The bass saxophone is one of the lowest-pitched members of the saxophone family—larger and lower than the more common baritone saxophone. It was likely the first type of saxophone built by Adolphe Sax, as first observed by Berlioz in 1842.[1] It is a transposing instrument pitched in B♭, an octave below the tenor saxophone and a perfect fourth below the baritone saxophone. A bass saxophone in C, intended for orchestral use, was included in Adolphe Sax's patent, but few known examples were built. The bass saxophone is not a commonly used instrument, but it is heard on some 1920s jazz recordings, in free jazz, in saxophone choirs and sextets, and occasionally in concert bands and rock music.

| |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Single-reed |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 422.212-71 (Single-reed aerophone with keys) |

| Inventor(s) | Adolphe Sax |

| Developed | 1840s |

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

|

Sizes:

Orchestral saxophones: Specialty saxophones: | |

| Musicians | |

| See list of saxophonists | |

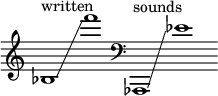

Music for bass saxophone is written in treble clef, just as for the other saxophones, with the pitches sounding two octaves and a major second lower than written. As with most other members of the saxophone family, the lowest written note is the B♭ below the staff—in the bass's case, sounding as a concert A♭1 . German wind instrument maker Benedikt Eppelsheim and Brazilian low saxophone maker J'Elle Stainer have both made bass saxophones with an additional key to produce low (written) A. This is similar to the low A key on the baritone saxophone, and produces a concert G1 (~ 49 Hz). Most basses made before the 1980s were keyed to high Eb, but most more recent models are keyed to high F#.

In jazz

editThe bass saxophone enjoyed some popularity in jazz combos and dance bands between World War I and World War II, primarily providing bass line, although bass sax players occasionally took melodic solos. Notable players of this era include Billy Fowler, Coleman Hawkins, Otto Hardwicke (of the Duke Ellington orchestra), Adrian Rollini (who was a pioneer of bass sax solos in the 1920s and 30s), Min Leibrook, Spencer Clark, Charlie Ventura, and Vern Brown of the Six Brown Brothers.[2] Sheet music of the period shows many bands photographed with a bass sax. The bass sax virtually disappeared in the 1930s, possibly due to its size, mechanical complexity, and high price. The invention of the electric bass guitar in the 1950s and its quick rise to popularity reduced demand for other bass instruments in popular music and other contemporary music.

American bandleader Boyd Raeburn (1913–1966) led an avant-garde big band in the 1940s and sometimes played the bass saxophone. In Britain, Oscar Rabin played it in his own band. Harry Gold, a member of Rabin's band, played bass saxophone in his own band, Pieces of Eight. American bandleader Stan Kenton's "Mellophonium Band" (1960–1963) featured fourteen brass players and used a saxophone section of one alto, two tenors, baritone, and bass on many Grammy winning compositions by Johnny Richards (with Joel Kaye doubling baritone and bass saxophones).[3] The Lawrence Welk Band featured Bill Page soloing on bass saxophone on several broadcasts during the 1960s. Shorty Rogers's Swingin' Nutcracker (recorded for RCA Victor in 1960) featured a bass saxophone (played by Bill Hood) on four of the movements.

One notable bass saxophonist performing today in the 1920s–1930s style is Vince Giordano. Jazz players using the instrument in a more contemporary style include Roscoe Mitchell, Anthony Braxton, Peter Brötzmann, J. D. Parran, Hamiet Bluiett, James Carter, Stefan Zeniuk, Michael Marcus, Vinny Golia, Joseph Jarman, Brian Landrus, Urs Leimgruber, and Scott Robinson, although none of these players use it as their primary instrument.

Jan Garbarek plays a bass sax on the 1973 album Red Lanta.

In rock

editBass saxophonists in rock include:

- Angelo Moore of the American band Fishbone

- Rodney Slater in the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band (1960s)

- Ralph Carney of the avant-garde rock band Tin Huey (1970s)

- John Linnell of They Might Be Giants (formed 1982)

- Dana Colley of Morphine (formed 1989)

- Kurt McGettrick in Frank Zappa's band in the late 1980s

- Alto Reed of Bob Seger and the Silver Bullet Band often played bass sax at live shows, in songs without a prominent sax part.

- Colin Stetson has performed and recorded with Arcade Fire, Bell Orchestre, Tom Waits, TV on the Radio, Bon Iver, Feist and LCD Soundsystem. He also performs and records his own compositions.

- Blaise Garza – touring member of Violent Femmes since 2004.

- Kellie Everett – member of The Hooten Hallers since 2014.

- Michael Wilbur - member of Moon Hooch

In classical music

editAt the 1844 World's Fair in Paris, the saxophone's premier performance was a chamber piece called Chant Sacré composed by Hector Berlioz for two trumpets, one soprano saxhorn, two clarinets, and one bass saxophone; Adolphe Sax himself played the saxophone part. The same year, Georges Kastner wrote for it in his opera Le Dernier Roi de Juda.

It is rarely used in orchestral music, though several examples exist. The earliest extant orchestral work to employ it is William Henry Fry's "sacred symphony" Hagar In the Wilderness (1853), which also calls for soprano saxophone and was written for Louis-Antoine Jullien's orchestra during its American tour. Richard Strauss, in his Sinfonia Domestica, wrote four saxophone parts including one for bass saxophone in C. Arnold Schoenberg wrote for the bass saxophone in his one-act opera Von Heute auf Morgen, and Karlheinz Stockhausen includes a part for it in the saxophone section of Lucifer's Dance, the third scene of Samstag aus Licht.[4]

In the 1950s and 1960s it enjoyed a brief vogue in orchestrations for musical theater: Leonard Bernstein’s original score for West Side Story includes bass saxophone, as does Meredith Willson’s Music Man and Sandy Wilson’s The Boy Friend.

The bass saxophone is occasionally called for in concert bands, typically in arrangements from before 1950. Australian composer Percy Grainger and American composer Warren Benson are particularly notable composers who wrote for it.

Today, bass saxophone is most commonly used to perform chamber music. It is typically featured in saxophone choirs and sextets, especially those in the direct legacy of teacher-soloist Sigurd Rascher.[citation needed] It is also occasionally used to perform in smaller (less than six-member) chamber groups, though typically to play a part originally intended for another instrument as very few such pieces are written to include bass sax.

References

edit- ^ Cottrell 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Cottrell 2012, p. 147.

- ^ Corey, Wayne (18 September 2012). "Stan Kenton's Mellophonium Sound Reborn: Kenton Alum Joel Kaye revives a '60s sound". JazzTimes.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ Cohen, Paul (January–February 1990). "Vintage Saxophones Revisited: An Historical Celebration Of The Bass Saxophone". Saxophone Journal. 14 (4): 8–12.

Bibliography

edit- Cottrell, Stephen (2012). The Saxophone. Yale Musical Instrument Series. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300100-41-9.

Further reading

edit- Rollini, Adrian (December 1928). "The When, Why, and How of the Bass Saxophone". Melody Maker. Vol. 3, no. 36. pp. 1365–1366.

- "Selecting the Instrument". Melody Maker. Vol. 4, no. 37. January 1929. p. 83.

- "Mouthpiece Methods". Melody Maker. Vol. 4, no. 38. February 1929. pp. 173, 175.

- "Mainly About Reeds". Melody Maker. Vol. 4, no. 40. April 1929. p. 393.

- "Tone Production". Melody Maker. Vol. 4, no. 41. May 1929. pp. 501–502.

- "The Problem of Transposition". Melody Maker. Vol. 42, no. 42. June 1929. p. 587.

- "Playing Bass Parts". Melody Maker. Vol. 4, no. 43. July 1929. pp. 679, 681.

- "Breaks―Their Phrasing And Accentuation". Melody Maker. Vol. 4, no. 44. August 1929. pp. 783–784.

- "Solo Choruses: A Few Pointers". Melody Maker. Vol. 4, no. 45. September 1929. pp. 875–876.

External links

edit- Media related to Bass saxophones at Wikimedia Commons