Overview

Necrotizing soft-tissue infections (NSTIs) are potentially life-threatening medical emergencies that encompass a devastating and rapidly spreading destruction of soft tissue with associated systemic toxicity. [1] While the term necrotizing fasciitis was first described in 1952, fasciitis is only one subset of NSTIs. [2]

NSTI is a rare diagnosis with a wide spectrum of presentations in the emergency department (ED). The most significant challenge associated with NSTI is establishing an early diagnosis. [3] Skin may not be involved initially, which may delay treatment in a patient who may appear healthy. [4, 5] During the first stages, NSTIs may be confused with cellulitis or other superficial skin infections. [3]

The infectious process can be located anywhere in the body, with a characteristic rapid progression of the infection site and hyperacute systemic deterioration of the patient.

The spread of the infection can lead to limb amputation, and the risk for mortality has been estimated to be 15-35%, though this may reach 100% if source control is not obtained. [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 3] The rapid clinical course is assumed to be related to microbial virulence, and many studies show that most cases are polymicrobial as opposed to monomicrobial with an organism such as group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus or Streptococcus pyogenes. [6] One of the most important factors in patient survival is time to diagnosis and debridement. [11, 12, 3]

The lack of universal terminology used to define NSTIs and similar infections makes nomenclature confusing. Definitive treatment remains early and aggressive surgical intervention, and delay often results in increased risks of morbidity and mortality. [9, 13]

Pathophysiology

The etiology of necrotizing soft-tissue infections (NSTIs) is not always obvious. Pathogens can gain entry with a small site of inoculation, blunt trauma, cutaneous infections, post-surgical complications, hematogenous spread, burns, childbirth, or idiopathic causes. [14]

Individuals with multiple comorbidities are at an increased risk for NSTI. Risk factors include recent trauma (one of the most common risks [15] ), intravenous drug use (IVDU), diabetes (strongly associated with type I NSTI), steroid use, immunocompromise, peripheral vascular disease, obesity, liver disease, chronic renal failure, and alcohol use. IVDU is one of the most common risk factors associated with community-acquired NSTI and may account for 5%-88% of cases in the western United States, likely associated with black tar heroin. [16, 17] Nonetheless, healthy people without these risk factors also may be susceptible, [4] especially for type II NSTI. [18, 19] In fact, up to half of patients have no inciting event. [5]

NSTIs can be defined as life-threatening infections of any of the layers within the soft-tissue compartment that are associated with necrotizing changes. NSTIs can range from skin and subcutaneous necrosis to muscle and fascial involvement, but classification is less important than the general principles. [11, 18, 20, 3]

The specific pathophysiology of NSTIs depends on the involved pathogen and mechanism. NSTI is pathophysiologically characterized by effects of bacterial toxins and enzymes (eg, hyaluronidase) that enable horizontal extension through the fascial planes, leading to intravascular thromboses and ischemic necrosis with disturbance of the host’s humoral and cellular immune response. [21] Inflammation and necrosis spread along the fascia and muscle, with vascular occlusion an integral part of the pathophysiology. The infection usually is polymicrobial. Typical pathogens include group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus, Staphylococcus aureus (including community-associated methicillin-resistant S aureus [CA-MRSA]), Enterococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, Bacteroides, and clostridia.

Clinical manifestations of NSTI can include rapidly evolving signs of systemic compromise and devastating infection with signs of tissue destruction, skin manifestations of blistering, and hemorrhage with crepitus.

Necrotizing fasciitis can be a misleading term used to describe an aggressive infection of subcutaneous tissue and the superficial fascia. Histologically, the necrosis of the fascia can manifest with or without polymorphonuclear infiltrates or bacteria. Surgical findings include presence of foul-smelling “dishwater” pus and gray, friable necrotic fascia that does not resist blunt dissection. [22] The infection primarily does not affect musculature, but the prolongations of the deep fascia reach the surroundings of the skeletal muscle; progression to intermuscular fascia involvement and myonecrosis are signs of late-stage disease and indicate a poor prognosis. [23, 24]

Fournier gangrene is a fulminant necrotizing fasciitis of the genitourinary tract. It is a well-defined urological emergency that rapidly progresses to the entire perineum and abdominal wall. A handful of studies have described several scoring systems for Fournier gangrene, such as Fournier’s Gangrene Severity Index (FGSI), surgical Apgar score (sAPGAR), and Uludag Fournier's Gangrene Severity Index (UFGSI), to predict the likelihood of mortality. [25]

Myonecrosis is a rare, potentially lethal condition that refers to necrotic infection of the muscle. The terms gas gangrene and clostridial myonecrosis have been used to refer to necrosis of the muscle tissue caused by toxin-producing clostridia. Other bacteria also are capable of producing gas. Nonclostridial organisms have been isolated in 60-85% cases of NSTIs with subcutaneous gas, and the term gas gangrene has been used to describe any gas-forming soft-tissue infection. [26]

Spontaneous gangrenous myositis (also known as spontaneous streptococcal gangrenous myositis, group A streptococcal necrosis, or streptococcal myonecrosis) is very rare. It is characterized by rapidly progressing necrotizing S pyogenes infection of skeletal muscle, usually preceded by influenza-like symptoms.

Epidemiology and Microbiology

Epidemiology

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) monitors specific infections in the United States, including necrotizing fasciitis, with a special system called Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs), based on causal organism. Each year in the United States, approximately 650-850 cases of necrotizing fasciitis caused by group A Streptococcus are reported, although this figure is probably low owing to underreporting. [27]

The incidence of NSTI is approximately 500-1500 cases per year, with a recent increase thought to be related to increased microbial virulence and antibiotic resistance. [6] Worldwide, the incidence of NSTIs ranges from 1.69-15.5 cases per 100,000 persons per year. [28, 29, 30, 31]

Microbiology

NSTI can be classified based on microbial etiology. Type I infections are the most common and are polymicrobial. [6, 14] Type II NSTI is monomicrobial in etiology and is associated with streptococci, staphylococci, and clostridia. Staphylococcal NSTI is increasing in prevalence owing to more cases of MRSA infection and association with IVDU, particularly the use of black tar heroin.

Classification of NSTIs based on microbiology is as follows [32, 3] :

-

Type I: Polymicrobial etiology (most common) with aerobic, anaerobic, and facultative anaerobic species; this form typically is seen in individuals with comorbidities and/or elderly patients.

-

Type II: Monomicrobial etiology ( Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Clostridium); Staphylococcal NSTI is increasing in prevalence owing to more cases of MRSA infection and association with recent surgery, trauma, or IVDU, particularly the use of black tar heroin. Group A streptococcal infection has been associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use. [33, 34]

-

Type III: Vibrio vulnificus (associated with seawater exposure, in individuals with underlying cirrhosis, or raw oyster ingestion) or Aeromonas hydrophila (associated with wounds exposed to freshwater).

-

Type IV: Fungal sources such as Candida or Zygomycetes in the setting of penetrating injury may result in NSTI.

Differential Diagnoses

Limb ischemia

Presentation and Diagnosis

NSTI describes necrosis that involves subcutaneous fat, fascia, or muscle. It can present with a wide variety of clinical findings, and objective confirmation becomes difficult during the early stages of the infection. [35, 3] Misdiagnosis of the condition ranges from 41-96%, [15] most commonly as abscess or cellulitis. No set of history/examination findings, laboratory results, or imaging findings can definitively rule out NSTI. [10] Surgical exploration may be required for definitive diagnosis, with surgical visualization of necrotic and avascular tissue appearing as dull and gray considered the criterion standard. [7] The “finger test” can be completed in uncertain cases, in which an incision is made into the deep fascia under local anesthesia, followed by probing with the index finger. [4, 36] “Dishwater pus,” no bleeding, and the absence of resistance to blunt dissection confirm the diagnosis.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rapidly progressive, highly destructive bacterial infection that can initiate as an apparently benign skin infection with an area of painful erythema and edema, similar to simple cellulitis. Common initial findings include swelling, pain, and erythema, present in 70-80% of patients. [37, 11, 32, 3] Findings in more advanced necrotizing fasciitis include dusky skin and yellowish to red-black fluid-filled bullae that rapidly progresses to a demarcated area of necrosis resembling a third-degree burn, evolving to frank cutaneous gangrene with penetration along deep fascial planes and myonecrosis. Other manifestations include thrombophlebitis in the lower extremities, bacteremia, septic shock, and hypotension with rapid death. [38, 39]

Myonecrosis, which is characteristically associated with clostridial infection, may result in a bronze color, followed by hemorrhagic bullae, dermal gangrene, and, finally, crepitus. Nonclostridial infections are usually associated with erythema, pain, and swelling but are frequently initially identical to simple cellulitis. An apparent superficial cellulitis that fails to respond to standard antibiotic therapy and that progresses rapidly, resulting in systemic toxicity, should raise suspicion for necrotizing soft-tissue infection (NSTI).

A seroma with partial or complete dehiscence of a recent operative incision are potentially suggestive of necrotizing infection. The patient should be returned to the operating room for tissue biopsy and thorough examination of all layers of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia, muscle, and peritoneum.

Chronic edema resulting in venous stasis or peripheral vascular disease, as well as preexisting diabetic foot wounds, are associated with NSTIs. NSTIs occur more commonly in patients with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, chronic alcoholism, chronic renal disease, HIV disease, liver disease, and underlying malignancy. [40, 41]

NSTI of the head and neck can result in Ludwig angina or Lemierre syndrome. [42, 43] In rare cases, necrotizing infections can occur in the retroperitoneum and have cutaneous manifestations on the abdominal wall as a complication of intra-abdominal infectious processes, perforated viscous, or severe pancreatitis complicated by abscess. [44, 45]

NSTIs can be difficult to diagnose early in the disease course, as initial signs and symptoms can be typical of cellulitis. As mentioned previously, the classic examination finding of pain out of proportion to examination or pain extending beyond the border of infection are both concerning for NSTI. [3] Hemorrhagic bullae, ecchymosis, tense edema, and crepitus are later findings. Bullae, skin necrosis, and crepitus are found in 20-25% of cases. [15] Subcutaneous emphysema, while considered classic, is found in only 13-31% of cases. [4] However, if these findings are present, NSTI should be assumed until proven otherwise.

It is common for patients with NSTI to present with signs of systemic toxicity, including hypotension and fever, [15, 10, 46, 47, 3] due to a systemic inflammatory response caused by cytokine release. Gastrointestinal symptoms may be present in streptococcal NSTI. [32] Septic shock is associated with a poor prognosis. However, some patients with underlying chronic illness may be relatively immunosuppressed and demonstrate a less-dramatic presentation.

Some patients present with “la belle indifference” and, despite a severely infected extremity, seem inappropriately unbothered, which may be a result of local ischemia causing the skin to become insensate.

One European study identified the presence of initial visible skin necrosis as an independent predictor of mortality. [48]

The most important discriminative information to be established in patients with soft-tissue infection is the presence of a necrotizing component. This will confirm NSTI and, by definition, identifies patients who require surgical debridement. The first and most important tool for early diagnosis of NSTI is a high index of suspicion. Unfortunately, true risk factors for NSTI have not been identified. [7]

See the images below.

Left upper extremity shows necrotizing fasciitis in an individual who used illicit drugs. Cultures grew Streptococcus milleri and anaerobes (Prevotella species). Patient would grease, or lick, the needle before injection.

Left upper extremity shows necrotizing fasciitis in an individual who used illicit drugs. Cultures grew Streptococcus milleri and anaerobes (Prevotella species). Patient would grease, or lick, the needle before injection.

Necrotizing fasciitis at a possible site of insulin injection in the left upper part of the thigh in a 50-year-old obese woman with diabetes.

Necrotizing fasciitis at a possible site of insulin injection in the left upper part of the thigh in a 50-year-old obese woman with diabetes.

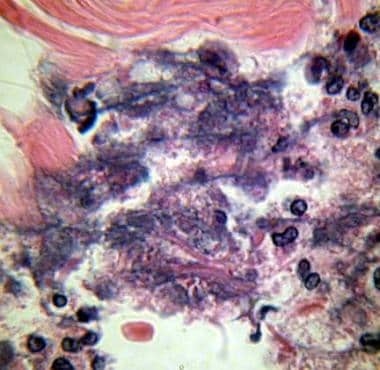

Photomicrograph of Fournier gangrene (necrotizing fasciitis), oil immersion at 1000× magnification. Note the acute inflammatory cells in the necrotic tissue. Bacteria are located in the haziness of their cytoplasm. Courtesy of Billie Fife, MD, and Thomas A. Santora, MD.

Photomicrograph of Fournier gangrene (necrotizing fasciitis), oil immersion at 1000× magnification. Note the acute inflammatory cells in the necrotic tissue. Bacteria are located in the haziness of their cytoplasm. Courtesy of Billie Fife, MD, and Thomas A. Santora, MD.

When evaluating a patient for possible NSTI, the border of erythema should always be marked upon initial evaluation to assess for rapid advancement, which suggests NSTI.

Imaging Studies

Radiographic studies can demonstrate subcutaneous emphysema, but this is a late finding and should not be used to rule out NSTI. However, if present, it is associated with severe disease. [49] Sensitivity of gas formation discovered on plain radiography ranges from 25-50%, although it is highly specific. [7, 10, 36] Plain radiography is also unable to reveal involvement of deep fascial layers.

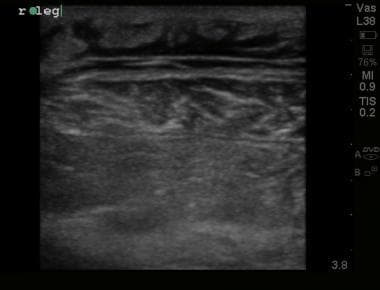

Emergency ultrasonography can be used to aid in the diagnosis. [50, 51] Ultrasonographic findings include fascial and subcutaneous thickening, fluid accumulation in the deep fascia, and hyperechoic foci with reverberation artifacts from subcutaneous gas. [50, 52] These findings have been incorporated into the STAFF (subcutaneous thickening, air, and fascial fluid) examination. [53] See the image below.

Ultrasound image demonstrating thickened, irregular fascial plane with edema within underlying muscle representing myonecrosis in patient with confirmed necrotizing fasciitis.

Ultrasound image demonstrating thickened, irregular fascial plane with edema within underlying muscle representing myonecrosis in patient with confirmed necrotizing fasciitis.

MRI with gadolinium contrast is superior to all other imaging modalities because of its remarkable soft-tissue capabilities, with sensitivity approaching 100%. [54, 55] Intermuscular fluid collection and variable fascial thickening are useful findings; however, T2 hyperintensity in the deep muscular fascia is an important feature for diagnosis. [56, 57] Unfortunately, MRI is associated with increased time to diagnosis and the need for clinical stability. In unstable patients, it delays surgical intervention. [6] MRI also may overestimate myofascial involvement. [58]

CT scan is superior to plain radiography. [10] CT may demonstrate fascial thickening and inflammation, free fluid (particularly along the deep fascia), fat stranding and inflammation surrounding affected areas, one or multiple abscesses, and/or subcutaneous emphysema. [59, 60, 61, 62, 57] Gas alone on CT is not sensitive but is highly specific. [57] When using a combination of findings for NSTI, overall CT sensitivity approaches 90%, with high specificity as well. [10] However, as the senstivity is not 100%, CT should not be used alone to exclude NSTI.

Laboratory Assessment

The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score has been used to gauge the likelihood of NSTI. [26] The LRINEC score includes 6 variables associated with NSTI and is used to calculate a score correlating to the risk for NSTI (see tables 1 and 2 below). Patients with an LRINEC score of 6 or higher have been considered at highest risk for the presence of a necrotizing infection. While the score may suggest necrotizing fasciitis, it should not be used to exclude the diagnosis, as the score was retrospectively developed and demonstrates poor sensitivity in patients in the emergency department (ED). [63] In fact, studies suggest that it may miss over 20% of patients with necrotizing fasciitis in an ED setting. [10, 63, 64, 65] A case of necrotizing fasciitis with a LRINEC score of 0 has been published. [66] Patients still need a thorough evaluation to rule out the disease. Not included in the LRINEC score is a serum lactate level, which, if elevated, should also increase concern for NSTI. Patients with concern for NSTI can rapidly deteriorate and should be reevaluated frequently. Studies have suggested the LRINEC score has limited sensitivity, particularly in patients with early infection, and early surgical consultation is recommended if the disease is suspected. [10, 3]

Other important laboratory markers associated with poor prognosis include elevated leukocyte count, creatine kinase level, liver function, renal function, and lactate dehydrogenase level. Decreased levels of sodium, potassium, calcium, hematocrit, pH, total protein, and albumin also portend a poor prognosis. [67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72] Leukocytosis of 15,400 cells/µL with a sodium level of less than 135 mmol/L may differentiate NSTI from other infections, with a negative predictive value of 99%. [73] A rapid antigen detection test (RADT) for group A streptococcus may be obtained of the affected tissue, but it does not have 100% sensitivity. [74]

The NSTI assessment score (NAS) is a relatively newer scoring system that incorporates clinical and laboratory findings (mean arterial pressure, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin, serum creatinine, and glucose), but further study is needed. [75]

Importantly, use of a clinical score or laboratory findings alone should not be used to exclude NSTI.

Table 1. LRINEC Score Parameters (Open Table in a new window)

Laboratory Parameter |

LRINEC Points |

C-reactive protein (mg/L) |

|

< 150 |

0 |

≥ 150 |

4 |

Total white blood cell count (µL) |

|

< 15 |

0 |

15-25 |

1 |

>25 |

2 |

Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

|

>13.6 |

0 |

11-13.5 |

1 |

< 10.9 |

2 |

Sodium (mmol/L) |

|

≥ 135 |

0 |

< 135 |

2 |

Creatinine (mg/dL) |

|

≤ 1.6 |

0 |

>1.6 |

2 |

Glucose (mg/dL) |

|

≤ 180 |

0 |

>180 |

1 |

Table 2. LRINEC Score and Risk of NSTI (Open Table in a new window)

Risk Category |

LRINEC Score, Points |

Probability of NSTI, % |

Low |

< 5 |

< 50 |

Intermediate |

6-7 |

50-70 |

High |

>8 |

>75 |

Emergency Department Management

Early recognition of necrotizing soft-tissue infections (NSTIs) is critical and requires a coordinated multidisciplinary approach. Patients with suspected necrotizing fasciitis must be promptly and aggressively treated to reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality. [76, 3]

Obtain intravenous access in the unaffected extremity and begin fluid resuscitation with normal saline or lactated Ringer solution. In patients who do not improve with crystalloid resuscitation, administration of vasopressors such as norepinephrine is recommended.

Administer adequate intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics, as the etiology can be polymicrobial.

Consider supplemental oxygen and intubation in patients with hypoxia or altered mental status.

Appropriate analgesic administration is recommended, as patients may have significant analgesic requirements.

Electrolyte replacement is indicated as needed.

Immediate surgical consultation is indicated when NSTI is suspected. A surgeon should be promptly consulted for definitive management.

Tetanus status should be assessed and updated, if indicated.

Antibiotic Selection

Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic therapy should be initiated upon suspicion for possible NSTI. Antibiotic selection should cover gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. The current Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) guidelines recommend broad-spectrum coverage (vancomycin or linezolid plus [1] piperacillin-tazobactam or a carbapenem or [2] ceftriaxone and metronidazole). [76] One of the antibiotics should be a toxin-suppressing and cytokine-modulating medication, such as clindamycin or linezolid. [77, 78] If vancomycin is administered, clindamycin also should be provided. However, if linezolid is available, it may be used in combination with the other medication class (eg, beta lactam-beta lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem) in place of vancomycin and clindamycin, as linezolid provides coverage for MRSA and inhibits toxin production. If the patient has severe hypersensitivity to beta lactam-beta lactamase inhibitors or carbapenems, an aminoglycoside or fluoroquinolone PLUS metronidazole can be substituted. [3]

Organism-specific management is as follows: [76]

-

Mixed infections: (1) Piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g IV every 6-8 h, (2) imipenem-cilastatin 1 g IV every 6-8 h IV, (3) meropenem 1 g IV every 8 h, (4) ertapenem 1 g IV daily, or (5) cefotaxime 2 g IV every 6 h with metronidazole 500 mg IV every 6 h PLUS clindamycin 600-900 mg IV every 8 h PLUS vancomycin 30 mg/kg/d in 2 divided doses OR linezolid 600 mg IV every 12 h

-

Streptococcus and Clostridium species: Penicillin 2-4 million units IV every 4-6 h plus clindamycin 600-900 mg IV every 8 h

-

S aureus: Nafcillin 1-2 g IV every 4 h, oxacillin 1-2 g IV every 4 h, cefazolin 1 g IV every 8 h, vancomycin (resistant strains) 30 mg/kg/d IV in 2 divided doses, or clindamycin 600-900 mg IV every 8 h

-

V vulnificus: Doxycycline 100 mg IV every 12 h plus ceftriaxone 1 g IV qid, or cefotaxime 2 g IV qid

-

Aeromonas hydrophila: Doxycycline 100 mg IV every 12 h plus ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV every 12 h, or ceftriaxone 1-2 g IV every 24 h

Debridement and Definitive Surgical Management

Aggressive surgical debridement of all necrotic tissue is the definitive treatment of NSTIs. Studies suggest improved survival in patients undergoing surgery within 24 hours of admission, compared to those in whom surgery is delayed, [11, 79] and survival further increases with operative intervention within 6 hours. [80] Although pus may be nearly absent, wounds can discharge copious amount of tissue fluid. Antibiotic treatment alone without surgical intervention leads to progressive sepsis. Debridement is best accomplished by early and extensive incision of skin and subcutaneous tissue wide into healthy tissue, followed by excision of all necrotic fascia and nonviable skin and subcutaneous tissue. Repeat tissue inspection and debridement often are required. [50]

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) for treatment of NSTIs is controversial, as it has not been proven as a benefit for the patient and can delay resuscitation and surgical debridement. A review of 57 studies found that HBO did not improve outcomes in necrotizing fasciitis. [81] However, more recent studies found improved survival with HBO in the management of necrotizing fasciitis and gas gangrene. [82, 83, 84] HBO involves the use of oxygen at 2-3 times atmospheric pressure with proposed benefits of bactericidal effects, improved polymorphonuclear lymphocyte function, and enhanced wound healing. HBO inhibits anaerobic bacterial growth and clostridium toxin release. There are few controlled clinical studies, with conflicting results. HBO should be considered as a treatment adjunct [85, 86, 87] and does not replace surgical debridement. [41, 88]

Intravenous Immunoglobulin Therapy

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy is an experimental treatment for necrotizing fasciitis and is postulated to bind exotoxin produced by streptococcal and staphylococcal species, potentially delaying the onset of the systemic inflammatory response and sepsis. The use of IVIG has not been definitively established, but it can be considered on a case-by-case basis in hemodynamically unstable, critically ill patients. [89, 90, 91, 92] However, controlled trials are lacking. [93]

Consultations and Transfer

Obtain early surgical consultation for aggressive debridement in cases of suspected necrotizing soft-tissue infection (NSTI) without delay for results of laboratory or radiology studies. [3] Consider surgical subspecialty consultation for necrotizing fasciitis involving specific anatomic areas such as urology in cases of Fournier gangrene or otolaryngology for Ludwig angina. Consultation with an infectious diseases specialist may help guide initial empiric antibiotic therapy. If the current facility is not capable of handling the aggressive care, monitoring, and serial surgical debridement that these patients require, arrangements for transfer should be made. However, patients should not be considered for transfer until they remain hemodynamically stable. Patients with NSTI should be admitted to an intensive care unit due to the need for consistent reevaluation and close monitoring and the risk for hemodynamic compromise.

-

Left upper extremity shows necrotizing fasciitis in an individual who used illicit drugs. Cultures grew Streptococcus milleri and anaerobes (Prevotella species). Patient would grease, or lick, the needle before injection.

-

Necrotizing fasciitis at a possible site of insulin injection in the left upper part of the thigh in a 50-year-old obese woman with diabetes.

-

Photomicrograph of Fournier gangrene (necrotizing fasciitis), oil immersion at 1000× magnification. Note the acute inflammatory cells in the necrotic tissue. Bacteria are located in the haziness of their cytoplasm. Courtesy of Billie Fife, MD, and Thomas A. Santora, MD.

-

Ultrasound image demonstrating thickened, irregular fascial plane with edema within underlying muscle representing myonecrosis in patient with confirmed necrotizing fasciitis.