Isle Brevelle

Isle Brevelle | |

|---|---|

Community | |

| |

| Coordinates: 31°38′37″N 093°01′43″W / 31.64361°N 93.02861°W | |

| Country | United States |

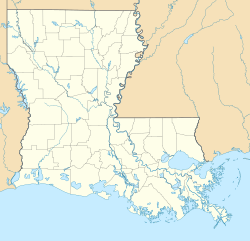

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Natchitoches Parish |

| Named for | Jean Baptiste Brevelle II |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

Isle Brevelle is an ethnically and culturally diverse community, which began as a Native American and Louisiana Creole settlement and is located in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana. For many years this area was known as Côte Joyeuse (English: Joyous Coast). It is considered the birthplace of Creole culture and remains the epicenter of Creole art and literature blending European (predominantly French and Spanish), African, and Native American cultures. It is home to the Cane River Creole National Historical Park and part of the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail.[1]

Location

[edit]Located in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, Isle Brevelle consists of approximately 18,000 acres of land between the Cane River and Bayou Brevelle (near Montrose).[2][3] Two major highways in Isle Brevelle include LA 119 and LA 484.[3]

The island is a narrow strip of land some thirty miles in length with three- to four-mile breadth located south of Natchitoches, Louisiana. It is delineated and split by waterways to include the Cane River, Red River, Old River (Natchitoches Parish), and Bayou Brevelle (named after Jean Baptiste Brevel). Isle Brevelle was considered "the richest cotton-growing portion of the south". Father Yves-Marie LeConiniat, a priest from France, referred to it as an "earthly paradise".[4][5]

Isle Brevelle is a featured destination on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail with over 60 cultural, religious, architectural, and historically significant African, Native American, and Creole sites including St. Augustine Parish Church, Melrose Plantation, Badin-Roque House and burial sites of Louisiana Creole people and Native Americans of the Adai, Natchitoches, and Hasinai tribes of the Caddo Confederacy. The Cane River National Historical Area has designated a cultural trail, the Isle Brevelle Trail, to highlight the birthplace of Creole culture[6]

History

[edit]The Louisiana Creole community is made of descendants of French and Spanish colonials, Africans, Anglo-Americans, and Native Americans of the Caddo Confederacy (Natchitoches, Adai).[7][8]

Isle Brevelle is named after Jean Baptiste Brevelle II (French: Jean Baptiste Brevel II.), its earliest settler and the 18th-century explorer and soldier of the Natchitoches Militia.[9] He is the son of Jean Baptiste Brevelle, a Parisian-born trader and explorer, and his Adai Caddo (French: Natao) Native American wife, Anne Marie des Cadeaux. The baptism of Jean Baptiste Brevelle II is recorded on May 20, 1736 in the oldest Catholic Registry in the Louisiana colony.[10] Jean Baptiste Brevelle II was granted the island by David Pain, the subdelegate at Natchitoches in 1765 for his service to the French and Spanish crowns as a Caddo translator and explorer of Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico.[9]

As the colony changed hands from France to Spain, the spelling of the Brevel surname changed to Brevelle. Records kept by the Spanish Crown (and later by the United States of America after the Louisiana Purchase) changed the names of the Brevelle family members to reflect the new spelling: Jean Baptiste Brevelle. The Brevelle Plantation grew to become one of the largest plantations in the South producing cotton, tobacco, indigo, lumber, bear grease, cattle, and food crops.[11]

Nicolas Augustin Metoyer (1768–1856), was the son of Marie Thérèse Coincoin and Claude Thomas Pierre Métoyer, and he has been considered the "grandfather" of the community of Isle Brevelle.[12] He was born into slavery and remained in bondage (initially to Don Manuel Antonio de Soto y Bermúdez, and wife Marie des Nieges de St. Denis DeSoto)[13] until 1792, at the age of 24.[12] Around this same time his mother, Marie Thérèse Coincoin was also freed from enslavement and they, as a family started collecting local land, which eventually amassed to 6,000 acres.[12] At the center of this collected land was Isle Brevelle (formerly the Brevelle Plantation).[12] During this era and in this location, mulatto people lived similarly to white Southern planters, in large mansions with expensive furniture, and in some cases they held their own slaves.[12] Nicolas Augustin Metoyer's home no longer stands, but the church he built, St. Augustine Parish still does.[12]

St. Augustine Parish Church

[edit]

St. Augustine Parish Church (or Isle Brevelle Church) was established as a mission church by Creole Nicolas Augustin Metoyer and other prominent Creole families of Isle Brevelle, St. Augustine is celebrated as the first church in Louisiana to be built by and for free people of color.[14] Augustin's father, Claude Thomas Pierre Metoyer had taken him to France in 1801 to visit his homeland. While there Augustin was struck by the arrangement of the French villages where community life was centered about the church. Upon his return to the Isle Brevelle and with the help of the Creoles of Isle Brevelle, the first church was constructed in 1803 using their own money and land.[15][16] Tradition also describes the role of Augustin's brother Louis (founder of the nearby Melrose Plantation, a National Historic Landmark), as the chapel's designer and builder.[17] As a means of collecting money for the church in earlier times, families of the parish were required to rent pews for their personal use and to donate religious items. Name boxes where attached at the end of each pew which allowed its owner exclusive use, even if the church was full. The blessing of the church was done by Fr. J. B. Blanc on July 19, 1829 under the title of St. Augustine, the patron saint of Augustin Metoyer. At this time, the church was to be a mission of St. Francois of Natchitoches.[18]

On March 11, 1856, the mission of St. Augustine at Isle Brevelle was decreed by Bishop Auguste Martin, the 1st Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Natchitoches, to be a parish in its own right and assigned his brother, Fr. Francois Martin to be its first resident pastor.[19] With the financial backing of Creole families Metoyer, Brevelle, Guidry, Balthazar and Roques, St. Augustine expanded to found four mission churches in the area: St. Charles Chapel at Bermuda, St. Joseph's Catholic Mission at Bayou Derbonne, St. Anne Chapel at Old River, and St. Anne Church (Spanish Lake).[18][20]

In 1913 under Bishop Van de Van, the order of Holy Ghost Fathers took charge of the parish and remained until 1990. The dedication of the existing church structure by Bishop Van De Van was at a solemn high mass on February 15, 1917 with Fr. J. Baumgartner as its pastor.[18]

Schools and convents

[edit]In 1856, the Daughters of the Cross convent were invited to establish a school on Isle Brevelle called Saint Joseph's School. The nuns had established a convent and school the previous year in Avoyelles Parish named the Presentation School. Mother Superior Hyacinthe LeConniat wrote to her brother of the Isle Brevelle Creoles, “These are people of leisure and many of wealth and means. The Bishop bought us a house with sixty acres of land there.” The Daughters of the Cross expanded to operate 5 schools in Louisiana and relied heavily on donations from wealthy Creole families such as the Prud’homme, Metoyer, and Brevelle's. The Brevelle family with plantations along the Red River at Grand Ecore, Isle Brevelle, and Marksville Brouillette (Avoyelles) provided funds, food, and religious artifacts for both the Presentation School and Saint Joseph's, which their children and those of their workers attended.[21][22] By 1859 the school listed between 120 and 130 girls. Additional nuns were brought in as enrollment continued to rise. A larger school, Saint Joseph's, and a convent were built closer to St. Augustine Church. The school flourished through 1862, until the effects of the Civil War resulted in a plummeting enrollment; in December 1863, the convent was closed, and the nuns were called home to the Avoyelles.[23]

St. Genevieve Catholic Church of Brouillette

[edit]In addition to the Daughters of the Cross Presentation School in Avoyelles Parish, the descendants of Isle Brevelle founder were amongst the founding patron families (Brevelle, Ponthier, Bordelon and Lachney) of the St. Genevieve Catholic Church of Brouillette. Their names appear prominently at the entrance of the church and its iconic cemetery with above-ground tombs. Brouillette is a small Creole community located on the banks of the Red River approximately 80 miles southeast of Natchitoches. St. Genevieve is a parish church of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Alexandria.[24]

Brevelle station

[edit]While railways had changed the commercial nature of agriculture and passenger service throughout the country beginning in the 1830s, the Cane River region was late in attracting the large investments of capital that rail service required. The area did not see rail service until well after the end of the Reconstruction era (after the Civil War). Among the early railroads established in Natchitoches Parish was the Natchitoches Railroad, established in 1887. By 1898, it was operating as the Natchitoches & Red River Valley Railway, which lasted until 1901, when it was incorporated into the larger Texas and Pacific Railway. One of the stops on the 32-mile-long railroad line, which stretched from the City of Natchitoches to Grand Encore, was the Brevelle Station. Oral tradition by the members of the Prud’homme family states that Alphonse I constructed the wood-frame Brevelle Station depot. Alphonse II recalled that “Grandpa Alphonse had built a place there, so they put a side track there [to] pick up cotton, or anything that had to be shipped.” The depot continued to serve as a stop on the Texas and Pacific Railroad until it was destroyed in a fire in 1914. In 1915, the Texas and Pacific Railway Company petitioned the Railroad Commission for permission to discontinue service to the Brevelle Station. It was not until 1927 that the Texas and Pacific Railway constructed its still-extant depot in Natchitoches to service its spur to the city. The spur that connected Natchitoches to the main rail trunk had existed since at least 1903, according to the official Texas and Pacific map. However, neither Magnolia nor Oakland took advantage of railroad spur connections to facilitate transport of their goods to market, instead relying on road transport to transshipment points on the rail line or into the city of Natchitoches. Even though less efficient than direct connections to the railroad, this was still much quicker and easier than transporting goods on the Cane River.[25]

Representation in literary work

[edit]- Cane River (Isle Brevelle) Community and its Inhabitants 1722–1982 (1989): Published by the Cammie G. Henry Research Center at Northwestern State University, this book focuses on the early inhabitants of Isle Brevelle to include the displaced Native Americans of the Natchitoches Tribe shortly after the founding of nearby Fort St. Jean Baptiste des Natchitoches.[26]

- Isle of Canes (2004): Elizabeth Shown Mills' historical novel, draws upon her many years of research.[27] She explores multiple generations of a Creole Louisiana family,[28] which includes the founding of St. Augustine Church, and the religious leadership of the Isle Brevelle community.

- Natchitoches and Louisiana’s Timeless Cane River (2002): Philip Gould's photography book spotlights the Creole settlement of Isle Brevelle. Gould celebrates the music, food, folklore, architecture, and landscape of this vibrant multiethnic community. Harlan Mark Guidry, one of the many descendants of Isle Brevelle now living throughout the United States, narrates the story of this unique cultural treasure.[29][30]

- The Collected Works of Ada Jack Carver (1980): Author Ada Jack Carver shares an anthology containing thirteen short stories and a one-act play about the Cane River people, and their unique Southern culture.[31][32]

- Recipes from the Isle - Isle Brevelle, Louisiana Cookbook (1999): a Creole cookbook featuring recipes from members of the St. Augustine Catholic Church.[citation needed]

- That Was Then: Memories of Cane River (2017): Isle Brevelle resident and photographer Joseph Moran's photography book on the historic settlement of Cane River.[citation needed]

Representation in film

[edit]- Cane River: The Isle Brevelle Church is depicted in the 1982 historical romantic drama Cane River, which was lost for decades before being rediscovered a distributed digitally and in theaters beginning in 2020.[citation needed]

- Steel Magnolias: Several scenes from the 1989 American comedy-drama film Steel Magnolias directed by Herbert Ross and starring Academy Award winners Sally Field, Shirley MacLaine, and Olympia Dukakis with Dolly Parton, Daryl Hannah, and Julia Roberts were shot on Isle Brevelle. Character Shelby's wedding was filmed at St. Augustine Church.[33] The film is an adaptation of Robert Harling's 1987 play of the same name about the bond a group of women share in a small-town Southern community, and how they cope with the death of one of their own. The supporting cast features Tom Skerritt, Dylan McDermott, Sam Shepard and Kevin J. O'Connor.[34]

- The Horse Soldiers: The Horse Soldiers is a 1959 American adventure war western film set during the American Civil War directed by John Ford and starring John Wayne, William Holden and Constance Towers. The screenplay by John Lee Mahin and Martin Rackin was loosely based on Harold Sinclair's 1956 novel of the same name, a fictionalized version of Grierson's Raid in Mississippi. Portions of the movie were filmed on Isle Brevelle including scenes of the plantation house.[34]

- The Man in the Moon: The Man in the Moon is a 1991 American coming of age drama film. It stars Reese Witherspoon in her film debut, Sam Waterston, Tess Harper, Emily Warfield, and Jason London.The film’s story, set in rural 1950s Louisiana, centers around Dani (Witherspoon), a 14-year-old tomboy who experiences first love and heartbreak when older boy Court (London) moves next door. Portions of the movie were filmed on Isle Brevelle.[34]

- For Sale by Owner: For Sale by Owner is a 2009 horror film starring Scott Cooper and Rachel Nichols, with supporting performances by Tom Skerritt, Skeet Ulrich, Frankie Faison, and Kris Kristofferson filmed on Isle Brevelle.[35]

- Clementine Hunter’s World: Clementine Hunter’s World is a 2016 documentary filmed on Isle Brevelle featuring life along the banks of the Cane River and colorful paintings of self-taught, primitive artist Clementine Hunter.[34]

- Texas Before the Alamo: is a 2018 Lone Star EMMY Awards Finalist that was directed by William E. Millet (from Dallas, Texas) and narrated by Jorge Nuñez (Univision 41, from Mexico City) and filmed at historic locations in Mexico, Texas and Louisiana including Isle Brevelle. The 8-hour series was broadcast in ten segments on Univision 41 Television as a part of the San Antonio Tricentennial SA300.[36][37]

Cemeteries and burial sites

[edit]There are numerous historically significant cemeteries and Native American burial sites on Isle Brevelle.[citation needed] Natchitoches and Adai Native Americans are buried on the isle including a cemetery near Bayou Brevelle at the old Brevelle Plantation and the St. Augustine Catholic Cemetery.[citation needed] Enslaved persons who died at Bermuda Plantation were buried in a cemetery on Prud’homme property, also near Bayou Brevelle.[citation needed] Some slave burial markers included wrought iron crosses, such as those attributed to Bermuda’s blacksmith, Solomon Williams.[38]

Notable places

[edit]

- Badin-Roque House

- Cane River Lake

- Cherokee Plantation (Natchez, Louisiana)

- Coincoin–Prudhomme House (or Maison de Marie Thérèse)

- Oakland Plantation (Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana)

- Magnolia Plantation (Derry, Louisiana)

- Melrose Plantation

- Bayou Brevelle

- Kate Chopin House (Cloutierville, Louisiana)

- Guy House (Natchitoches, Louisiana)

- Caspiana Plantation Store

- St. Augustine Parish (Isle Brevelle) Church

Notable people

[edit]- Anne des Cadeaux (unknown–1754), former Native American slave, mother of Jean Baptiste Brevelle II, and buried on Isle Brevelle at the Brevelle Plantation.

- Jean Baptiste Brevelle (1698–1754), early 18th-century French explorer, trader and soldier of Fort Saint Jean Baptiste des Natchitoches. Husband of Anne des Cadeaux.[39]

- Jean Baptiste Brevelle II (1730–1806), explorer, translator and soldier

- Robert Brevelle (born 1977), entrepreneur, venture capitalist and professor,[40] is a lineal descendant of Isle Brevelle founder Jean Baptiste Brevelle II and Anne des Cadeaux.

- Marie Thérèse Coincoin (1742–1816), a planter, former slave turned slave owner, and businesswoman on Isle Brevelle.

- Kellyn LaCour-Conant, restoration ecologist[41]

- Clementine Hunter (c. 1887–1988), self-taught folk artist, she lived at the Melrose Plantation within Isle Brevelle.[42]

- Billie Stroud (1919–2010), self-taught folk artist, used Isle Brevelle as one subject of her work and spent time there.[43]

See also

[edit]- National Register of Historic Places listings in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana

- Basilica of the Immaculate Conception (Natchitoches, Louisiana)

- Brevelle Lake

- John Sibley (doctor)

- Louisiana Purchase

- Great Raft

- Caddo

References

[edit]- ^ Dowdy, Verdis (5 October 1975). "Isle Brevelle and Festival". Newspapers.com. The Town Talk. p. 7. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ^ Gregory, H. F. "Isle Brevelle". Louisiana Regional Folklife Program, Northwestern State University.

- ^ a b "Cane River Creole Community". Louisiana Regional Folklife Program, Northwestern State University.

- ^ McCants, Sister Dorothea Olga (1970). They Came to Louisiana: Letters of a Catholic Mission. LSU Press. pp. 122–125. ISBN 0807109037.

- ^ Mills, Gary (1977). The Forgotten People: Cane River's Creoles of Color. LSU Press. p. 51. ISBN 0807137138.

- ^ "Cane River National Heritage Trails Map" (PDF). Cane River National Heritage Area. Cane River National Heritage Area, Inc. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

- ^ "Cane River Creole Community". Louisiana Regional Folklife Program. Northwestern State University (NSULA). Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "History". Brevelle Conservation Trust. 13 April 2020. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ^ a b Mills, Gary B.; Mills, Elizabeth Shown (2013). The Forgotten People: Cane River's Creoles of Color. LSU Press. pp. 50–67. ISBN 9780807137130 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mills, Elizabeth Shown (2007). Natchitoches. Abstracts of the Catholic Church Registers of the French and Spanish Post of St. Jean Baptiste des Natchitoches in Louisiana 1729-1803. Cane River Creole series. New Orleans, Louisiana: Heritage Books Inc. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0931069109.

- ^ "History Brevelle Conservation Trust". 13 April 2020. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ^ a b c d e f Dowdy, Verdis (21 September 1975). "Discovering Cenla, Grandpere, a Church, and a Portrait". Newspapers.com. The Town Talk. p. 43. Retrieved 2021-06-27.

- ^ Chrysler-Stacy, Elizabeth M. (1994). "Marie des Nieges de St. Denis DeSoto: Mother of De Soto Parish". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 35 (3): 350–354. ISSN 0024-6816. JSTOR 4233129.

- ^ "Church once featured in Steel Magnolias was first Black-founded, financed, and attended church for Catholics in the U.S." KTALnews.com. 2023-12-19. Retrieved 2024-01-15.

- ^ Cane River Creole National Historical Park: Historic Resource Study 2019 (PDF). US National Park Service (Report). Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. & Suzanne Turner Associates. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Fr. J.B. Blanc, Reg. 6: 116. For a lengthy analysis of the evidence surrounding the construction of the chapel; see Gary B. Mills, The Forgotten People: Cane River's Créoles of Color (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 197), 145–150.

- ^ Clyde Roque, "St. Augustine Church", Diocese of Alexandria, accessed 15 Jul 2008. [better source needed][dead link]

- ^ a b c "History of St. Augustine Catholic Church". St. Augustine Catholic Church. [better source needed]. Roman Catholic Church. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Bishop Auguste Martin". Diocese of Alexandria. Roman Catholic Church. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "Creoles in the Cane River Region", Cane River National Heritage Area: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary, National Park Service, accessed 15 Jul 2008

- ^ "Daughters of the Cross Series". Diocese of Shreveport. Catholic Collection Magazine. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ "Mother Mary Hyacinth". 64 Parishes Magazine. 64 Parishes Magazine. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Cane River Creole National Historical Park: Historic Resource Study 2019 (PDF). US National Park Service (Report). Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. & Suzanne Turner Associates. pp. 4-20 to 4-23. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ "Alexandria Diocese Parishes". Diocese of Alexandria. [better source needed]. Roman Catholic Church. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Cane River Creole National Historical Park: Historic Resource Study 2019 (PDF). US National Park Service (Report). Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. & Suzanne Turner Associates. p. 7-10 to 7-50. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Cane River (Isle Brevelle) Community and its Inhabitants 1722-1982. [better source needed]. Northwestern State University. 1989. ASIN B00073EOCK.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Delta native pens Southern adventures". Hattiesburg American. 2004-08-16. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-04-15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hines, Regina (2004-05-16). "Novel explores Creoles of Cane River". Sun Herald. p. 62. Retrieved 2024-04-15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Gomez, Gay M. (2004). "Review of A River and Its City: The Nature of Landscape in New Orleans". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 45 (3): 359–361. ISSN 0024-6816. JSTOR 4234043.

- ^ "Picture Perfect: Photographer offers view of Cane River". The News-Star. 2002-11-08. p. 42. Retrieved 2024-04-15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Award-Winning Writer Featured". The Town Talk. 1980-09-05. p. 10. Retrieved 2024-04-15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Author to Be In Natchitoches". The Town Talk. 1980-10-29. p. 28. Retrieved 2024-04-15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ross, Herbert (1989-11-22), Steel Magnolias (Comedy, Drama, Romance), TriStar Pictures, Rastar Films, retrieved 2023-01-12

- ^ a b c d "Natchitoches Film Trail". Official City of Natchitoches Site. Natchitoches Office of Tourism. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Jason Buchanan (2013). "For Sale by Owner". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-12-20.

- ^ "'TEXAS BEFORE THE ALAMO': A FILM AND HISTORY SYMPOSIUM OF SPANISH TEXAS". University of Houston. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ ""TEXAS BEFORE THE ALAMO" FILM WILL BE PREMIERED AT LATINO CULTURAL CENTER". Dallas Culture. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Cane River Creole National Historical Park: Historic Resource Study 2019 (PDF). US National Park Service (Report). Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. & Suzanne Turner Associates. pp. 4–17. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ "Summary Report: Isle Brevelle". United States Geological Service. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ Whitney, Amber (September 2023). "Robert Brevelle CEO". thetop100magazine.com. p. 64. Retrieved 2021-12-18.

- ^ "Kellyn LaCour-Conant, MSc Tales from the Trail: Adventures in Restoration Ecology – McWane Science Center". Retrieved 2023-01-08.

- ^ Catlin, Roger. "Self-Taught Artist Clementine Hunter Painted the Bold Hues of Southern Life". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Register, James (6 January 1974). "Isle Brevelle Produces a New Primitive". Newspapers.com. The Town Talk. p. 29. Retrieved 2021-06-27.

Further reading

[edit]- Gould, Philip (2002). Natchitoches and Louisiana's Timeless Cane River. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807128329.

- African-American history of Louisiana

- Cane River National Heritage Area

- Louisiana African American Heritage Trail

- Louisiana Creole culture in New Orleans

- Unincorporated communities in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana

- Plantations in Louisiana

- Populated places in Ark-La-Tex

- Unincorporated communities in Louisiana

- Populated places in Louisiana established by African Americans