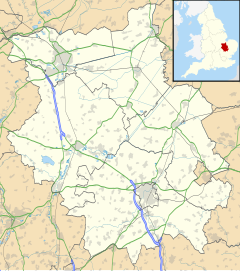

Little Gidding is a small village and civil parish in Cambridgeshire, England.[2] It lies approximately 9 miles (14 km) northwest of Huntingdon, near Sawtry, within Huntingdonshire, which is a district of Cambridgeshire as well as a historic county.

| Little Gidding | |

|---|---|

Location within Cambridgeshire | |

| Population | 362 (with Great Gidding and Steeple Gidding)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TL131819 |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | HUNTINGDON |

| Postcode district | PE28 |

| Dialling code | 01832 |

| Police | Cambridgeshire |

| Fire | Cambridgeshire |

| Ambulance | East of England |

A small parish of 724 acres (293 hectares), Little Gidding recorded a population of 22 in the 1991 British Census. With the neighbouring villages of Great Gidding (where the population was in 2011 included) and Steeple Gidding, the total population was 362 in 2001.[1] The driving distance between Little Gidding and Cambridge, to the southeast, is 30 miles.

St John's Church, the Church of England parish church, is a Grade I listed building.[4][5]

Little Gidding was the home of a small Anglican religious community established in 1626 by Nicholas Ferrar, two of his siblings and their extended families. It was founded around strict adherence to Christian worship in accordance with the Book of Common Prayer and the High Church heritage of the Church of England. Charles I visited Little Gidding three times. The community continued for 20 years after Ferrar's death, until after the deaths of his brother and sister in 1657.

In the 20th century, the poet T. S. Eliot (1888–1965) was inspired by the legacy of the religious community at Little Gidding. He incorporated historical elements and symbols of it into his long poem, "Little Gidding", as part of his collection Four Quartets (1945).

History

editEarly history

editAt the time of the Domesday Book, the only entry for this area was Geddinge, indicating that the three parishes of Little Gidding, Great Gidding and Steeple Gidding were separated later. Gidding, then owned by William Engaine, passed to his grandson, who gave Little Gidding to his younger son, Warner Engaine, in around 1166. At that time the manor was known as Gidding Warner, later becoming Gidding Engaine and by the 13th century Gydding Parva or Little Gidding.[6][7]

The name Gidding means "settlement of the family or followers of a man called Gydda".[8] Little Gidding is notable as the home of a Church of England lay religious community established by the Ferrar family in 1626.

Nicholas Ferrar's community

editIn 1620, Esmé Stewart, Earl of March sold the manor of Little Gidding to Thomas Sheppard. Population had declined in this rural area. Sheppard then sold the property to Nicholas Ferrar (1592–1637) and his cousin Arthur Wodenoth (or Woodnoth) (1590?–1650?) in 1625 as trustees for Ferrar's mother, Mary Ferrar (née Wodenoth). The Ferrars and Wodenoths were investors in the Virginia Company[9] and other colonial projects.

With the collapse of the Virginia Company and the loss of a large portion of their fortune, the Ferrar family retreated to Little Gidding to take on a spiritual life of prayer, eschewing the world. The following year, in 1626, Nicholas Ferrar was ordained as a deacon by William Laud, then Bishop of St David's and later Archbishop of Canterbury.[10]

The extended Ferrar family transformed the holdings at Little Gidding into a religious community. When they purchased it, the property consisted of a decayed manor house and the village's medieval parish church of St John. The Ferrars began repairing the site.[10] Nicholas Ferrar was joined by his brother John Ferrar and his family, and their sister Susanna (Ferrar) Collett and her family. The community was never a formal religious community, and had no official Rule: no vows were required, and no enclosure. The Ferrar household lived a Christian life according to High Church principles and the Book of Common Prayer. They looked to the health and education of local children, and engaged in bookbinding.

The Ferrar household attracted visitors: Richard Crashaw came a number of times, and was on good terms with Mary Collet.[11] When the matriarch Mary Ferrar died in 1634, Little Gidding passed to her son Nicholas.[6] In December 1637 he died, but the community continued under the leadership of his brother, John Ferrar, until 1657, when he and his sister Susanna Collett died within a month of each other.[12]

The Little Gidding settlement was also criticised by Puritans, denounced as a "Protestant Nunnery" of Arminian heretics; in 1641 it was attacked in a pamphlet entitled "The Arminian Nunnery". The pamphlet was anonymous, but drew on a written account of a visit in 1634 by the barrister Edward Lenton.[13]

Mark Frank made contact with Little Gidding after the parliamentary visitation of the University of Cambridge of 1643.[14] During a period of local unrest in the Civil War, John Ferrar and some of his family went to Holland, but they returned by 1646.[15] There have been claims about ransacking of the church and the estate during the Civil War but recent research disproves those.[15][16] King Charles I visited three times, the last occasion being on 2 May 1646, seeking refuge after the Royalist defeat at the Battle of Naseby. He was given temporary refuge by John Ferrar.[17] That year the religious community was closed down.[14]

Bishop Francis Turner (1637–1700) composed a memoir of Nicholas Ferrar.[18]

Later Anglican life at Little Gidding

editWilliam Hopkinson bought the 700 acres estate in 1848 and became Lord of the Manor of Little Gidding;[19] he is buried in the graveyard. His heir was the Rev. William Hopkinson, his nephew, from 1865 to 1873 vicar of Great Gidding.[20]

With the Oxford Movement and the revival of Anglican religious orders, Little Gidding and its Ferrar household were "much idealized by nineteenth-century Anglo-Catholics".[21] It featured prominently in the 1881 historical novel John Inglesant by Joseph Henry Shorthouse. According to ascetical theologian Martin Thornton, Nicholas Ferrar and the Little Gidding community exemplified an appeal based in a lack of rigidity (representing the best Anglicanism's via media can offer) and "common-sense simplicity" coupled with "pastoral warmth" related to Christian origins.[22]

The Friends of Little Gidding was founded in 1946 by Alan Maycock, with support from T. S. Eliot, to maintain and adorn the church, and to honour the life of Nicholas Ferrar and his family and their life at Little Gidding. Inspired by the example of Ferrar, the Community of Christ the Sower was founded at Little Gidding in the 1970s but that community ended in 1998.

Government

editGreat and Little Gidding together have a parish council, the lowest tier of government in England.

Little Gidding was in the historic administrative county of Huntingdonshire. From 1965, the parish was part of the new administrative county of Huntingdon and Peterborough and, in 1974, following the Local Government Act 1972, of Cambridgeshire.

The second tier of local government is Huntingdonshire District Council which is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire. The District Council has 52 councillors representing 29 district wards.[23] Little Gidding is a part of the ward of Sawtry represented on the district council by two councillors.[24][23] District councillors serve for four year terms following elections to Huntingdonshire District Council.

For Little Gidding the highest tier of local government is Cambridgeshire County Council. The County Council consists of 69 councillors representing 60 electoral divisions.[25] Little Gidding is part of the division of Sawtry and Ellington[24] represented by one county councillor.[25]

Little Gidding is in the parliamentary constituency of North West Cambridgeshire.[24] It is represented in the House of Commons by Shailesh Vara (Conservative).

Demography

editPopulation

editIn the period 1801 to 1901 the population of Little Gidding was recorded every ten years by the UK census. During this time the population was in the range of 39 (the lowest was in 1901) and 70 (the highest was in 1811).[26]

From 1901, a census was taken every ten years with the exception of 1941 (due to the Second World War).

| Parish |

1911 |

1921 |

1931 |

1951 |

1961 |

1971 |

1981 |

1991 |

2001 |

2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little Gidding | 48 | 42 | 42 | 28 | 31 | 17 | 27 | 22 | 25 | 25 |

All population census figures from report Historic Census figures Cambridgeshire to 2011 by Cambridgeshire Insight.[26]

In 2011, the parish covered an area of 724 acres (293 hectares)[26] and the population density of Little Gidding in 2011 was 22.1 persons per square mile (8.5 per square kilometre). From the 2011 Census the population was included in the civil parish of Great Gidding.

Culture and community

editT. S. Eliot and Four Quartets

editThe legacy of the Anglican community at Little Gidding inspired American-English poet, T. S. Eliot (1888–1965) in his poem entitled Little Gidding, the final of four long poems that compose the collection Four Quartets (1945). Eliot, a convert to Anglicanism who identified as an Anglo-Catholic and was a life member of the Society of King Charles the Martyr,[27][28] visited Little Gidding church on 25 May 1936. This was six years before he published his poem.[29] Eliot, a noted critic, supposedly had been asked to read a play regarding Charles I visiting the community.[30]

In the poem named after this site, Eliot combined the image of fire and Pentecostal fire to emphasise the need for purification and purgation, saying humanity's flawed understanding of life and turning away from God leads to a cycle of warfare. Eliot intends to portray this suffering as restorative — that it was necessary to experience catastrophic pain before life can be renewed and begin anew. Humanity's errors in thought that led to this suffering can be overcome by recognizing the lessons of the past and focusing on the unity of past, present, and future — a unity that Eliot asserts is necessary for salvation.[31] Eliot draws imagery from the history of the Little Gidding community and its role in the Civil War and the fall of Charles I (whom Eliot calls the "broken King"), relating this past to a present in which Britain was struggling with the devastation of The Blitz during World War II.

Annual events

editDuring the summer a Little Gidding Pilgrimage is held, sponsored by the Friends of Little Gidding. The format in recent years has been Holy Communion at Leighton Bromswold, followed by dinner. Then the pilgrims walk the five miles to Little Gidding. Along the way, there are rest stops where prayers and meditation occur. Upon reaching Nicholas Ferrar's grave, prayers are offered followed by Choral Evensong in St John's parish church.[32]

On the Saturday closest to the anniversary of Nicholas Ferrar's death on 4 December 1637, a commemorative service is held at St John's Church. The Friends of Little Gidding hold their Annual General Meeting at that time.[33]

An annual T. S. Eliot Festival is organised by the Friends of Little Gidding and the T. S. Eliot Society.[34]

See also

edit- Henry William Pullen (born at Little Gidding in 1836), clergyman and writer

References

edit- ^ a b Cambridge County Council Research Group. 2001 Census Profile: Great Gidding, Little Gidding and Steeple Gidding Parishes – Huntingtdonshire Archived 18 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine from 2001 Census Key Statistics for Local Authorities (Published: October 2003). Retrieved 5 January 2013. Note: These three parishes are combined because one of them, Little Gidding, is too small to be enumerated separately in accordance with British privacy laws.

- ^ Ordnance Survey: Landranger map sheet 142 Peterborough (Market Deeping & Chatteris) (Map). Ordnance Survey. 2012. ISBN 9780319229248.

- ^ Skipton, Horace Pott Kennedy (1907). The Life and Times of Nicholas Ferrar. London: A. R. Mowbray. p. 136.

- ^ "Parish Church of St John the Evangelist, Little Gidding". Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Historic England. "Parish Church of St John the Evangelist (1130115)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ a b A History of the County of Huntingdon (Victoria County History, 1936) III:53–57

- ^ White, J.M. (22 March 2017). "Polychromatic Mysticism: A Visit to Little Gidding, by J. M. White". Parabola.

- ^ A. D. Mills (2003). "A Dictionary of British Place-Names".[dead link]

- ^ Lee, Sidney, ed. (1900). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 62. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ a b "A brief history of Little Gidding" (The Official Website of St John's Church, Little Gidding, Cambridgeshire, England). Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ Healy, Thomas. "Crashaw, Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6622. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ A History of the County of Huntingdon. Vol. 1. Victoria County History. 1926. pp. 399–406.

- ^ West, Philip. "Little Gidding community (act. 1626–1657)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68969. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Stevenson, Kenneth W. "Frank, Mark". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10082. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Alleged Ransacking of Little Gidding Church 1646

- ^ Riley, Kate E. (2007). The Good Old Way Revisited: The Ferrar Family of Little Gidding, c. 1625–1637 (Ph.D.). The University of Western Australia.

- ^ Peckard, Peter (1790). Memoirs of the Life of Nicholas Ferrar. Cambridge: Printed by J. Archdeacon.

- ^ Ferrar, Nicholas (1837). Turner, Francis; MacDonogh, The Revd Terence Michael (eds.). Brief memoirs of Nicholas Ferrar: founder of a Protestant religious establishment at Little Gidding, Huntingdonshire. London: Jas Nisbet.

- ^ "++ Little Gidding Church – William Hopkinson ++". www.littlegiddingchurch.org.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ "Hopkinson, William (HPKN859W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Kilburn, Matthew. "Gibbs, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/89656. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Thornton, Martin (1963). English spirituality: an outline of ascetical theology according to the English pastoral tradition. S.P.C.K. pp. 46–47, 116, 226.

- ^ a b "Huntingdonshire District Council: Councillors". www.huntingdonshire.gov.uk. Huntingdonshire District Council. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "Ordnance Survey Election Maps". www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk. Ordnance Survey. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Cambridgeshire County Council: Councillors". www.cambridgeshire.gov.uk. Cambridgeshire County Council. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "Historic Census figures Cambridgeshire to 2011". www.cambridgeshireinsight.org.uk. Cambridgeshire Insight. Archived from the original (xlsx – download) on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Plaque on interior wall of Saint Stephen's, Gloucester Road, London.

- ^ Obituary notice in Church and King, Vol. XVII, No. 4, 28 February 1965, p. 3.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter. T.S. Eliot: A Life. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984), 263–266.

- ^ T.S. Eliot and Little Gidding – The Friends of Little Gidding (official website). Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ Pinion, F. B. A T. S. Eliot Companion (London: MacMillan, 1986), pp. 229–34.

- ^ The 2013 Little Gidding Pilgrimage

- ^ 2012 Nicholas Ferrar Day

- ^ T. S. Eliot and Little Gidding

Further reading

edit- Acland, John Edward. Little Gidding and Its Inmates in the Time of King Charles I. with an Account of the Harmonies – via Project Gutenberg.

- Counsell, Michael (2003). Every Pilgrim's Guide to England's Holy Places. Hymns Ancient and Modern. pp. 190–. ISBN 978-1-85311-522-6.

- William Page; Granville Proby; S Inskip Ladds, eds. (1936). "Parishes: Little Gidding". A History of the County of Huntingdon. Vol. 3. London. pp. 53–57. Retrieved 17 November 2017 – via British History Online.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cranage, DHS (1928). "An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Huntingdonshire (Royal Commission on Historical Monuments)". The English Historical Review. 43 (170). Oxford University Press: 281–282. doi:10.1093/ehr/xliii.clxx.281. JSTOR 552027.

- Ferrar, Nicholas (1837). Turner, Francis; MacDonogh, The Revd Terence Michael (eds.). Brief memoirs of Nicholas Ferrar: founder of a Protestant religious establishment at Little Gidding, Huntingdonshire. London: Jas Nisbet.

- Maycock, Alan Lawson (1954). Chronicles of Little Gidding. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Maycock, Alan Lawson (1963). Nicholas Ferrar of Little Gidding. S.P.C.K.

- Ferrar, Nicholas (2 November 2006). Conversations at Little Gidding. Cambridge University Press. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-0-521-02821-9.

- Moore, William W. (1993). The Little Church that Refused to Die. Allison Park, PA: Pickwick Publications.

- Ransome, Joyce (2011). The Web of Friendship: Nicholas Ferrar and Little Gidding. Cambridge: James Clarke. ISBN 978-0-227-90090-1.

- Riley, Kate E. (2007). The Good Old Way Revisited: The Ferrar Family of Little Gidding, c. 1625–1637 (Ph.D.). The University of Western Australia.

- An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Huntingdonshire, Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England), London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1926, pp. xliii, 350 p. : ill. (incl. plans), plates, maps, 28 cm. 'Gidding, Little', pp. 101–102 and illustrations throughout the book, retrieved 17 November 2017 – via British History Online,

David Lindsay, 27th Earl of Crawford was chairman of this commission

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Skipton, Horace Pott Kennedy (1907). The Life and Times of Nicholas Ferrar. London: A. R. Mowbray.

- Hodgson, Tony (2010). Little Gidding Then and Now. Spirituality Series. Grove.

External links

edit- Alleged Ransacking of Little Gidding Church 1646

- A brief history of Little Gidding (The official website of St John's Church, Little Gidding) Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Ferrar House, a retreat centre located in Little Gidding

- Friends of Little Gidding

- The Giddings, the website for the villages of Great Gidding, Little Gidding and Steeple Gidding

- Little Gidding, Cambridgeshire from a blog by James P. Miller (with photographs)

- St John's Church, Little Gidding

- Small Pilgrim Places Network; Little Gidding

- Records of St John the Evangelist, Little Gidding. Inventory of materials at the Cambridgeshire County Record Office, Huntingdon, United Kingdom

- Little Gidding Harmonies produced by the Ferrars

- Little Gidding–St John's Church on YouTube

- A Visit to Little Gidding on YouTube

- Extracts from 'Little Gidding' - the poem by T S Eliot - read in Little Gidding on YouTube