Alexander Raban Waugh (8 July 1898 – 3 September 1981) was a British novelist, the elder brother of the better-known Evelyn Waugh, uncle of Auberon Waugh and son of Arthur Waugh, author, literary critic and publisher. His first wife was Barbara Jacobs (1900-1996), daughter of the writer William Wymark Jacobs, his second wife was Joan Chirnside (1902-1969), and his third wife was Virginia Sorenson (1912-1991), author of the Newbery Medal-winning Miracles on Maple Hill.

Alec Waugh | |

|---|---|

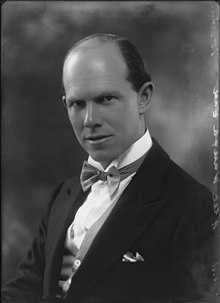

Alec Waugh in 1931 | |

| Born | Alexander Raban Waugh 8 July 1898 London, England |

| Died | 3 September 1981 (aged 83) |

| Resting place | St John-at-Hampstead |

| Education | Sherborne School |

| Spouses | Barbara Jacobs

(m. 1919; div. 1923)Joan Chirnside

(m. 1932; died 1969) |

| Children | Andrew Alexander Waugh (1933-2006) Veronica Waugh (b. 1934) Peter Raban Waugh (1938-2014) |

| Parent(s) | Arthur Waugh Catherine Charlotte Raban (1870-1954) |

Biography

editWaugh was born in London to Arthur Waugh (1866-1943) and Catherine Charlotte Raban, a great-granddaughter of Lord Cockburn (1779–1854). Another distinguished ancestor was his great-great-grandfather William Morgan FRS (1750–1833), a pioneer of actuarial science who served The Equitable Life Assurance Society for 56 years and who won the Copley Medal in 1789.[1] Among ancestors bearing the Waugh name, the Rev. Alexander Waugh D.D. (1754–1827) was a minister in the Secession Church of Scotland who helped found the London Missionary Society and was one of the leading Nonconformist preachers of his day.[2] His grandson Alexander Waugh (1840–1906) was a country medical practitioner, who bullied his wife and children and became known in the Waugh family as "the Brute". The elder of Alexander's two sons, born in 1866, was Alec's father, Arthur.[3]

Alec was educated at Sherborne School, a public school in Dorset. The result of his experiences was his first, semi-autobiographical novel, The Loom of Youth (July 1917), in which he dramatised his schooldays. The book was inspired by Arnold Lunn's The Harrovians, published in 1913 and discussed at some length in The Loom of Youth.[4]

The Loom of Youth was so controversial at the time (it mentioned homosexual relationships between boys, albeit in a very understated, staid fashion) that Waugh remains the only former pupil to be dismissed from the old boys' society (The Old Shirburnian Society). It was also a best seller.[5] (The Society's website gives a different version: Alec and his father resigned and were not reinstated until 1933, while Evelyn went to a different school). Robert Graves wrote in a letter sent from Liverpool to his friend Siegfried Sassoon, dated 9 September 1917, “That “Loom of Youth” book is amazingly good: I might have written it myself – no that sounds wrong but you understand: what a reckless man to write and publish it ! He is old Gosse’s nephew or something and Gosse was very shy about it till he heard that it was in its fifth edition when he changed his tune.”[6] In 1932, the book was again the subject of controversy when Wyndham Lewis's Doom of Youth seemed to suggest that Waugh's interest in schoolboys was because he was a homosexual. This was settled out of court.[7] In the mid-1960s, Alec donated the original manuscript, press clippings and correspondence with the publisher to the Society.[8]

Waugh served in the British army in France during the First World War, being commissioned in the Dorset Regiment in May 1917,[9] and seeing action at Passchendaele. Captured by the Germans near Arras in March 1918, he spent the rest of the war in prisoner-of-war camps in Karlsruhe and in the Mainz Citadel. Waugh married his first wife, Barbara Annis Jacobs (1900–1996), in 1919.[10]

He later had a career as a successful author, although never as successful or innovative as that of his younger brother. He lived much of his life overseas, in exotic places such as Tangier – a lifestyle made possible by his second marriage in 1932 to a rich Australian, Joan Chirnside, only child and heiress of Andrew Spence Chirnside (1856-1934) of Edrington, Berwick, Victoria and Vite Vite, Derrinallum, Victoria,[11] nephew of Thomas Chirnside. His work, possibly in consequence, tended to be reminiscent of W. Somerset Maugham, although without achieving Maugham's huge popular success. Nevertheless, his 1955 novel Island in the Sun was a best-seller. It was filmed in 1957 as Island in the Sun, securing from Hollywood the greatest amount ever paid for the use of a novel at that time.[12] His 1973 novel A Fatal Gift was also a success. Despite these successes, his waggish nephew Auberon once joked that Waugh "wrote many books, each worse than the last."[13][14]

Waugh served in the British army during the Second World War as an Intelligence Officer. He was posted to France (serving under Gerald Wellesley, his Hampshire neighbour), Syria, the Lebanon, Egypt, and Iraq, ending the War with the rank of Major.[15]

He was a wine connoisseur, and published In Praise of Wine & Certain Noble Spirits (1959), a light-hearted and discursive guide to the major wine types, and Wines and Spirits, a 1968 book in the Time-Life series Foods of the World.[16]

In 1969, Waugh married the author Virginia Sorensen, and they resided together in Morocco, then moved to the United States as his health failed. He died in Florida at the age of 83.

Works

edit- The Loom of Youth (1917), published by Grant Richards, London (Bloomsbury Reader, 2012, ISBN 978-1-4482-0052-8 )

- Resentment Poems (1918), published by Grant Richards, London

- The Prisoners of Mainz (1919), published by Chapman & Hall, London

- Pleasure (1921), published by Grant Richards, London with dust wrapper designed by John Austen (illustrator)

- Public School Life: Boys, Parents, Masters (1922), published by W Collins Sons & Co., London

- The Lonely Unicorn (1922), published by Grant Richards, London and published in the USA by MacMillan Co, New York (1922) as "Roland Whately"

- Myself When Young: Confessions (1923), published by Grant Richards, London

- Card Castle (1924), published by Grant Richards, London

- Kept: A Story of Post-war London (1925), published by Grant Richards, London

- Love In These Days (1926)

- On Doing What One Likes (1926), published by The Cayme Press, Kensington, London

- Nor Many Waters (1928), published by Chapman & Hall, London

- The Last Chukka: Stories of East and West (1928), published by Chapman & Hall, London

- Three Score and Ten (1929), published by Chapman & Hall, London

- Portrait of a Celibate (1929)

- "...'Sir,' She Said" (1930), published by Chapman & Hall, London

- The Coloured Countries (1930), published by Chapman & Hall, London

- Hot Countries (1930), published by Farrar and Rinehart, New York, with woodcuts by Lynd Ward

- Most Women (1931), published by Farrar & Rinehart, New York, with woodcuts by Lynd Ward

- So Lovers Dream (1931), published by Cassell and Company, London with dust wrapper designed by Eric Fraser (illustrator) and published in the USA by Farrar & Rinehart, New York (1932) as "That American Woman"

- Leap Before You Look (1932), published by Ernest Benn Limited

- No Quarter (1932), published by Cassell and Company, London with dust wrapper designed by Eric Fraser (illustrator) and published in the USA by Farrar & Rinehart, New York (1932) as "Tropic Seed"

- Thirteen Such Years (1932), published by Cassell & Company, London

- Wheels Within Wheels (1933), published by Cassell & Company, London

- The Balliols (1934), published by Cassell & Company, London with dust wrapper designed by Eric Fraser (illustrator)

- Jill Somerset (1936), published by Cassell & Company, London

- Eight Short Stories (1937), published by Cassell & Company, London

- Going Their Own Ways (1938), published by Cassell & Company, London

- No Truce With Time (1941), published by Farrar & Rinehart, New York

- His Second War (1944), published by Cassell & Company, London

- The Sunlit Caribbean (1948), published by Evans Brothers, London

- These Would I Choose (1948), published by Sampson Low, London

- Unclouded Summer (1948), published by Cassell & Company, London

- The Sugar Islands: A Caribbean Travelogue (1949), published by Farrar, Straus And Company, New York

- The Lipton Story (1950), published by Doubleday & Co, New York and in the UK by Cassell & Company, London (1951)

- Where the Clocks Chime Twice (1951), published by Farrar, Straus & Young, New York and in the UK published by Cassell & Company, London (1952)

- Guy Renton (1952), published by Farrar, Straus & Young, New York and in the UK published by Cassell & Company, London (1953)

- Island in the Sun (1955), published by Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, New York and in the UK published by Cassell & Company, London (1956)

- Merchants of Wine: Being a Centenary Account of the Fortunes of the House of Gilbey (1957)

- The Sugar Islands: A Collection of Pieces Written About the West Indies Between 1928 and 1953 (1958), published by Cassell & Company, London

- In Praise of Wine (1959), published by Cassell & Company, London

- Fuel for the Flame (1959), published by the Book Club, London and in the USA published by Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, New York (1960) and in the UK published by Cassell & Company, London (1960)

- My Place in the Bazaar (1961), published by Cassell & Company, London

- The Early Years of Alec Waugh (1962), published by Cassell & Company, London

- A Family of Islands: A History of the West Indies 1492 to 1898 (1964), published by Weidenfeld And Nicholson, London

- Mule on the Minaret (1965), published by Cassell & Company, London

- My Brother Evelyn and Other Portraits (1967), published by Cassell & Company, London

- Foods of the World: Wines and Spirits (1968), published by Time Life, USA

- A Spy in the Family (1970), published by W. H. Allen, London

- Bangkok: The Story of a City (1970), published by W. H. Allen, London

- A Fatal Gift (1973), published by W. H. Allen, London

- A Year to Remember: A Reminiscence of 1931 (1975), published by W. H. Allen, London

- Married to a Spy (1976), published by W. H. Allen, London

- The Best Wine Last: An Autobiography Through the Years 1932–1969 (1978), published by W. H. Allen, London

Bibliography

edit- Fathers and Sons: The Autobiography of a Family; by Alexander Waugh, 2004.

- New York Life: Of Friends and Others; by Brendan Gill, 1994.

References

edit- ^ Stannard, Martin (1986). Evelyn Waugh The Early Years 1903-1939 (1st ed.). J M Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 15. ISBN 9780460046329.

- ^ Stannard, Martin (1986). Evelyn Waugh The Early Years 1903-1939 (1st ed.). J M Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 12. ISBN 9780460046329.

- ^ Hastings, Selina (1994). Evelyn Waugh A Biography (1st ed.). Sinclair-Stevenson Ltd. pp. Page 3. ISBN 9781856192231.

- ^ Alec Waugh, The Loom of Youth (London: Methuen 1984) p. 135 et seq.

- ^ Alec Waugh, The Loom of Youth (London: Methuen 1984) p. 12.

- ^ https://portal.sds.ox.ac.uk/articles/online_resource/65884_Letter_To_Siegfried_Sassoon/25554936

- ^ Bradford Morrow and Bernard Lafourcade, A Bibliography of the Writings of Wyndham Lewis (Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press, 1978), p.65

- ^ The Old Shirburnian Society - Alec Waugh and The Loom of Youth

- ^ London Gazette 7 August 1917. Page 6

- ^ "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ Argus (Melbourne) (18 April 1934). "https://oa.anu.edu.au". Obituaries Australia.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Nicholas Shakespeare, "Which of today's novelists will stand the test of time?", The Daily Telegraph, 9 January 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016

- ^ Waugh, Auberon (1991). Will this do? the first fifty years of Auberon Waugh: an autobiography. London: Century. ISBN 978-0-7126-3733-6.

- ^ Joan Acocella, "Waugh Stories: Life in a Literary Dynasty", The New Yorker, 2 July 2007.

- ^ Waugh, Alec (1978). The Best Wine Last: An autobiography through the years 1932-1969 (1st ed.). W H Allen. pp. 137–212. ISBN 9780491023740.

- ^ Ayto, John. (2006) Movers And Shakers: A Chronology of Words That Shaped Our Age. Page 61. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861452-7.