija 1986 was organised by RTV Priština. Before the Kosovo declaration of independence in 2008, Viktorija, a singer from Vučitrn, represented Yugoslavia as part of Aska in 1982; and Nevena Božović, who is from Mitrovica, represented Serbia in the Junior Eurovision Song Contest 2007. After the breakup of Yugoslavia, numerous Kosovo Albanian singers have participated at the Festivali i Këngës, the Albanian national selection for Eurovision organised by RTSH. The most notable participants to date are Rona Nishliu, Lindita, and Albina Kelmendi and her family, who represented Albania in 2012, 2017 and 2023, respectively. Numerous Kosovo Serb singers have participated in Serbian national selections organised by RTS. Nevena Božović also represented Serbia as a member of Moje 3 in 2013 and as a solo artist in 2019.

After Kosovo's declaration of independence from Serbia in 2008, RTK applied for EBU membership, and wished to enter Kosovo into the 2009 contest.[57][58] There is a signed co-operation agreement between the EBU and RTK; and the EBU supports the membership of RTK. Since 2013, RTK has had observer status within the EBU, and did participate in the Eurovision Young Dancers 2011.[59][60] According to the Kosovan newspaper Koha Ditore, a possible entry would have been selected via a national final called Akordet e Kosovës, a former pop show that had been taken off the air some years ago.[61][62][63]

In February 2023, RTK announced that it was developing a format bearing the same title of Festivali i Këngës, with the long-term aim of using it as the Kosovan national final for the contest, similarly to its Albanian counterpart.[64][65] Later that year, the broadcaster confirmed that it would continue its efforts to obtain EBU membership,[66] and opened a submission period for the first edition of the event, which was held between 26 and 28 October 2023.[67] Shortly before the launch, the festival's director, Adi Krasta, reported that people at EBU had expressed their enthusiasm about the event,[68] with director-general of the EBU Noel Curran making a remote appearance during the first night of the festival to express his congratulations.[69] Following the first edition, the CEO of RTK, Besnik Boletini, reaffirmed the country's continued efforts in order to be included in the contest as early as 2025.[70]

RTK was first present as an observer at the EBU general assembly in December 2023.[71] A vote on the draft of Kosovo's application to the Council of Europe took place on 16 April 2024, which was approved by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe was set to decide on Kosovo's membership in May 2024,[72] but was removed from the agenda following Kosovo's rejection of French and German prerequisites for membership.[73] Membership in the council would enable Kosovo to join the EBU as a full member and compete in the contest by 2025.[74][75] In May 2024, RTK announced that it would submit an application for EBU membership "soon",[76] and by mid-June, it submitted a formal request of invitation to the contest, despite still lacking full EBU membership;[77] this was rejected in July.[78]

Liechtenstein

[edit]Liechtenstein has never participated in the Eurovision Song Contest: the principality has been prevented from competing due to the lack of a national broadcaster which is a member of the EBU.[79] Attempts were made in the 1970s by the Liechtenstein government for the nation to participate, with a two-song national final held in November 1975 choosing "My Little Cowboy" sung by Biggi Bachmann and written by Mike Tuttlies and Horst Hornung as the winner over "Tu étais mon clown" by Anne Frommelt.[80] The song was supposed to be the country's debut entry for the 1976 contest; however due to a misunderstanding by Liechtenstein's government of the rules of participation, the entry was rejected due to a lack of national broadcaster with which to participate.[81]

On 15 August 2008, 1 FL TV, licensed by the country's government, became the first broadcaster based in Liechtenstein. This would allow the country to begin competing at the Eurovision Song Contest for the first time, should they decide to join the EBU, a pre-requisite for entering the contest.[82][83] Shortly after its foundation however, the broadcaster announced that they were not interested in joining the EBU or Eurovision at that time because they had no budget for membership.[84]

In July 2009, the broadcaster officially announced its intention to apply to join the EBU by the end of July, with the intention to take part in the Eurovision Song Contest 2010 in Oslo.[85] Peter Kölbel, managing director of 1FLTV, officially confirmed the broadcaster's interest, revealing that they had plans to develop a national final similar to Deutschland sucht den Superstar, the German version of the Idol series.[86] In November 2009, 1FLTV decided to postpone EBU and Eurovision plans, for financial reasons, and began to search for other options for funding EBU membership in the future.[87][88]

1FLTV submitted its application for EBU membership on 29 July 2010. If accepted, 1FLTV would have gained full EBU membership and would have been able to send an entry to the Eurovision Song Contest 2011.[89] However, Liechtenstein did not appear on the official list of participants for Eurovision 2011. In late 2012, Peter Kölbel, director of 1FLTV, stated that Liechtenstein would not be able to take part until 2013 at the earliest. The broadcaster had been trying to get government subsidies since 2010 to enable participation, and participation was likely if the Government approved funding by April 2012.

On 10 September 2013, 1FLTV confirmed that Liechtenstein would not be participating at the Eurovision Song Contest 2014 in Copenhagen, Denmark.[90] The broadcaster has no plans to join the EBU at the moment. This was confirmed again on 28 July 2014 in the run-up to the Eurovision Song Contest 2015 in Austria. 1FLTV did however state their interest in participating in the Eurovision Song Contest, but said that they would have to evaluate the costs of EBU membership, a necessary prelude to participation.[91] Once again in 2016, the nation did not compete, due to lack of funds to join the EBU.[92] On 21 September 2016, 1FLTV announced that they would not be able to debut to the contest in 2017, but that they would set their eyes on a future participation once they overcome their financial hurdles.[93] Yet again, on 1 September 2017 they also announced they would not debut at the 2018 contest in Lisbon.[94]

On 4 November 2017, the broadcaster stated that it was planning to debut in the Eurovision Song Contest in 2019 and would organise a national selection to select both the singer and the song.[95] However, on 20 July 2018, the EBU stated that 1 FL TV had not applied for membership.[96] The broadcaster later halted its plans to apply for EBU membership when its director, Peter Kölbel, unexpectedly died. It would also need the backing of the Liechtenstein government to be able to carry the cost of becoming an EBU member and paying the participation fee for the contest.

On 9 August 2022, 1 FL TV's managing director Sandra Woldt confirmed that the broadcaster would not be aiming to apply for EBU membership, thereby indefinitely ruling out a debut in the Eurovision Song Contest.[97] The broadcaster's intentions were reiterated the following year.[98] On 15 May 2024, Liechtensteiner Vaterland reported that a different broadcaster, Radio Liechtenstein, was in the process of applying for EBU membership with the aim of participating in the contest.[99][100]

Qatar

[edit]Qatar Radio (QR) first revealed on 12 May 2009 that they were interested in becoming active members of the union, which would allow Qatar to compete in the contest. The nation first became involved in the contest at that year's edition, where the broadcaster sent a delegation to the contest and broadcast a weekly radio show called 12pointsqatar dedicated to Eurovision, which received favourable responses. Qatar Radio said that they hoped to join Eurovision by 2011 and that they would be happy to join all other competitors in the contest, including Israel, if the country received a membership.[2] The broadcaster appeared as an associate member of the EBU in 2009, but was removed sometime later.[101]

Qatar is required to have a TV broadcaster which has at least associate membership of the EBU in order to have a chance to take part, as Qatar Radio is only a radio station and Qatar lies outside the European Broadcasting Area and cannot apply for Council of Europe membership, with Australia being the only exception after being an associate member for over 30 years. The broadcaster would most likely be Qatar Television (QTV), which is also owned by the Qatar General Broadcasting and Television Corporation (QGBTC). If Qatar Radio gets reaccepted, it would be able to air the contest alongside the television broadcast.[2]

Soviet Union

[edit]The Soviet Union never participated in the Eurovision Song Contest prior to its dissolution in 1991, however several of the post-Soviet states which emerged or re-emerged following this process went on to compete in the Eurovision Song Contest. All former republics of the Soviet Union which were geographically situated in Europe (except for Kazakhstan) went on to make their debut appearances in the contest during the 1990s and 2000s: Estonia, Lithuania and Russia in 1994;[102][103][104] Latvia in 2000;[105] Ukraine in 2003;[106] Belarus in 2004;[107] Moldova in 2005;[108] Armenia in 2006;[109] Georgia in 2007;[110] and Azerbaijan in 2008.[111]

Of the ten former Soviet republics to have taken part, five have gone on to win the contest. Estonia became the first to win in 2001, followed by Latvia in 2002, Ukraine in 2004, Russia in 2008, and Azerbaijan in 2011.[102][112] Ukraine is the only former Soviet country to have won the contest more than once, having secured three wins in 2004, 2016 and 2022.[113]

The contest was reportedly first broadcast on television in the Soviet Union in 1965, and for many years the contest was intermittently broadcast on Soviet Central Television who received it via the OIRT's Intervision network.[114][115][116] The contest was also broadcast on Eesti Televisioon within the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic from 1986.[116]

| Year | Channel | Commentator(s) | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soviet Union-wide | Estonian SSR | |||

| 1986 | Programme One | ETV | Unknown | [117][118] |

| 1987 | [119][120] | |||

| 1988 | [121][122] | |||

| 1989 | [123][124] | |||

| 1990 | [125][126] | |||

| 1991 | [127][128] | |||

Broadcast in non-participating countries

[edit]The contest has been broadcast in several countries that do not compete, such as the United States, Canada, New Zealand, and China. Since 2000, it has been broadcast online via the Eurovision website.[129] It was also broadcast in several countries East of the Iron Curtain that have since dissolved, such as Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and the Soviet Union.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- List of countries in the Eurovision Young Dancers

- List of countries in the Eurovision Young Musicians

- List of countries in the Junior Eurovision Song Contest

Notes

[edit]- ^ Namely France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom (the initial "Big Four"); with Italy joining them when it returned to the contest in 2011.

- ^ Flemish broadcaster and Walloon broadcaster alternate participation in the contest representing Belgium, with both broadcasters sharing the broadcasting rights.

- ^ Since 1978; previously represented by Institut national belge de radiodiffusion (INR; 1956–1960) and Radio-Télévision Belge (RTB; 1961–1977).

- ^ Since 1998; previously represented by Nationaal Instituut voor de Radio-omroep (NIR; 1956–1960), Belgische Radio- en Televisieomroep (BRT; 1961–1990), and Belgische Radio- en Televisieomroep Nederlandstalige Uitzendingen (BRTN; 1991–1997).

- ^ Since 2005; previously represented by Radio Television of Bosnia and Herzegovina (RTVBiH; 1993–2000) and the Public Broadcasting Service of Bosnia and Herzegovina (PBSBiH; 2001–2004).

- ^ a b Participated as Czech Republic until 2022.

- ^ Since 2008; previously represented by Eesti Televisioon (ETV) between 1993 and 2007.

- ^ Since 2001; previously represented by Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF; 1956–1964), Office de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française (ORTF; 1965–1974), Télévision Française 1 (TF1; 1975–1981), Antenne 2 (1983–1992), and France Télévision (1993–2000).

- ^ a b c d e Member of the "Big Five".

- ^ Responsibility for organising ARD's entry rests with one of its member broadcasters, and has changed hands over the years. Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR) is currently representing Germany since 1996.[13] See Germany in the Eurovision Song Contest § Organisation for full history of German participant broadcasters.

- ^ Represented by the National Radio Television Foundation (EIRT) in 1974 and the New Hellenic Radio, Internet and Television (NERIT) in 2014 and 2015.

- ^ Since 2011; previous represented by Magyar Televízió between 1993 and 2010

- ^ Since 2010; previously represented by Radio Éireann (RÉ) in 1965 and 1966, and Radio Telefís Éireann (RTÉ) between 1967 and 2009.

- ^ Since 2018; previously represented by the Israel Broadcasting Authority (IBA) between 1973 and 2017.

- ^ Since 2024; previously represented by the Compagnie Luxembourgeoise de Télédiffusion (CLT) between 1956 and 1993.

- ^ Since 1991; previously represented by the Maltese Broadcasting Authority (MBA) between 1971 and 1975.

- ^ Between 1959 and 2006. TVMonaco (TVM) is the current EBU member in the country since 2024, thus eligible to participate in the contest.

- ^ Represented by Radiodiffusion-Télévision Marocaine (RTM) in 1980. Société Nationale de Radiodiffusion et de Télévision (SNRT) is the current EBU member in the country, thus eligible to participate in the contest.

- ^ Since 2014; previously represented by Nederlandse Televisie Stichting (NTS; 1956–1969), Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (NOS; 1970–2009), and Televisie Radio Omroep Stichting (TROS; 2010–2013).

- ^ a b The 2024 entry qualified for the final, but was removed from the competition following a backstage incident during the semi-final. The Netherlands retained the right to vote in the final.

- ^ a b Participated as F.Y.R. Macedonia until 2019.

- ^ Since 2004; previously represented by Radiotelevisão Portuguesa (RTP; 1964–2003).

- ^ RTR and C1R alternated responsibilities for the contest.

- ^ In 2011 and 2012; previously represented by Slovenská televízia (STV) between 1994 and 2010. Slovenská televízia a rozhlas (STVR) is the current EBU member in the country since 2024, thus eligible to participate in the contest.

- ^ Since 2007; previously represented by Televisión Española (TVE) between 1961 and 2006.

- ^ Since 1980; previously represented by Sveriges Radio (SR) between 1958 and 1979.

- ^ Since 2017; previously represented by the National Television Company of Ukraine (NTU) between 2003 and 2016.

- ^ The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia competed as "Yugoslavia" in 1992.

- ^ Succeeded by Česká televize (ČT) of the Czech Republic and Slovenská televízia (STV) of Slovakia.

- ^ Each country was represented by two songs in the 1956 contest; Switzerland's win in this contest was with one of their two songs.

- ^ Serbia and Montenegro kept their voting rights after they withdrew.

- ^ The 2020 contest was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- ^ The Netherlands kept their voting rights in the final after they were disqualified.

- ^ Broadcasting rights were revoked after the first semi final due to their censorship of the Irish performance, in which 2 male dancers were representing a same sex couple.

References

[edit]- ^ "Admission". EBU. European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ a b c Repo, Juha (12 May 2009). "Gulf nation wants to join Eurovision". ESCToday. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ ESCtoday.com. Eurovision Song Contest 1993 Archived 12 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2 February 2008.

- ^ O'Connor, John Kennedy (2005). The Eurovision Song Contest 50 Years The Official History. London: Carlton Books Limited. ISBN 1-84442-586-X.

- ^ ESCtoday.com. Eurovision Song Contest 1996 Archived 23 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2 February 2008.

- ^ Eurovision.tv. Eurovision Song Contest 1997 Archived 20 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2 February 2008.

- ^ BBC News (12 May 2004). Eurovision finalists chosen Archived 4 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2 February 2008.

- ^ a b European Broadcasting Union (1 October 2007). Two semi-finals Eurovision Song Contest 2008 Archived 1 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2 February 2008.

- ^ Ian Taylor (14 May 2007). From pariah state to kitsch victory: how a Balkan ballad showed Europe a new Serbia Archived 7 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Retrieved on 9 February 2008.

- ^ Farren, Niel (30 June 2024). "Belarus: BTRC Indefinitely Suspended From EBU". Eurovoix. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Європейська мовна спілка призупинила членство російських ЗМІ" [The European Broadcasting Union has suspended membership of the Russian media]. suspilne.media (Press release) (in Ukrainian). UA:PBC. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ "History by country". Eurovision.tv. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "Alle deutschen ESC-Acts und ihre Titel". www.eurovision.de (in German). ARD. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ a b Carlson, Christopher (7 June 2019). "Where are they?". Eurovisionworld. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Werber, Cassie (23 May 2015). "The Vatican was asked to participate in the Eurovision Song Contest. It declined, again". Quartz. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ X Tra (19 February 2005). "Aline Lahoud to sing Quand tout s'enfuit". ESCToday. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ Christian, Nicholas (20 March 2005). "Nul points as Lebanon quits contest". Scotland on Sunday. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ "EBU – Eurovision Choir". www.ebu.ch. 27 February 2017. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ a b Kuipers, Michael (20 June 2007). "Tunisia will not participate "in the forseeable future"". ESCToday. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ a b Cobb, Ryan (22 May 2018). "Israeli Minister "to invite" Arabic nations, including Tunisia, to take part in Eurovision 2019". ESCXtra. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ "Chwilio am Seren". junioreurovision.cymru. S4C. 9 May 2018. Archived from the original on 26 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (3 April 2017). "Wales confirms participation in Eurovision Choir of the Year 2017". Eurovoix. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (3 May 2024). "Wales: Campaign Commences for Eurovision Participation". Eurovoix. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Eurovision.tv. Eurovision Song Contest 1970 Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 9 February 2008.

- ^ ESCtoday.com (27 November 2002). No new countries at next Eurovision Song Contest Archived 18 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 11 February 2008.

- ^ ESCtoday.com (27 November 2002). EBU released list of participants for 2003 Archived 25 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 11 February 2008.

- ^ Eurovision.tv (27 October 2006). Georgia set on 2007 Archived 18 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 11 February 2008.

- ^ BBC News (20 March 2006). Row prompts Eurovision withdrawal Archived 9 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 14 February 2008.

- ^ Lee Adams, William (22 May 2015). "China: Exclusive: China'S Hunan TV exploring Eurovision participation". wiwibloggs. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Muldoon, Padraig (3 June 2015). "Eurovision 2016: EBU denies Kosovo and China rumours". Wiwibloggs. wiwibloggs.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Park, Andrea (10 May 2018). "China censors Ireland's gay-themed Eurovision performance". CBS News. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ "China Just Banned Hip-Hop Culture and Tattoos From Television". Time.com. 22 January 2018. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Avelino, Gerry (9 May 2018). "China: Ireland and Albania removed from semi-final 1 broadcast". Eurovoix. Archived from the original on 13 October 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "China channel barred from airing Eurovision". BBC News. 11 May 2018. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Statement 10 May: EBU terminates this year's partnership with Mango TV". eurovision.tv. 10 May 2018. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ Washington, Jessica (11 May 2018). "China banned from broadcasting Eurovision after censoring same-sex dance". SBS News. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (10 June 2015). "Faroe Islands want to participate in the Eurovision Song Contest". Eurovoix. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "The Faroe Islands wants EBU membership and right to participate at Eurovision". 30 December 2018. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Reiley: 'The people of the Faroe Islands are so excited to have one of their own representing their nation.'". ESCBubble. 26 April 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (12 May 2023). "Faroe Islands: Hopeful of EBU Membership in the Future". Eurovoix. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ "Faroes set sights on Eurovision membership". Kringvarp Føroya. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (20 February 2024). "Faroe Islands: KVF Continues to Progress With Plans for EBU Membership". Eurovoix. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Jensen, Frants (16 February 2024). "Fíggjarstøðan í KVF ein forðing fyri EBU-limaskapi" (in Faroese). Kringvarp Føroya. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ a b Granger, Anthony (9 May 2019). "Gibraltar: GBC Explains Eurovision Broadcasts from 2006 to 2008". Eurovoix. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (25 March 2015). "Gibraltar: No Plans To Broadcast Eurovision". eurovoix.com. Eurovoix. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ "Kazajistán negocia su incorporación a la UER". Eurovision Spain (in Spanish). 3 January 2013. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "EBU on Twitter: "@Karl_Downey No broadcaster from Kazakhstan has formally applied to join the EBU"". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "EBU on Twitter: "We can confirm that @KhabarTV was confirmed as an EBU Associate at our recent General Assembly"". Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ "EBU on Twitter: "Under current rules @KhabarTV is not eligible for @Eurovision participation"". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ "Kazakhstan's Channel 31 claims: "We will participate in Eurovision 2019!"". ESCXTRA. 22 December 2017. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ "These are the 19 (!) countries taking part in Junior Eurovision 2018". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. 25 July 2018. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Cobb, Ryan (30 July 2018). "Official EBU statement: "No plans" to invite Kazakhstan to Eurovision 2019". ESCXTRA. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ Cobb, Ryan (22 November 2018). "Jon Ola Sand: Kazakhstan participation in adult Eurovision "needs to be discussed"". ESCXTRA. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Cobb, Ryan (23 November 2018). "No entry in Eurovision 2019 for Kazakhstan, clarifies Jon Ola Sand". ESCXTRA. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ ""Хабар" не покажет финал Евровидения в этом году из-за низких рейтингов шоу". informburo.kz (in Russian). 13 May 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Juhász, Ervin (28 June 2019). "No changes in the EBU statutes, thus Kosovo can't apply for full membership". ESCBubble. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Kosovo: RTK wants to enter Eurovision in 2009". oikotimes.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ^ "NDR on the Kosovo potential participation in Eurovision" Archived 29 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine oikotimes.com 22 May 2008 Link accessed 27 May 2008

- ^ Albavision (7 April 2011). "Kosovo new steps in ebu agreement". albavision.tk. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ "Participant Profile – Kosovo". European Broadcasting Union. 2011. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ Eurosong (19 April 2008). "Kosovo wil snel deelnemen aan het Songfestival" (in Dutch). eurosong.be. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ setimes (8 April 2010). "EBU membership key to Kosovo's Eurovision future". Setimes.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ Eurovisionary (2 June 2011). "Kosovo a possible candidate for Eurovision?". eurovisionary.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ Kurris, Denis (12 March 2023). "Eurovision: Kosovo is creating a Eurovision national selection". ESCplus. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ "Nga ky vit, nis Festivali i Këngës në RTK". Demokracia (in Albanian). 9 February 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (11 May 2023). "Kosovo: RTK Continuing to Push for EBU Membership". Eurovoix. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ "Festivali i Këngës". RTKLive (in Albanian). RTK. 2 June 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ Heap, Steven (19 October 2023). "Kosovo: EBU Reportedly Positive of Festivali i Këngës ne RTK". Eurovoix. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ RTK [@festivalirtk] (26 October 2023). "Drejtori i Përgjithshëm i EBU-së , Noel Curran, përgëzon RTK-në për organizimin e Festivalit të Këngës" [The Director-General of the EBU, Noel Curran, congratulates RTK for organising Festivali i Këngës] (in Albanian). Retrieved 26 October 2023 – via Instagram.

- ^ Pasoma, Medina (29 October 2023). "'Post Festival' përmbledh Festivalin e Këngës, ia hap dyert dokumentarit" ["Post Festival" summarises Festivali i Këngës, opens the doors to the documentary]. RTKLive (in Albanian). RTK. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Ntinos, Fotios (8 December 2023). "Κosovo: RTK present at the EBU's General Assembly!". Eurovisionfun. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "PACE adopts opinion on Kosovo's application to CoE". N1. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ "Kosovo PM Rejects West's Terms for CoE Membership". BalkanInsight. 8 May 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ Selimi, Petrit (14 March 2024). "Kosovo's Taken Crucial Step to Join Council of Europe". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Baccini, Federico (28 March 2024). "Council of Europe committee recommendation on Kosovo reignites tensions with Serbia". Eunews. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Stephenson, James (9 May 2024). "Kosovo: RTK Will Apply for Eurovision Participation 'Soon'". Eurovoix. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ Stephenson, James (13 June 2024). "Kosovo: RTK Requests Invitation to Eurovision 2025". Eurovoix. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ Limani, A. (9 August 2024). "Kërkesa e RTK-së për pjesëmarrje në Eurovision merr përgjigje negative" [RTK's request for participation in Eurovision receives a negative response]. Zëri (in Albanian). Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ "The Eurovision Song Contest 1956 – present". BBC. 26 April 2007. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Stober, Marcel (29 August 2020). "Biggi Bachmann: Wie Liechtenstein fast am ESC teilnahm". Eurovision.de. ARD. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "TV-Grand Prix ohne Biggi Bachmann" [TV Grand Prix without Biggi Bachmann]. Liechtensteiner Volksblatt (in German). Schaan, Liechtenstein. 31 January 1976. p. 6. Retrieved 29 September 2024 – via Liechtenstein State Library.

- ^ Kuipers, Michael (24 August 2008). "Liechtenstein gets a TV station". ESCToday. Archived from the original on 25 August 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Backfish, Emma (31 August 2008). "Liechtenstein gets national TV station". Oikotimes. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "1FL TV from Lichtenstein not entering the EBU & Eurovision". Oikotimes. 6 October 2008. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Harley, Lee (21 July 2009). "Liechtenstein: Set to debut in Eurovision 2010?". Oikotimes. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "News Eurovision Russia 2009". ESCKaz. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Hondal, Victor (4 November 2009). "Liechtenstein rules out Eurovision participation". ESCToday. Archived from the original on 6 November 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Coroneri, Alenka (4 November 2009). "Liechtenstein decides to postpone Eurovision plans". Oikotimes. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ "Liechtenstein: 1FL expects "good chances" for Eurovision debut". ESCToday. 30 July 2010. Archived from the original on 2 August 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ^ "Liechtenstein: No debut in Eurovision 2014!". ESCToday. 10 September 2013. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ Jiandani, Sergio (28 July 2014). "Liechtentestein: 1 FL TV will not debut in Eurovision 2015". esctoday.com. ESCToday. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Jiandani, Sanjay (16 September 2015). "Liechtenstein: 1 FL TV will not debut in Stockholm". esctoday.com. ESCToday. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ Jiandani, Sanjay (21 September 2016). "Liechtenstein: 1 FL TV will not debut in Kyiv; sets its eyes on a future ESC participation". ESCToday. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Jiandani, Sanjay (1 September 2017). "Liechtenstein: 1 FL TV will not debut in Eurovision 2018". esctoday.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Liechtenstein: 1FLTV plans Eurovision debut in 2019". eurovoix.com. 4 November 2017. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "'Liechtenstein have not applied' confirms EBU". EscXtra. 20 July 2018. Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (9 August 2022). "Liechtenstein: 1 FL TV Rules Out Applying For EBU Membership". Eurovoix. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Jiandani, Sanjay (10 August 2023). "Liechtenstein: 1 FL TV will not debut at Eurovision 2024". ESCToday. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (2 June 2024). "Liechtenstein: Radio Liechtenstein Applying for European Broadcasting Union Membership". Eurovoix. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Kaufmann, Gary (15 May 2024). "Radio Liechtenstein prüft ESC-Teilnahme". Liechtensteiner Vaterland (in German). Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Repo, Juha (6 June 2012). "New EBU members? Not very likely". ESCToday. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Estonia". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Lithuania". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Russia". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Latvia". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Belarus". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Moldova". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Armenia". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Georgia". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Azerbaijan". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Eurovision Archives". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Eurovision 2022: Ukraine wins, while the UK's Sam Ryder comes second". BBC News. 14 May 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ Roxburgh, Gordon (2012). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Volume One: The 1950s and 1960s. Prestatyn: Telos Publishing. pp. 369–381. ISBN 978-1-84583-065-6.

- ^ "Naples 1965". Eurovision Song Contest. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ a b See individual references embedded within the "Commentators and spokespersons" table.

- ^ "Телевидение: Программа на неделю" [Television: Weekly programmes] (PDF). Pravda (in Russian). 24 May 1986. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ "R. 30. V" [F. 30 May]. Televisioon : TV (in Estonian). No. 22. Tallinn, Estonian SSR, Soviet Union. 26 May – 1 June 1986. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 21 June 2024 – via DIGAR.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Телевидение, программа на неделю" [Television, weekly program] (PDF). Pravda (in Russian). 29 May 1987. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ "N. 4. VI" [T. 4. June]. Televisioon : TV (in Estonian). No. 23. Tallinn, Estonian SSR, Soviet Union. 1–7 June 1987. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 21 June 2024 – via DIGAR.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Телевидение, программа на неделю" [Television, weekly programme] (PDF). Pravda (in Russian). Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union. 28 May 1988. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ "L. 4. V" [S. 28. May]. Televisioon : TV (in Estonian). No. 22. Tallinn, Estonian SSR, Soviet Union. 23–29 May 1988. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 21 June 2024 – via DIGAR.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Телевидение, программа на неделю" [Television, weekly program] (PDF). Pravda (in Russian). 6 May 1989. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "L. 6. V" [S. 6 May]. Televisioon : TV (in Estonian). No. 18. Tallinn, Estonian SSR, Soviet Union. 1–7 May 1989. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 21 June 2024 – via DIGAR.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Телевидение – Суббота ⬥ 5" [Television – Saturday ⬥ 5] (PDF). Pravda (in Russian). 28 April 1990. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ "L. 5. V" [S. 5 May]. Televisioon : TV (in Estonian). No. 18. Tallinn, Estonian SSR, Soviet Union. 30 April – 6 May 1990. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 21 June 2024 – via DIGAR.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Телевидение – Суббота ⬥ 4" [Television – Saturday ⬥ 4] (PDF). Pravda (in Russian). 27 April 1991. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ "4 V – Laupäev" [4 May – Saturday]. Televisioon : TV (in Estonian). No. 18. Tallinn, Estonian SSR, Soviet Union. 29 April – 5 May 1991. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 21 June 2024 – via DIGAR.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Philip Laven (July 2002). "Webcasting and the Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "Eurovision to Be Shown In U.S. for the First Time". Billboard. 6 March 1971. p. 54. Retrieved 17 May 2024 – via Google Books.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Roxburgh, Gordon (2014). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Two: The 1970s. Prestatyn: Telos Publishing. pp. 25–37. ISBN 978-1-84583-093-9.

- ^ "Festival Eurovision de la Cancion 1970" [Eurovision Song Contest 1970]. Crónica. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 23 March 1970. p. 21. Retrieved 13 July 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "A África também vai ver o Grande Prémio da Eurovisão". Diário de Lisboa (in Portuguese). Mário Soares Foundation. 3 April 1971. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ "Boutique Carnaby ta presenta – Diadomingo 5 Mei pa 5.00 di atardi Eurovisie Festival – Atravez di PJA-10 Voz di Aruba" [Boutique Carnaby presents – Sunday 5 May at 5:00 pm Eurovision Festival – Through PJA-10 Voice of Aruba]. Amigoe di Curaçao (in Dutch and Papiamento). Willemstad, Curaçao. 4 May 1974. p. 4. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Agenda Aruba | Zondag – Telearuba" [Agenda Aruba | Sunday – Telearuba]. Amigoe (in Dutch). Willemstad, Curaçao. 16 July 1977. p. 5. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ a b c d e f "Eurovision Song Contest 1972 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Zapping transmitirá festival de música Eurovision no Brasil com exclusividade" [Zapping will broadcast the Eurovision Song Contest in Brazil on exclusive]. TelaViva (in Brazilian Portuguese). 9 May 2024. Archived from the original on 11 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "La télévision de dimanche soir en un clin d'oeil" [Sunday night television at a glance]. Le Devoir. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 28 May 1988. p. C-7. Retrieved 17 June 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ "La télévision de samedi soir en un clin d'oeil" [Saturday night television at a glance]. Le Devoir. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 6 May 1989. p. C-10. Retrieved 17 June 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Télé–horaire de la semaine du 8 au 14 mai 2000 – TV5 – Samedi" [Television timetable for the week of May 8 to 14, 2000 – TV5 – Saturday]. La Liberté. Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. 5 May 2000. p. 16. Retrieved 17 June 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Votre soirée de télévision" [Your evening of television]. La Presse. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 25 May 2002. p. D2. Retrieved 18 October 2024 – via National Library and Archives of Quebec.

- ^ a b "BBC Online – Eurovision Song Contest – Information". 2 May 1999. Archived from the original on 2 May 1999. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (2 April 2015). "Canada: OUTtv to broadcast Eurovision 2015". Eurovoix. Archived from the original on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (9 February 2019). "Canada: OMNI Television to Broadcast Eurovision 2019". Eurovoix. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Recalling Sweden's first staging of the contest in 1975". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Vía Satélite". Las Últimas Noticias (in Spanish). 19 March 1970. p. 11.

El próximo sábado Rául Matas, director de programas de Canal Nacional, realizará una transmisión excepcional desde Amsterdam, Holanda, por Canal 7 de Televisión. Se trata del Festival de Eurovisión, al que Matas le dedicará todas sus energías mientras dure el evento que se transmitirá vía satélite.

- ^ "Por primera vez en Chile: Canal 13 da el golpe y transmitirá en vivo la final de Eurovisión". TVD al Día (in Spanish). 30 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Zapping transmitirá este fin de semana la final del festival Eurovisión 2024" [Zapping will broadcast the final of the Eurovision 2024 festival this weekend]. TVD al Día (in Spanish). 7 May 2024. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Siim, Jamo (2 October 2013). "Eurovision 2013 reaches China". Eurovision Song Contest. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ^ "Hoy es noche de gala: Festival Eurovision 1969" [Today is gala night: Eurovision Festival 1969]. La Nación (in Spanish). 4 May 1969. pp. 86–87. Retrieved 15 May 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Radio–Televisie – woensdag – Telecuraçao" [Radio–Television – Wednesday – Telecuraçao]. Amigoe di Curaçao (in Dutch). Willemstad, Curaçao. 20 May 1964. p. 2. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Maandagavond om half tien brengt het Bureau voor Cultuur en Opvoeding via TeleCurcao en reportage van het Eurovisie Festival 1973" [Monday evening at half past ten, the Bureau for Culture and Education will report via TeleCurcao from the Eurovision Festival 1973]. Amigoe di Curaçao. Willemstad, Curaçao. 12 May 1973. p. 8. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Agenda Curaçao | Zaterdag – Telecuraçao" [Agenda Curaçao | Saturday – Telecuraçao]. Amigoe (in Dutch). Willemstad, Curaçao. 28 May 1977. p. 2. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Telecuraçao – Zaterdag" [Telecuraçao – Saturday]. Amigoe (in Dutch). Willemstad, Curaçao. 12 April 1979. p. 2. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "(zaterdag) Telecuraçao" [(Saturday) Telecuraçao]. Amigoe (in Dutch). Willemstad, Curaçao. 13 July 1981. p. 2. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Telecuraçao – Zaterdag" [Telecuraçao – Saturday]. Amigoe. Willemstad, Curaçao. 7 July 1984. p. 2. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "TV – Saturday Evening – June 3, 1995". Amigoe (in Dutch). Willemstad, Curaçao. 3 June 1995. p. 15. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest 1981 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ "Kringvarpið vísir Eurovision Song Contest 2023". kvf.fo (in Faroese). Kringvarp Føroya. Archived from the original on 10 May 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "Nuuk TV – Lørdag den 25. juni". Atuagagdliutit (in Danish). Nuuk, Greenland. 23 June 1977. p. 16. Retrieved 8 May 2024 – via Timarit.is.

- ^ "Isiginnaarut / TV" [Movies / TV]. Atuagagdliutit (in Kalaallisut and Danish). Nuuk, Greenland. 21 May 1981. p. 38. Retrieved 30 October 2024 – via Timarit.is.

- ^ a b "Eurovisie Songfestival direct naar 26 landen" [Eurovision Song Contest goes straight to 26 countries]. Leeuwarder Courant (in Dutch). Leeuwarden, Netherlands. 2 April 1976. p. 2. Retrieved 26 August 2024 – via Delpher.