Stampede (Joe Crump)

- 28. 28

- 29. 29

- 30. 30

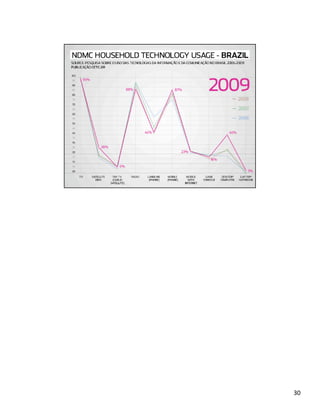

- 31. So here is the summary chart: 1) Aher minimal year‐over‐year changes, the purchase of desktop computers shot up 15% in the last year, largely because local Brazilian manufacturers are now producing extremely inexpensive laptops well within the budgets of the NDMC. 2) The number of landline phones has dropped 17.2%, driven primarily by the inverse increase by 10.6% in the number of mobile phones. 3) And interesJngly, despite the penetraJon of mobile phones, the use of those phones to access the web has increased only 2.4%. This is a direct side‐effect of the price of mobile data plans, which are prohibiJvely expensive for the NDMC. 31

- 33. 33

- 34. 34

- 35. 35

- 38. 38

- 39. 39

- 40. 40

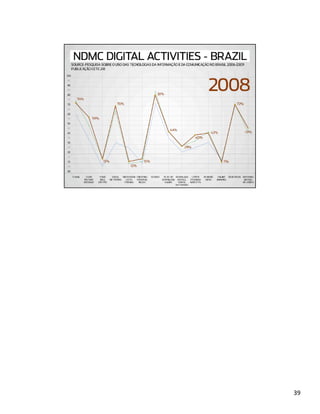

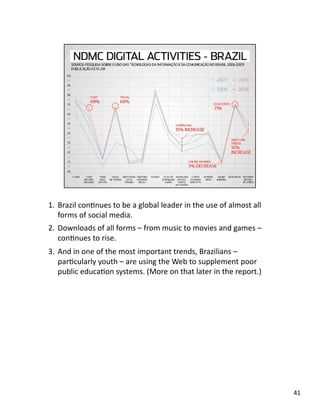

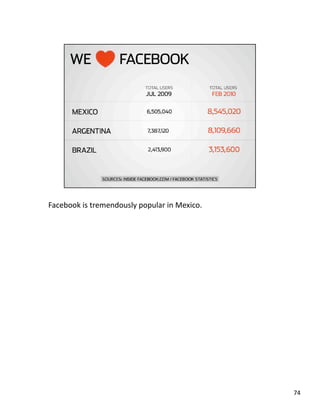

- 41. 1. Brazil conJnues to be a global leader in the use of almost all forms of social media. 2. Downloads of all forms – from music to movies and games – conJnues to rise. 3. And in one of the most important trends, Brazilians – parJcularly youth – are using the Web to supplement poor public educaJon systems. (More on that later in the report.) 41

- 85. 85