Fawley Power Station

| Fawley Power Station | |

|---|---|

Fawley Power Station in 2012 | |

| |

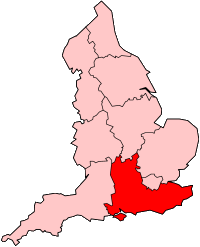

| Country | England |

| Location | Hampshire, South East England |

| Coordinates | 50°49′00″N 1°19′44″W / 50.816696°N 1.328881°W |

| Construction began | 1965 |

| Commission date | 6 May 1971[1] |

| Decommission date | 31 March 2013[2] |

| Owners | Central Electricity Generating Board (1971–1990) RWE npower (1990–2013) |

| Operators | Central Electricity Generating Board (1971–1990) RWE npower (1990–2013) |

| Thermal power station | |

| Primary fuel | Oil-fired |

| Secondary fuel | Fuel oil for auxiliary gas turbines |

| Chimneys | 1 (198 m) |

| Cooling towers | None |

| Cooling source | Sea water |

| Power generation | |

| Units operational | 4 × 500 MW |

| Annual net output | 5271.594 GWh (Year 1980/81) |

grid reference SU473021 | |

Fawley Power Station was an oil-fired power station located on the western side of Southampton Water, between the villages of Fawley and Calshot in Hampshire, England. Its 198-metre (650 ft) chimney was a prominent (and navigationally useful) landmark.

Overview

[edit]The station, which in its final years was owned and operated by Npower, was oil-fired, powered by heavy fuel oil. Pipelines connected the station to the nearby Fawley oil refinery. There were two 10-inch (25 cm) diameter, 3.2-kilometre (2.0 mi) long, pipelines which discharged into storage tanks with a capacity of 24,000 tonnes.[3] Due to oil being more expensive than other fuels such as coal and natural gas, Fawley did not operate continuously, but came on line at times of high demand.

It was also connected to the National Grid with circuits going to Nursling and a tunnel under Southampton Water to Chilling then to Lovedean with a local substation at Botley Wood.

A dock was included in the construction, to allow for the delivery of oil by sea; however, after one ship delivery (essentially a trial) this facility remained disused.

History

[edit]Fawley was one of the Hinton Heavies, and was built by Mitchell Construction Architect Colin Morse RIBA[4] for the CEGB between 1965[5] and 1969.[6] It was commissioned in 1971 as a 2,000-megawatt (MW) power station, with four 500 MW generating units, each consisting of a boiler supplying steam to a turbine that powers an associated generator.

The boilers were capable of delivering 1,788.0 kg/s of steam at 158.6 bar and 538 °C.[7] The cooling pumps were Britain's largest with a flow of 210,000 GPM. One was driven by an experimental super-conducting electric motor.

In 1978/79 Fawley was presented with the Hinton Cup, the CEGB's "good house keeping trophy". The award was commissioned by Sir Christopher Hinton, the first chairman of the C.E.G.B. It was the first time that a C.E.G.B region (South West) had won both the Hinton Trophy and Hinton Cup. The cup going to the Solent transmission district.[8]

The operating data for the main plant is shown in the table:[9]

| Year | Net capability, MW | Electricity supplied, GWh | Load as percent of capability, % | Thermal efficiency, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 2,000 | 7,059.640 | 48.5 | 34.38 |

| 1979 | 1,932 | 10,047.995 | 59.4 | 35.53 |

| 1981 | 1,932 | 5,271.594 | 31.1 | 34.24 |

| 1982 | 1,932 | 4,723.965 | 27.9 | 36.87 |

| 1984 | 1,932 | 2,007.425 | 11.8 | 34.27 |

| 1985 | 1,932 | 12,980.721 | 76.7 | 37.87 |

| 1986 | 1,932 | 2,110.406 | 12.5 | 35.18 |

| 1987 | 1,932 | 4,234.020 | 25.0 | 36.223 |

The electricity output, in GWh, is shown graphically:

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

The high output in 1984/5 as associated with the 1984/5 Miners' Strike, and the shortage of coal for coal-fired power stations. There were also 4 × 17.5 MW auxiliary gas turbine generators on the Fawley site giving a total output of 70 MW, these machines had been commissioned in September 1969.[7][10]

Two units were mothballed in 1995,[11] leaving the station with a capacity of only 1,000 MW.

Proposed Fawley B station

[edit]CEGB plans for a coal-fired Fawley B station were not pursued following privatisation of the industry in the late 1980s.

Closure

[edit]On 18 September 2012, RWE npower announced they would be shutting down Fawley power station by the end of March 2013, due to the EU Large Combustion Plant Directive.[12] The power station was duly shut on 31 March 2013 after more than 40 years in operation.[13][2]

Impact on wildlife

[edit]When the plant was operating, the screens on the plant's cooling water lines were found to kill as many as 50,000 fish a week.[14] By the 1980s, intermittent plant operation meant that the annual kill total was around 200,000.[14] While this may have resulted in reduced numbers of some species such as bass, others such as sand smelt seemed unaffected.[14]

Use in media

[edit]

The unique round structure housing the control room for the station was used to represent the "World Control Center" building depicted in the 1975 film Rollerball.[15]

Some scenes for the 2015 film Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation were filmed on location at Fawley power station.[16]

The second series of British medical comedy Green Wing featured a scene that was shot in the control room.

The Red Dwarf series 11 episode "Give and Take" had a scene that was filmed inside the control room.[17]

The 2017 Channel 4 programme Spies filmed at the station and inside the control room.

The final episode Harvest of series 4 of Endeavour used the power station and control room.

The exterior of the power station was used as a filming location for the Star Wars film Solo: A Star Wars Story.[18]

The location was used as the extraction point for the 2018 series of Celebrity Hunted. The successful fugitives escaped by speedboat, exiting into Southampton Water.

Demolition and regeneration

[edit]In 2017 it was announced that the power station site would be turned into a "new town" consisting of 1,500 residential units, commercial and civic space, and a new school. The project went on display to the public on 27 September 2017.[19][20] The development has been referred to as Fawley Waterside, and was designed by Léon Krier, Ben Pentreath, and Kim Wilkie.[21] New Forest District Council approved the scheme in July 2020.[22] However, estate owner Aldred Drummond stepped down as CEO of the Fawley Waterside company in 2023, and the project was shelved in 2024.[23]

In June 2019, it was announced that the station would be demolished in several stages.[24] The first stage took place on 3 October 2019, with a controlled explosion of the turbine hall.[25][26] The southern section of the boiler house was demolished on 19 November 2020.[27] Demolition continued on 29 July 2021 with a further controlled explosion of the stations auxiliary buildings.[28] The chimney and remaining southern end of the turbine hall were demolished simultaneously at 7am on 31 October 2021.[29] In February 2023, demolition work began on the control building.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Tests at Fawley". New Scientist. Vol. 52, no. 774. Reed Business Information. 16 December 1971. ISSN 0262-4079. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ a b Franklin, James (1 April 2013). "Fawley Power Station in Hampshire closes after 40 years". Daily Echo. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Lester, R H (1973). "Industrial Development around the Esso refinery, Fawley". Geography. 58 (2): 154–59 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Indictment: Power & Politics in the Construction Industry, David Morrell, Faber & Faber, 1987, ISBN 978-0-571-14985-8

- ^ "Building of the month March 2015 - Fawley Power Station". The Twentieth Century Society. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Fawley Power Station chimney". Skyscraper Page. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b CEGB Statistical Yearbook. 1980-81. CEGB. London.

- ^ "Hinton Awards Made at Fawley". Power News (232): 3. November 1979.

- ^ CEGB Statistical Yearbooks 1971-1987. CEGB. London.

- ^ The Electricity Council (1990). Handbook of Electricity Supply Statistics. London: The Electricity Council. p. 8. ISBN 085188122X.

- ^ "Generation disconnections since 1991". National Grid. 2003. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^ "Power Stations To Be Closed Down By Npower". Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Fawley power station closes after 41 years". BBC News. 2 April 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Tubbs, Colin (1999). The Ecology, Conservation and History of the Solent. Packard Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 1853411167.

- ^ "Film Buffs may notice that the round control room was the World Control Centre in 1975 film Rollerball". Sam Farr/The Bath Chronicle.

- ^ Yandell, Chris (7 November 2014). "Scenes for Tom Cruise's Mission Impossible 5 will be filmed at Fawley Power Station in Hampshire". Daily Echo.

- ^ "Remembering 'landmark' Fawley Power Station ahead of demolition". BBC News. 30 October 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ Shaw, Aaron (24 May 2017). "PHOTOS: Behind the scenes shots as Star Wars films at Fawley Power Station". Daily Echo.

- ^ Yandell, Chris (27 September 2017). "Exhibition showcases plan to replace Fawley Power Station with 1,500 homes and luxury marina". Daily Echo.

- ^ Boyd, Alex (22 August 2020). "The staggering level of change at Fawley Power Station that will transform it into a neighbourhood". Hampshire Live. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Fawley Waterside". Ben Pentreath. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ Pitcher, Greg (30 July 2020). "Poundbury mastermind Leon Krier's south coast 'smart town' approved". Architects' Journal. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ Graham, Freya (6 March 2024). "The £2,300,000,000 'Venice of Britain' could be doomed to a watery grave". Metro. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ Yandell, Chris (1 June 2019). "Fawley power station to be destroyed in series of controlled explosions". Daily Echo. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Mohan-Hickson, Matthew (19 November 2019). "Fawley Power Station: Here is why you may have heard a loud bang in Hampshire this morning". Portsmouth News. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Yandell, Chris (4 October 2019). "Demolition experts begin operation at Fawley power station". Daily Echo. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Controlled explosion at Fawley Power Station felt from miles away". ITV News. 19 November 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Clark, Katie (29 July 2021). "Video of Fawley Power Station being blown up". Daily Echo. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Fawley Power Station: Chimney demolished as part of redevelopment". BBC News. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ Yandell, Chris (18 February 2023). "Fawley power station: Control room is being demolished". Daily Echo.

- Power stations in South East England

- Demolished power stations in the United Kingdom

- Former oil-fired power stations

- Former power stations in England

- Buildings and structures in Hampshire

- Buildings and structures destroyed in 2021

- 1971 establishments in England

- 2013 disestablishments in England

- The Twentieth Century Society Risk List

- Demolished buildings and structures in Hampshire

- Buildings and structures destroyed in 2019

- Buildings and structures destroyed in 2020

- Buildings and structures destroyed in 2023

- Energy infrastructure completed in 1969