Franklin Patrick Herbert Jr. (October 8, 1920 – February 11, 1986) was an American science-fiction author, best known for his 1965 novel Dune and its five sequels. He also wrote short stories and worked as a newspaper journalist, photographer, book reviewer, ecological consultant, and lecturer.

Frank Herbert | |

|---|---|

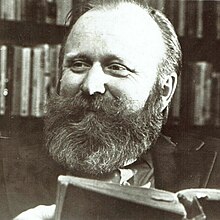

Herbert in 1984 | |

| Born | Franklin Patrick Herbert Jr. October 8, 1920 Tacoma, Washington, U.S. |

| Died | February 11, 1986 (aged 65) Madison, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Education | University of Washington (no degree) |

| Period | 1945–1986 |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Literary movement | New Wave |

| Notable works | Dune |

| Notable awards | Hugo Award for Best Novel

Nebula Award for Best Novel

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3, including Brian Herbert |

| Signature | |

Dune is the best-selling science fiction novel of all time,[3] and the series is a classic of the science-fiction genre.[4] The Dune saga, set in the distant future and taking place over millennia, explores complex themes, such as the long-term survival of the human species, human evolution, planetary science and ecology, and the intersection of religion, politics, economics, sex, and power in a future where humanity has long since developed interstellar travel and colonized many thousands of worlds.

The series has been adapted numerous times, including the feature film Dune (1984), the miniseries Frank Herbert's Dune and Children of Dune, and a motion picture trilogy currently in production, with Dune (2021) and Dune: Part Two (2024) having been released.[5][6]

Biography

editEarly life

editFrank Patrick Herbert Jr. was born on October 8, 1920, in Tacoma, Washington,[7][8] to Frank Patrick Herbert Sr. and Eileen (née McCarthy) Herbert.[9] His paternal grandparents had come west in 1905 to join Burley Colony in Kitsap County, one of many utopian communes springing up in Washington State beginning in the 1890s.[10] His upbringing included spending a lot of time on the rural Olympic and Kitsap Peninsulas.[11] He was fascinated by books, could read much of the newspaper before the age of five, had an excellent memory, and learned quickly.[12] He had an early interest in photography, buying a Kodak box camera at age ten, a new folding camera in his early teens, and a color film camera in the mid-1930s.[12] Due to his parents' drinking, he ran away from home with his little sister, 5-year-old Patricia Lou, in 1938 to live with Frank's favorite maternal aunt, Peggy "Violet" Rowntree, and her husband, Ken Rowntree, Sr.[13] Within weeks, Patricia moved back home. But Frank, 18, remained with his aunt and uncle.

Education

editHe enrolled in high school at Salem High School (now North Salem High School), where he graduated the next year.[13] In 1939, his parents and sister had moved to Los Angeles, California, so Frank followed them. He lied about his age to get his first newspaper job at the Glendale Star.[14] Herbert then returned to Salem in 1940 where he worked for the Oregon Statesman newspaper (now Statesman Journal) in a variety of positions, including photographer.[13]

Herbert married Flora Lillian Parkinson in San Pedro, California, in 1941. They had one daughter, Penelope (b. February 16, 1942), and divorced in 1943.[1] During 1942, after the U.S. entry into World War II, he served in the U.S. Navy's Seabees for six months as a photographer, but suffered a head injury and was given a medical discharge. Herbert subsequently moved to Portland, Oregon where he reported for The Oregon Journal.[15]

After the war, Herbert attended the University of Washington, where he met Beverly Ann Stuart at a creative writing class in 1946. They were the only students who had sold any work for publication; Herbert had sold two pulp adventure stories to magazines, the first to Esquire in 1945 titled "Survival of the Cunning", and Stuart had sold a story to Modern Romance magazine. They married in Seattle in 1946, and had two sons, Brian (b. 1947) and Bruce (1951–1993).[16][17] In 1949 Herbert and his wife moved to California to work on the Santa Rosa Press-Democrat. Here they befriended the psychologists Ralph and Irene Slattery. The Slatterys introduced Herbert to the work of several thinkers who would influence his writing, including Freud, Jung, Jaspers and Heidegger; they also familiarized Herbert with Zen Buddhism.[18]

Herbert never graduated from college. According to his son Brian, he wanted to study only what interested him and so did not complete the required curriculum. He returned to journalism and worked at the Seattle Star and the Oregon Statesman. He was a writer and editor for the San Francisco Examiner's California Living magazine for a decade.

Early career

editIn a 1973 interview, Herbert stated that he had been reading science fiction "about ten years" before he began writing in the genre, and he listed his favorite authors as H. G. Wells, Robert A. Heinlein, Poul Anderson and Jack Vance.[19]

Herbert's first science fiction story, "Looking for Something", was published in the April 1952 issue of Startling Stories, then a monthly edited by Samuel Mines. Three more of his stories appeared in 1954 issues of Astounding Science Fiction and Amazing Stories.[20] His career as a novelist began in 1955 with the serial publication of Under Pressure in Astounding from November 1955; afterward it was issued as a book by Doubleday titled The Dragon in the Sea.[20] The story explored sanity and madness in the environment of a 21st-century submarine and predicted worldwide conflicts over oil consumption and production.[21] It was a critical success but not a major commercial one. During this time Herbert also worked as a speechwriter for Republican senator Guy Cordon.[22]

Dune

editHerbert began researching Dune in 1959.[23] He was able to devote himself wholeheartedly to his writing career because his wife returned to work full-time as an advertising writer for department stores, becoming their breadwinner during the 1960s.[24] The novel Dune was published in 1965, which spearheaded the Dune franchise.[25] He later told Willis E. McNelly that the novel originated when he was assigned to write a magazine article about sand dunes in the Oregon Dunes near Florence, Oregon.[26] He got overinvolved and ended up with far more raw material than needed for an article; while the article was never written, it planted in Herbert the seed that would become Dune.[27] Another possible source of inspiration for Dune was Herbert's purported experiences with psilocybin, according to mycologist Paul Stamets's account, which describes Herbert's hobby of cultivating chanterelles.[28] The biography of Frank Herbert, Dreamer of Dune, written by his son Brian Herbert, confirms that the author was passionate about culinary mushrooms but not his use of psilocybin.[12]

Dune took six years of research and writing to complete and was much longer than other commercial science fiction of the time.[29] Analog (the renamed Astounding, still edited by John W. Campbell) published it in two parts comprising eight installments, "Dune World" from December 1963 and "Prophet of Dune" in 1965.[20] It was then rejected by nearly twenty book publishers.[citation needed] One editor prophetically wrote, "I might be making the mistake of the decade, but..."[30]

Sterling E. Lanier, an editor of Chilton Book Company (known mainly for its auto-repair manuals), had read the Dune serials and offered a $7,500 advance plus future royalties for the rights to publish them as a hardcover book.[31] Herbert rewrote much of his text.[32]

Dune was soon a critical success.[30] It won the Nebula Award for Best Novel in 1965 and shared the Hugo Award in 1966 with ...And Call Me Conrad by Roger Zelazny.[33]

Dune was not an immediate bestseller, although by 1968 Herbert had made $20,000 from it, far more than most science fiction novels of the time.[34] It was not, however, enough to let him take up full-time writing.[35] The publication of Dune did open doors for him; he was the Seattle Post-Intelligencer's education writer from 1969 to 1972 and lecturer in general studies and interdisciplinary studies at the University of Washington (1970–1972).[citation needed] He worked in Vietnam and Pakistan as a social and ecological consultant in 1972, and in 1973 he was director-photographer of the television show The Tillers.[36]

I don't worry about inspiration or anything like that.... later, coming back and reading what I have produced, I am unable to detect the difference between what came easily and when I had to sit down and say, "Well, now it's writing time and now I'll write."[37]

— Frank Herbert

By the end of 1972, Herbert had retired from newspaper writing and became a full-time fiction writer. During the 1970s and 1980s, he enjoyed considerable commercial success as an author. He divided his time between homes in Hawaii and Washington's Olympic Peninsula; his home in Port Townsend on the peninsula was intended to be an "ecological demonstration project".[38][page needed] During this time he wrote numerous books and pushed ecological and philosophical ideas. He continued his Dune saga with Dune Messiah (1969), Children of Dune (1976), God Emperor of Dune (1981), Heretics of Dune (1984) and Chapterhouse: Dune (1985). Herbert planned to write a seventh novel to conclude the series, but his death in 1986 left storylines unresolved.[39]

Other works by Herbert include The Godmakers (1972), The Dosadi Experiment (1977), The White Plague (1982) and the books he wrote in partnership with Bill Ransom: The Jesus Incident (1979), The Lazarus Effect (1983) and The Ascension Factor (1988), which were sequels to Herbert's 1966 novel Destination: Void. He also helped launch the career of Terry Brooks with a very positive review of Brooks' first novel, The Sword of Shannara, in 1977.[40]

Success, family changes, and death

editHerbert's change in fortune was shadowed by tragedy. In 1974, his wife Beverly underwent treatment for lung cancer. She lived ten more years, but her health was adversely affected by the treatment.[41] In October 1978, Herbert was the featured speaker at the Octocon II science fiction convention held at the El Rancho Tropicana in Santa Rosa, California.[42] In 1979, he met anthropologist Jim Funaro with whom he conceived the Contact Conference.[43] Beverly Herbert died on February 7, 1984.[2] Herbert completed and published Heretics of Dune that year. In his afterword to 1985's Chapterhouse: Dune, Herbert included a dedication to Beverly.

The year 1984 was a tumultuous year in Herbert's life. During this same year of his wife's death, his career took off with the release of David Lynch's film version of Dune. Despite high expectations, a big-budget production design and an A-list cast, the movie drew mostly poor reviews in the United States. However, despite a disappointing response in the US, the film was a critical and commercial success in Europe and Japan.[32]

In 1985, after Beverly's death, Herbert married his former Putnam representative Theresa Shackleford.[44] The same year he published Chapterhouse: Dune, which tied up many of the saga's story threads. This would be Herbert's final single work (the collection Eye was published that year, and Man of Two Worlds was published in 1986). He died of a massive pulmonary embolism while recovering from surgery for pancreatic cancer on February 11, 1986, in Madison, Wisconsin, aged 65.[38][45]

Political views

editHerbert was a Republican[46] and an environmentalist.[47] His political views have been variously described as conservative,[46] reactionist,[48] and libertarian.[49] Herbert was politically active within the Republican party, and worked as a speechwriter for several politicians, including Senator Guy Cordon. Herbert also volunteered on the campaign of Republican William Blintz in the 1958 Washington Senate election, who unsuccessfully challenged the incumbent Democrat Henry M. Jackson.[50]

Herbert was a critic of the Soviet Union. He was a distant relative of the Republican senator Joseph McCarthy, whom he referred to as "Cousin Joe". However, he was appalled to learn of McCarthy's blacklisting of suspected communists from working in certain careers and believed that he was endangering essential freedoms of citizens of the United States.[51] Herbert also opposed American involvement in the war in Vietnam.[52] He was also critical of welfare, arguing that it increased dependence on the state.[46]

Herbert believed that governments lie to protect themselves and that, following the Watergate scandal, President Richard Nixon had unwittingly taught an important lesson in not trusting government.[53][54] He considered Nixon a better president than John F. Kennedy, calling the latter "one of the most dangerous presidents this country ever had."[55] He praised President Ronald Reagan, for his pro-family and pro-individualist stances, while opposing his foreign policy.[46]

In Chapterhouse: Dune, he wrote:

All governments suffer a recurring problem: Power attracts pathological personalities. It is not that power corrupts but that it is magnetic to the corruptible. Such people have a tendency to become drunk on violence, a condition to which they are quickly addicted.

— Frank Herbert, Chapterhouse: Dune[41]: 59

Frank Herbert believed civil service to be "one of the most serious errors we made as a democracy" and that bureaucracy negatively impacts the lives of people in all forms of government. He stated that "every such bureaucracy eventually becomes an aristocracy" and uses preferential treatment and nepotism in favor of bureaucrats as his main arguments.[56]

Ideas and themes

editFrank Herbert used his science fiction novels to explore complex[57] ideas involving philosophy, religion, psychology, politics and ecology. The underlying thrust of his work was a fascination with the question of human survival and evolution. Herbert has attracted a dedicated fan base, many of whom have attempted to read everything he wrote (fiction or non-fiction); indeed, such was the devotion of some of his readers that Herbert was at times asked if he was founding a cult,[58] a proposition which he very much rejected.

There are a number of key themes found in Herbert's work:

- A concern with leadership: Herbert explored the human tendency to slavishly submit itself to charismatic leaders. He delved into both the flaws and potentials of bureaucracy and government.[21]

- Herbert was among the first science fiction authors to popularize ideas about ecology[59] and systems thinking. He stressed the need for humans to think both holistically and with regards to the long-term.[60]

- The relationship between religion, politics and power.[61]

- Human survival and evolution: Herbert writes of the Fremen, the Sardaukar, and the Dosadi, who are molded by their terrible living conditions into dangerous super races.[62]

- Human possibilities and potential: Herbert offered Mentats, the Bene Gesserit and the Bene Tleilax as different visions of human potential.

- The nature of sanity and madness. Frank Herbert was interested in the work of Thomas Szasz and the anti-psychiatry movement. Often, Herbert poses the question, "What is sane?", and while there are clearly examples of insane behavior and psychopathy to be found in his works (as evinced by characters such as Piter De Vries), it is often suggested that normal and abnormal are relative terms which humans are sometimes ill-equipped to apply to one another, especially on the basis of statistical regularity.[21]

- The possible effects and consequences of consciousness-altering chemicals, such as the spice in the Dune saga, as well as the 'Jaspers' fungus in The Santaroga Barrier, and the Kelp in the Destination: Void sequence.[21]

- How language shapes thought. More specifically, Herbert was influenced by Alfred Korzybski's General Semantics.[63] Algis Budrys wrote that Herbert's knowledge of language and linguistics was 'worth at least one PhD and the Chair of Philology at a good New England college'.[64]

- Learning, teaching, and thinking.[21]

Frank Herbert refrained from offering his readers formulaic answers to many of the questions he explored.[21]

Status and influence on science fiction

editDune and the Dune saga constitute one of the world's best-selling science fiction series and novels; Dune in particular has received widespread critical acclaim, winning the Nebula Award in 1965 and sharing the Hugo Award in 1966, and is frequently considered one of the best science fiction novels ever, if not the best.[65] Locus subscribers voted it the all-time best SF novel in 1975, again in 1987, and the best "before 1990" in 1998.[66]

Dune is considered a landmark novel for a number of reasons:

- Dune is a landmark of soft science fiction. Herbert deliberately suppressed technology in his Dune universe so that he could address the future of humanity, rather than the future of humanity's technology. Dune considers the way humans and their institutions might change over time.[67][68]

- Frank Herbert was a great popularizer of scientific ideas. In Dune, he helped popularize the term ecology. Gerald Jonas explains in The New York Times Book Review: "So completely did Mr. Herbert work out the interactions of man and beast and geography and climate that Dune became the standard for an emerging subgenre of 'ecological' science fiction."

- Dune is considered an example of literary world-building. The Library Journal reports that "Dune is to science fiction what The Lord of the Rings is to fantasy". Arthur C. Clarke is quoted as making a similar statement on the back cover of a paper edition of Dune.[69] Frank Herbert imagined every facet of his creation. He included glossaries, quotes, documents, and histories, to bring his universe alive to his readers. No science fiction novel before it had so vividly realized life on another world.[21]

Herbert never again equalled the critical acclaim he received for Dune. Neither his sequels to Dune nor any of his other books won a Hugo or Nebula Award, although almost all of them were New York Times Best Sellers.[70]

Malcolm Edwards wrote, in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction:[71]

Much of Herbert's work makes difficult reading. His ideas were genuinely developed concepts, not merely decorative notions, but they were sometimes embodied in excessively complicated plots and articulated in prose which did not always match the level of thinking [...] His best novels, however, were the work of a speculative intellect with few rivals in modern science fiction.

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame inducted Herbert in 2006.[70][72][73]

California State University, Fullerton's Pollack Library has several of Herbert's draft manuscripts of Dune and other works, with the author's notes, in their Frank Herbert Archives.[74]

Metro Parks Tacoma built Dune Peninsula and the Frank Herbert Trail at Point Defiance Park in July 2019 to honor the hometown writer.[75]

Bibliography

editPosthumously published works

editBeginning in 2012, Herbert's estate and WordFire Press have released four previously unpublished novels in e-book and paperback formats: High-Opp (2012),[76] Angels' Fall (2013),[77] A Game of Authors (2013),[78] and A Thorn in the Bush (2014).[79]

In recent years, Frank Herbert's son Brian Herbert and author Kevin J. Anderson have added to the Dune franchise, using notes left behind by Frank Herbert and discovered over a decade after his death. Brian Herbert and Anderson have written three prequel trilogies (Prelude to Dune, Legends of Dune and Great Schools of Dune) exploring the history of the Dune universe before the events of the original novel, two novels that take place between novels of the original Dune sequels (with plans for more), as well as two post-Chapterhouse Dune novels that complete the original series (Hunters of Dune and Sandworms of Dune) based on Frank Herbert's own Dune 7 outline.[80][81][82]

References

edit- ^ a b Oregon Center For Health Statistics; Portland, Oregon, US; Oregon, Divorce Records, 1925–1945; Document no. 30939

- ^ a b Washington State Archives; Olympia, Washington; Washington Death Index, 1940–1959, 1965–2017; Certificate no. 090281.

- ^ "SCI FI Channel Auction to Benefit Reading Is Fundamental". PNNonline.org (Internet Archive). March 18, 2003. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

Since its debut in 1965, Frank Herbert's Dune has sold over 12 million copies worldwide, making it the best-selling science fiction novel of all time [...] Frank Herbert's Dune saga is one of the greatest 20th Century contributions to literature.

- ^ Kunzru, Hari (July 3, 2015). "Dune, 50 years on: how a science fiction novel changed the world". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "Denis Villeneuve's 'Dune' Will Probably Finish Its Story — But There's a Catch". Inverse. February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Denis Villeneuve Still Has a "Dream" of a 'Dune' Trilogy". Vanity Fair. August 28, 2023.

- ^ Touponce 1988, p. 4.

- ^ "Frank Herbert Is Dead at 65; Author of the 'Dune' Novels". The New York Times. Associated Press. February 13, 1986. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Herbert, Frank (1990). Dune. Turtleback. ISBN 978-0881036367. Retrieved January 21, 2018 – via Google Books.

Frank Herbert was born Franklin Patrick Herbert Jr. in Tacoma, Washington on October 8, 1920.

- ^ "Herbert, Frank Patrick (1920-1986)". historylink.org. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ O'Reilly, Timothy (1981). Frank Herbert. Frederick Ungar Publishing Company. p. 14.

- ^ a b c Herbert, Brian (2003). Dreamer of Dune: The Biography of Frank Herbert.

- ^ a b c Herbert, Brian (April 19, 2003). Dreamer of Dune: The Biography of Frank Herbert. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4299-5844-8.

- ^ "Frank Herbert, author of sci-fi best sellers, dies". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. February 13, 1986. Archived from the original on February 16, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- ^ Beck, Katherine (June 9, 2021). "Herbert, Frank Patrick (1920–1986)". HistoryLink. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021.

- ^ "Marin County: Newspaper Obituaries of AIDS Victims (1984–1994)". Marin Independent Journal. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ Cohen, Geoff (2000). "Herbert, Frank (1920-1986), science fiction writer". American National Biography. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1603065. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ Irene Slattery had been a former student of Jung's in Zurich. See Touponce 1988, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Turner, Paul (October 1973). "Vertex Magazine Interview". Vertex Magazine. Vol. 1, no. 4. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved October 21, 2012 – via "The Prelude to Dune Trilogy" at members.multimania.co.uk/Fenrir/ctdinterviews.htm.

Well, I did read some Heinlein. I shouldn't really tie it down to ten years because I had read H. G. Wells. I'd read Vance, Jack Vance, and I became acquainted with Jack Vance about that time ... I read Poul Anderson.

- ^ a b c Frank Herbert at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDB). Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gina Macdonald, "Herbert, Frank (Patrick)", in Twentieth-Century Science-Fiction Writers by Curtis C. Smith. St. James Press, 1986, ISBN 0-912289-27-9 (pp. 331–334).

- ^ Richards, Linda L. "The Sons of Dune". January Magazine. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ^ "Frank Herbert _ AcademiaLab". academia-lab.com. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ "Frank Herbert _ AcademiaLab". academia-lab.com. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ "Frank Herbert _ AcademiaLab". academia-lab.com. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ Fagan, Damian. "From the Dunes of Arrakis to the Oregon Coast". The Source Weekly - Bend. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ Augustry, The (October 16, 2021). "Frank Herbert 1969 Willis E. McNelly DUNE Tape Interview - Transcript". The Augustry. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ Stamets, Paul (2011). Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World. Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale. ISBN 978-1-60774-124-4.

- ^ "SciFi Dune: Dune Genesis by Frank Herbert". courses.oermn.org. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ a b "BBC – h2g2". Edited guide entry, Frank Patrick Herbert, Jr. – Author. British Broadcasting Corporation. October 28, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ "Sandworms of Dune Blog". Frankherbert.org. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ a b Liukkonen, Petri. "Frank Herbert". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014.

- ^ "Herbert, Frank" Archived October 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. The Locus Index to SF Awards: Index of Literary Nominees. Locus Publications. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ Islam Sumatera Utara, Institutional Repository Universitas (October 18, 2024). "Chapter I,II.pdf" (PDF). Institutional Repository Universitas Islam Sumatera Utara.

- ^ "Frank Herbert | Biography, Books, Dune, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. October 4, 2024. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ Herbert, Brian. Dreamer of Dune: The Biography of Frank Herbert. New York: Tor Books, 2003, pp. 257–258, ISBN 0-765-30646-8 "[Frank Herbert completed] a half-hour documentary film based upon fieldwork he had done with Roy Prosterman in Pakistan [and] Vietnam ... Entitled The Tillers, it was written, filmed and directed by Frank Herbert. ... it appeared on King Television in Seattle and on the Public Broadcasting System."

- ^ Herbert quoted in Murray, Donald Morison (Editor) Shoptalk: learning to write with writers (1990) Cook Publishers, 1990.

- ^ a b Touponce 1988.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (September 24, 2006). "Across the Universe: 'Dune' Babies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ Shawn Speakman, Website History, Terrybrooks.net, archived from the original on September 14, 2012, retrieved June 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Herbert, Frank P. (1987). Chapterhouse: Dune. New York City: The Berkley Publishing Group, Ace Books. pp. 59, 436. ISBN 0-441-10267-0 – via Internet Archive.

It was typical of her that she wanted me to call the radiologist whose treatment in 1974 was the proximate cause of her death and thank him...

- ^ "Octocon II". Fancyclopedia. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "Octocon". Fanllore. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Lytle, Leslie (October 7, 2021). "Dune's Creator: A Glimpse of Genius". Sewanee Mountain Messenger. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "Author of 'Dune' claimed by cancer - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Durrani, Haris A. (December 31, 2021). "Frank Herbert, the Republican Salafist". New Line Magazine.

- ^ Berry, Michael (August 13, 2015). ""Dune," climate fiction pioneer: The ecological lessons of Frank Herbert's sci-fi masterpiece were ahead of its time". Salon.

- ^ Dite, Chris (August 27, 2021). "What Draws Us to the Reactionary Darkness of Dune?". Jacobin.

- ^ Kunzru, Hari (July 3, 2015). "Dune, 50 years on: how a science fiction novel changed the world". The Guardian.

- ^ Beck, Katherine (June 9, 2021). "Herbert, Frank Patrick (1920-1986)". HistoryLink.

- ^ Herbert, Brian (2003). Dreamer of Dune: The Biography of Frank Herbert. MacMillan. p. 91. ISBN 978-0765306463. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "This was Frank Herbert, speaking from his own heart... It was a philosophy of non-violence that would ultimately lead to his involvement in the movement to stop the war in Vietnam." Herbert, Brian. (2003). Dreamer of Dune: The Biography of Frank Herbert. MacMillan. Retrieved February 13, 2015 (p. 157).

- ^ Herbert, Brian (2003). Dreamer of Dune: The Biography of Frank Herbert. MacMillan. ISBN 978-1429958448. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "Dune Genesis by Frank Herbert" (PDF). Vasil.ludost.net. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ^ Stone, Pat (May 1, 1981). "Frank Herbert: Science Fiction Author". MotherEarthNews.

- ^ Frank Herbert speaking at UCLA 4/17/1985. Retrieved April 24, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "With its blend (or sometimes clash) of complex intellectual discourse and Byzantine intrigue, Dune provided a template for FH's more significant later works. Sequels soon began to appear which carried on the arguments of the original in testingly various manners and with an intensity of discourse seldom encountered in the sf field. Dune Messiah (1969) elaborates the intrigue at the cost of other elements, but Children of Dune (1976) recaptures much of the strength of the original work and addresses another recurrent theme in FH's work – the evolution of Man, in this case into SUPERMAN;..." "Frank Herbert", The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

- ^ Herbert, Frank (July 1980). "Dune Genesis". Omni. FrankHerbert.org. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ McNeilly, Willis E. "Herbert, Frank (Patrick)" in Gunn, James. The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. London, Viking, 1988. (pp. 222–24) ISBN 0-670-81041-X . "Herbert felt strongly about many causes, particularly ecology ..."

- ^ "When I was quite young ... I began to suspect there must be flaws in my sense of reality ... But I had been produced to focus on objects (things) and not on systems (processes)." Frank Herbert, "Doll Factory, Gun Factory", (1973 Essay), reprinted in The Maker of Dune: Thoughts of a Science Fiction Master edited by Tim O'Reilly. Berkley Books, 1987, ISBN 0425097854.

- ^ "Frank Herbert's true stroke of genius consisted ... in inviting a way of thinking about humanity, history, religion, and politics as complex and interdependent as ecosystems themselves". Jeffery Nicholas, Dune and Philosophy: Weirding Way of Mentat. Open Court Publishing, 2011, ISBN 0812697154, (p. 149).

- ^ "Dune, 50 years on: how a science fiction novel changed the world". The Guardian. July 3, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ O'Reilly, Tim. Frank Herbert. New York, NY: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., Inc. ,1981. (pp.59–60) ISBN 0-8044-2666-X . "Much of the Bene Gesserit technology of consciousness is based on the insights of general semantics, a philosophy and training method developed in the 1930s by Alfred Korzybski. Herbert had studied general semantics in San Francisco at about the time he was writing Dune. (At one point, he worked as a ghostwriter for a nationally syndicated column by S. I. Hayakawa, one of the foremost proponents of general semantics.)"

- ^ Budrys, Algis (April 1966). "Galaxy Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 67–75.

- ^ Touponce 1988, p. 2"His dominant intellectual impulse was not to mystify or set himself up as a prophet, but the opposite – to turn what powers of analysis he had (and they were considerable) over to his audience. And this impulse is as manifest in Dune, which many people consider the all-time best science fiction novel, as it is in his computer book, Without Me You're Nothing."

- ^ "Bibliography: Dune". ISFDB. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ Building Sci-fi Moviescapes: The Science Behind the Fiction by Matt Hanson.

- ^ "Frank Herbert Biography Author Page". bestsciencefictionbooks.com.

- ^ Herbert, Frank (January 1977). Dune (Berkley Medallion ed.). US: Berkley Publishing Corp. p. Back Cover. ISBN 0425-04376-2.

- ^ a b Speaking at the 2006 induction of Herbert in the Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Kevin J. Anderson stated that Children of Dune (1976) "was the first SF novel ever to hit the New York Times bestseller list." Dune 7 Blog: Wednesday, June 21, 2006: The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Archived July 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. By KJA. Dune: The Official Website. Retrieved July 17, 2011. KJA spoke and presented the award to son Brian Herbert.

- ^ Malcolm Edwards, "Herbert, Frank" in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, edited by John Clute and Peter Nicholls. London, Orbit, 1994. ISBN 1-85723-124-4 (p. 558–560).

- ^ "Presenting the 2006 Hall of Fame Inductees". Archived from the original on April 26, 2006. Retrieved August 19, 2016.. Press release March 15, 2006. Science Fiction Museum (sfhomeworld.org). Archived April 26, 2006. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ "Science Fiction Hall of Fame". The Cohenside. May 15, 2006. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ "Remembering Science Fiction Author Frank Herbert: Highlighting His Archives In the Pollak Library". California State University, Fullerton. February 27, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Krell, Alexis (July 6, 2019). "The Dune Peninsula and Frank Herbert Trail — 'Tacoma's newest treasure' — are open". The Tacoma News-Tribune. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ Anderson, Kevin J. (March 16, 2012). "New, never-published Frank Herbert novel now available: HIGH-OPP". KJAblog.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Anderson, Kevin J. (May 22, 2013). "New, Previously Unpublished Frank Herbert Novel, ANGELS' FALL". KJAblog.com. Archived from the original on September 16, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Anderson, Kevin J. (July 9, 2013). "A GAME OF AUTHORS – another lost Frank Herbert novel". KJAblog.com. Archived from the original on September 16, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Anderson, Kevin J. (November 22, 2014). "Off the Radar". KJAblog.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ Liptak, Andrew (September 13, 2016). "The authors of Navigators of Dune on building an epic, lasting world". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

Quinn, Judy (November 17, 1997). "Bantam Pays $3M for Dune Prequels by Herbert's Son". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

The new prequels ... will be based on notes and outlines Frank Herbert left at his death in 1986.

Anderson, Kevin J. (December 16, 2005). "Dune 7 blog: Conspiracy Theories". Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2008 – via DuneNovels.com.

Frank Herbert wrote a detailed outline for Dune 7 and he left extensive Dune 7 notes, as well as stored boxes of his descriptions, epigraphs, chapters, character backgrounds, historical notes—over a thousand pages worth.

- ^ Neuman, Clayton (August 17, 2009). "Winds of Dune Author Brian Herbert on Flipping the Myth of Jihad". AMC. Archived from the original on September 21, 2009. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

I got a call from an estate attorney who asked me what I wanted to do with two safety deposit boxes of my dad's ... in them were the notes to Dune 7—it was a 30-page outline. So I went up in my attic and found another 1,000 pages of working notes.

"Before Dune, After Frank Herbert". Amazon.com. 2004. Archived from the original on April 9, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

Brian was cleaning out his garage to make an office space and he found all these boxes that had 'Dune Notes' on the side. And we used a lot of them for our House books.

"Interview with Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson". Arrakis.ru. 2004. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

We had already started work on House Atreides ... After we already had our general outline written and the proposal sent to publishers, then we found the outlines and notes. (This necessitated some changes, of course.)

- ^ Ascher, Ian (2004). "Kevin J. Anderson Interview". DigitalWebbing.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved July 3, 2007.

... we are ready to tackle the next major challenge—writing the grand climax of the saga that Frank Herbert left in his original notes sealed in a safe deposit box ... after we'd already decided what we wanted to write ... They opened up the safe deposit box and found inside the full and complete outline for Dune 7 ... Later, when Brian was cleaning out his garage, in the back he found ... over three thousand pages of Frank Herbert's other notes, background material, and character sketches.

Adams, John Joseph (August 9, 2006). "New Dune Books Resume Story". SciFi.com. Archived from the original on December 19, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

Anderson said that Frank Herbert's notes included a description of the story and a great deal of character background information. 'But having a roadmap of the U.S. and actually driving across the country are two different things,' he said. 'Brian and I had a lot to work with and a lot to expand...'

Snider, John C. (August 2007). "Audiobook Review: Hunters of Dune by Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson". SciFiDimensions.com. Archived from the original on March 24, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

the co-authors have expanded on Herbert's brief outline

Sources

edit- Touponce, William F. (1988). Frank Herbert. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-7514-5. OCLC 16717899.

Further reading

edit- Allen, L. David. Cliffs Notes on Herbert's Dune & Other Works. Lincoln, NE: Cliffs Notes, 1975. ISBN 0-8220-1231-6

- Clarke, Jason. SparkNotes: Dune, Frank Herbert. New York: Spark Publishing, 2002. ISBN 1-58663-510-7

- Grazier, Kevin R., ed. (2008). The Science of Dune: An Unauthorized Exploration into the Real Science Behind Frank Herbert's Fictional Universe. Psychology of Popular Culture. Dallas, TX: BenBella Books. ISBN 978-1-933771-28-1.

- Herbert, Brian. Dreamer of Dune : The Biography of Frank Herbert. New York: Tor Books, 2003. ISBN 0-765-30646-8

- Levack, Daniel JH; Willard, Mark. Dune Master: A Frank Herbert Bibliography. Westport, CT: Meckler, 1988. ISBN 0-88736-099-8

- McNelly, Dr. Willis E. (ed.) The Dune Encyclopedia. New York: Berkeley Publishing Group, 1984. ISBN 0-425-06813-7

- Miller, David M. Starmont Reader's Guide 5: Frank Herbert. Mercer Island, WA: Starmont, 1980. ISBN 0-916732-16-9

- O'Reilly, Timothy. Frank Herbert. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1980.

- O'Reilly, Timothy (ed.) The Maker of Dune. New York: Berkeley Publishing Group, 1987.

External links

edit- Official website for Brian Herbert and Kevin Anderson

- Frank Herbert SF Hall of Fame induction (Kevin Anderson report with his speech)

- "Frank Herbert biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

- Paul Turner (October 1973). "Vertex Interviews Frank Herbert". Volume 1, Issue 4. Archived from the original on May 19, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2005.

- 1984 interview with L. A. Reader: part 1, 2, 3

- Frank Herbert on the Literature Map

Biography and criticism

edit- Frank Herbert biography at the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

- Arabic and Islamic themes in Frank Herbert's Dune novels

- Study by Tim O'Reilly of Frank Herbert's work up to the Jesus Incident; one of the more in-depth studies of Frank Herbert's thoughts and ideas

- Article on the inspirations for Dune

- "Frank Herbert, the Dune Man" – (Frederik Pohl)

Bibliography and works

edit- Works by Frank Herbert at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Frank Herbert at the Internet Archive

- Works by Frank Herbert at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Frank Herbert at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Frank Herbert at the Internet Book List

- Frank Herbert at the Internet Book Database of Fiction

- Works by Frank Herbert at Open Library