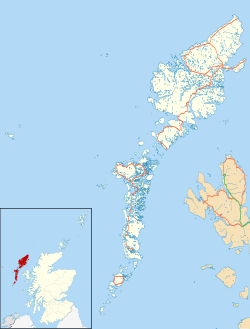

Cladh Hallan (Scottish Gaelic: Cladh Hàlainn, Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [kʰl̪ˠɤɣ ˈhaːl̪ˠɪɲ]) is an archaeological site on the island of South Uist[1][2] in the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. It is significant as the only place in Great Britain where prehistoric mummies have been found.[3][4] Excavations were carried out there between 1988 and 2002, which indicate the site was occupied from 2000 BC.[5][6]

Remains of roundhouses at Cladh Hallan | |

| Location | South Uist |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 57°10′16″N 7°24′27″W / 57.17116°N 7.40759°W |

| History | |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

| Site notes | |

| Public access | Yes |

blue: male c. 1600 BC

yellow: male c. 1500-1400 BC

red: male c. 1440-1360 BC

In 2001, a team of archaeologists found four skeletons at the site, one of them a male who had died c. 1600 BC, and another a female who had died c. 1300 BC. At first, the researchers did not realise they were dealing with mummies, since the soft tissue had decomposed and the skeletons had been buried.[7] But tests revealed that the two bodies had not been buried until about 1120 BC[8] and that the bodies had been preserved shortly after death in a peat bog for 6 to 18 months. The preserved bodies were then apparently retrieved from the bog and set up inside a dwelling, presumably having religious significance. Archaeologists do not know why the bodies were buried centuries later. The Cladh Hallan skeletons differ from most bog bodies in two respects: unlike most bog bodies, they appear to have been put in the bog for the express purpose of preservation (whereas most bog bodies were simply interred in the bog), and unlike most bog bodies, their soft tissue was no longer preserved at the time of discovery.

The high level of the calcareous sand in Cladh Hallan and the Scottish Highlands had been attributed in part to the preservation of the mummies over thousands of years.[9]

Analysis

editThis section needs to be updated. (January 2017) |

The skeletons and other finds are being analysed in laboratories in Scotland, England and Wales. Following the provisions of the Treasure Trove Act, all the finds from Cladh Hallan, including the skeletons, will be allocated to a Scottish museum after the lengthy process of analysis and reporting is completed. According to recent anthropological and DNA-analysis, the skeletons of a female and a male were compiled from body parts of at least 6 different human individuals.[8][10]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Pearson, Mike Parker; Chamberlain, Andrew; Craig, Oliver; Marshall, Peter; Mulville, Jacqui; Smith, Helen; Chenery, Carolyn; Collins, Matthew; Cook, Gordon; Craig, Geoffrey; Evans, Jane; Hiller, Jen; Montgomery, Janet; Schwenninger, Jean-Luc; Taylor, Gillian (September 2005). "Evidence for mummification in Bronze Age Britain". Antiquity. 79 (305): 529–546. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00114486. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 53392023.

- ^ Pearson, Michael Parker (2012). From Machair to Mountains: Archaeological Survey And Excavation in South Uist. Oxbow Books. hdl:20.500.12657/53457. ISBN 978-1-78925-887-5.

- ^ Booth, Thomas J.; Chamberlain, Andrew T.; Pearson, Mike Parker (2015). "Mummification in Bronze Age Britain". Antiquity. 89 (347): 1155–1173. doi:10.15184/aqy.2015.111. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 161304254.

- ^ "Mummification in Bronze Age Britain" BBC History. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "The Prehistoric Village at Cladh Hallan". University of Sheffield. Retrieved 21 Feb 2008.

- ^ Pearson, Mike Parker; Mulville, Jacqui; Smith, Helen; Marshall, Peter (31 October 2021). Cladh Hallan - Roundhouses and the dead in the Hebridean Bronze Age and Iron Age: Part I: Stratigraphy, Spatial Organisation and Chronology. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78925-696-3.

- ^ Pearson, Mike Parker; Chamberlain, Andrew; Craig, Oliver; Marshall, Peter; Mulville, Jacqui; Smith, Helen; Chenery, Carolyn; Collins, Matthew; Cook, Gordon; Craig, Geoffrey; Evans, Jane; Hiller, Jen; Montgomery, Janet; Schwenninger, Jean-Luc; Taylor, Gillian (2005). "Evidence for mummification in Bronze Age Britain". Antiquity. 79 (305): 529–546. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00114486. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 53392023.

- ^ a b Hanna, Jayd; Bouwman, Abigail S.; Brown, Keri A.; Parker Pearson, Mike; Brown, Terence A. (1 August 2012). "Ancient DNA typing shows that a Bronze Age mummy is a composite of different skeletons". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (8): 2774–2779. Bibcode:2012JArSc..39.2774H. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.04.030. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ Parker Pearson, Mike; Mulville, Jacqui; Smith, Helen; Marshall, Peter; Booth, Tom; Brennand, Mark; Chamberlain, Andrew; Cook, Gordon; Craig, Oliver; de Luis, Irene; Evans, Jane; French, Charles; Hale, Alexandra; Hamlet, Laura; Hiller Bardsley, Jen; Manley, Harry; Montgomery, Janet; Moth, Edwin; Parsons, Vicky; Peto, Jessica; Rhodes, Shaun; Schwenninger, Jean-Luc; Simpson, Ian; Willis, Christie (2021). Cladh Hallan: roundhouses and the dead in the hebridean bronze age and iron age (Hardback ed.). Philadelphia: Oxbow Books. pp. 1–25. doi:10.2307/j.ctv24q4zc4.7. ISBN 978-1789256932. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ Kaufman, Rachel (6 July 2012). ""Frankenstein" Bog Mummies Discovered in Scotland; Two ancient bodies made from six people, new study reveals". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

Further reading

edit- Parker Pearson, Michael; et al. (2004). South Uist: Archaeology and History of a Hebridean Island. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2905-1.

External links

edit- grid reference NF7308121962

- South Uist, Cladh Hallan Roundhouses Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland