Giganhinga

| Giganhinga Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Suliformes |

| Family: | Anhingidae |

| Genus: | †Giganhinga Rinderknecht & Noriega, 2002 |

| Type species | |

| †Giganhinga kiyuensis Rinderknecht & Noriega, 2002

| |

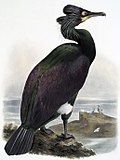

Giganhinga is a genus of giant darter that lived during the Late Miocene to Early Pleistocene in what is now Uruguay and Argentina. The largest species of anhinga known to science, estimates suggest it may have weighed around 17.7 kg (39 lb) and was likely flightless. Its weight likely helped it dive for prey and the anatomy of the pelvis indicates that it was a good and maneuverable swimmer. Only a single species is currently recognized, G. kiyuensis.

History and naming

[edit]Giganhinga was described by Rinderknecht and Noriega in the year 2002 based on specimen MNHN 1632, an incomplete pelvis. Due to the fossils immense size and weight, it was at first thought to belong to a terror bird before it was identified as an anhinga. The exact stratigraphic layer of Giganhinga is unknown, as there are three outcrops present in the region where the fossil has been found. These three outcrops belong to the Camacho Formation, the San José Formation and the Libertad Formation. However, based on sand and gravel attached to the fossil Rinderknecht and Noriega rule out both the Camacho and Libertad Formations, concluding that the material could only stem from the Pliocene to Pleistocene sediments of the San José Formation. Another indication of this is the colour of the fossil. Although most of the surface has taken on a darker coloration, areas filled with sand managed to preserve its original colour, which is pinkish and thus matches those of other fossils from the San José Formation.[1] A second specimen, the distal end of an enormous femur, was found in the Argentinian Ituzaingó Formation and tentatively assigned to cf. Giganhinga based on its massive size.[2]

The name Giganhinga is a combination of the Greek "gigas" (γίγας) meaning giant and the name Anhinga, which is the genus including all modern darter species (and itself derives from the Tupi language and means "devil bird" or "snake bird"). The species name "kiyuensis" is based on the beach of Kiyü, a balneario in southern Uruguay on the Rio de La Plata.[1]

Description

[edit]

The holotype pelvis of Giganhina is somewhat deformed and heavily eroded, having lost most of its original texture and its original colour and having undergone remineralisation. The pelvis is notably more robust than those of any extant or extinct darter species and has strong attachment points for musculature while lacking pneumatization. In addition to being incredibly robust, the fossil is also of large size, approximately 500% larger than the known material of the second-largest anhinga species, Macranhinga paranensis. The cranial section of the synsacrum is composed of strongly united vertebrae which are taller than they are wide and laterally compressed, said compression growing more pronounced further up the vertebral column. However this compression is relatively less developed than in cormorants and other anhingas. Like other anhingas, the first vertebra of the synsacrum is opisthosacral. The ventral margin of the synsacrum remains parallel to the axis of the body while opposing the first two vertebrae, only to project more dorsally with the onset of the third vertebra, creating an angle in the bone similar to what is observed to other South American fossil anhingas. At the level of the sacral vertebrae there is a notable fossa which is deeper towards its caudal end similar to Anhinga but not as developed as in either Meganhinga or Macranhinga. The type material shows six preacetabular foramina on each side of the fossil, growing smaller in diameter the further back they are located and with a somewhat larger gap between the last two foramina. The socket that received the femur is closed and notably enlarged and the space between these cavities (of which only one is preserved) is located further ventrally than in the relatives of Giganhinga. The neural spine before the sockets is higher than in any other suliform and gradually decreases in height as it approaches the acetabulum, bifurcating over the socket and ending in two robust postrochanteric processes. This process too is higher than in Anhinga and even Meganhinga and terminates further back than in either of these two taxa, bearing a closer resemblance to Macranhinga. The antitrocanter has a large surface and is oriented in a more perpendicular fashion relative to the synsacrum.[1]

The femur recovered from Argentina shows an intermediate condition between anhingas and cormorants with a more robust shaft and wider distal end. Like the holotype, this fossil exceeds the size of the corresponding bone in any other known anhinga species, which is the main reasoning behind its tentative referral to Giganhinga, as there is no overlap between the material. Meanwhile, the bone does resemble material known from Macranhinga, if many times the size of any known material belonging to said genus. [2]

A common way to calculate mass estimates in fossil birds is by utilizing the measurements and proportions of the limb bones. Although such a direct approach is not possible in Giganhinga in the absence of limb material, Rinderknecht and Noriega nevertheless calculated the weight based on the proportions of Macranhinga. They recovered three results based on the specific region used in their calculations with a mean result of 25.7 kg (57 lb), heavier than any other extinct or extant member of the family and almost five times as heavy as the next-big fossil darter.[1] In a 2007 paper; Areta, Noriega and Agnolin argue that these results vastly overestimate the weight of Giganhinga, noting that the lack of a similarly sized equivalent makes accurate estimates difficult. Their results, based on the modern American anhinga rather than extinct taxa, suggests a weight of 12.8 kg (28 lb), only half the mass of previous estimates. Calculating the weight of the Argentinian specimen resulted in an estimated mass of 17.7 kg (39 lb). However the authors still treat these results with caution, as they exceed the average weight of other swimming birds.[2] In life Giganhinga may have stood around 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall.[3]

Classification

[edit]Phylogenetic analysis conducted by Guilherme and colleagues in 2020 recovered that Giganhinga is closely related to the large-bodied species of the genus Macranhinga. Notably however, Giganhinga is the found to be the sister taxon to Macranhinga ranzii specifically with M. paranensis occupying a more basal position. This renders Macranhinga paraphyletic and may suggest that Giganhinga and Macranhinga are synonyms,[4] however additional research is required to determine this relationship with certainty. The consensus tree of the results by Guilherme and colleagues is figured below: [5]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

[edit]The immense size of Giganhinga may have played an important role in its foraging behavior, as its weight would have decreased buoyancy and allowed it to dive to greater depths relative to other anhinga species, which are typically shallow water divers.[6] A similar conclusion was found for Macranhinga previously. The idea that the size increase is an adaptation to swimming and diving is supported by the anatomy of the antitrocanter, which serves to counteract the forces produced by kicks that birds use while propelling themselves underwater. Subsequently, a stronger antitrocanter suggests that Giganhinga performed strong kicks associated with locomotion in water. The antitrocanter also forces the femur into a closer and more parallel position to the rest of the body, which is likewise advantageous for swimming. The caudal musculature of Giganhinga may have allowed for stronger movement of the tail allowing the bird to more effectively steer while diving.[1] Given its size and weight Giganhinga was possibly flightless.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Rinderknecht, A.; Noriega, J.I. (2002). "Un nuevo género de Anhingidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) del Plioceno–Pleistoceno del Uruguay (Formación San José)". Ameghiniana. 39 (2): 183–191. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-05-09. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

- ^ a b c Areta, J. I.; Noriega, J. I.; Agnolin, F. (2007). "A giant darter (Pelecaniformes: Anhingidae) from the Upper Miocene of Argentina and weight calculation of fossil Anhingidae". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 243 (3): 343–350. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2007/0243-0343. hdl:11336/80812.

- ^ "Cuando volaban aves gigantes sobre Uruguay". El Observador. 15 November 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Diederle, Juan Marcelo (2015). Los Anhingidae (Aves: Suliformes) del Neógeno de América del Sur: sistemática, filogenia y paleobiología (Tesis thesis) (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Archived from the original on 2020-01-02. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ Guilherme, E.; Souza, L. G. D.; Loboda, T. S.; Ranzi, A.; Adamy, A.; Dos Santos Ferreira, J.; Souza-Filho, J. P. (2020). "New material of Anhingidae (Aves: Suliformes) from the upper Miocene of the Amazon, Brazil". Historical Biology. 33 (11): 1–10. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1850714. S2CID 230599234.

- ^ a b Mayr, G.; Lechner, T.; Böhme, M. (2020). "The large-sized darter Anhinga pannonica (Aves, Anhingidae) from the late Miocene hominid Hammerschmiede locality in Southern Germany". PLOS ONE. 15 (5): e0232179. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1532179M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0232179. PMC 7202596. PMID 32374733.