The Schindler House, also known as the Schindler Chace House or Kings Road House, is a house in West Hollywood, California, designed by architect Rudolph M. Schindler.[2] The house serves as headquarters to the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, which operate and program three Schindler sites, and is owned and conserved by the Friends of Schindler House.

Schindler House | |

| |

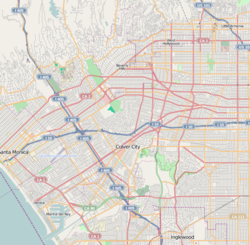

| Location | 833 N. Kings Road, West Hollywood, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°05′11″N 118°22′20″W / 34.08643°N 118.37220°W |

| Area | 1 acre (0.40 ha) |

| Built | 1922 |

| Architect | Rudolf Schindler |

| Architectural style | Modern |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000150[1] |

| Added to NRHP | July 14, 1971 |

The Schindler House was a departure from existing residential architecture because of what it did not have; there is no conventional living room, dining room or bedrooms in the house. The residence was meant to be a cooperative live/work space for two young families. The concrete walls and sliding canvas panels made novel use of industrial materials, while the open floor plan integrated the external environment into the residence, setting a precedent for California architecture in particular.

Inspiration

editSchindler and his wife Pauline vacationed[3] in Yosemite in October 1921. Inspired by the trip, Schindler returned to create a design for multiple families to share a modern living area, much like Curry Village, Yosemite National Park.[4]

Architecture

editThe Schindler House is laid out as two interlinking L-shaped apartments (referred to as the Schindler and Chace apartments) using the basic design of the camp site that he had seen a year before. Each apartment was designed for a separate family, consisting of 2 studios, connected by a utility room. The utility room was meant to serve the functions of a kitchen, laundry, sewing room, and storage. The four studios were originally designated for the four members of the household (Rudolph & Pauline Schindler and Clyde & Marian Chace). The house also has a guest studio with its own kitchen and bathroom. The house, at just under 3,500 square feet (330 m2), sits on a 20,000-square-foot (1,900 m2) lot.

Instead of bedrooms, there are two rooftop sleeping baskets. The baskets were redwood four post canopies with beams at mitered corners, protected from the rain by canvas sides.

Construction

editWhen Schindler first submitted plans to the local planning authorities, they were denied, citing this radical, at the time, new method of construction. After many trips to the local planning office and extensive talks to convince them of its merit, the Building department granted him a temporary permit, meaning that they reserved the right to halt construction at any stage.[5]

The house is built on a flat concrete slab, which is both the foundation and the final floor. The walls are concrete tilt up slabs, poured into forms on top of the foundation. The tilt up slabs are separated by 3 inches (76 mm), filled with concrete, clear glass or frosted glass. The tilt up panels act as the hard sheltering wall at the back of the house, and a softer permeable screen at the front. Schindler had long been fascinated by the construction method of tilt up concrete slabs, having done extensive research on them in his early days working for Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert. He was now intent on using this method for the new home he was designing, along with his friend Clyde Chace, an engineer and contractor who had worked closely with Irving J. Gill who pioneered tilt-up architecture in Southern California.

With Schindler as architect and Chace as builder to save costs, construction began in November 1921. Construction was complete by June 1922, with a total cost of $12,550. The landscaping, furniture and sleeping baskets remained to be completed. The Chaces and Schindlers shared the house from the summer of 1922 until July 1924 when the Chaces moved to Florida.

History

editSchindler's friend, partner and rival, Richard Neutra along with his wife Dione and son Frank lived in the Chace apartment from March 1925 until the summer of 1930.

Pauline Gibling Schindler left the house and her husband in August 1927 while Rudolph remained at the house until his death in 1953. The Chace apartment had a variety of famous and creative people live in it, including; art dealer & collector Galka Scheyer,[6] dancer John Bovingdon, novelist Theodore Dreiser, photographer Edward Weston and composer John Cage. Pauline Schindler returned to live in the Chace Studios part of the house, separate from her former husband, in the late 1930s and stayed until her death in May 1977.

Friends of the Schindler House (1977-present)

editPauline Schindler died in May 1977, leaving the house in the Schindler family until the Friends of the Schindler House (FoSH), an organization created by architects and historians passionate about the house and its legacy as well as members of the Schindler family, purchased the property in June 1980[7] from the California State Office of Historic Preservation[8] with the aid of a $160,000 state grant.[9]

FoSH owns and is responsible for the house, which was in a very challenging state when it was received. The first phase of restoration to the house was completed in the mid-1980s. By this time, the West Hollywood neighborhood had been rezoned to allow four-story apartment buildings. Gregory Ain (who greatly admired Schindler), advocated that the property should be sold and the house rebuilt in the desert, because its context had changed so profoundly.[10] As with all complex renovations, debates as to which era to return the house to have been part of the restoration and preservation process.[11]

In 2022, on the hundredth anniversary of the Schindler House, FoSH launched a campaign to stabilize and preserve the house.[12] Events during the year include special events, a film screening, and a series of online discussions of the impact of the house on architectural modernism.[13]

MAK Center for Art and Architecture (1994-present)

editOn August 10, 1994, the Friends of the Schindler House signed an agreement with the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna to create the nonprofit MAK Center for Art and Architecture.[7] The MAK Center for Art and Architecture's mission is to serve as a contemporary, experimental, multi-disciplinary center for art and architecture and is headquartered in three architectural landmarks by the Austrian-American architect Rudolph M. Schindler. The center operates a residency program and exhibition space at the Mackey Apartments (R.M. Schindler, 1939) and runs more intimate programming at the Fitzpatrick-Leland House (R.M. Schindler, 1936) in Los Angeles.

The FoSH and MAK Center agreement allow Pauline Schindler's FoSH to retain full ownership of the property, with MAK Center serving as the public-facing institution that operates the house for public visits, tours, exhibitions, programs, and events. A $250,000 grant from MAK was used to restore the house as a study center for experimental architecture, and the museum also provide significant operating costs to FoSH.[14] In 2022, the Museum der angewandte Kunst and the MAK Center contributed $150,000 in support of the FoSH's centennial campaign to restore the Schindler House.

Schindler House Centennial Celebration (2022)

editIn 2022, the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, the public institution which operates the Schindler House, presented Schindler House: 100 Years in the Making, a series of programs and exhibitions to mark the building's hundredth anniversary.[15][16]

Recognition

editSchindler's radical concept for a cooperative life/work space with its raw concrete walls and sliding canvas panels were an innovative use of industrial materials and its open floor plan thoroughly integrated the house with the surrounding gardens. "The Pit (Breitenbrunn am Neusiedlersee, Austria)", Peter Noever's land art project at the beginning of the Eurasian Steppe, situated at the interface between two world cultures, at a geopolitical intersection in the east of Austria, bares the "Concrete Fragment - Rudolph M. Schindler". A 1:1 cast of the tilt-up slabs in concrete, made on the occasion of the exhibitions at the MAK.[17][18] It is at the same time a landmark to Schindler's architectural conception, where one can clearly witness the spirit, scale and material, 6.127 miles (9.860 km) away from the Kings Road House and only 24 miles (39 km) from Schindler's birthplace.

In recent years, the Schindler House has had to contend with the rising density of the surrounding neighborhood. The surrounding neighborhood is currently dominated by 4-story condominium and apartment buildings designed by Lorcan O'Herlihy,[19] vastly different from the original expansive lots for single family residences.[20] The condominium was built despite efforts by numerous notable architects who were invited by Peter Noever on behalf of the MAK Center in 2003 to submit alternative proposals for the site. Selected by a jury that included Frank Gehry, Chris Burden, Michael Asher and Richard Koshalek,[21] all of the resulting proposals—including the three winning designs, by Odile Decq, Eric Owen Moss and Carl Pruscha—were organized into an exhibition, "A Tribute to Preserving Schindler's Paradise," at the house.[19] Other competition entrants included Coop Himmelb(l)au, Lebbeus Woods, Dominique Perrault, Zaha Hadid, and Peter Eisenman.[22] All submitted projects are documented in the publication "ARCHITECTURAL RESISTANCE."[23]

The Schindler House was included in a list of all-time top 10 houses in Los Angeles in a Los Angeles Times survey of experts in December 2008.[24]

-

Architectural drawings and elevations

(click to see the rest of the sheets) -

Schindler House exterior from Kings Road

-

Robert Sweeney, Harriett Gold and Peter Noever, signing of corporation agreement between Friends of the Schindler House (FOSH) and the Republic of Austria, August 10, 1994, West Hollywood

Notes

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Kathryn; Grant Mudford (2001). Schindler House. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. pp. 7–40. ISBN 0-8109-2985-6.

- ^ Charlie Hailey - 2008 - Campsite: Architectures of Duration and Place

- ^ Miranda, Carolina A. (June 15, 2022). "As the Schindler House turns 100, a new exhibition reexamines its complex legacy". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ McCoy, Esther (1960). Five California Architects. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation. ASIN B000I3Z52W.

- ^ Scheyer was the American representative of the Blue Four (painters Wassily Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlensky, Paul Klee & Lyonel Feininger).

- ^ a b Noever, Peter (2005). Schindler by MAK: Prestel Museum Guide. Prestel Verlag. ISBN 3-7913-2837-9.

- ^ Suzanne Muchnic (February 18, 1996), Preserving Schindler's L.A. Legacy: The historic buildings of modernist architect Rudolf M. Schindler are getting a sprucing up--thanks to his native Austria Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Leon Whiteson (October 1, 1989), Schindler Ode to Modernism on the Mend Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Denzer, Anthony (2008). Gregory Ain: The Modern Home as Social Commentary. Rizzoli Publications. ISBN 978-0-8478-3062-6. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ Giovannini, Joseph (December 3, 1987). "A Modernist Architect's Home Is Restored in Los Angeles". New York Times.

- ^ "100 years". the SCHINDLER HOUSE. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "Celebrating the Centennial of (Arguably) the World's First Modern House, in West Hollywood". The New Yorker. July 21, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ Irene Lacher (August 18, 1994), Rescuing a Design Icon: An Austrian museum provides funds to restore the Schindler House Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Schindler House: 100 Years in the Making. 29 May.-25 Sept. 2022, MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

- ^ "As the Schindler House turns 100, a new exhibition reexamines its complex legacy". Los Angeles Times. June 15, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ Vienna "R. M. Schindler - Architektur und Experiment", 2001 and "R. M. Schindler, Architekt", 1986.

- ^ "R. M. Schindle - Architektur und Experiment". OTS.at (in German). Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Diane Haithman (December 7, 2003). "Builder, architects have designs on Kings Road". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Hawthorne, Christopher (September 5, 2007). "Habitat 825 is so close and yet so far". Los Angeles Times. pp. E1 & E10.

- ^ Louise Roug (June 29, 2003). "Land parcel becomes a blank canvas". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Louise Roug (August 8, 2003). "A spirit of resistance builds". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Noever, Peter (2003). ARCHITECTURAL RESISTANCE. hatje cantz. ISBN 3-7757-1406-5.

- ^ Mitchell, Sean (December 27, 2008). "The best houses of all time in L.A." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 27, 2008.