Tarek El-Ariss

Dartmouth College, Middle Eastern Studies, Faculty Member

Research Interests:

Originally delivered as the 2021 CARGC Distinguished Lecture in Global Communication, CARGC Paper 17 historicizes and situates theory in a global context, approaching it as an intellectual tradition that has produced powerful critiques of... more

Originally delivered as the 2021 CARGC Distinguished Lecture in Global Communication, CARGC Paper 17 historicizes and situates theory in a global context, approaching it as an intellectual tradition that has produced powerful critiques of normativity and decentered text, image, and genealogy. In this paper, Professor Tarek El-Ariss revisits his intellectual trajectory and scrutinizes his engagement with critical theory. Reflecting on his personal journey as a scholar, writer, and critic in this article, he delineates five stages of critical practice in his encounters with theory, comparative literature, and Middle Eastern studies. These five stages are: a critique of representation, occupy the canon, impasse and breakdown, cross-disciplinary sublime, and new writing genres. By offering a wide-ranging and insightful overview of the five-stage theoretical practice in this paper, Professor El-Ariss addresses some of the questions and ethical imperatives that we need to raise as an intellectual community today in order to develop new critical practices, writing genres, and forms of communication that operate at both local and global levels.

Research Interests:

What does scandal designate? Is it a narrative of moral outrage, a titillating spectacle of shame, or a violation that simultaneously unsettles and consolidates norms and traditions? Scandal as a phenomenon, event, and analytical category... more

What does scandal designate? Is it a narrative of moral outrage, a titillating spectacle of shame, or a violation that simultaneously unsettles and consolidates norms and traditions? Scandal as a phenomenon, event, and analytical category has been the focus of de bates and representations in works by Kant, Heidegger, Rousseau, Sade, and Mme de Sévigné, as well as in The Arabian Nights. These engagements with scandal in philosophy, literature, and media constitute a genealogy if not a tradition that emphasizes the relations between scandal and the body, gender, story-telling, visuality, marginality, and pow er. From the body of Aphrodite that frames scandal in the Greek mythological context to the body of Egyptian activist and nude blogger Alyaa Elmahdi, adulterous affairs and fantasies of debauchery particularly have been used as instruments to critique the rich and powerful but also to oppress women and sexual minorities. What becomes of scandal in the age of the Internet, apps, and social media? The article examines whether the digital is bringing about the demise of scandal as an affective scene that generates outrage and condemnation but also as a model of telling and representing tied to antiquated re portage genres, gossip scenes, and fictional models. Genealogy The word "scandal" comes from the Greek word skandalon, which means moral stumble and trap. 1 One of the most famous scandals in antiquity is the one generated by the adul terous relation between the god of war, Ares (Mars), and the goddess of beauty, Aphrodite (Venus) or Cypris, as she comes from the eastern part of the Greek world (the island of Cyprus). Homer tells us that when Ares stayed in Aphrodite's bed into dawn, Helios, the sun god, making his journey from east to west, saw the lovers in bed. Helios, best known as the gossiper among the gods as he sees everything, told Aphrodite's husband Hephaistos, thereby setting the scene of scandal on Mount Olympus. 2 Following Helios's "seeing" and "gossiping," Hephaistos, the blacksmith who works in the forge all night, laid a "trap" for the lovers: an invisible chain net that would fall and immobilize them when set. A revealer, a whistleblower, and artificer, Helios sets the stage for the scene of scandal.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

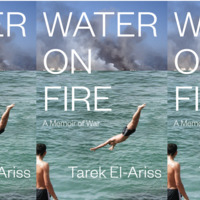

On growing up in Beirut during the War

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Can the exile ever return? And if so, how? This question has consumed literature from the times of Gilgamesh. Focusing on works by the Jāhilī poet al-Shanfarā (d. 70/525) and the contemporary Lebanese author Hudā Barakāt, this essay reads... more

Can the exile ever return? And if so, how? This question has consumed literature from the times of Gilgamesh. Focusing on works by the Jāhilī poet al-Shanfarā (d. 70/525) and the contemporary Lebanese author Hudā Barakāt, this essay reads the metamorphosis of the exile and the outcast as a critique of tribal identification. I argue that while the moment of exilic departure is confounded and erased, the return (al-ʿawdah) operates as a form of revenge (raiding, haunting, possessing) that emerges from experiences of tawaḥḥush (becoming wild, beastly) and tagharrub (estrangement, alienation). This vengeful return harnesses beastliness and alienation as both destructive and productive forces that dismantle communal rituals of inclusion and exclusion, death and burial, while opening up the human/beast relation to multiple social and political configurations. Drawing on classical and contemporary theoretical frameworks , I examine the function of cruelty in the exile's transformation and return, reading it as a survival mechanism and aesthetic device.