The conservation and restoration of human remains involves the long-term preservation and care of human remains in various forms which exist within museum collections. This category can include bones and soft tissues as well as ashes, hair, and teeth.[1] Given the organic nature of the human body, special steps must be taken to halt the deterioration process and maintain the integrity of the remains in their existing state.[2] These types of museum artifacts have great merit as tools for education and scientific research, yet also have unique challenges from a cultural and ethical standpoint. Conservation of human remains within museum collections is most often undertaken by a conservator-restorer[3] or archaeologist.[4] Other specialists related to this area of conservation include osteologists and taxidermists.

Types of human remains in museums

editMuseum collections contain human remains in diverse forms, including entire preserved bodies, discrete parts of the anatomy, and even art and artifacts created out of human body parts.

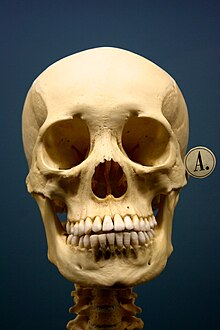

Osteological specimens

editMuseum collections, especially those of natural history, may contain human osteological specimens such as individual bones, bone fragments, entire skeletons, and teeth from both ancient and contemporary sources. Reconstruction of bone fragments should be conducted with great care and consideration. Due to the porous nature of bones, few adhering substances can be used on bone with an adequate level of reversibility, which is a key factor of conservation treatments.[5]

Mummies, preserved bodies, other human remains

editThere are innumerable types of artifacts present in museum collections that include or are composed of human remains, some with great scientific or medical merit and others with great cultural importance. Not only do the body parts vary greatly, but so do their methods of preservation.

Mummies

editMummies, though typically thought of as an Egyptian phenomenon, exist in many cultures and have been found on nearly every continent.

The word mummy can refer to both intentionally and naturally preserved bodies and is not limited to one geographic area or culture.[6] Damage of mummified remains can be caused by several factors, including poor environmental conditions, physical damage, and improper methods of preservation.[6]

Controlling environmental conditions is highly important in preserving the integrity of mummies. Fungi, pests, and microorganisms that cause decay are some of the possible results of inadequate storage and environmental factors. There are a number of ways to mitigate the effects of improper conditions, however. Methods of stabilizing mummies and halting deterioration include inert gas control, where the mummy is placed in a chamber or bag into which fumigants are introduced; wet sterilization, where solutions are applied to the mummy to repel insects and the growth of fungi; controlled drying, which reduces the relative humidity in order to stop growth of microorganisms; and ultraviolet irradiation, which kills microorganisms.[7]

Some previous treatments which were thought to help preserve mummified remains but ultimately led to further damage include curing remains by smoking them and applying solutions of copper salts to exposed skin.[6]

The Artefact Lab at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum) provides examples and images of mummy preservation.[8] The lab's collection offers insight into ongoing conservation projects on mummies and related artifacts in their collection.

Bog bodies

editBog bodies are human remains which have been discovered in peat bogs around the world. They have been preserved naturally to varying degrees due to the specific conditions of peat bogs. Despite their natural preservation, these remains are sensitive to deterioration after being removed from their original locations. Freeze-drying is an accepted method of preserving bog bodies in museum collections.[9] Some bog body discoveries include the Tollund Man of Denmark, the Elling Woman of Denmark, the Cashel Man of Ireland, the Huldremose Woman of Denmark, the Girl of the Uchter Moor of Germany, the Lindow Man of England, and the Yde Girl of the Netherlands. For a more comprehensive list of examples, see List of bog bodies.

A record of the preservation of the Tollund Man's head, which took place in 1951 and involved replacing the bog water in the cells with liquid paraffin wax, can be read on the Tollund Man's website hosted by the Silkeborg Public Library, Silkeborg Museum, and Amtscentret for Undervisning.

Soft tissues

editSoft tissues are usually in some sort of state of preservation prior to entering a museum collection, but still require periodic care.

- Plastination: One method of preserving tissues is plastination, invented by Gunther von Hagens and made famous by the exhibition Body Worlds. The process of plastination involves replacing the water and fat of a specimen with a curable polymer.[10] This form of preservation requires little upkeep in terms of conservation, other than periodic surface cleaning.

- Wet specimens: A more classic form of soft tissue preservation is in a solution of formaldehyde, creating what is known as a wet specimen. The Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, PA has an extensive collection of wet specimens of human body parts, including both normal specimens and medical abnormalities. Care and hazards of wet specimens can be found on the website of the American Museum of Natural History.[11]

Skin

editSections of human skin can be found in the collections of some museums. Some examples of this include books bound with human skin (anthropodermic bibliopegy) and preserved tattoos. The largest collection of the latter can be found in the Wellcome Collection at the Science Museum, London.

American artist Andrew Krasnow has caused controversy in recent decades by creating pieces of contemporary art made of human skin. His works, which often make political statements, are composed of pieces of flesh from individuals who have donated their bodies to science. The skin itself has been preserved by tanning.[12]

Hair

editHair is considered human remains by some definitions. It is not uncommon within museum collections due to the trend of creating "hairwork", popular during the Victorian era.[13] Locks of hair, hair wreaths, and jewelry made of hair are some of the most commonly found forms.

Caring for human remains

editThough there is great variety in human remains within museum collections as well as the ways in which they can be preserved, there are a number of best practices to be observed in the preventive care of these types of artifacts. Preventive conservation is the best method of preserving human remains in the long term, as active conservation work should be limited both by conservators' policy to interfere as little as possible and the beliefs of many indigenous tribes and groups who disapprove of altering human remains.[14]

Storage

editOne of the greatest threats to the long-term well being of human remains in museum collections is improper storage and packing.[15] Proper storage of human remains is not only necessary for their physical preservation, but it also demonstrates the respect that sensitive materials such as these should be accorded.[16] The ideal storage location for sacred artifacts and human remains is a designated space away from the rest of the collection; however, there are often many constraints which prevent this from being possible.[17] At the minimum, ethical guidelines suggest that remains from different individuals should be stored in separate boxes or compartments from each other.[18] Generally speaking, human remains are best preserved in cool, dark, dry conditions while wrapped in acid-free (non-buffered) tissue and packing materials.[19] Corporeal materials should not be stored in or near any wood or in any containers which previously housed wood due to potentially increased lignin levels, which produce an acid that can lead to the deterioration of DNA and proteins in the remains.[18] Excessive exposure to light should be avoided in order to prevent bleaching of materials, especially bone.[2]

Temperature and relative humidity

editOrganic materials are porous by nature, which means that they are greatly affected by changes in the moisture levels of their surroundings.[2] Overly moist conditions can lead to growth of fungi on protein materials like human remains, which is one of the most common risks they face.[19][20] Alternately, low-humidity conditions can potentially cause protein materials to crack, split, and shrink.[19] Ideal storage conditions for bones is 35% to 55% relative humidity with minimal fluctuations,[2] while ideal conditions for the preservation of mummies are 50 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit (10 to 15 degrees Celsius) with a relative humidity of 40% to 55%.[6]

Handling

editEmbrittlement is a risk for many human remains, and as a result handling should be limited. When possible, artifacts should be lifted by their storage container or tray. To avoid transfer of oils to the remains, nitrile or latex gloves should be worn during their handling. If a body is to be lifted, it must be supported under all of its appendages.[21]

Cleaning

editCleaning of human remains varies by type. If necessary, surface cleaning of bone can be done with a very mild detergent and water solution, but bones should never be soaked in order to prevent dirt from becoming embedded in pores.[2] The possibility of cleaning human remains is highly dependent on the fragility of the specimen.

Cultural and ethical considerations

editThere are many challenges surrounding human remains accessioned by museums, including legal complications involved in dealing with human remains, involvement of living relatives or tribes, and potential repatriation and issues such as the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA).[1] NAGPRA requires any federal or federally-funded institution, with the exception of the Smithsonian Institution, to submit full inventories of their Native American funerary and sacred objects and human remains and to repatriate these objects to their tribe of origin should a request be made to do so.[1] Should a museum possess human remains which have a direct living relative or group (Native American or otherwise), it is their ethical obligation to involve these individuals in the care and treatment of the remains.[22]

Acquisition of human remains by museums can happen in a number of ways, some of which are considered to be unethical today. Many museums have human remains in their collections which have been there for over a hundred years, in which case they may likely have been acquired in ethically or morally unsound ways.[23][24] This has led to growing concerns that the display of human remains has become depersonalised, by continuing to keep them in collections.[25] Most institutions and museum associations have their own policies on the acquisition of human remains. Some guidelines for the care of human remains including acceptable means of acquisition can be found below.

Scientific analyses

editCultural considerations can sometimes interfere with the conservation of human remains, particularly when it comes to physical and chemical analyses, which play an important role in their care.[26] Testing conducted on human remains, especially ancient ones, can include DNA testing, isotope analyses, and carbon-14 dating.[26] The benefits of such testing is sometimes outweighed by the cultural or sacred importance of the remains as well as the risk of damaging them too greatly.[26] According to the Deutscher Museumsbund, there are only three circumstances in which scientific research should be conducted on human remains:

- there is a great deal of scientific interest

- the human remains have a known provenance, and

- the method of acquisition of the human remains is no source for concern.[27]

Case study

editThe Kennewick Man is a notable example of human remains caught in a struggle between scientific merit and cultural traditions. Since his discovery in 1996, his fate has been the topic of great controversy. As one of the oldest well-preserved ancient skeletons found in America, scientists are eager to conduct various testing on the remains. Native American groups, however, have been adamantly calling for his repatriation and reburial, as per their traditions.[28]

References

edit- ^ a b c McKeown, C. Timothy; Murphy, Amanda; Schansberg, Jennifer (2010). "Complying with NAGPRA". In Buck, Rebecca; Gilmore, Jean Allman (eds.). Museum Registration Methods 5th Edition. Washington, D.C.: The AAM Press. pp. 449–457.

- ^ a b c d e Pouliot, Bruno P. (2000). "Organic Materials". The Winterthur Guide to Caring for Your Collection. Hanover: University Press of New England. pp. 45–56.

- ^ Wesche, Anne, ed. (2013). Recommendations for the Care of Human Remains in Museums and Collections (PDF). Germany: Deutscher Museumsbund e.V. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Berger, Stephanie (2013). "Treating Bones: The Intersection of Archaeology And Conservation" (PDF). University of Michigan. p. 10.

- ^ LaRoche, Cheryl J.; McGowan, Gary S. (1996). "The Ethical Dilemma Facing Conservation: Care and Treatment of Human Skeletal Remains and Mortuary Objects" (PDF). Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. Vol. 35, no. 2. pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b c d David, A. Rosalie (2001). "Benefits and Disadvantages of Some Conservation Treatments for Egyptian Mummies". Chungara: Revista de Antropología Chilena. Universidad de Tarapaca. p. 113. JSTOR 27802173.

- ^ David, A. Rosalie (2001). "Benefits and Disadvantages of Some Conservation Treatments for Egyptian Mummies". Chungara: Revista de Antropología Chilena. Universidad de Tarapaca. p. 114. JSTOR 27802173.

- ^ University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. "In the Artifact Lab". www.penn.museum.

- ^ Omar, S.; McCord, M.; Daniels, V. (1989). "The Conservation of Bog Bodies by Freeze-Drying". Studies in Conservation. Vol. 34, no. 3. Maney Publishing. pp. 101–109. JSTOR 1506225.

- ^ von Hagens, Gunther; Tiedemann, Klaus; Kriz, Wilhelm (1987). "The current potential of plastination". Anatomy and Embryology. Vol. 4, no. 175. pp. 411–421.

- ^ "Fluid Preserved Specimens". American Museum of Natural History.

- ^ Johnson, Andrew (23 October 2011). "Body art. Literally". Independent.

- ^ "History of Hair Art". Leila's Hair Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-12-26. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ Berger, Stephanie (2013). "Treating Bones: The Intersection of Archaeology And Conservation" (PDF). University of Michigan. p. 29.

- ^ Berger, Stephanie (2013). "Treating Bones: The Intersection of Archaeology And Conservation" (PDF). University of Michigan. p. 34.

- ^ LaRoche, Cheryl J.; McGowan, Gary S. (1996). "The Ethical Dilemma Facing Conservation: Care and Treatment of Human Skeletal Remains and Mortuary Objects" (PDF). Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. Vol. 35, no. 2. p. 116.

- ^ Deutscher Museums Bund (April 2013). "Recommendations for the Care of Human Remains in Museums and Collections" (PDF). p. 53. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ a b Deutscher Museums Bund (April 2013). "Recommendations for the Care of Human Remains in Museums and Collections" (PDF). p. 52. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ a b c Rose, Carolyn L. (1992). "Preserving Ethnographic Objects". Conservation Concerns: A Guide for Collectors and Curators. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books. pp. 117–118.

- ^ Berger, Stephanie (2013). "Treating Bones: The Intersection of Archaeology And Conservation" (PDF). University of Michigan.

- ^ Neilson, Dixie (2010). "Object Handling". In Buck, Rebecca; Gilmore, Jean Allman (eds.). Museum Registration Methods 5th Edition. Washington, D.C.: The AAM Press. pp. 209–218.

- ^ Deutscher Museums Bund (April 2013). "Recommendations for the Care of Human Remains in Museums and Collections" (PDF). pp. 54–55. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ Edwards, Alison (2010). "Care of Sacred and Culturally Sensitive Objects". In Buck, Rebecca; Gilmore, Jean Allman (eds.). Museum Registration Methods 5th Edition. Washington, D.C.: The AAM Press. p. 408.

- ^ Huffer Damien, Graham Shawn (2017). "The Insta-Dead: The rhetoric of the human remains trade on Instagram". Internet Archaeology (45). doi:10.11141/ia.45.5.

- ^ Shelbourn, Carolyn (2006). "Bringing the Skeletons out of the Closet: The Law and Human Remains in Art, Archaeology and Museum Collections". Art Antiquity and Law. 11 (2): 179–198, 181.

- ^ a b c LaRoche, Cheryl J.; McGowan, Gary S. (1996). "The Ethical Dilemma Facing Conservation: Care and Treatment of Human Skeletal Remains and Mortuary Objects" (PDF). Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. Vol. 35, no. 2. p. 109.

- ^ Deutscher Museums Bund (April 2013). "Recommendations for the Care of Human Remains in Museums and Collections" (PDF). p. 55. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ Preston, Douglas (September 2014). "The Kennewick Man Finally Freed to Share His Secrets". Smithsonian Magazine.

Further reading

edit- Jenkins, Tiffany (2011). Contesting Human Remains in Museum Collections: the crisis of cultural authority. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415879606.

- Lohman, Jack; Goodnow, Katherine, eds. (2006). Human Remains & Museum Practice. Paris/London: UNESCO Publishing/Museum of London. ISBN 9789231040214.

- Graham, Shawn; Huffer, Damian (2020). "Reproducibility, Replicability, and Revisiting the Insta-Dead and the Human Remains Trade". Internet Archaeology (55). doi:10.11141/ia.55.11.

- The Bonetrade: Studying the online trade in human remains with machine learning and neural networks

External links

edit- Guidance for the Care of Human Remains in Museums, published by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (England, Wales, and Northern Ireland)

- Introduction to human remains in museums, published by Museum Galleries Scotland

- Recommendations for the Care of Human Remains in Museums and Collections, published by Deutscher Museumsbund (German Museums Association)

- Full Wellcome Trust policy on the care of human remains in museums and galleries