Introduction

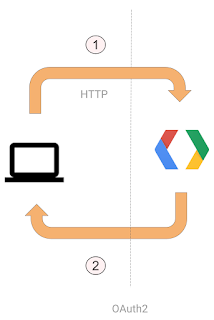

Earlier today at Google I/O, the Hangouts Chat team (including yours truly) delivered a featured talk on the bot framework for Hangouts Chat (talk video here [~40 mins]). If you missed it several months ago, Google launched the new Hangouts Chat application for G Suite customers (but not consumer Gmail users at this time). This next-generation collaboration platform has several key features not available in "classic Hangouts," including the ability to create chat rooms, search, and the ability to attach files from Google Drive. However for developers, the biggest new feature is a bot framework and API allowing developers to create bots that interact with users inside "spaces," i.e., chat rooms or direct messages (DMs).Before getting started with bots, let's review typical API usage where your app must be authorized for data access, i.e., OAuth2. Once permission is granted, your app calls the API, the API services the request and responds back with the desired results, as illustrated here:

Bot architecture is quite different. With bots, recognize that requests come from users in chat rooms or DMs. Users direct messages towards a bot, then Hangouts Chat relays those requests to the bot. The bot performs all the necessary processing (possibly calling other APIs and services), collates the response, and returns it to Chat, which in turn, displays the results to users. Here's the summarized bot workflow:

A key takeaway from this discussion is that normally in your apps, you call APIs. For bots, Hangouts Chat calls you. For this reason, the service is extremely flexible for developers: you can create bots using pretty much any language (not just Python), using your stack of choice, and hosted on any public or private cloud. The only requirement is that as long as Hangouts Chat can HTTP POST to your bot, you're good to go.

Furthermore, if you think there's something missing in the diagram because you don't see OAuth2 nor API calls, you'd also be correct. Look for both in a future post where I focus on asynchronous responses from Hangouts Chat bots.

Event types & bot processing

So what does the payload look like when your bot receives a call from Hangouts Chat? The first thing your bot needs to do is to determine the type of event received. It can then process the request based on that event type, and finally, return an appropriate JSON payload back to Hangouts Chat to render within the space. There are currently four event types in Hangouts Chat:-

ADDED_TO_SPACE -

REMOVED_FROM_SPACE -

MESSAGE -

CARD_CLICKED

The 3rd message type is likely the most common scenario, where a bot has been added to a room, and now a human user is sending it a request. The other common type would be the last one. Rather than a message, this event occurs when users click on a UI card element. The bot's job here is to invoke the "callback" associated with the card element clicked. A number of things can happen here: the bot can return a text message (or nothing at all), a UI card can be updated, or a new card can be returned.

All of what we described above is realized in the pseudocode below (whether you choose to implement in Python or any other supported language) and helpful in preparing you to review the official documentation:

def process_event(req, rsp):

event = json.loads(req['body']) # event received

if event['type'] == 'REMOVED_FROM_SPACE':

# no response as bot removed from room

return

elif event['type'] == 'ADDED_TO_SPACE':

# bot added to room; send welcome message

msg = {'text': 'Thanks for adding me to this room!'}

elif event['type'] == 'MESSAGE':

# message received during normal operations

msg = respond_to_message(event['message']['text'])

elif event['type'] == 'CARD_CLICKED':

# result from user-click on card UI

action = event['action']

msg = respond_to_click(

action['actionMethodName'], action['parameters'])

else:

return

rsp.send(json.dumps(msg))

Regardless of implementation language, you still need to make the necessary tweaks to run on the hosting platform you choose. Our example uses Google App Engine (GAE) for hosting; below you'll see the obvious similarities between our actual bot app and this pseudocode.

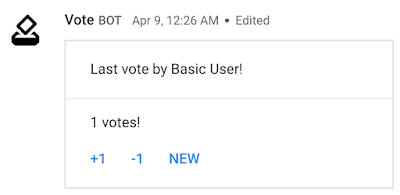

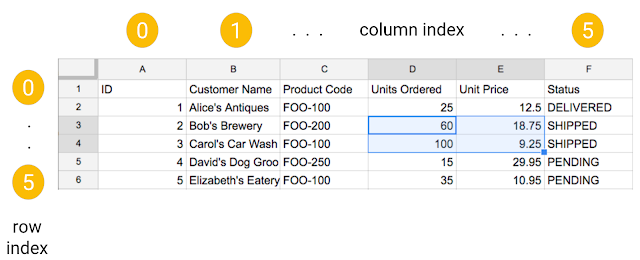

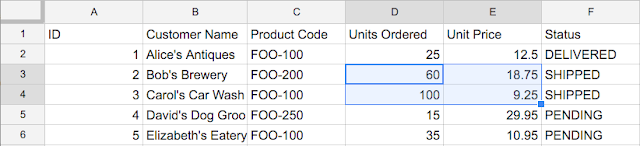

Polling chat room users for votes

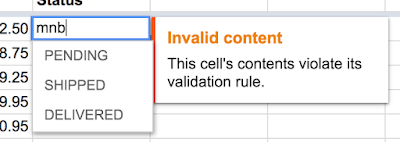

For a basic voting bot, we need a vote counter, buttons for users to upvote or downvote, and perhaps some reset or "new vote" button. To implement it, we need to unpack the inbound JSON object, determine the event type, then process each event type with actions like this:-

ADDED_TO_SPACE— ignore.. we don't do anything unless asked by users -

REMOVED_FROM_SPACE— no action (bot removed) -

MESSAGE— start new vote -

CARD_CLICKED— process "upvote", "downvote", or "newvote" request

webapp2 micro framework:

class VoteBot(webapp2.RequestHandler):

def post(self):

event = json.loads(self.request.body)

user = event['user']['displayName']

if event['type'] == 'CARD_CLICKED':

method = event['action']['actionMethodName']

if method == 'newvote':

body = create_message(user)

else:

delta = 1 if method == 'upvote' else -1

vote_count = int(event['action']['parameters'][0]['value']) + delta

body = create_message(user, vote_count, True)

elif event['type'] == 'MESSAGE':

body = create_message(user)

else: # no response for ADDED_TO_SPACE or REMOVED_FROM_SPACE

return

self.response.headers['Content-Type'] = 'application/json'

self.response.out.write(json.dumps(body))

If you've never written an app using webapp2, don't fret, as this example is easily portable to Flask or other web framework. Why didn't I write it with Flask to begin with? Couple of reasons: 1) the webapp2 framework comes native with App Engine... no need to go download/install it, and 2) because it's native, I don't need to deploy any other files other than bot.py and its app.yaml config file whereas with Flask, you're uploading another ~1300 files in addition this pair. (More on this towards the end of this post.)Compare this real app to the pseudocode... similar, right? Our bot is a bit more complex in that it renders UI cards, so the

create_message() function will need to do more than just return a plain text response. Instead, it must generate and return the JSON markup rendering the card in the Hangouts Chat UI:def create_message(voter, vote_count=0, should_update=False):

PARAMETERS = [{'key': 'count', 'value': str(vote_count)}]

return {

'actionResponse': {

'type': 'UPDATE_MESSAGE' if should_update else 'NEW_MESSAGE'

},

'cards': [{

'header': {'title': 'Last vote by %s!' % voter},

'sections': [{

'widgets': [{

'textParagraph': {'text': '%d votes!' % vote_count}

}, {

'buttons': [{

'textButton': {

'text': '+1',

'onClick': {

'action': {

'actionMethodName': 'upvote',

'parameters': PARAMETERS,

}

}

}

}, {

'textButton': {

'text': '-1',

'onClick': {

'action': {

'actionMethodName': 'downvote',

'parameters': PARAMETERS,

}

}

}

}, {

'textButton': {

'text': 'NEW',

'onClick': {

'action': {

'actionMethodName': 'newvote',

}

}

}

}]

}]

}]

}]

}

Finishing touches

The last thing App Engine needs is anapp.yaml configuration file:

runtime: python27 api_version: 1 threadsafe: true handlers: - url: /.* script: bot.appIf you've deployed apps to GAE before, you know you need to create a project in the Google Cloud Developers Console. You also need to have a project for bots, however you can use the same project for both your use of the Hangouts Chat bot framework (link only works for G Suite customers) as well as hosting your App Engine-based bot.

Once you've deployed your bot to GAE, go to the Hangouts Chat API configuration tab, and add the HTTP endpoint for your App Engine-based bot to the Conenctions Settings section:

As you can see, there are several options here for where Hangouts Chat can post messages destined for bots: standard HTTPS bots like our App Engine example, Google Apps Script (a customized JavaScript-in-the-cloud platform with built-in G Suite integration [intro video]), or Google Cloud Pub/Sub. Pub/Sub is the message queue proxy for when your bot is hosted on-premise behind a firewall, requiring you to register a pull subscription to retrieve bot messages from Hangouts Chat.

Once you've published your bot, add the bot to a room or @mention it in a DM. Send it a message, and it returns an interactive vote card like what you see below. Cast some votes or create a new vote to test drive your new bot.

Conclusion

Congrats for creating your first Python bot! Below is the entirebot.py file for your convenience. (At this time, Python App Engine standard only supports Python 2, so if you want to run Python 3 instead, use the Python App Engine flexible environment.) Also don't forget the app.yaml configuration file above.import json

import webapp2

def create_message(voter, vote_count=0, should_update=False):

PARAMETERS = [{'key': 'count', 'value': str(vote_count)}]

return {

'actionResponse': {

'type': 'UPDATE_MESSAGE' if should_update else 'NEW_MESSAGE'

},

'cards': [{

'header': {'title': 'Last vote by %s!' % voter},

'sections': [{

'widgets': [{

'textParagraph': {'text': '%d votes!' % vote_count}

}, {

'buttons': [{

'textButton': {

'text': '+1',

'onClick': {

'action': {

'actionMethodName': 'upvote',

'parameters': PARAMETERS,

}

}

}

}, {

'textButton': {

'text': '-1',

'onClick': {

'action': {

'actionMethodName': 'downvote',

'parameters': PARAMETERS,

}

}

}

}, {

'textButton': {

'text': 'NEW',

'onClick': {

'action': {

'actionMethodName': 'newvote',

}

}

}

}]

}]

}]

}]

}

class VoteBot(webapp2.RequestHandler):

def post(self):

event = json.loads(self.request.body)

user = event['user']['displayName']

if event['type'] == 'CARD_CLICKED':

method = event['action']['actionMethodName']

if method == 'newvote':

body = create_message(user)

else:

delta = 1 if method == 'upvote' else -1

vote_count = int(event['action']['parameters'][0]['value']) + delta

body = create_message(user, vote_count, True)

elif event['type'] == 'MESSAGE':

body = create_message(user)

else: # no response for ADDED_TO_SPACE or REMOVED_FROM_SPACE

return

self.response.headers['Content-Type'] = 'application/json'

self.response.out.write(json.dumps(body))

app = webapp2.WSGIApplication([

('/', VoteBot),

], debug=True)

Yep, the entire bot is made up of just these 2 files. While porting to Flask is fairly straightforward and Flask apps are supported by App Engine, Flask itself doesn't come with App Engine (quickstart here), so you'll need to upload all of Flask (in addition to those 2 files) to host a Flask version of your bot on GAE.Both files are also available from this app's GitHub repo which you can fork. I'm happy to entertain PRs for any bugs you find or ways we can simplify this code even more. Below are some additional resources for learning about Hangouts Chat bots and GAE:

- Hangouts Chat bots concepts page

- Creating new Hangouts Chat bots guide

- Hangouts Chat guide to interactive cards

- Other Hangouts Chat sample bots

- Official Hangouts Chat developer documentation—everything you need to know and more!

- Python App Engine (standard) documentation

- Google App Engine product information

Epilogue: code challenge

While usable, this vote bot can be significantly improved. Once you get the basic bot working, I recommend the following enhancements as exercises for the reader:- Support vote topics: users starting new votes must state topic in bot message; use as card header

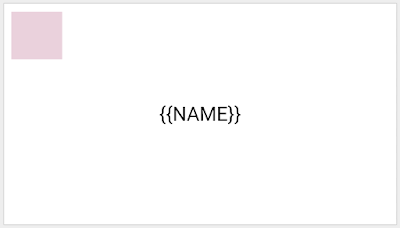

- Add images (like the Node.js version of our vote bot in the docs hosted on Google Cloud Functions)

- Track users who have voted (you decide on implementation)

- Don't let the vote count to go below zero

- Allow downvotes only from users who have at least one upvote

- Port your working bot from

webapp2to Flask