F-Zero GX

| F-Zero GX | |

|---|---|

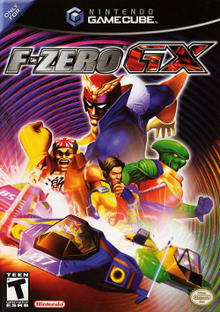

North American box art | |

| Developer(s) | Amusement Vision |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Producer(s) | Toshihiro Nagoshi Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Composer(s) | Hidenori Shoji Daiki Kasho |

| Series | F-Zero |

| Platform(s) | GameCube |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Racing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

F-Zero GX is a 2003 racing video game developed by Amusement Vision and published by Nintendo for the GameCube console. It runs on an enhanced version of the engine used in Super Monkey Ball. F-Zero AX, the arcade counterpart of GX, uses the Triforce arcade system board conceived from a business alliance between Nintendo, Namco and Sega. Published by Sega, it was released alongside GX in 2003.

F-Zero GX is the successor to F-Zero X and continues the series' difficult, high-speed racing style, retaining the basic gameplay and control system from the Nintendo 64 game. A heavy emphasis is placed on track memorization and reflexes. GX introduces a "story mode" element, where the player assumes the role of F-Zero pilot Captain Falcon through nine chapters while completing various missions.

The GX and AX project was the first significant video game collaboration between Nintendo and Sega. GX was well received by critics for its visuals, intense action, high sense of speed, and track design while its high difficulty has been criticized. In the years since its release it has been considered one of the GameCube's best titles, as well as one of the greatest video games ever made.

Gameplay

[edit]F-Zero GX is a futuristic racing game where up to thirty competitors race on massive circuits inside plasma-powered machines in an intergalactic Grand Prix.[1] It is the successor to F-Zero X and continues the series' difficult, high-speed racing style, retaining the basic gameplay and control system from the Nintendo 64 game.[2][3] Tracks include enclosed tubes, cylinders, tricky jumps, and rollercoaster-esque paths.[2][4] Some courses are littered with innate obstacles like dirt patches and mines.[4] A heavy emphasis is placed on track memorization and reflexes, which aids in completing the game.[2][3] Each machine handles differently,[5] has its own performance abilities affected by its weight, and a grip, boost, and durability trait graded on an A to E (best to worst) scale.[6] Before a race, the player is able to adjust a vehicle's balance between maximum acceleration and maximum top speed.[3] Every machine has an energy meter, which serves two purposes. First, it is a measurement of the machine's health and is decreased from accidents or attacks from opposing racers.[7] Second, the player is usually given the ability to boost after the first lap,[8] but must sacrifice energy to do so.[7] Pit areas and dash plates are located at various points around the track for vehicles to drive over. The former replenishes energy, while the latter gives a speed boost without using up any energy. The less time spent in the pit area, the less energy will regenerate.[8] Courses may also have jump plates, which launch vehicles into the air enabling them to cut corners.[9][8]

Each racing craft contains air brakes for navigating tight corners by using an analog stick and shoulder buttons.[10] Afterwards, the game's physics modeling give vehicles setup with high acceleration a boost of acceleration. Players can easily exploit this on a wide straight stretch of a circuit to generate serpentinous movements.[11] This technique called "snaking" delivers a massive increase in speed,[3] but it is best used on the easier tracks, when racing alone in Time Trial, and with heavy vehicles with a high grip rating and given high acceleration. According to Nintendo, the snaking technique was an intentional addition to F-Zero GX's gameplay.[12]

F-Zero GX features numerous gameplay modes and options.[9] In the Grand Prix mode, the player races against twenty-nine opponents through three laps of each track in a cup.[9] There are four cups available (Ruby, Sapphire, Emerald, and Diamond) with five tracks in each.[13][14] Unlocking the AX cup gives the player all six tracks from the arcade game, F-Zero AX.[15][16] Each cup has four selectable difficulty levels: Novice, Standard, Expert, and Master.[15] Players get a certain number of points for finishing a track depending on where they placed, and the winner of the circuit is the character who receives the most total points.[9] If the player has a "spare machine"—the equivalent of an extra life—then the race can be restarted even if the player's vehicle is destroyed from losing all energy or falling off the track. A predetermined number of spare machines based on the difficulty level chosen are given to players before starting a cup.[17] Players get an additional spare machine for every five contenders they destroy through vehicular combat,[18][8] with each destroyed and eliminated opponent also granting extra energy.[18]

The Vs. Battle is the multiplayer mode where two to four players can compete simultaneously. Time Attack lets the player choose any track and complete it in the shortest time possible.[19] An Internet ranking system was established where players enter a password on the official F-Zero website and get ranked based on their position in the database. Players receive a password after completing a Time Attack race, which records their time and machine used.[20] Ghost data, transparent re-enactments of the player's Time Attack performances, can be saved on memory cards to later race against. Up to five ghosts can be raced against simultaneously.[21] The Replay mode allows saved Grand Prix and Time Attack gameplay to be replayed with different camera angles and in-game music.[22] The Pilot Profile mode has each character's biography, theme music, information on their machine, and a short full motion video sequence.[23]

Customize mode is divided between the F-Zero Shop, Garage, and Emblem Editor. The shop is where opponent machines, custom parts for vehicle creation, and miscellaneous items such as story mode chapters and staff ghost data can be purchased with tickets. Tickets are acquired as the player progresses through the Grand Prix, Time Attack, and Story mode. In the Garage section, players can create a machine with three custom parts or print emblems on any vehicle. The parts are divided into body, cockpit, and booster categories, and affect the vehicle's overall durability, maximum speed, cornering, and acceleration. The Emblem Editor lets players create decals.[24]

F-Zero GX is the first F-Zero game to feature a story mode.[20] Its story has the player assume the role of F-Zero pilot Captain Falcon in nine chapters of various racing scenarios; such as Falcon's training regiment, a race against a rival through a canyon with falling boulders, attack and eliminate a rival's gang, and escape from a collapsing building through closing blast doors. Each chapter can be completed on a normal, hard, and very hard difficulty setting.[25] Toshihiro Nagoshi, one of the game's co-producers, stated that this mode was included because the development team felt that the F-Zero universe was unique and they wanted to explain some of the characters' motivations and flesh out the game world.[20]

Arcade counterpart

[edit]| F-Zero AX | |

|---|---|

F-Zero AX deluxe cabinet | |

| Publisher(s) | Sega |

| Platform(s) | Arcade |

| Release | |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

| Arcade system | Triforce |

F-Zero AX is a futuristic racing arcade game developed by Amusement Vision and published by Sega for the Triforce arcade system board.[28] It is the second game by Sega to use Triforce,[27] which was conceived from a business alliance between them, Nintendo and Namco.[29] This hardware allows for connectivity between the GameCube and arcade games.[26] F-Zero AX's arcade cabinet is available for purchase in standard and deluxe versions. The standard version is a regular sit-down model, while the deluxe version is shaped like Captain Falcon's vehicle and has a tilting seat simulating the craft's cockpit.[26][30] IGN demoed the Cycraft version dubbed "F-Zero Monster Ride" at the 2003 JAMMA arcade show. The Cycraft machine, co-developed between Sega and Simuline, is a cabin suspended in midair controlled by three servomotors for an in-depth motion-based simulation.[31]

The game features 14 playable vehicles with their pilots, consisting of ten newcomers and the four returning characters from the original F-Zero, as well as six race tracks.[26] Each track must be completed before time runs out. Time extensions are awarded for reaching multiple checkpoints on a course however, the player will receive time penalties for falling off-course or depleting their energy meter.[32] Two gameplay modes are available: Race mode, in which the player races against twenty-nine opponents; and Time Attack mode, in which the player attempts to complete a track in the fastest time possible.[33] Connecting multiple cabinets opens up "Versus Play" in the race mode, thus enabling up to four players to compete simultaneously.[32]

Data storage devices

[edit]F-Zero AX cabinets can dispense magnetic stripe cards called an "F-Zero license card" to keep track of custom machine data, pilot points, and race data. A card was bundled with the Japanese release of F-Zero GX. The card expires after fifty uses, but its data can be transferred to a new card.[26] Once inserted, the game builds a machine with three custom parts which can be upgraded by earning pilot points.[34] Pilot points are acquired as the player progresses through the Race and Time Attack modes.[32] Players can increase point earnings by improving finish place, eliminating opponents, and finishing races with a large amount of energy reserved.[26] A magnetic stripe card is needed to enter the F-Zero AX Internet Ranking system.[35] Similarly to GX,[20] players receive a password after completing a Time Attack race to enter on the official F-Zero website's ranking system.[36]

GameCube memory cards, on which saved games are kept, can be inserted into these arcade units.[37] A memory card is required for players a chance to win the AX-exclusive pilots, their vehicles, and tracks for use in GX.[38] Players can store up to four machines from GX on a memory card, then play them in AX. If a memory card is used with a magnetic stripe card, players have additional options; they can enter stored GX machines into the F-Zero AX Internet ranking system, and transfer custom AX machine parts to GX.[37] F-Zero AX content can also be acquired by completing GX's tougher challenges,[39][40] or through the use of a cheat device.[41]

Development and release

[edit]After Sega transitioned from first to third-party development in 2001,[42] they and Nintendo developed a close relationship.[43] Toshihiro Nagoshi, president of Sega subsidiary Amusement Vision, developed Super Monkey Ball for the GameCube, which opened up the opportunity for a collaboration between the two companies.[44] Nintendo announced on February 18, 2002, that an arcade system board under the name of "Triforce" was being developed in conjunction between Nintendo, Namco, and Sega.[29] The idea for the arcade board originated after discussions between Sega and Namco about the capabilities and cost effectiveness of the GameCube architecture to make arcade games.[45] Sega, having helped to develop Nintendo's Triforce arcade system, wanted to support it with software that would "stand out and draw attention to Nintendo's platform."[44] Nagoshi was suggested to develop a driving game and agreed under the stipulation he could come up with something unique—which was working on the next installment in Nintendo's F-Zero series.[44] Nagoshi contemplated declining the project due to the combined pressure of making a great impression on Nintendo and creating the next installment of an esteemed franchise, but his curiosity about what he and his team could create overcame his hesitation.[46]

"With Nintendo, it comes to a question of letting some other companies work on our franchises. We focus more on specific relationships with talented producers; we look for people who will care, spend a lot of time and energy, on a specific franchise. We also want to allow these producers to work on franchises that they are interested in working on."

— Shigeru Miyamoto, Nintendo EAD General Manager, The Nintendo/Sega Press Conference on July 7, 2003.[20]

In March 2002, an announcement from Sega and Nintendo revealed that Amusement Vision and Nintendo would collaborate to release F-Zero video game titles for the Triforce arcade board and the GameCube.[28][47][48] F-Zero GX and AX was the first significant software collaboration between Nintendo and Sega,[49] and the announcement that Nintendo had handled development of one of its franchises to former competitor Sega came as a surprise to some critics.[50][51] Nagoshi claimed that 1991's F-Zero "actually taught me what a game should be" and that it served as an influence for him to create Daytona USA and other racing games.[52] F-Zero producer Shigeru Miyamoto stated that Nintendo "gained a lot of fans among current game developers, including famous producers like Mr. Nagoshi who grew up playing Nintendo games and are big fans of some of our titles."[20] and thought the collaboration resulted in a "true evolution of the F-Zero series", enhancing the simulation of racing at high speeds and expanding the "F-Zero world on a grand scale."[53]

While Amusement Vision was responsible for most of the game's development,[44][54] Miyamoto and Takaya Imamura of Nintendo EAD took on the role of producer and supervisor, respectively.[55] Sega handled planning and execution and Nintendo was responsible for supervision of their product.[44] Nagoshi was initially concerned about differences in opinion between the two companies, and mentioned "If Nintendo planned to hold our hands through development, I would have suggested they develop the game themselves. That way we could focus on a project which would reflect our studio's abilities. I figured that would cause a war, but I was told most of the responsibility would be left to us."[44] F-Zero GX runs on an enhanced version of the engine used in Super Monkey Ball.[56] During the game's development, Nagoshi focused on what he called its self-explanatory "interface" and "rhythm" to give the way the tracks are laid out a rhythmic feel.[57] The game's soundtrack features an array of songs from rock and techno musical styles originally composed by the game music staff's Hidenori Shoji and Daiki Kasho.[58] Shojii is known for his musical scores in Daytona USA 2 and Fighting Vipers 2, while Kasho worked on the Gran Turismo series.[58] Kasho composed the character themes and their lyrics were by Alan Brey.[55] Both Shoji and Kasho supervised the soundtrack's audio mastering.[58]

Nintendo revealed the first footage of F-Zero GX at the Pre-Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) press conference on May 21, 2002. While the game was known to exist several months prior, it had remained behind closed doors until that conference.[59] In early March 2003, according to the official Nintendo website, F-Zero was delayed by two months.[60] Via a live video conference call from Japan on July 7, Miyamoto, Nagoshi, and Imamura answered questions about the two F-Zero games. There, Miyamoto announced the Japanese version of the game was finished and would soon be available to the public. Nagoshi mentioned that back at E3 2003, he was hoping that they would have that time to include a local area network (LAN) multiplayer mode, however they chose not to support this mode. The development team focused more on the game's single-player aspects, and a LAN multiplayer mode would distract greatly from it.[20] Imamura commented that even though he worked directly on F-Zero throughout its different incarnations, this time he took a "step back and was involved at kind of a producer level at looking over the game."[20] Imamura added "hav[ing] worked on the F-Zero series, and seeing the results of the collaboration with Sega, I found myself at something of a loss as to how we can take the franchise further past F-Zero GX and AX."[20]

Published by Nintendo,[28] F-Zero GX was released in Japan on July 25, 2003,[61] in North America on August 25,[62] in Australia on October 24,[63] and in Europe on October 31.[64] The Arcade version was released in 2003 alongside its Gamecube counterpart.[41] F-Zero GX/AX Original Soundtracks, a two-CD set composed of BGM soundtracks to the video games GX and its arcade counterpart, was released in Japan under the Scitron Digital Content record label on July 22, 2004.[65][66] The first disc consists of forty-one tracks and the second has forty with an additional track rearranged by Supersweep's AYA (Ayako Sasō) of "Big Blue".[58][66]

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 89/100[67] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Edge | 8/10[67] |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 9, 7.5, 7 of 10[68] |

| Eurogamer | 9/10[9] |

| Famitsu | 7, 8, 8, 9 of 10[69] |

| GamePro | 4.5/5[69] |

| GameSpot | 8.6/10[2] |

| IGN | 9.3/10[3] |

| PALGN | 81⁄2[70] |

| X-Play |

When F-Zero GX was released, the game was well-received overall by reviewers; the title holds an average of 89/100 on the aggregate website Metacritic.[67] Some video game journalists consider it as one of the best racers of its time and the greatest racer on the GameCube platform.[71][68] It was listed "Best GameCube Racing Game" in the E3 2003 IGN Awards and "Best Racing Game of 2003" by IGN.[72][73] F-Zero GX was named the best GameCube game of August 2003 and "Best GameCube Driving Game" of 2003 overall by GameSpot, and was nominated for "Console Racing Game of the Year" at the 7th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards held by the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences.[74][75][76] Official Nintendo Magazine ranked it the 92nd best game available on Nintendo platforms. The staff felt it was best for hardcore fans.[77] Edge ranked the game 66th on their 100 Best Video Games in 2007.[78]

The game has been credited for its visuals,[2][4] arcade/home connectivity, longevity, sharp controls, tough challenge,[79] and fleshed-out single-player modes.[4][68] The game's most common criticism is its difficulty, specifically in the game's story mode.[2][80] It earned fourth place in IGN's and GameTrailers' toughest games to beat.[79] GameTrailers mentioned F-Zero GX demanded players to master the "rollercoaster-style tracks [which] required hairline precision" to avoid falling off-course.[81] Electronic Gaming Monthly criticized GX's sharp increase in difficulty and GameSpot's Jeff Gerstmann agreed stating it "will surely turn some people away before they've seen the 20 tracks and unlocked all the story mode chapters".[2][68] Bryn Williams of GameSpy mentioned that "purists may find it too similar to [sic] N64 version" and criticized the lack of LAN play.[4]

1UP.com stated that the F-Zero series is "finally running on hardware that can do it proper justice".[82] Eurogamer's Kristan Reed pointed out that, graphically, "it's hard to imagine how Amusement Vision could have done a better job".[9] Matt Casamassina of IGN praised the developers' work commenting they have "done a fine job of taking Nintendo's dated franchise and updating it for the new generation" and summed up the general opinion by stating that "For some, GX will be the ultimate racer. For others, it will be flat out too difficult."[3] In Japan, F-Zero GX sold 100,981 units[83] and became qualified for the Player's Choice line in both Europe[84] and North America[85] by selling at least 250,000 copies.[86] Nagoshi said in a 2018 Edge interview that F-Zero GX sold over 1.5 million copies worldwide.[87]

References

[edit]- ^ Amusement Vision 2003, pp. 6–7, 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gerstmann, Jeff (2003-08-25). "F-Zero GX review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2007-01-26. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ a b c d e f Casamassina, Matt (2003-08-22). "F-Zero GX review". IGN. pp. 1–3. Archived from the original on 2010-12-16. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ a b c d e Williams, Bryn (2003-08-28). "F-Zero GX (GCN) review". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2006-12-12. Retrieved 2006-10-15.

- ^ a b Sessler, Adam (2003-09-30). F-Zero GX (GCN) Review (Video) (Television production). TechTV. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Amusement Vision 2003, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Pelland, Scott, ed. (2003). F-Zero GX Player's Guide. Redmond, Washington: Nintendo of America, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 1-930206-35-6.

- ^ a b c d Amusement Vision 2003, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f Reed, Kristan (2003-10-31). "F-Zero GX Review". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 2013-10-05. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ Torres, Ricardo (2003-07-08). "F-Zero GX Preview". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2003-07-24. Retrieved 2014-06-20.

- ^ Schneider, Peer. "Tips & Techniques". IGN. Archived from the original on 2006-10-18. Retrieved 2006-11-04.

- ^ IGN Staff (2003-08-06). "Fact or Fiction: The 10 Biggest Rumors on GameCube". IGN. Archived from the original on 2007-02-03. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ CVG Staff (2009-11-09). "F-Zero GX Review". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on 2013-10-05. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- ^ Schneider, Peer. "Track Strategies: Diamond Cup". IGN. Archived from the original on 2007-02-28. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- ^ a b Schneider, Peer. "Track Strategies". IGN. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- ^ Schneider, Peer. "Track Strategies: AX Cup". IGN. Archived from the original on 2009-07-31. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- ^ Amusement Vision 2003, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Amusement Vision 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Amusement Vision 2003, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i IGN Staff (2003-07-08). "F-Zero Press Conference". IGN. Archived from the original on 2007-02-14. Retrieved 2006-11-04.

- ^ Amusement Vision 2003, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Amusement Vision 2003, pp. 22, 24, 26.

- ^ Amusement Vision (2003-08-25). F-Zero GX (Nintendo GameCube). Sega. Level/area: Pilot Profiles.

- ^ Amusement Vision 2003, pp. 16, 27–29.

- ^ Pelland, Scott, ed. (2003). F-Zero GX Player's Guide. Redmond, Washington: Nintendo of America, Inc. pp. 76–95. ISBN 1-930206-35-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Torres, Ricardo (2003-07-03). "F-Zero AX Impressions". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

- ^ a b Yoshinoya, Bakudan (2003-02-21). "F-Zero AC at AOU". NintendoWorldReport. Archived from the original on 2009-02-10. Retrieved 2007-09-23.

- ^ a b c Satterfield, Shane (2002-03-28). "Sega and Nintendo form developmental partnership". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2009-02-13. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

The companies [Sega and Nintendo] are codeveloping two F-Zero games... Nintendo will be handling the publishing duties for the GameCube version while Sega will take on the responsibility of releasing the arcade game.

- ^ a b IGN staff (2002-02-18). "GameCube Arcade Hardware Revealed". IGN. Archived from the original on 2013-07-23. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ^ "F-Zero AX: Extreme High Speed Racing". Sega. Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ^ IGN Staff; Anoop Gantayat (11 September 2003). "Jamma 2003: F-Zero Monster Ride". IGN. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ^ a b c Sega, p. 61.

- ^ Sega, p. 61-62.

- ^ Mirabella III 2003, p. 2.

- ^ "Get connected with F-Zero AX". Official F-Zero GX/AX website. Archived from the original on 2003-08-25. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

In September, Sega and Nintendo will launch F-Zero AX in arcades throughout the country.

- ^ Sega, p. 69.

- ^ a b Mirabella III 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Mirabella III 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Schneider, Peer. "F-Zero GX Secrets". IGN. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ Schneider, Peer. "F-Zero GX Customization". IGN. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ a b Robinson, Andy (2013-03-08). "Full F-Zero AX arcade game discovered in GameCube version". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on 2014-12-01. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- ^ "Sega forecasts return to profit". BBC. 2001-05-22. Archived from the original on 2014-05-27. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ^ Burman, Rob (2007-03-29). "Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Games Interview". IGN. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ^ a b c d e f "Interview: Sega talk F-Zero". Arcadia magazine. N-Europe. 2002-05-17. Archived from the original on 2008-06-09. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ IGN Staff (2002-02-28). "Nintendo Roundtable". IGN. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2012-10-14. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- ^ "F-Zero, beyond everyone's imagination. (Interview with Toshihiro Nagoshi)". Official F-Zero GX/AX website. Archived from the original on 2006-12-24. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ "セガ、任天堂、業務用および家庭用ビデオゲームソフトウェアを共同開発". Sega. 2002-03-28. Archived from the original on 2002-06-04.

- ^ "セガ、任天堂、業務用および家庭用ビデオゲームソフトウェアを共同開発". Nintendo. 2002-03-28. Archived from the original on 2002-12-11.

- ^ Robinson, Martin (2011-04-14). "F-Zero GX: The Speed of Sega". IGN. Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-06-20.

- ^ "GameCube in 2003: Part 1". IGN. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ Wong, Erick; Degen, Matt (2003-09-05). "Fun is in devilishly good details of 'F-Zero'". The Orange County Register. p. 5.

- ^ IGN Staff (2002-03-28). "Interview: F-Zero AC/GC". IGN. Archived from the original on 2007-12-28. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ^ "Let's go to the arcade with the memory card. (Interview with Shigeru Miyamoto)". Official F-Zero GX/AX website. Archived from the original on 2008-07-13. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ "Sega and Nintendo Team Up to Bring F-Zero to Japan" (Press release). Nintendo. 2002-03-28. Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ^ a b Amusement Vision (2003-08-25). F-Zero GX (Nintendo GameCube). Sega. Scene: staff credits.

- ^ Tom, Bramwell (2003-08-08). "F-Zero GX first impressions". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

[F-Zero GX] got everything you could want, starting with an enhanced version of the Monkey Ball engine...

- ^ "Sega Shows off F-Zero". IGN. 2002-10-30. Archived from the original on 2007-07-19. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

- ^ a b c d "F-Zero GX/AX - Original Soundtracks" (in Japanese). Webcity. Archived from the original on 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ IGN Staff (2002-05-21). "E3 2002: F-Zero GCN Videos". IGN. Archived from the original on 2007-02-14. Retrieved 2006-10-19.

- ^ IGN Staff (2003-03-10). "F-Zero and Wario Delayed". IGN. Archived from the original on 2009-01-13. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ^ 騾ア刊ファミ騾8月1日号新作ゲームクロスレビューより 【今騾アの殿堂入りソフト】 (in Japanese). Famitsu. 2003-07-18. Archived from the original on 2018-10-18. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ^ "Master Game List". Nintendo. Archived from the original on 2003-08-23. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- ^ "Don't Blink & Drive...F-Zero Out Now!". Nintendo Australia. October 24, 2003. Archived from the original on December 2, 2003. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Twist, Jo (2003-08-29). "Familiar faces in Nintendo's line-up". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2012-11-10. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ^ "Game Music / F-Zero GX/AX - Original Sound Tracks". CD-Japan. Archived from the original on 2009-01-11. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- ^ a b "F-Zero GX/AX Original Soundtracks". Square Enix Music Online. Archived from the original on 2008-06-15. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

- ^ a b c "F-Zero GX reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 2013-04-29. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- ^ a b c d Ricciardi, John; Linn, Demian; Byrnes, Paul (October 2003). "F-Zero GX". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 171. Ziff Davis Media. pp. 158–159. ISSN 1058-918X. Archived from the original on 2005-01-25. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ^ a b "F-Zero GX". GameStats. Archived from the original on 2013-01-24. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ^ Keller, Matt (2003-11-01). "F-Zero GX Review". PALGN. Archived from the original on 2012-10-07. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Bozon, Mark (2007-06-28). "Wii Summertime Blues". IGN. Archived from the original on 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2007-06-29.

- ^ "IGN.com presents The Best of 2003 - Best Racing Game". IGN. Archived from the original on 2006-10-18. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ IGN staff (2003-05-22). "GameCube Best of E3 2003 Awards". IGN. Archived from the original on 2015-01-22. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ^ "GameSpot's Month in Review: August 2003". GameSpot. August 28, 2003. Archived from the original on March 1, 2004.

- ^ "Best and Worst of 2003". GameSpot. 2004-01-05. Archived from the original on 2009-02-10. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ^ "Console Racing Game of the Year". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. 2004-03-04. Archived from the original on 2022-06-30. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

- ^ East, Tom (2009-02-17). "Nintendo Feature: 100 Best Nintendo Games: Part One". Official Nintendo Magazine. Archived from the original on 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ^ EDGE presents: The 100 Best Videogames (2007). United Kingdom: Future Publishing. 16 August 2020. p. 74.

- ^ a b News & Features Team (2007-03-21). "Top 10 Tuesday: Toughest Games to Beat". IGN. Archived from the original on 2007-03-28. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ Allen, Mat. "F-Zero GX review". NTSC-uk. Archived from the original on 2022-06-12. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- ^ GT Countdown - Top Ten Most Difficult Games. GameTrailers. 2007-11-20. Event occurs at 4:19. Archived from the original on 2009-04-30. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- ^ "F-Zero GX review". 1UP.com. 2004-05-09. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2006-10-15.

- ^ "Japan GameCube charts". Famitsu. Japan Game Charts. Archived from the original on 2008-04-09. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ^ Adams, David (2004-10-14). "Fun gets cheaper in Europe". IGN. Archived from the original on 2013-10-06. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ^ IGN Staff (2004-03-16). "Mario Golf, F-Zero Go Bargain-Priced". IGN. Archived from the original on 2013-10-06. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ^ "Mortal Kombat: Deadly Alliance Goes Platinum" (Press release). Midway Games. 2003-10-06. Archived from the original on 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

The Nintendo GameCube version of Mortal Kombat: Deadly Alliance sold 250,000 units, which qualified it for the Player's Choice standard.

- ^ Brown, Nathan (October 2018). "Collected Works: Toshihiro Nagoshi". Edge. No. 323. Future plc. p. 89. Archived from the original on 2019-01-02. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

Bibliography

- Amusement Vision, ed. (2003-08-25). F-Zero GX instruction manual. Nintendo.

- F-Zero AX Deluxe Type Owner's Manual (PDF) (1st ed.). Sega Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- Mirabella III, Fran (2003-07-16). "Inside F-Zero AX". IGN. Archived from the original on 2013-10-03. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

External links

[edit]

- 2003 video games

- Amusement Vision games

- Video games about dinosaurs

- F-Zero

- GameCube-only games

- Sega arcade games

- Video games developed in Japan

- Video games produced by Shigeru Miyamoto

- Video games set on fictional planets

- Multiplayer and single-player video games

- Video games scored by Hidenori Shoji

- Video games scored by Daiki Kasho