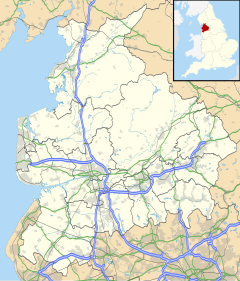

Blackpool is a seaside town in Lancashire, England. It is located on the Irish Sea coast of the Fylde peninsula, approximately 27 miles (43 km) north of Liverpool and 14 miles (23 km) west of Preston. It is the main settlement in the borough of the same name. The population of Blackpool at the 2021 census was 141,000, a decrease of 1,100 in ten years.[1]

| Blackpool | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

| Area | 34.47 km2 (13.31 sq mi) |

| Population | 141,000 (2021 census) |

| • Density | 4,091/km2 (10,600/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Blackpudlian |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BLACKPOOL |

| Postcode district | FY1-FY5 |

| Dialling code | 01253 |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | blackpool |

Blackpool was originally a small hamlet; it began to grow in the mid-eighteenth century, when sea bathing for health purposes became fashionable. Blackpool's beach was suitable for this activity, and by 1781 several hotels had been built. The opening of a railway station in 1846 allowed more visitors to reach the resort, which continued to grow for the remainder of the nineteenth century. In 1876, the town became a borough, and by 1951 its population had reached 147,000. Blackpool's development was closely tied to the Lancashire cotton-mill practice of annual factory maintenance shutdowns, known as wakes weeks, when many workers chose to visit the seaside. The local climate is mild and rainy also in summer.

In the late 20th century, changing holiday preferences and increased overseas travel impacted Blackpool's standing as a leading resort. Despite economic challenges, the town's urban fabric and economy remain centred around tourism. Today, Blackpool's seafront, featuring landmarks such as Blackpool Tower, Illuminations, Pleasure Beach, and the Winter Gardens, continue to draw millions of visitors annually.[2] The town is home to football club Blackpool F.C. The team has one major trophy, winning the 1953 FA Cup.

History

editEarly history

editIn 1970, a 13,500-year-old elk skeleton was found with man-made barbed bone points. Now displayed in the Harris Museum this provided the first evidence of humans living on the Fylde.[3] The Fylde was also home to a British tribe, the Setantii (the "dwellers in the water") a sub-tribe of the Brigantes. Some of the earliest villages on the Fylde, which were later to become part of Blackpool town, were named in the Domesday Book in 1086.[citation needed]

In medieval times Blackpool emerged as a few farmsteads on the coast within Layton-with-Warbreck, the name coming from "le pull", a stream that drained Marton Mere and Marton Moss into the sea. The stream ran through peatlands that discoloured the water, so the name for the area became "Black Poole". In the 15th century the area was just called Pul, and a 1532 map calls the area "the pole howsys alias the north howsys".[citation needed]

In 1602, entries in Bispham Parish Church baptismal register include both Poole and for the first time blackpoole. The first house of any substance, Foxhall, was built by the Tyldesley family of Myerscough Lodge and existed in the latter part of the 17th century. By the end of that century it was occupied by squire and diarist Thomas Tyldesley, grandson of the Royalist Sir Thomas Tyldesley. An Act of Parliament in 1767 enclosed a common, mostly sand hills on the coast, that stretched from Spen Dyke southwards (see Main Dyke).[citation needed]

Sea bathing and the growth of seaside resorts

editIn the 18th century, sea bathing gained popularity for health benefits, drawing visitors to Blackpool. In 1781, The town's amenities, including hotels, archery stall, and bowling greens, slowly expanded. By 1801, the population reached 473. Henry Banks, instrumental in Blackpool's growth, purchased Lane Ends estate in 1819, building the first holiday cottages in 1837.[4][5]

Arrival of the railways

editIn 1846, a pivotal event marked the early growth of the town: the completion of a railway branch line to Blackpool from Poulton. This spurred development as visitors flocked in by rail, boosting the town's economy. Blackpool prospered with the construction of accommodations and attractions, fostering rapid growth in the 1850s and 1860s. A Board of Health was established in 1851, gas lighting in 1852, and piped water in 1864. The town's population exceeded 2,500 by 1851.

Electricity

editBlackpool's growth since the 1870s was shaped by its pioneering use of electrical power. In 1879, it became the world's first municipality with electric street lighting along the promenade, setting the stage for the Blackpool Illuminations.

By the 1890s, Blackpool had a population of 35,000 and could host 250,000 holidaymakers. Notable structures, like the Grand Theatre (1894) and Blackpool Tower, emerged. The Grand Theatre was among Britain's first all-electric theatres.

In 1885, it established one of the world's earliest electric tramways, initially operated by the Blackpool Electric Tramway Company. By 1899, the tramway expanded, and the conduit system was replaced by overhead wires. The system still remains in service.

Towards the present

editThe inter-war period saw Blackpool develop and mature as a holiday destination, and by 1920 Blackpool had around eight million visitors per year, still drawn largely from the mill towns of East Lancashire and the West Riding of Yorkshire.[citation needed] Blackpool's population boom was complete by 1951, by which time some 147,000 people were living in the town – compared with 47,000 in 1901 and 14,000 in 1881.[6] The town continued to attract more visitors in the decade after the war, reaching a peak of 17 million per year.[citation needed]

By the 1960s the UK tourism industry was undergoing radical changes. The increasing popularity of package holidays took many of Blackpool's traditional visitors abroad. The construction of the M55 motorway in 1975 made Blackpool more feasible as a day trip rather than an overnight stay. The modern economy, however, remains relatively undiversified and firmly rooted in the tourism sector.[citation needed]

Geography

editPhysical

editBlackpool rests in the middle of the western edge of The Fylde, which is a coastal plain atop a peninsula. The seafront consists of a 7-mile sandy beach,[7] with a flat coastline in the south of the district, which rises once past the North Pier to become the North Cliffs, with the highest point nearby at the Bispham Rock Gardens at around 34 metres (112 ft).[8][9] The majority of the town district is built up, with very little semi-rural space such as at Marton Mere. Due to the low-lying terrain, Blackpool experiences occasional flooding,[10] with a large-scale project completed in 2017 to rebuild the seawall and promenade to mitigate this.[11]

Climate

editBlackpool has a temperate maritime climate according to the Köppen climate classification system. Typically, cool summers, frequent overcast skies and small annual temperature range fluctuations.

The minimum temperature recorded was −15.1 °C (4.8 °F),[12] recorded during December 1981, however −18.3 °C (−0.9 °F) was recorded in January 1881.[13]

The absolute maximum temperature recorded in Blackpool was 37.2 °C (99.0 °F) during a 2022 United Kingdom heat wave. During an average summer, the warmest temperature reached 28.5 °C (83.3 °F) between 1991 and 2020.[14]

Precipitation averages slightly less than 900 mm (35 in), with over 1 mm of precipitation occurring on 147 days of the year.[15]

| Climate data for Blackpool (BLK),[a] elevation: 10 m (33 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1960–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

24.4 (75.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

31.3 (88.3) |

37.2 (99.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 10.8 (51.4) |

11.1 (52.0) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.3 (79.3) |

25.2 (77.4) |

22.9 (73.2) |

18.7 (65.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

11.7 (53.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.6 (63.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.4 (50.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.6 (43.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

14.1 (57.4) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

5.2 (41.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.0 (41.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −3.8 (25.2) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

7.9 (46.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.5 (11.3) |

−13.2 (8.2) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

3.3 (37.9) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−15.1 (4.8) |

−15.1 (4.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 77.8 (3.06) |

64.0 (2.52) |

54.4 (2.14) |

48.7 (1.92) |

54.0 (2.13) |

63.1 (2.48) |

66.0 (2.60) |

79.9 (3.15) |

83.5 (3.29) |

101.4 (3.99) |

94.7 (3.73) |

99.1 (3.90) |

886.6 (34.91) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 14.4 | 11.4 | 11.2 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 10.9 | 12.2 | 11.6 | 14.4 | 15.7 | 15.6 | 147.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 55.0 | 80.4 | 119.3 | 175.5 | 217.9 | 210.1 | 201.1 | 182.6 | 141.8 | 98.0 | 60.7 | 49.3 | 1,591.7 |

| Source 1: Met Office[16] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI[17] Infoclimat[14] | |||||||||||||

- ^ Weather station is located 2.8 miles (4.5 km) from the Blackpool town centre.

Green belt

editBlackpool is within a green belt region that extends into the wider surrounding counties and is in place to reduce urban sprawl, prevent the towns in the Blackpool urban area and other nearby conurbations in Lancashire from further convergence, protect the identity of outlying communities, encourage brownfield reuse, and preserve nearby countryside. This is achieved by restricting inappropriate development within the designated areas, and imposing stricter conditions on the permitted building.[18]

As the town's urban area is highly built up, only 70 hectares (0.70 km2; 0.27 sq mi) (2017)[19] of green belt exists within the borough, covering the cemetery, its grounds and nearby academy/college playing fields by Carleton, as well as the football grounds near the airport by St Annes.[20] Further afield, portions are dispersed around the wider Blackpool urban area into the surrounding Lancashire districts of Fylde and Wyre, helping to keep the settlements of Lytham St Annes, Poulton-le-Fylde, Warton/Freckleton and Kirkham separated.[21]

Demographics

editBlackpool's population was approximately 141,000 in 2021 according to census figures – a fall of 0.7 per cent from the 2011 census.[1] It is one of five North West local authority areas to have recorded a fall in this period, during which the figure for England as a whole rose by 6.6 per cent. Blackpool is the third most densely populated local authority in the North West, with 4,046 people per square kilometre, compared with 4,773 in Manchester and 4,347 in Liverpool.[22]

In 2021, 41.0 per cent of Blackpool residents reported having 'No religion', up from 24.5 per cent in 2011. Across England the percentage increased from 24.8 per cent to 36.7 per cent. However, because the census question about religion was voluntary and has varying response rates, the ONS warns that 'caution is needed when comparing figures between different areas or between censuses'.[citation needed]

According to the 2021 census, 49.5 per cent of residents aged 16 years and over were employed (excluding full-time students, with 3.8 per cent unemployed (a drop from 5.4 per cent in 2011). The proportion of retired residents was 23.8 per cent. Just over a tenth of people aged 16 and over worked 15 hours or less a week.[citation needed]

Blackpool's population is forecast to rise slightly to 141,500 by 2044, with the 45-64-year-old group showing the greatest decrease. The number of residents over 65 years old is projected to rise to almost 36,000, making up 26 per cent of the total population.[22]

Governance and politics

editThere is just one tier of local government covering Blackpool, being the unitary authority of Blackpool Council, which is based at Blackpool Town Hall on Talbot Square.

Parts of the Blackpool Urban Area extend beyond the borough boundaries of Blackpool into the neighbouring boroughs of Wyre (which includes Fleetwood, Cleveleys, Thornton and Poulton-le-Fylde) and Fylde (which covers Lytham St Annes).

Administrative history

editBlackpool was historically part of the township of Layton with Warbreck, which was part of the ancient parish of Bispham. The township was constituted a Local Board of Health District in 1851, governed by a local board.[23][24] In 1868 the Layton with Warbreck district was renamed the Blackpool district.[25]

In 1876 the district was elevated to become a municipal borough, governed by a body formally called the "mayor, aldermen and burgesses of the borough of Blackpool", but generally known as the corporation or town council.[26] The borough was enlarged several times, notably in 1879, when it took in parts of the neighbouring parishes of Marton and Bispham with Norbreck,[27] in 1918, when it absorbed the rest of Bispham with Norbreck, and in 1934, when it absorbed the rest of Marton.[28]

In 1904 Blackpool was made a county borough, taking over county-level functions from Lancashire County Council.[29] This was reverted in 1974 when Blackpool became a lower-tier non-metropolitan district with the county council once more providing services in the town.[30] Blackpool regained its independence from the county council in 1998 when it was made a unitary authority.[31]

Blackpool remains part of the ceremonial county of Lancashire for the purposes of lieutenancy.[32]

Parliamentary constituencies

editBlackpool is covered by two Westminster constituencies:

Until 1945, the area was represented by just one constituency, named Blackpool. This was replaced by the new Blackpool North and Blackpool South constituencies. Blackpool North became Blackpool North and Cleveleys for the 2010 general election, when Conservative Paul Maynard became MP. Another Conservative, Scott Benton, won Blackpool South from longstanding Labour MP Gordon Marsden in 2019. Benton resigned on 25 March 2024, however, after the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards investigated a fake lobbying role he was offered by undercover reporters from The Times.[33]

The constituencies were reorganised for the 2024 general election, following recommendations from the Boundary Commission for England that aim to make the number of voters in the country's seats more equal.[34] Blackpool South was expanded to take in new wards near the north of the constituency. The Blackpool North and Cleveleys constituency incorporated Fleetwood and five wards from the Blackpool Council area, and was renamed Blackpool North and Fleetwood – as a similar seat was known between 1997 and 2010. In 2022 Maynard told the Blackpool Gazette: "I am sure that residents of Fleetwood will be glad to be reunited with the rest of the Fylde coast, as they are geographically."[35]

Economy

editAs a local authority area, Blackpool's gross domestic product (GDP) was approximately £3.2 billion in 2020 – 0.2 per cent of the English economy. GDP fell by 2.2 per cent between 2019 and 2020.[36]

Seventy-five per cent of people of working age in Blackpool were economically active in 2021, with 51,600 in full-time employment and 7,900 self-employed. The average for the North West is 72.9 per cent and for England is 74.8 per cent.[37]

Twenty-five per cent of jobs were in human health and social work – compared with 13.6 per cent nationally. Reflecting Blackpool's strong tourism industry, 10.9 per cent were in accommodation and food services. With aerospace company BAE situated in the wider area and the Civil Service one of its major employers, the proportion of people working in public administration, defence and compulsory social security is also higher than the national average – 12.5 per cent compared with 4.6 per cent.[38]

In a survey of the UK's 63 largest cities and towns – using primary urban areas, a measure of the built-up area rather than local authority boundaries – the think tank Centre for Cities said Blackpool's gross value added (GVA) was £5.2 billion in 2020, with GVA per hour of £32.7. That placed it at 53rd and 40th place in the survey respectively. It was also in the lower half of the rankings for business start-ups, closures and overall stock, as well as the proportion of new economy firms.[39]

Blackpool is the third lowest local authority area in the UK for gross median weekly pay. Its growth rates were forecast to be among the lowest localities in the UK Competitiveness Index 2023 - along with Blaenau Gwent (Wales), Burnley (North West), Torbay (South West), and Merthyr Tydfil (Wales).[40]

Blackpool is also the main centre of the wider Fylde Coast sub-regional economy, containing other coastal towns, including Lytham, market towns, an agricultural hinterland and some industry.[41] Polymers company Victrex, in Thornton and formerly part of ICI, is one of the major private sector companies headquartered in the area. Sports car manufacturer TVR was based in Blackpool until 2006, and national jewellery chain Beaverbrooks, founded in 1919, relocated its head office to St Annes in 1946.[citation needed]

Economic development officials highlight Blackpool's role in industry sectors including aerospace and advanced engineering, advanced materials technologies, regional energy, and food manufacturing. As well as BAE, leading aerospace companies in the area include Magellan Aerospace and Force Technology. In advanced materials, AGC and Victrex are significant companies. In energy, nuclear fuel manufacturer Westinghouse, the National Nuclear Laboratory and offshore energy companies Orsted, NVH and Helispeed all have operations in the area. Blackpool's travel to work area has 2.5 times the Great Britain-average concentration of food manufacturing workers.[42]

Conferences and exhibitions

editDuring the second half of the 20th century and up to 2007, Blackpool was one of the country's leading locations for political conferences, with the three main parties as well as bodies such as the TUC holding events at the Winter Gardens.

With the Winter Gardens in need of refurbishment and parties preferring inland city locations to coastal resorts, Blackpool held no major political conferences between 2008 and 2021. The Conservatives returned for their spring event in 2022 in the newly rebuilt Winter Gardens Conference and Exhibition Centre.[43]

Regeneration

editLike most UK coastal resorts, Blackpool declined from the 1960s onwards with the rise of overseas holidays. This coincided with a lack of investment in the town and its facilities for both residents and tourists.[44]

Fulfilment of a 1965 masterplan to remodel the town centre was "limited and piecemeal", according to Historic England.[45] Ambitious plans to redevelop the centre "stuttered to a halt in the early 1970s". Large numbers of homes were deemed unfit for human habitation and by 1993, almost 30 per cent of households did not have central heating, compared with the national average of 8.5 per cent. A new masterplan in 2003 was a response to this decline and the growing threat from coastal erosion. It was described by English Heritage as a "bold attempt to ensure the future of the town".

Blackpool had pinned its regeneration hopes on an Atlantic City– or Las Vegas–style resort casino that Leisure Parcs, then owner of Blackpool Tower and the Winter Gardens, unveiled £1 billion plans for in 2002.[46] By 2007, Blackpool and Greenwich in London were considered frontrunners among the seven bidders for Britain's first and only supercasino licence;[47] however, nearby Manchester won the bidding process. The Casino Advisory Panel ruled that the "regeneration benefits of the supercasino for Blackpool are unproven and more limited geographically than other proposals". The government later abandoned the supercasino licence altogether following a legislative defeat in the House of Lords.[48]

In response to Blackpool losing the supercasio bid and lobbying from the town's disappointed leaders, ministers increased its regeneration spending,[49] coordinated by an Urban Regeneration Company ReBlackpool, set up in 2005.[50] Before being wound up in 2010, ReBlackpool led on Central Seafront, a £73 million coastal protection scheme that brought new promenades and seawalls for the town, funded by Government, the North West Development Agency and the European Regional Development Fund.[51] ReBlackpool also prepared the Talbot Gateway scheme, appointing Muse Developments to develop 160,000 sq m of office and business space, as well as retail and hotel units, on a 10ha plot near Blackpool North Station. Blackpool Council agreed to relocate its offices to the development and there were plans for a new public transport interchange.[52]

In 2010, Blackpool Council bought landmarks Blackpool Tower, the Winter Gardens and the Golden Mile Centre from leisure entrepreneur Trevor Hemmings, aiming to refurbish them in a "last-ditch effort to arrest Blackpool's economic decline".[53] Public ownership enabled significant further investment in the facilities.[54] The restoration of the Tower's stained glass windows was carried out by local specialist Aaron Whiteside, who was given a Blackpool Council conservation award for the work.[55]

Refurbishment of the Winter Gardens conference centre was completed in time to host the Conservative Party spring conference in 2022, with further work announced in 2023.[56]

Blackpool Council was one of four local authorities in the Blackpool Fylde and Wyre Economic Development Company – the others being Lancashire County Council, Fylde Borough Council and Wyre Borough Council. It oversaw the development of the Blackpool Airport Development Zone, which came into existence in 2016.[57] It offers tax breaks and simplified planning to employers.

Blackpool Council, once again owner of the airport since it acquired it from Balfour Beatty in 2017, is seeking outline planning consent to build five new hangars and a commercial unit. The masterplan for the Blackpool Airport Enterprise Zone then envisages a new digital and technology quarter called Silicon Sands.[58][59]

In 2018, Blackpool Council announced plans for the 7-acre Blackpool Central development, on the site of Blackpool Central Station, which was closed in 1964. The council agreed to provide the land for the scheme – which had earlier been earmarked for the supercasino – but it was to be private-sector funded, led by developer Nikal.[60] It aims to provide a new public square, hotels, restaurants, a food market and car park.[61]

Talbot Gateway

editThe first phase of Talbot Gateway was completed in 2014 with the opening of the Number One Bickerstaffe Square council office, a supermarket and a refurbished multi-storey car park, and public spaces.[62]

Phase two, including a new Holiday Inn and a tram terminal for the extended tramway between North Pier and North Station, began in 2021 and was due to be completed by 2022 but has been delayed, with completion now expected in 2024.[63] But new ground floor retail units were released in July 2023.[64]

Construction started in February 2023 on new government offices as part of phase three of Talbot Gateway, and 3,000 Department for Work and Pensions staff are due to be relocated to the town after an expected completion date of March 2025.[65]

In January 2023, Blackpool and Wyre councils were awarded £40 million from the government's Levelling-Up Fund for a new education campus as part of phase four of Talbot Gateway. The campus will provide a new carbon-neutral base for Blackpool and The Fylde College.[66] This will involve "relocating" the existing Park Road campus which is considered to present challenges including dated infrastructure.[67] The future of the 1937 building on Palatine Road – designed by civic architect JC Robinson for Blackpool Technical College and School of Art – is unknown.

Blackpool Central

editPlans for Blackpool Central's multi-storey car park and Heritage Quarter were approved in October 2021, and construction of the car park began in 2022.[61] But the £300 million development was stalled because of a lack of funding to move the Magistrates and County Courts from the site. In November 2022, Levelling-Up Secretary Michael Gove said his department would award £40 million of funding to enable that relocation and "revitalise this great town by delivering much-needed homes, more jobs and new opportunities for local people".[68]

Heritage Action Zone

editThe Blackpool Heritage Action Zone (HAZ) aims to bring new uses to the town centre by restoring buildings and promoting creative activities. Blackpool is one of more than 60 locations in the UK to have Heritage Action Zones, and its initial funding of £532,575 was secured in 2020.[69]

Restoration of buildings is taking place on Topping Street, Edward Street and Deansgate, while the largest part of the scheme is the Church Street frontage of the Winter Gardens. The Art Deco building of 28 Topping Street has become a community creative hub run by Aunty Social, a voluntary arts organisation focussing on socially engaged work in gentle spaces and directed by Catherine Mugonyi[70] and a building on Edward Street is to be converted into live/work for local artists and creatives.[71]

Abingdon Street Market was partially reopened to the public in May 2023 after a three-year closure due to urgent maintenance works.[72] The Edward Street side of the market was redesigned as a food hall and space for live entertainment and community events. The retail side of the market – located via the Abingdon Street entrance – is due to open in Winter 2023. The market was purchased by the council with £3.6 million of government funding through the Getting Building Fund. Renovations were funded with further government money – £315,000 from the UK Shared Prosperity Fund and £90,000 from the HAZ. The market is operated by Little Blackpool Leisure which comprises Blackpool-born directors Andrew Shields and James Lucas, and locally based Jake Whittington.[73]

The HAZ cultural programme has included artist-led workshops and activities, and pop up creative markets.[74]

Tourism

editBlackpool's development as a tourist resort began in the second quarter of the 18th century when sea bathing started to become popular. By 1788, there were about 50 houses on the sea bank. Of these around six accommodated wealthy visitors while a number of other private dwellings lodged the "inferior class whose sole motive for visiting this airy region was health".[75] By the early 19th century, small purpose-built facilities began catering for a middle-class market, although substantial numbers of working people from manufacturing towns were "being drawn to Blackpool's charms".[76] The arrival of the railway in 1846 was the beginning of mass tourism for the town. In 1911, the town's Central Station was the busiest in the world, and in July 1936, 650 trains came and went in a single day.[77]

North Pier opened in 1863, designed by Eugenius Birch for Blackpool's "better classes", and always retained its unique qualities of being a quieter, more reflective place compared with Blackpool's other two piers.[78] The following half century included the construction of two further piers – South Pier (now Central Pier) in 1868 and Victoria (now South Pier) in 1893 – the Winter Gardens (1878), Blackpool Tower (1894) and the earliest surviving rides at Blackpool Pleasure Beach (founded in 1896).

Blackpool's Royal Palace Gardens at Raikes Hall was a world-famous destination for variety and music hall stars from the mid-18th century. It boasted a Grand Opera House, Indian Room for theatrical and variety performances, a Niagara café with cyclorama, a skating rink and fern house, an elaborate conservatory, monkey house, aviary and outside dancing platform for several thousand people. The gardens also had carriage drives and walkways with Grecian and Roman statues for promenaders to enjoy. There was also a boating lake and a racing track with grandstand for several thousand. More than 40,000 visitors passed through its gates during the opening week in 1872.[79]

Working-class tourists dominated the heart of the resort, which was the go-to destination for workers from the industrial north and their families. Entire towns would close down their industries during Wakes weeks between June to September, with a different town on holiday each week. Communities would travel to Blackpool together, first by charabanc and later by train.[80] But Blackpool still catered for a "significant middle-class market during the spring and autumn" favouring the residential area of North Shore.[76]

Work started in Blackpool on the UK's first electric public tramway on 24 February 1884 and the Blackpool Tramway officially opened on 29 September 1885.[81] Blackpool became one of the first towns to mark important civic events with illuminated tram-cars when five Corporation trams were decorated with coloured lights to mark the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1897.[82]

Electric lighting came to Blackpool in 1879 and 100,000 people congregated to see the promenade illuminated on the evening of 19 September. In May 1912 Princess Louise officially opened a new section of North Promenade – Princess Parade – and lights were erected to mark the occasion.[82] The First World War called a temporary halt to the display in 1914 but by 1925 the lights were back with giant animated tableaux being added and extending the Blackpool Illuminations to almost six miles from Squires Gate to Red Bank Road.

In 1897, Blackpool Corporation prohibited "phrenologists, "quack" doctors, palmists, mock auctions and cheap jacks" hawking on Blackpool sands. The outliers moved onto Central Promenade where they erected stalls in front gardens. The stretch became known as the Golden Mile and sideshows became one of its key features until the 1960s.[83]

In the 1920s and 1930s, Blackpool was Britain's most popular resort, which JB Priestley referred to as "the great, roaring, spangled beast".[76] It provided visitors with entertainment and accommodation on an industrial scale. At its height it hosted more than 10 million visitors a year and its entertainment venues could seat more than 60,000 people.[citation needed]

Blackpool remained a popular resort through much of the 20th century and, in contrast to most resorts, increased in size during World War II – remaining open while others closed and with many civil servants and military personnel sent to live and work there.[76]

Many seaside resorts fell from grace during the latter half of the 20th century as mobility, wealth, visitor aspirations and competition were in a state of flux, but Blackpool managed to retain its popular/working-class appeal as the "Las Vegas of the North".[84]

Despite economic restructuring, increased competition and other challenges, Blackpool continues to thrive as a visitor destination.[85] Tourism in the town supports 25,000 full-time equivalent jobs – one in five of the workforce. In 2023 the town was named the nation's best-value holiday destination. In 2021 18.8 million visitors contributed £1.5 billion to the local economy, making Blackpool the nation's biggest seaside resort.[77][86] In 2022 the resort attracted a further 1.5 million visitors – a total figure of 20.33 million, contributing £1.7bn to the local economy and supporting more than 22,000 jobs.[87]

Main tourist attractions

edit| Attraction | Opened | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| North Pier | 1863 | |

| Blackpool's first pier designed by the leading pier engineer Eugenius Birch. Its pierhead was enlarged to house the Indian Pavilion of 1800 and the pier was doubled in width in 1897. Today it houses The Joe Longthorne Theatre, five bars, amusements and rides including a Venetian carousel. | ||

| Central Pier | 1868 | |

| Designed by John Isaac Mawson for a more popular market than the North Pier, it was used for outdoor dancing originally, followed by roller skating and fairground rides in the mid-20th century. Today it has shops, bars, amusements, games and rides including a big wheel. | ||

| South Pier | 1893 | |

| Designed by T P Worthington and known as the Victoria Pier until 1930, it had an elaborate oriental-influenced pavilion by J D Harker,[76] shops, a bandstand and photograph stalls, and catered for more upmarket visitors. Today it has bars and food outlets, amusements and rides including a 38m bungee jump. | ||

| Winter Gardens | 1878 | |

| Originally boasting an exotic, glass-roofed Floral Hall for promenading, indoor and outdoor skating rinks, and the Pavilion Hall for special events. The following half century included the addition of the Empress Ballroom (1896), Olympia (1930), several themed rooms including the Spanish Hall (1931), and the Opera House (1939).[76] In 2022 the new Conference & Exhibition Centre was opened.[88] | ||

| Blackpool Tower | 1894 | |

| Inspired by the Eiffel Tower Blackpool Tower was the tallest manmade structure in the British Empire when built – 518 feet (158 metres). Dr. Cocker's Aquarium, Aviary and Menagerie had existed on the site from 1873 and was incorporated into the structure – replaced by the Tower Dungeons in 2011.[89] The Tower Circus is one of four circus arenas worldwide that features a water finale, with a ring floor which lowers to reveal 42,000 gallons of water. The Tower Pavilion opened in 1894 and was replaced by the Tower Ballroom in 1898. Today the Tower attractions are the Tower Eye, Ballroom, Circus, Dungeon, Fifth Floor entertainment suite and Dino Mini Golf. | ||

| Grand Theatre | 1894 | |

| Dubbed 'Matcham's masterpiece' the theatre has a flamboyant free Baroque exterior and lavish interiors.[76] The theatre opened with a production of Hamlet with Wilson Barrett in the starring role. The theatre closed in 1972 and reopened in 1981. Today it hosts a mix of popular and high culture shows including a programme of ballet each January. | ||

| Pleasure Beach | 1896 | |

| Founded in 1896 by W G Bean in an area populated by Romani Gypsies, the Pleasure Beach amusement park is still owned by Bean's descendants. Sir Hiram Maxim's Captive Flying Machine, a large rotated swing ride, was erected in 1904 and still survives today.[76] When it opened in 1994, The Big One was the tallest roller coaster in the world. In 2011 the park opened Nickelodeon Land. | ||

| Madame Tussauds | 1900 | |

| Louis Tussaud, the great-grandson of Marie Tussaud, moved to Blackpool in 1900 and opened waxworks in Blackpool in the basement of the Hippodrome Theatre, Church Street. In 1929 the Louis Tussaud's Waxworks opened on Central Promenade. It was closed in 2010 and re-opened as Madame Tussauds, operated by Merlin Entertainments, in 2011.[90] | ||

| Illuminations | 1912 | |

| Launched to celebrate the opening of Princess Parade on North Promenade, today the Illuminations stretch 6.2 miles (10 km) between Starr Gate and Bispham and use over one million bulbs. The illuminations usually ran for 66 nights during autumn but have been extended into the winter months since the Covid pandemic.[91] The lights are switched on annually by a celebrity, over the years including Jayne Mansfield, Gracie Fields, David Tennant, Tim Burton and Kermit the Frog. Lightworks is the illuminations depot where manufacture and maintenance of all of the Blackpool Illuminations takes place. It is not open to the public but operates occasional heritage tours. | ||

| Ripley's Believe it or Not | 1973 | |

| An American franchise, the 'odditorium' is based on the extensive collection of Robert Ripley (1890–1949). Ripley's was originally on the Golden Mile but moved close to the Pleasure Beach in 1991. Blackpool's collection includes animal oddities such as the two-headed calf and the world's smallest production car. | ||

| Blackpool Zoo | 1976 | |

| The zoo opened in 1972 on a site of the former Stanley Park Aerodrome and housed two Asian elephants, three white rhinos, two giraffes, sea lions, gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans, lions and two giant tortoises including Darwin, who died aged 105 in the year of the zoo's 50th anniversary, 2022.[92] Today it houses over 1,000 animals and includes a wolf enclosure. In 2023 it opened a new big cat enclosure and a new £100k facility for its Magellanic penguin colony.[93] In summer 2023 it welcomed its first critically endangered Bornean orangutan baby for more than two decades after first-time mother Jingga gave birth.[94] | ||

| Sandcastle Waterpark | 1986 | |

| The Sandcastle was built on the site of the former South Shore Open Air Baths, which opened in 1923 and were modelled on the Colosseum in Rome.[95] In 1986 it had two water slides and a wave pool as well as decorative flamingos, palm trees, terraces and a constant temperature of 84 degrees. It also had a nightclub.[96] Many original features remain but today it claims to be the UK's biggest indoor waterpark with 18 slides. | ||

| Sea Life | 1990 | |

| Located on Central Promenade and opened by First Leisure as the Sea Life Centre, the aquarium featured a transparent viewing "tunnel of fear" through a 500-million gallon tank holding ten species of predators.[97] Now operated by Merlin Entertainments, today it holds 2,500 aquatic creatures across 50 displays. | ||

| Peter Rabbit: Explore and Play | 2022 | |

| Operated by Merlin Entertainments, located on Central Promenade and based on Beatrix Potter's storybook character, the interactive multi-sensory family attraction features challenges in themed zones including Jeremy Fisher's Sensory Pond, Mr McGregor's Garden, The Burrow and Mr. Bouncer's Invention Workshop. | ||

| Gruffalo & Friends Clubhouse | 2023 | |

| Adapted from children's stories by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler, this attraction features play zones inspired by The Gruffalo, The Gruffalo's Child, Zog, The Snail and the Whale, Room on the Broom and The Highway Rat. | ||

| Showtown | 2024 | |

| Blackpool's museum of entertainment is due to open in March 2024. Exhibits will highlight Blackpool's entertainment heritage and include circus, shows, magic, Illuminations and dance. The museum will be on the first floor of the new Sands Venue Resort Hotel and Spa on Central Promenade. Items expected in the museum's collection are the famous bowler hat worn by Stan Laurel, a prop used by the comedic magician Tommy Cooper, and various mementos from the Tower Circus.[98] | ||

Fringe attractions

edit| Attraction | Opened in | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Golden Mile | 1897 | |

| The name given to the stretch of Promenade between the North and South piers. The promenade is actually 1.6 miles (2.6 kilometres) in length. It developed from traders who were prohibited from hawking on the sands and was home to sideshows until the 1960s.[83] Today it features many of the main attractions, including the Tower, as well as amusements and souvenir shops. | ||

| Pleasure Beach Arena | 1937 | |

| The oldest purpose-built ice theatre in the world,[99] it opened in 1937 as the Ice Drome. The rink was home to Blackpool Seagulls ice hockey team. The Hot Ice Show is performed here annually and the Arena is open to public skating. | ||

| The Casino | 1940 | |

| Built in 1913 in an oriental style reminiscent of continental casinos, the venue was never actually a casino but contained a restaurant, bar, shops, billiard tables and theatre.[76] Today it features the Paradise Room and Horseshoe theatres, which host regular magic shows and hypnotists as well as other variety shows. It also contains the White Tower restaurant. The 850-seat Globe Theatre, originally a custom-built circus,[100] was a later addition built next to the Casino. | ||

| Brooks Collectables | 1947 | |

| A family run collectables shop for three generations with free entry to their first floor museum on South Promenade. The museum features vintage toy collections and Blackpool memorabilia.[101] | ||

| Princess Parade Crazy Golf Course | 1957 | |

| Located in the seafront sunken garden near Blackpool North Pier, the course became derelict before reopening in 2021. The two-year restoration was funded by the National Lottery Community Fund and carried out by volunteers from the Fulfilling Lives programme, which supports people struggling with homelessness, substance abuse and mental health issues. There are two storyboards at either end of the course that document the history of the site going back to the 1700s.[102] | ||

| Model Village | 1972 | |

| Designed as a traditional Lancashire village, miniature buildings depict scenes of rural life across 2.5 acres of gardens attached to Stanley Park. | ||

| Coral Island | 1978 | |

| The largest of the town's many amusement arcades, built on the site of the former Blackpool Central railway station and covering two acres of land. | ||

| Funny Girls | 1994 | |

| A cabaret drag bar founded by Basil Newby, the venue initially opened on Queen Street and now occupies the Art Deco former Odeon cinema on Dixon Road. Choreographer Betty Legs Diamond and compere DJ Zoe are the original Funny Girls. In 2022 Ava King Cynosure became the first AFAB drag queen to become a resident performer.[103] | ||

| Pasaje Del Terror | 1998 | |

| An interactive walk-through horror attraction featuring scare actors in the basement of the Pleasure Beach Casino building. | ||

| Spitfire Visitor Centre | 2009 | |

| Based in Hangar 42 at Blackpool Airport, which was constructed in 1939 for the RAF, the collection here included five Spitfire replicas and a Hawker Hurricane MKI. Visitors can sit in the cockpit or operate a flight simulator. | ||

| Comedy Carpet | 2011 | |

| Constructed on the headland opposite Blackpool Tower, the 'carpet' is made of granite and concrete, and features catchphrases and jokes from hundreds of comedians, including Kenn Dodd, Frankie Howerd, Tommy Cooper and Morecambe and Wise.[104] | ||

| Viva Blackpool | 2012 | |

| Built on the site of the Alhambra Theatre and later Lewis's department store and Mecca Bingo, the cabaret showbar hosts a variety of year-round acts and shows. | ||

| Tramtown | 2015 | |

| Until 2011, the current heritage trams operated the main Blackpool tram service. After the multi-million pound upgrade put them out of service, plans were made to retain a core selection of trams from the original system and return them to passenger carrying duties.[105] The Heritage Tram Centre offers tours of tram sheds and engineering workshops as well as heritage tram journeys including an illuminated tour, a fish and chips tour and ghost tours. In 2023 it announced its vision for Tramtown – a tram heritage centre to be developed at the current depot.[1] | ||

| House of Secrets | 2021 | |

| The first dedicated family magic bar in Blackpool,[106] located in the historic Winter Gardens complex and owned by local magician Russ Brown. Brown formerly held residencies at Blackpool Tower and Blackpool Pleasure Beach, and compered and directed Blackpool Magic Convention – the world's largest – which takes place at the Winter Gardens each February.[107] | ||

| Hole in Wand | 2022 | |

| A wizard-themed golf course located in the former Woolworths building on Blackpool Promenade. The attraction is owned by the Potions Cauldron, which also operates a drink emporium and similar mini golf attraction in York.[108] | ||

| Arcade Club | 2022 | |

| A retro arcade on Bloomfield Road with over 200 games, including Pac Man, Space Invaders, Out Run, Time Crisis and pinball, plus modern games, such as House of the Dead 5, Luigi's Mansion, and sports such as air hockey and basketball.[109] | ||

Nature tourism

edit| Attraction | Opened in | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Beaches | N/a | |

| Blackpool boasts "seven miles of golden sands" which in 2016 were named the second best shoreline in the world and the best in the UK.[110] The same year Blackpool South beach was awarded Blue Flag status.[111] EU environmental protection laws are credited with the improvement of the beaches, which in the 1990s were covered in raw sewage and other waste.[112] Just six of 29 waters surveyed around the Blackpool region in 1988 met the EU's bathing water guidelines but, by 2014, all of the resort's beaches passed the EU test, after some £1bn was spent on clean water improvements.[113] In 2023 eight beaches on the Fylde Coast were awarded Seaside Awards by environmental charity Keep Britain Tidy, including Blackpool South, Blackpool Central and Bispham. However the Environment Agency classified the bathing water quality in Blackpool South as 'sufficient' in 2022, rather than 'good', as in the previous three years,[114] and 'poor' in Blackpool North rather than 'sufficient' or 'good', as in previous years.[115] On 12 June 2023 United Utilities discharged raw sewage into the sea from its water treatment plant in Fleetwood leading to 'no swim' warnings, which were lifted by the end of June.[116] | ||

| Stanley Park | 1926 | |

| A 260-acre park featuring a boating lake, Art Deco café, amphitheatre and bandstand, sports and recreational facilities, golf course and cricket club. To accommodate a growing population, in 1921 the Corporation of Blackpool commissioned T H Mawson to plan a comprehensive park and recreational centre. Stanley Park was opened on 2 October 1926 by Edward George Villiers Stanley – 17th Earl of Derby.[117] The Park is listed as Grade II* on the Historic England Register of Parks and Gardens and, along with surrounding streets, was designated a conservation area in January 1984. In 2005 a £5.5m Heritage Lottery Fund-aided programme of repair, conservation and enhancement was undertaken to help restore the park to its former glory.[118] In 2022 a new masterplan was developed for the park, which will celebrate its centenary in 2026.[119] In May 2022 a new skate park was opened after local skaters secured £200,000 of funding.[120] In 2023 facilities including the athletics track, tennis courts, football pitches and toilets were refurbished.[121][122][123][124] The park is maintained with support from the Friends of Stanley Park, who dedicate time to gardening, wildlife conservation, organising and hosting events including weekly live music at the bandstand throughout the summer.[125] The park has been voted the UK's favourite by the Fields in Trust three times – in 2017, 2019 and 2022.[126] | ||

Culture

editArt

editBlackpool Art Society was formed in 1884 by George Dearden as Blackpool Sketching Club. The first exhibition was at the YMCA Rooms in Church Street.[127] In 1886 the club hosted an exhibition of 226 exhibits in the Victoria Street schoolrooms. The Grundy brothers were prominent members, and in 1913 the society was granted the use of the new Grundy Art Gallery for its annual exhibition, where it still exhibits today.[127][better source needed]

Blackpool School of Arts, part of Blackpool and The Fylde College, opened in 1937 on Park Road in a building designed by civic architect JC Robinson. The building houses a gallery space which hosts a range of exhibitions. Alumni visual artists include Jeffrey Hammond, Adrian Wilson, Sarah Myerscough and Craig McDean.[128] Plans for a new town centre 'multiversity' are set to replace the current Park Road campus in 2026.[129]

The Grundy Art Gallery on Queen Street opened in 1911 and adjoins Blackpool Central Library.

Established in 2011 and named after its former use for the production of Blackpool rock, the Old Rock Factory consists of studios housing printmakers and other artists in Blackpool. Residents include printmaker and painter Suzanne Pinder[130] and its founder, screen printer Robin Ross who brought the building back into use.[131] Ross, a former radio DJ,[132] also founded Sand, Sea and Spray street art festival. Running between 2011 and 2016, the festival featured live street art by international artist produced on walls and billboards in various locations throughout central Blackpool.[133]

Opened in 2014, Abingdon Studios is a contemporary visual art project space and artist studios curated and directed by Garth Gratrix. Gratrix, who has curated the Robert Walters Group UK Young Artist of the Year, champions working-class and queer artists.[134][135] In 2021 he and artist Harry Clayton-Wright produced We're Still Here, the first permanent collection of LGBTQIA+ heritage in Blackpool, supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.[136]

Co-founder and directed by local artists Dawn Mander and Kate Yates, HIVEArts is a gallery space and grassroots arts collective that hosts regular exhibitions.[137] Exhibitions have included The Art Of Forgery by Peter Sinclair (2022),[138] the Gallery Space open exhibition (2022) and The Air That A Breathe, a group exhibition raising money for the Aspergillosis Trust (2023).[139] In 2022 the gallery hosted an art auction of 250 original paintings, photos and sculptures donated by local artists raising £8,000+to help victims of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[140]

Tea Amantes is a tearoom and gallery run by Anna Paprzycka. Established in 2021 the gallery hosts monthly art exhibitions by local emerging artists.[141] Exhibitions have included The Main Resort, featuring Blackpool street photography,[142] and Golden Energies by Katarzyna Nowak.[143]

Left Coast

editThis section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (November 2023) |

Left Coast is an arts organisation that was established in 2013, as part of the UK Creative People and Places Programme. It aims to produce socially-engaged creative and cultural activities in Blackpool and Wyre.[144]

Left Coast projects have included the National Community Lottery funded Real Estates programme which aimed to "decrease social isolation and increase personal and community agency through the development of collaborative arts-based activities in three residential areas of Blackpool and Fleetwood".[144] Artists were given residencies on local housing association estates to test whether they could become embedded in the community rather than being seen as visitors. An independent evaluation based on findings by UCLan stated that the project "made a real difference to local communities through the use of arts as a catalyst for the development of a sense of confidence and self-worth, developing or rediscovering skills, and increasing social connections."[144]

Following the publication of a Financial Times article Left Behind: Can anyone save the towns the economy forgot?[145] in 2017, Left Coast commissioned a series of artists to respond to the article with the intention of providing "a nuanced and thoughtful counter position". Photographer Craig Easton photographed the Williams family who he had first met in 1992 for a commission by French newspaper Libération to document the British 'underclass'. His images of the Williams's "came to symbolise the deprivation that was a legacy of the Conservative government of the day". Revisiting them for Left Coast, Easton created a project entitled Thatcher's Children.[146]

Left Coast raised £1.3m towards the Art B&B project from funding sources including the Coastal Communities Fund and Arts Council England, Community Business Fund, Tudor Trust and the Clore Duffield Prize Fund.[147] Opened in 2019, the B&B included 18 different themed rooms curated by UK artists. The Now You See it, Now You Don't suite was created by artist and writer professor Tim Etchells and the Willy Little suite by artist Mel Brimfield celebrated the career of a fictional entertainer and his performances at The Ocean Hotel – the original name of Art B&B.[148] Despite receiving £73,000 from the government's Culture Recovery Fund during the COVID-19 pandemic, the B&B closed in October 2022 claiming there were not enough future bookings to sustain the business.[147] Left Coast clarified it was no longer involved with the project which had become an independent Community interest company.[149]

In 2022, Left Coast opened Wash Your Words: Langdale Library & Laundry Room on social housing estate Mereside. It was designed by Lee Ivett and Ecaterina Stefanescu following conversations with the community about their needs. It provides somewhere for people to wash clothes, read, learn and create art and cost £30,000 to renovate. In January 2023 it was nominated for the RIBA Journal MacEwen Award, celebrating architecture for the common good. Judges praised it for a "joyful design [that] raises expectations of the quality of architecture people should demand of social housing estates, changing the conversation from what people don't have, to what community asset models should look like from a social, economic and environmental perspective".[150][151]

Aunty Social

editEstablished in 2011, Aunty Social is a voluntary-run community arts organisation in Topping Street.[152] It is co-founded and directed by Catherine Mugonyi, a member of the National Lottery Heritage Fund North Committee and former Clore Fellow. In 2013 it registered as a Community interest company (CIC) and opened Charabanc, a shop selling products made by local artists and designers.[153] Aunty Social runs projects including online arts and culture magazine Blackpool Social Club, the Winter Gardens Film Festival and BFI Film Club. Facilities include a community darkroom and library. A Queer Craft Club and Heritage Craft workshops are hosted.

Local textiles group Knittaz With Attitude is an Aunty Social project which has carried out several yarn bombing projects in public spaces. In 2022 the group responded to reports of sexual harassment recorded by Reclaim Blackpool which maps incidents that take place in public places. Over 20 participants created craftivist works highlighting the precarious safety of women and using methods including cross stitch, crochet, appliqué and embroidery under the banner We're Sew Done. The pieces were placed in locations plotted on the map before being exhibited in Blackpool Central Library. The exhibition featured in local singer Rae Morris's video for her single No Woman Is An Island.[154]

Public art

edit| Name of artwork | Dates | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Medici Lions |

|

|

| A pair of lions modelled on the Medici Lions in Rome stand in Stanley Park. The original lead lions were made in 1790 and sold in 1922 to John Magee who gifted them to Blackpool Corporation. They were removed in 2013 and loaned to Stowe House, where they originally stood. Replicas were installed in the park in 2013.[155] Stanley Park also features a number of nature-inspired sculptures in its Italian Gardens, and We Love You To The Moon, a stone carving memorial to Jane Tweedle from Blackpool who was killed in the Manchester Arena bombing in 2017.[156] A statue of Charlie Cairoli was installed in the Rose Garden in 2008 but was later moved to Blackpool Tower and replaced with a plaque.[157] | ||

| Ballet Dancers | Installed in the 1990s | |

| Designed by artists Phil Bew and Diane Gorvin, two bronze ballet dancers standing on stainless steel plinths at either end of Clifton Street in the town centre.[155] | ||

| Great Promenade Show | Commissioned from 2001 to 2005 | They Shoot Horses, Don't They |

| A collection of 10 artworks commissioned over a period of four years from 2001 to 2005 forming an 'outdoor' contemporary art gallery along 2 km of New South Promenade from Squires Gate to South Pier.[155] Some of the artworks have since been removed, including the High Tide Organ by Liam Curtin and John Gooding, which made music from the swell of the tide.[158] Alluding to the town's ballroom culture, They Shoot Horses, Don't They is a giant mirror ball by artist Michael Trainor. At six metres in diameter and weighing six tonnes it was the world's largest dance hall mirror ball at the time, covered in 47,000 mirrors that gently rotate and catch the light.[159] | ||

| Choir Loft | Installed in 2008 | |

| Located next to the Cenotaph war memorial, artist Ruth Barker's work consists of letters carved into granite blocks and treated with gold leaf reading 'Sing softly. Be still. Cease'. The memorial is dedicated 'to those who struggle for freedom in all conflicts, and those who remember them'.[160] | ||

| The Wave | Installed in 2009 | |

| Installed in St John's Square and designed by Lucy Glendining the 10.5m high x 2.5m wide stainless steel wave structure has internal lighting that shines through a laser cut pattern with transparent blue resin insets. It features a resin swimmer figure in clear blue and resin blue pebble sculptures at the base which act as seats.[155] | ||

| Soldier Sculpture (and Salisbury Woodlands) | Installed in 2009 | |

| Designed by Thompson Dagnall in Salisbury Woodlands, the figure of a soldier with metal helmet and rifle is carved from Lancashire Mill stone and sits atop a WWII pillbox. The woodlands also house a number of wooden carved sculptures including an archway entrance carvings of a bat, wood pecker and leaves.[155] | ||

| Sand Sea & Spray | ||

| A number of large scale graffiti artworks feature throughout the town in locations including Talbot Road, Cookson Street and Palatine Road.[155] They were created by a number of international artists as part of Sand, Sea & Spray street art festival which ran between 2011 and 2016.[161] | ||

| The 999 statue | Installed in 2013 | |

| A 2.5m monument by Matt Titherington installed at Jubilee Gardens to honour police officers and a member of the public who died trying to rescue a man who had gone into the sea to save his dog in 1983.[162] | ||

| Lightpool | Started in 2016 | |

| Lightpool is an annual light festival held over October half term that sees artistic light installations throughout the town centre and various fringe events. It was awarded the Arts Council's National Portfolio Organisation status for 2023–2026, securing funding worth nearly £700,000.[163] | ||

| Fancie Benches |

|

|

| Artist Tina Dempsey installed her first Fancie Bench in Blackpool's King's Square and a second bench was installed in Edward Street. Fabricated by Lightworks – Blackpool Illuminations Depot – out of fibreglass, the colourful abstract designs were part of the Quality Corridors Scheme to improve the appearance of key streets in the town.[164] | ||

| Tram Benches | Installed in: 2020 | |

| Part of the Quality Corridors Scheme, artist Andy Hazell installed two stainless steel benches in the shape of trams in Talbot Square. They depict heritage trams – a Blackpool OMO, built in the mid-1930s, and the Brush, built originally in 1937.[165] | ||

| The Call of the Sea | Installed in 2021 | |

| A life-sized bronze painted sculpture by artist Laurence Payot in Talbot Square. It was designed in consultations with fashion students from Blackpool and The Fylde College, pupils from Blackpool Gateway Academy and the council's beach patrol team, and was modelled after a local girl. It cost £35,000, funded by the Quality Corridors Scheme.[166] | ||

| Storytrails: Queercoaster | Created in 2022 | |

| By Joseph Doubtfire, as part of the government-funded Unboxed festival. An augmented reality walking tour, it allowed participants to experience and learn about queer history in Blackpool through fragments of archive footage of news reports and stories collected from locals.[167] | ||

| Blackpool Stands Between Us and Revolution | Installed in 2022 | |

| An illuminated text-based artwork by Tom Ireland that was temporarily on the roof of the Grundy Art Gallery. It is based on a quote by a local businessman to architect Thomas H Mawson in the 1920s to explain the town's importance to working-class people.[168] | ||

Performing arts

editTheatre

editAt its peak in the 1930s Blackpool's numerous theatres and cinemas could seat more than 60,000 people.[76]

The Theatre Royal on Clifton Street first opened as the Assembly Rooms and Arcade in 1868. It later became the Tivoli Electric Theatre and eventually Yates's Wine Lodge before it was destroyed by fire in 2009.[169][170]

In 1874 the Indian Pavilion was built on North Pier to host regular concert performances. After being damaged by fire in 1921 and destroyed by another in 1938[171] it was replaced by the Art Deco Pavilion Theatre (now the Joe Longthorne Theatre) in 1939. One of few remaining pier theatres in the country, it hosts variety acts during the summer season. The theatre is Grade II listed but has been on the Theatres At Risk Register since 2014.[172]

The Borough Theatre (later Queens Theatre) opened in September 1877 on Bank Hey Street. A blue Plaque marks the location of the building which was demolished in 1972/73.[173]

Her Majesty's Opera House, part of the Winter Gardens complex, was built in 1889 and designed by architect Frank Matcham.[174] The 2,500 capacity was soon deemed insufficient and was redesigned by architects Mangnall and Littlewood in 1910. In October 1938 the old Opera House was demolished and the third and current Opera House, with a classic Art Deco design, replaced it. Seating 3,000, it was the largest theatre in the country when it opened.[76] The first Royal Variety Performance to be held outside London was staged there in 1955.[175] The Opera House is one of only three remaining historic theatres in Blackpool still in operation, regularly staging touring musicals.[176][177]

The Empire Theatre and Opera House on Church Street opened in 1895 and by 1900 it had been converted into a circus venue and renamed Hippodrome. In 1929 it became the ABC cinema but continued to host stage shows, including in the 1960s TV variety show Blackpool Night Out in which the Beatles appeared on 19 July 1964. The theatre became The Syndicate superclub in 2002 until it was demolished in 2014.[178]

The Prince of Wales Theatre was built in 1879 next to the site of Blackpool Tower. It was replaced in 1900 with the grand Alhambra complex but, unable to compete with the neighbouring Tower hit financial difficulties in 1902. Architect Frank Matcham remodelled the building and it became the Palace Theatre in 1904. It was demolished in 1961.[179]

The Grand Theatre was built in 1894 and dubbed Frank Matcham's masterpiece.[76] It hosts a mix of local, mainstream and high brow performances as well as an annual pantomime.[180] In the 1990s the theatre was annexed to provided a Studio Theatre.[181] Supported by the Friends of the Grand Theatre, it is a registered charity and in 2022 received Arts Council England National Portfolio Organisation status – a three-year investment of more than £1.5m.[182] In September 2023 Blackpool Council committed £500,000 to carry out urgent repairs to the theatre.[183] The Grand has had a youth theatre company since 1996[184] and has partnered with the Royal Shakespeare Company to engage school children with theatre and performance.[185]

The Old Electric is Blackpool's newest theatre, opening in 2021 on Springfield Road in the former Princess Electric Cinema. Founded by creative director Melanie Whitehead, it became the home of The Electric Sunshine Project CIC, a community theatre company she established in 2016, as well as a community arts space. The renovation of the building, which had been a string of nightclubs prior, was National Lottery funded and carried out during lockdown.[186]

Dance

editDance has been central to Blackpool culture for 150 years. One of the first places visitors could dance was on the open air on the piers and its popularity led to ballrooms opening across the town. The Tower Ballroom came first in 1894, quickly followed by the Empress Ballroom and the Alhambra.[187]

The original Tower Ballroom was a smaller pavilion but the facility posed a threat to the Winter Gardens whose management responded in 1896 by improving its facilities. The Empress Ballroom – much grander and larger than its rival – was built on the site of a roller rink and designed by Mangnall and Littlewood with a capacity of 3,000.[76] Towards the end of the First World War, in 1918, the Empress Ballroom was taken over by the Admiralty as a space to assemble Gas Envelopes for their R33 Airship. Renovations in 1934 included a new sprung dance floor with 10,000 strips of oak, mahogany, walnut, and greenwood, on top of 1,320 four inch springs, covering 12,500 foot.

The first Blackpool Dance Festival was held in the Empress Ballroom during Easter week in 1920. The idea is credited to either Harry Wood, the musical director of the Winter Gardens, or Nelson Sharples, a music publisher in Blackpool.[188] The festival was devoted to three competitions to find three new sequence dances in three tempos – waltz, two step and foxtrot. There was one competition per day and, on the fourth, one dance was chosen as the winner. In 1931 the dance festival hosted the inaugural British Professional and Amateur Ballroom Championships and in 1953 the competitions included the North of England Amateur and Professional Championships, a Ballroom Formation Dancing Competition, the British Amateur and Professional Ballroom Championships, plus a Professional Exhibition Dancing Competition. In 1961, a British Amateur Latin American Tournament was held, followed by a Professional event in 1962. These two events were upgraded to Championship status in 1964. 1968 saw the introduction of the Professional Invitation Team Match and in 1975 the first British Closed Dance Festival was held – now the British National Championships. In modern times around 50 countries are represented across eight annual festivals in the Empress Ballroom and Blackpool Dance Festival is considered ‘the world's first and foremost festival of dancing’.[188]

The present Tower Ballroom was designed by Frank Matcham and opened in 1899 to rival the Empress Ballroom, matching its capacity of 3,000. Its sprung dance floor measures 120 feet by 102 feet and consists of 30,602 separate blocks of mahogany, oak and walnut. The inscription above the Ballroom stage, 'Bid me discourse, I will enchant thine ear', is from Shakespeare's Venus and Adonis sonnet. Among the Ballroom's one-time strict rules were 'gentlemen may not dance unless with a lady' and 'disorderly conduct means immediate expulsion'. Originally, dancing was not permitted on Sundays when an evening of sacred music was performed instead. In December 1956, the ballroom was badly damaged by fire and the dance floor was destroyed. It took two years and £500,000 to restore.[189] The BBC series Come Dancing – aired between 1950 and 1998 – was broadcast from the Tower Ballroom and featured professional dancers competing against each other. Its reinvention as Strictly Come Dancing launched in 2004 and includes an annual Blackpool week, when the show is broadcast from the Tower Ballroom.[190] The Tower Ballroom remains a popular venue for dancing and its celebrated Wurlitzer organ still rises from below the stage.[76] In 2022 it featuring on the BBC's interactive map of 100 Places for 100 Years of the BBC.[191]

During the 20th century, ballroom bandleaders created new novelty dances including The Blackpool Walk, the dance craze of the 1938 summer season. The music was composed by Lawrence Wright, a prominent music publisher, under the pen name Horatio Nicholls, and choreographed by 1937 Blackpool Dance Festival Champions, Cyril Farmer and Adela Roscoe. Inspired by the Blackpool Walk, in 2020 local dance company House of Wingz created a new social dance, The Blackpool Way, as part of a community project called Get Dancing. Music was composed by Callum Harvey and dance steps and moves were submitted by people from across the world.[187]

Based on Back Reeds Road, House of Wingz was founded by married couple Samantha and Aishley Docherty Bell. Using knowledge and education in hip hop culture, the company aims to create a legacy or 'scene' for dance artists and musicians in Blackpool, who will contribute to a growing cultural landscape in the town.[192] House of Wingz is the Blackpool partner for Breakin' Convention, a festival celebrating the best in UK hip hop talent founded by pioneer Jonzi D.[193] In 2022 members of House of Wingz collected seven trophies in the UDO World Street Dance Championships including two first place prizes.[194] Although dance is at the heart of House of Wingz, it is also home to a collective of musicians, artists and performers who stage their own productions and collaborate on creative projects.[195] Skool of Street is House of Wingz' charitable arm, providing free access to classes for children who do not have the means to pay as well as delivering the Government's Holiday Activities and Food programme.[196]

Other dance schools in Blackpool include Phil Winstone's Theatreworks, Whittaker Dance & Drama Centre and Langley Dance Centre.

Amateur dramatics

editThere are a number of notable amateur and community theatre companies in Blackpool.

Junction Four Productions, formed in 1904 as Lytham Amateur Operatic Society (LAOS), is one of the original musical theatre groups on the Fylde Coast. A registered charity, it changed its name in 2018 to reflect its varied canon.[197] Blackpool & Fylde Light Opera Company (BFLOC) is an amateur musical comedy society that has hosted annual productions since 1950. [198] Blackpool Operatic Players (BOP) has been presenting musical theatre productions in Blackpool and the surrounding areas since 1953.[199]

On 14 January 2022, a blue plaque was unveiled on Michael Hall Theatre School (formerly Marton Parish Church Hall) on Preston New Road recording that, from 1930 to 2002, Marton Operatic Society performed Gilbert and Sullivan and other operas there.[200] Founded as Marton Parish Church Choral and Operatic Society in 1930 by Reverend Charles Macready and William Hogarth, their first production was Cupid and the Ogre. In 2021, following a decline exacerbated by COVID-19, members voted to wind the society up. A final concert version of The Mikado was held on 29 October.[201][202]

Michael Hall Theatre School is a small theatre space and school in the former Marton Parish Church Hall. Founded in 2003, it is run by Michael Hall who studied at the Royal Academy of Music and whose past pupils include Jodie Prenger and Aiden Grimshaw.[203] Hall also runs Musica Lirica Opera Company which aims to make opera accessible.[204]

Founded in 2005, TramShed is an inclusive theatre company and charity offering inclusive performing arts to all children, young people and adults many of whom have additional needs. In 2021 it was named a National Diversity Awards finalist.[205] Cou-Cou Theatre Productions is a Community Interest Company founded in 2018 by sisters Sophie and Nikita Coulon.[206]

Music

editHeritage

editBlackpool has a rich musical heritage associated with its tourist industry alongside a number of popular music scenes and artists that have emerged there. The first registered venue offering musical entertainment in Blackpool was the original Uncle Tom's Cabin, situated on the cliffs at North Shore, from the early 1860s.[207]

The Wurlitzer organ at Blackpool Tower Ballroom was played by Reginald Dixon from March 1930 until March 1970, with live broadcasts of his performances being aired each week during the summer season on the BBC Light Programme.[208] Phil Kalsall has been principle organist at the venue since 1977.[209]

Lawrence Wright was a successful music publisher and songwriter who moved to Blackpool in the 1920s and opened 20 song booths, hiring musicians to play his sheet music inside which passers-by would purchase after entering to listen and sing along.[210]

Blackpool was instrumental in the music of big bands who performed jazz and swing music in its dancehalls and ballrooms from the 1930s-1950s. Frequent performers from 1946 to 1959 were Ted Heath, Joe Loss and Jack Parnell.[211]

In the post-war period Blackpool was the centre of live entertainment outside London and there was a proliferation of musical talent coming from and discovered in the town. The town hosted three or four variety shows per night during tourist seasons, each featuring popular music including The Shadows, Tom Jones, Engelbert Humperdinck and American stars including Frank Sinatra who performed twice in the early 1950s.[212]

The heyday of Blackpool's musical history to date and the golden era was the 1960s when live music was offered in the town's many pubs, clubs, theatres and concert venues to accommodate its millions of visitors.[207] All the top British beat groups played in Blackpool, forging a tradition at the Winter Gardens Empress Ballroom of staging of rock, alternative and indie music with visiting bands through the decades including Queen, the Stone Roses, Blur and New Order.[212]

Smaller music venues of note include The Galleon bar on Adelaide Street which opened in 1954 and was a magnet for musicians[213] and Mama & Papa Jenks on Talbot Road, which attracted emerging acts of the 1970s including the Eurythmics and the Buzzcocks and evolved into a punk music venue hosting bands such as the Fits and the Membranes.[207]

John Lennon spent a short time living in Blackpool as a child and would often visit family there and watch musical acts including George Formby and Dickie Valentine.[214] The Beatles were booked to perform on South Pier throughout the summer of 1962 but their fame saw them outgrow the venue before they could fulfil their residency. They did go on to play a series of dates in the ABC Theatre and later the Opera House in August 1963 and 1964.[207]

The Rolling Stones gig at the Empress Ballroom on 24 July 1964 resulted in a riot. The venue was left badly damaged, with fans smashing two chandeliers, tearing up seats and breaking a Steinway grand piano. Two people were hospitalised and around 50 treated for minor injuries. Blackpool Council banned the Rolling Stones from performing in the town again, lifting the ban 44 years later, although the band is yet to return.[207]

Jimi Hendrix supported Cat Stevens at the Odeon complex on 15 April 1967. There are claims Hendrix was refused entry to his hotel after the show due to intoxication. Pink Floyd played the Empress Ballroom a month later, on 26 May 1967. Hendrix and Pink Floyd both returned later that year to perform on the same bill at Blackpool Opera House on 25 November 1967. Pink Floyd returned to Blackpool on 21 March 1969 to play the Blackpool Technical College Arts Ball on 21 March 1969.[207][215]

Factory Records' Section 25 formed in Blackpool in 1977. Their key recordings include the US crossover club hit Looking Form a Hilltop and the album From the Hip.[216] Another Blackpool band signed to the label was Tunnelvision, who recorded just one single for the label in 1981.[217]

Inspired by Blackpool

editThe large number of musical artists connected to Blackpool exceeds that of the town's comparable size[212] and include the band Boston Manor, Chris Lowe, Graham Nash, John Evan, John Robb, Jon Gomm, Karima Francis, Rae Morris, Robert Smith and Section 25. With the exception of grime artists, however, their hometown hardly features in the work of these artists and we never heard about ‘Blackpool sound’, as opposed to the Mersey Sound or Madchester.[212]

Blackpool has been referenced within popular music for the best part of a century.[218] Stanley Holloway’s 1932 comic song The Lion and Albert tells the story of a small child being eaten by a lion at Blackpool Zoo and George Formby, one of the town's most successful regular performers in the 1930s and ‘40s, penned songs including Blackpool Prom, Sitting on the Top of Blackpool Tower and With My Little Stick of Blackpool Rock.[218] The George Formby Society formed at the Imperial Hotel with 56 members a few months after Formby's death in 1961. Now consisting of over 800 members worldwide, many return to the same hotel quarterly to for society conventions.[219]

In the latter part of the 20th century songs inspired by Blackpool included, Blur’s This Is a Low, Soft Cell's Say Hello, Wave Goodbye, Manic Street Preachers' Elvis Impersonator, Blackpool Pier and The Kinks’ Autumn Almanac, which has been called ‘the most British song of all time’.[212]

Up The Pool by Jethro Tull, who formed as a blues-based rock band in the Blackpool in the late 1960s, was released in 1971. It differs from the band's other musical output at the time with frontman Ian Anderson, who lived in Blackpool, choosing to reflect national identity both lyrically and musically in a conscious rejection of the American music that influenced so many other British bands of the era. In Blackpool Tower Suite, Manchester indie band World of Twist present a personification of the Tower almost as a female deity presiding over the pleasure grounds of Blackpool.[218]