Capital Account Convertibility: By, Mithilesh Borgaonkar

Uploaded by

Loveleen SinghCapital Account Convertibility: By, Mithilesh Borgaonkar

Uploaded by

Loveleen SinghCapital Account Convertibility

By, Mithilesh Borgaonkar Shilpa Grover, Sanchit Gupta, Amit Kumar, Avinash Ojha

IMI 12/2/2011

Abstract The report is an analysis of the article written by Y.V Reddy, Former Governor of RBI and highlights the Capital Account Convertibility issue which is currently under high debate in India. This report is an attempt to highlight the different aspect of Capital Account Convertibility and their implication on an economy. It also uses economic models like IS-LM and Mundell Flemming model, to explain the advantages and disadvantages of the CAC. The various aspects of Fiscal and Monetary policy are discussed in the report which helps in stabilising the economy and the implication of full capital mobility. The report also highlights the dilemma of Greece and tries to address the problem by unravelling the issue using economic models.

Group 8 Section B Presented By, Shilpa Grover

Mithilesh Borgaonkar

Amit Kumar

Avinash Ojha

Sanchit Gupta

Balance of payments (BOP) Balance of payments (BOP) accounts are an accounting record of all monetary transactions between a country and the rest of the world. These transactions include payments for the country's exports and imports of goods, services, financial capital, and financial transfers. The BOP accounts summarize international transactions for a specific period, usually a year, and are prepared in a single currency, typically the domestic currency for the country concerned. Sources of funds for a nation, such as exports or the receipts of loans and investments, are recorded as positive or surplus items. Uses of funds, such as for imports or to invest in foreign countries, are recorded as negative or deficit items. When all components of the BOP accounts are included they must sum to zero with no overall surplus or deficit. For example, if a country is importing more than it exports, its trade balance will be in deficit, but the shortfall will have to be counter-balanced in other ways such as by funds earned from its foreign investments, by running down central bank reserves or by receiving loans from other countries. While the overall BOP accounts will always balance when all types of payments are included, imbalances are possible on individual elements of the BOP, such as the current account, the capital account excluding the central bank's reserve account, or the sum of the two. Imbalances in the latter sum can result in surplus countries accumulating wealth, while deficit nations become increasingly indebted. The term "balance of payments" often refers to this sum: a country's balance of payments is said to be in surplus (equivalently, the balance of payments is positive) by a certain amount if sources of funds (such as export goods sold and bonds sold) exceed uses of funds (such as paying for imported goods and paying for foreign bonds purchased) by that amount. There is said to be a balance of payments deficit (the balance of payments is said to be negative) if the former are less than the latter.

Capital Account Transaction v/s Current Account Transaction?

current account =balance of trade +net factor income +net transfer payments balance of trade=exports minus imports of goods and services Net factor income= e.g interest and dividends Net transfer payments =e.g foreign aid. A surplus in the capital account means money is flowing into the country, but unlike a surplus in the current account, the inbound flows will effectively be borrowings or sales of assets rather than earnings. A deficit in the capital account means money is flowing out the country, but it also suggests the nation is increasing its claims on foreign assets.

Capital Account Transaction At high level: Capital account=change in foreign ownership of domestic assets -change in domestic ownership of foreign assets Breaking this down: Capital account=FDI +Portfolio Investment +Other Investment +Reserve Account

Foreign direct investment (FDI) , refers to long term capital investment such as the purchase or construction of machinery, buildings or even whole manufacturing plants. If foreigners are investing in a country, that is an inbound flow and counts as a surplus item on the capital account. If a nation's citizens are investing in foreign countries, that's an outbound flow that will count as a deficit. After the initial investment, any yearly profits not re-invested will flow in the opposite direction, but will be recorded in the current account rather than as capital. Portfolio investment refers to the purchase of shares and bonds. It's sometimes grouped together with "other" as short term investment. As with FDI, the income derived from these assets is recorded in the current account; the capital account entry will just be for any international buying or selling of the portfolio assets. Other investment includes capital flows into bank accounts or provided as loans. Large short term flows between accounts in different nations are commonly seen when the market is able to take advantage of fluctuations in interest rates and / or the exchange rate between currencies. Sometimes this category can include the reserve account. Reserve account. The reserve account is operated by a nation's central bank, and can be a source of large capital flows to counteract those originating from the market. Inbound capital flows, especially when combined with a current account surplus, can cause a rise in value (appreciation) of a nation's currency, while outbound flows can cause a fall in value (depreciation). If a government (or, if authorized to operate independently in this area, the central bank itself) doesn't consider the market-driven change to its currency value to be in the nation's best interests, it can intervene.

Capital Account Convertability Freedom to residents to convert local financial assets into foreign assets, and/or to take on foreign liabilities and invest proceeds in India or abroad. Freedom to non residents to create rupee assets or liabilities and alter them For example:It might legalise to keep money in a Swiss Bank

Problems with CAC: Several economists are of the view that the full Capital Account Convertibility (and allowing the exchange rate to be market determined) has serious consequences on the wellbeing of the country, and this may even lead to extreme sufferings of the common masses. Some of the reasons are highlighted below. During the good years of the economy, it might experience huge inflows of foreign capital, but during the bad times there will be an enormous outflow of capital under herd behaviour (refers to a phenomenon where investors acts as herds, i.e. if one moves out, others follow immediately). For example, the South East Asian countries received US$ 94 billion in 1996 and another US$ 70 billion in the first half of 1997. However, under the threat of the crisis, US$ 102 billion flowed out from the region in the second half of 1997, thereby accentuating the crisis. This has serious impact on the economy as a whole, and can even lead to an economic crisis as in South-East Asia. There arises the possibility of misallocation of capital inflows. Such capital inflows may fund low-quality domestic investments, like investments in the stock markets or real estates, and desist from investing in building up industries and factories, which leads to more capacity creation and utilisation, and increased level of employment. This also reduces the potential of the country to increase exports and thus creates external imbalances. An open capital account can lead to the export of domestic savings (the rich can convert their savings into dollars or pounds in foreign banks or even assets in foreign countries), which for capital scarce developing countries would curb domestic investment. Moreover, under the threat of a crisis, the domestic savings too might leave the country along with the foreign investments, thereby rendering the government helpless to counter the threat. Entry of foreign banks can create an unequal playing field, whereby foreign banks cherry-pick the most creditworthy borrowers and depositors. This aggravates the problem of the farmers and the small-scale industrialists, who are not considered to be credit-worthy by these banks. In order to remain competitive, the domestic banks too refuse to lend to these sectors, or demand to raise interest rates to more competitive levels from the subsidised rates usually followed. International finance capital today is highly volatile, i.e. it shifts from country to country in search of higher speculative returns. In this process, it has led to economic crisis in numerous developing countries. Such finance capital is referred to as hot money in todays context. Full capital account convertibility exposes an economy to extreme volatility on account of hot money flows. Monetary Policy

Monetary policy is the process by which the monetary authority of a country controls the supply of money, often targeting a rate of interest for the purpose of promoting economic growth and stability. The official goals usually include relatively stable prices and low unemployment. Monetary theory provides insight into how to craft optimal monetary policy. It is referred to as either being expansionary or contractionary, where an expansionary policy increases the total supply of money in the economy more rapidly than usual, and contractionary policy expands the money supply more slowly than usual or even shrinks it. Expansionary policy is traditionally used to try to combat unemployment in a recession by lowering interest rates in the hope that easy credit will entice businesses into expanding. Contractionary policy is intended to slow inflation in hopes of avoiding the resulting distortions and deterioration of asset values.

Monetary policy differs from fiscal policy, which refers to taxation, government spending, and associated borrowing Fiscal Policy: The three possible stances of fiscal policy are neutral, expansionary and contractionary. The simplest definitions of these stances are as follows:

A neutral stance of fiscal policy implies a balanced economy. This results in a large tax revenue. Government spending is fully funded by tax revenue and overall the budget outcome has a neutral effect on the level of economic activity. An expansionary stance of fiscal policy involves government spending exceeding tax revenue. A contractionary fiscal policy occurs when government spending is lower than tax revenue.

However, these definitions can be misleading because, even with no changes in spending or tax laws at all, cyclical fluctuations of the economy cause cyclical fluctuations of tax revenues and of some types of government spending, altering the deficit situation; these are not considered to be policy changes. Therefore, for purposes of the above definitions, "government spending" and "tax revenue" are normally replaced by "cyclically adjusted government spending" and "cyclically adjusted tax revenue". Thus, for example, a government budget that is balanced over the course of the business cycle is considered to represent a neutral fiscal policy stance. CAPITAL ACCOUNT CONVERTIBILITY IN INDIA What is capital account convertibility? There is no formal definition of capital account convertibility (CAC). The Tarapore committee set up by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in 1997 to go into the issue of CAC defined it as the freedom to convert local financial assets into foreign financial assets and vice versa at market determined rates of exchange. In simple language what this means is that CAC allows anyone to freely move from local currency into foreign currency and back. The pre-requisites for Capital Account Convertibility in India: The Tarapore Committee appointed by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was meant for recommending methods of converting the Indian Rupee completely. The report submitted by this Committee in the year 1997 proposed a three-year time period (1999-2000) for total conversion of Rupee. However, according to the Committee, this was possible only when the following few conditions are satisfied: The average rate of inflation should vary between 3 % to 5 % during the debt servicing time. Decreasing the gross fiscal deficit to the GDP ratio by 3.5 % in 1999-2000.

Why is CAC an issue of debate? CAC is widely regarded as one of the hallmarks of a developed economy. It is also seen as a major comfort factor for overseas investors since they know that anytime they change their mind they will be able to re-convert local currency back into foreign currency and take out their money. In a bid to attract foreign investment, many developing countries went in for CAC in the 80s not realising that free mobility of capital leaves countries open to both sudden and huge inflows as well as outflows, both of which can be potentially destabilising. More important, that unless you have the institutions, particularly financial institutions, capable of dealing with such huge flows countries may just not be able to cope as was demonstrated by the East Asian crisis of the late nineties. Following the East Asian crisis, even the most ardent votaries of CAC in the World Bank and the IMF realised that the dangers of going in for CAC without adequate preparation could be catastrophic. Since then the received wisdom has been to move slowly but cautiously towards CAC with priority being accorded to fiscal consolidation and financial sector reform above all else. In India, the Tarapore committee had laid down a three-year road-map ending 1999-2000 for CAC. It also cautioned that this time-frame could be speeded up or delayed depending on the success achieved in establishing certain pre-conditions primarily fiscal consolidation, strengthening of the financial system and a low rate of inflation. With the exception of the last, the other two preconditions have not yet been achieved.

Advantages and Drawbacks of CAC CAC can be beneficial for a country as the inflow of foreign investment increases and the transactions are much easier and occur at a faster pace. CAC also initiates risk spreading through diversification of portfolios. Moreover, countries gain access to newer technologies which translate into further development and higher growth rates. Even though CAC seems to have many advantages, in reality, it can actually destabilize the economy through massive capital flight from a country. Not only are there dangerous consequences associated with capital outflow, excessive capital inflow can cause currency appreciation and worsening of the Balance of Trade. Furthermore, there are overseas credit risks and fears of speculation. In addition, it is believed that CAC increases short term FIIs more than long term FDIs, thus leading to volatility in the system.

Position of CAC in India today If one were to judge the implications of CAC in India, independent of its general pros and cons, CAC may not be such a good idea in the near future. The instability in the international markets due to the sub prime crisis and fears of a US recession are adversely affecting the entire world, including India. Moreover, rising oil prices which touched $100 a barrel recently are also fueling inflationary pressures in the economies, worldwide.

Not only is there instability in the international arena, but Indias domestic economy is also going through ups and downs. The rising prices and the appreciation of the rupee are adversely affecting Indias exports and the Balance of Trade. Moreover, the fiscal deficit has been highly underestimated by ignoring the deficits of individual states and through issuance of oil bonds to the public sector oil companies, making severe losses due to the heavy subsidies on oil. The government is yet to compensate these companies and these deferred payments have been left out from the deficit. Also, corruption, bureaucracy, red tapism and in general, a poor business environment, are discouraging the inflow of investment. Poor infrastructure and socio-economic backwardness act as deterrents to FDI inflow. Hence, India still needs to work on its fundamentals of providing universal quality education and health services and empowerment of marginalized groups, etc. The growth strategy needs to be more inclusive. There is no point trying to add on to the clump at the top of the pyramid if the base is too weak. The pyramid will soon collapse! Thus, before opening up to financial volatility through the implementation of FCAC, India needs to strengthen its fundamentals and develop a strong base. Hence, India should either wait for a while or implement CAC in a phased, gradual and cautious manner.

IS CURVE

IS curve depicts the demand of the money at a particular income and interest level .For the IS curve, the independent variable is the interest rate and the dependent variable is the level of income (even though the interest rate is plotted vertically). The IS curve is drawn as downward-sloping with the interest rate (i) on the vertical axis and Gross domestic product: Y on the horizontal axis. The initials IS stand for "Investment and Saving equilibrium" IS curve can be said to represent the equilibria where total private investment equals total saving, where the latter equals consumer saving plus government saving (the budget surplus) plus foreign saving (the trade surplus). In equilibrium, all spending is desired or planned; there is no unplanned inventory accumulation. Given expectations about returns on fixed investment, every level of the real interest rate (i) will generate a certain level of planned fixed investment and other interest-sensitive spending: lower interest rates encourage higher fixed investment and the like. In summary, this line represents the causation from falling interest rates to rising planned fixed investment (etc.) to rising national income and output. The IS curve is defined by the equation

where Y represents income, C(Y T(Y)) represents consumer spending as an increasing function of disposable income (income, Y, minus taxes, T(Y), which themselves depend positively on income), I(r) represents investment as a decreasing function of the real interest rate, G represents government spending, and NX(Y) represents net exports (exports minus imports) as a decreasing function of income (decreasing because imports are an increasing function of income)..

It also depicts the equilibrium in commodity market (M/p)d= h Y f r Where r = Interest Rate

Fig IS Curve LM curve For the LM curve, the independent variable is income and the dependent variable is the interest rate. The LM curve shows the combinations of interest rates and levels of real income for which the money market is in equilibrium. It is an upward-sloping curve representing the role of finance and money. The initials LM stand for "Liquidity preference and Money supply equilibrium". Each point on the LM curve reflects a particular equilibrium situation in the money market equilibrium diagram, based on a particular level of income. Two basic elements determine the quantity of cash balances demanded (liquidity preference)and therefore the position and slope of the function:

1) Transactions demand for money: this includes both (a) the willingness to hold cash for everyday transactions and (b) a precautionary measure (money demand in case of emergencies). Transactions demand is positively related to real GDP (represented by Y,and also referred to as income). This is simply explained - as GDP increases, so does spending and therefore transactions. As GDP is considered exogenous to the liquidity preference function, changes in GDP shift the curve. 2) Speculative demand for money: this is the willingness to hold cash instead of securities as an asset for investment purposes.

Mathematically, the LM curve is defined by the equation M / P = L(i,Y), The LM curve shows the combinations of interest rates and levels of real income for which money supply equals money demandthat is, for which the money market is in equilibrium. For a given level of income, the intersection point between the liquidity preference and money supply functions implies a single point on the LM curve: specifically, the point giving the level of the interest rate which equilibrates the money market at the given level of income. Recalling that for the LM curve, the interest rate is plotted against real GDP (whereas the liquidity preference and money supply functions plot interest rates against the quantity of cash balances), an increase in GDP shifts the liquidity preference function rightward and hence raises the interest rate. Thus the LM function is positively sloped.

Fig : Derivation of LM Curve

IS-LM Model

The intersection of the IS and LM curves is the "General Equilibrium" where there is simultaneous equilibrium in both markets Equilibrium in the commodity market occurs only at the IS while LM shows all combinations of Y and r at which money market is in equilibrium. The economy arrives at its general equilibrium at point E0. If the commodity market is out of equilibrium firms will step up or cut down production, pushing the economy back to E0. If the money market is out of equilibrium there will be pressures to adjust r through the sale (purchase) of stocks or bonds pushing the economy back to E0.

Fig : IS LM Curve Effect of Monetary Policy Suppose that desired (natural) level of Y = 8000 (not 7000). There is 1000 gap between actual and natural. To raise GDP the CB must increase money supply (expansionary monetary policy). If natural real GDP is lower than actual real GDP, the CB must decrease MS (contractionary monetary policy). If the CB raises MS to 3000, LM shifts to the RHS, there will be an excess MS of 1000. Individuals transfer some money into savings to buy bonds and stocks. This raises stock and bond prices and reduces r and shifts equilibrium point to right . In case of reducing money supply , the equilibrium shifts to right .

Fig : Shift due to Expansionary Monetary policy Effect Of Fiscal Policy Here we will shift the IS along a fixed LM curve, as shown in figure below. Expansionary fiscal policy shifts the IS curve. An expansionary fiscal policy taking the form of 500 increase in G shifts the IS to the RHS by 2000, the multiplier is still 4. The full fiscal multiplier would shift the economy from E0 to E2. At E2 the money market is not in equilibrium, because (Md/p) would be high (because of high income, while Ms/P is still the same at 2000. This raises r, which in turn reduces planned I and C. At E3 both money and commodity market is in equilibrium but the equilibrium real income will increase by 1000 only. Higher interest rate (7.5% to 10%) accounts for reducing the fiscal multiplier to 2 instead of 4, as planned C and I are cut by 250. thus fully half of the original multiplier is crowded out.This shifts the equilibrium point to right and up and increases GDP.

Fig : Shift due to Expansionary Fiscal Policy

Mundell Fleming Model The MundellFleming model, also known as the IS-LM-BP model, is an economic model first set forth (independently) byRobert Mundell and Marcus Fleming The model is an extension of the IS-LM model .Whereas the traditional IS-LM Model deals with economy under autarky (or a closed economy), the MundellFleming model describes an open economy. The Mundell-Fleming model portrays the short-run relationship between an economy's nominal exchange rate, interest rate, and output (in contrast to the closed-economy IS-LM model, which focuses only on the relationship between the interest rate and output).

BP Curve The BP curve represents the combinations of income and interest rates that yield equilibrium in the Balance of Payments. .By equilibrium, we mean both current account plus capital account (or overall balance) balances We also assume capital is perfectly mobile, i.e a small increase in the interest rate causes an infinite increase in capital inflows and BP curve is horizontal

Fig : BP Curve

Floating & fixed exchange rates In a system of floating exchange rates, e is allowed to fluctuate in response to changing economic conditions. Under fixed exchange rates, the central bank trades domestic for foreign currency at a predetermined price. Floating Exchange Rates Equilibrium Under a freely floating exchange rate and perfect capital mobility, the following three equations derived above determine the equilibrium position. Y = f (i, q; G) Ms/P = LD (i, Y) i = i* f1 <0, f2 >0, f3 >0 LD1 <0, LD2 >0 <IS> <LM> <BOP>

The equilibrium can be pictured as follows:

Fig : Equilibrium Point at Mundell- Fleming Curve

Effect of Fiscal Expansion 1. An increase in G shifts the IS curve upward and to the right. 2. This puts an upward pressure on the domestic interest rate (i > i*). 3. But this immediately invites a massive capital inflow. 4. This appreciates the nominal exchange rate E as well as the real exchange rate q. 5. This worsens the trade balance T. In Y = A + T, as A is increased by fiscal spending, T is reduced by exactly the same amount. Y is unchanged, and only the relative composition of Y is changed. The conclusion is that under a floating exchange rate and perfect capital mobility, fiscal policy is ineffective.

Effect of Monetary Expansion 1. An increase in Ms shifts the LM curve downward and to the right. 2. This puts a downward pressure on the domestic interest rate (i < i*). 3. But this immediately invites a massive capital outflow. 4. This depreciates the nominal exchange rate E as well as the real exchange rate q. 5. This improves the trade balance T. The conclusion is that under a floating exchange rate and perfect capital mobility, monetary policy is very effective.

Fixed exchange rates

Under fixed exchange rates, the central bank stands ready to buy or sell the domestic currency for foreign currency at a predetermined rate. In the Mundell-Fleming model, the central bank shifts the LM* curve as required to keep e at its preannounced rate.

Y = f (i, q; G) Ms/P = LD (i, Y) i = i*

f1 <0, f2 >0, f3 >0 LD1 <0, LD2 >0

<IS> <LM> <BOP>

The only difference from the case of no capital mobility is the BOP condition. Instead of trade balance, we have interest rate equalization. For maintaining Exchange Rate fixed LM cannot shift. The conclusion is that under a fixed exchange rate and perfect capital mobility, monetary policy is ineffective.

Fiscal Policy Expansion If government spending G is increased, the IS curve is pushed up and to the right. But this tends to raise i and generate a massive capital inflow. To prevent an appreciation of the domestic currency, the central bank must buy up dollars, which will increase IR and H. Money supply Ms jumps up and the LM curve shifts out as a consequence. Since both IS and LM shifts to the right, Y is doubly increased. The conclusion is that under a fixed exchange rate and perfect capital mobility, fiscal policy is very effective.

S First assume that capital is perfectly mobile, the price level is fixed, and the exchange rate is fixed. Now trace the effect on output and current account of an expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. Analysis of Expansionary Monetary Policy on Output in Fixed Exchange rate regime

When capital is perfectly mobile, price level is fixed and exchange rate is fixed, the monetary policy becomes completely impotent and the central bank loses control over money supply. A domestic monetary expansion occurs when the central bank (Fed in US or RBI in India) raises the money supply, thus shifting the LM curve to the right. This normally reduces the interest rate and stimulates spending. When the central bank increases the money supply, there immediately are huge capital outflows and losses of International reserves. Thus, the excess money supply is swept away in the capital outflows to other countries which have higher interest rates. Thus the LM curve falls back to original equilibrium position and interest rates fall back to original higher rate regime. Thus the monetary policy has no control over the output of the economy and Central Bank loses control of the money supply when the exchange rate is fixed and capital is perfectly mobile.

IS curve

LM curve

I*

BoP curve

Interest rate Income (Y)

Analysis of Expansionary Monetary Policy on Current Account in a fixed exchange rate regime Current account comprises of net exports (Total exports total imports), net income from abroad, and net unilateral transfer payments. When capital is perfectly mobile, price level is fixed and exchange rate is fixed, the monetary policy has no effect on Current account. With shift in LM curve towards right, the Central Bank increases the money supply in the economy. However the interest rate falls in the country and due to interest rate differentials with other countries, the excess money supply infused by Central Bank goes as Capital outflows to other countries. Thus the total income Y does not change. As a result the total Output remains same and there is no significant increase in Exports or Imports and current account remains unaffected by the change in monetary policy. Analysis of Expansionary Fiscal Policy on Output in a fixed exchange rate regime When monetary policy is weak, fiscal policy is strong and vice versa. A fiscal policy stimulus works by shifting the IS curve to the right. This tends to raise the interest rates relative to the world interest rate and attract inflows of capital, swamping the central bank with reserves. This capital inflow will

lead to a rise in exchange rate. However, under a fixed exchange rate system Central bank must respond by allowing money supply to rise until interest rate returns to its initial level. Thus both LM and IS curves move to the right, as shown below. This also causes the Output Y to increase from Y0 to y1. Y = Y0 IS curve Y = Y1 LM curve

I*

BoP curve

Interest rate Income (Y) Analysis of Expansionary Fiscal Policy on Current Account in Fixed Exchange Rate regime As seen above, expansionary fiscal policy will cause LM and IS curve to shift to right to achieve new equilibrium point at Y= Y1. Thus the income and the total money supply in the economy increases, with constant exchange rate. We know that Autonomous Planned Spending equals induced savings (sY). Y = Ap/s Thus in this case the Autonomous planned spending will rise. Also the demand for real money balances (M/P) equals a fraction h of real income (Y) (M/P)d = hY Also with increase in Income, Real Money balances will increase. This will lead to increased consumer spending on imported goods, whereas the export would remain constant as exchange rate is fixed. This would lead to current account deficit or imbalance in current account of the country. Why do some, especially developing countries impose capital controls? Take a peculiar case of India as a developing country which imposes capital controls to have smooth economic conditions. The sovereign risk crisis which has already erupted in Europe is also threatening other advanced countries with high fiscal deficits and rising debt levels. Emerging economies like India, experiencing a high-speed growth recovery are receiving, once again, large capital inflows from advanced countries that undertook huge liquidity expansion in response to the financial crisis. This has led to a

rise in the prices of both goods and assets in emerging economies, besides exerting upward pressure on their exchange rates. The impact on India is particularly significant. Charts 1 and 2 reveal what is happening in India right in April 2010. Chart 1 shows that from March 2009, FIIs resumed pouring money into Indian stock markets. This has pulled up stock market prices, although they have not touched pre-crisis levels. Chart 2 shows that the rupee has been appreciating against the dollar since March 2009 with the central bank having virtually stopped buying dollars (in net terms) since October 2009. Both these trends spell trouble for the Indian economy. Chart 1: Return of Capital Inflows leading to rising Stock Prices

Chart 2: Rising Rupee as the Central Bank refrains from Intervention

The policy responses recommended by the IMF to mitigate the risks arising from capital inflow surges in emerging economies include:

- A flexible exchange rate allowing appreciation of the currency - Reserve accumulation through currency intervention - Reduction of domestic interest rates - Tightening of fiscal policy to allow for lower interest rates - Strengthening prudential regulation - Liberalisation of capital outflow controls

None of these options are adequate for addressing Indias predicament. The first option means allowing the rupee to appreciate. Two factors weigh against taking this option. First, Indias current account deficit in 2009-10, which is estimated to be about four per cent of GDP, is the highest current account deficit since Independence. Second, the rupee has already appreciated by about 12 per cent against the dollar over the past year (ending April 2010) (the appreciation is higher at 18

per cent in the year ending March 2009, in real effective terms against a 6-currency trade-weighted basket). A further appreciation of the rupee will therefore considerably erode Indias external competitiveness. Buying excess dollars, as recommended by the second option, will mean that, liquidity is injected into the system. Given the high inflation rate in India, this is a flawed response. India has previously resorted to sterilised intervention, but the fiscal costs of such intervention will not be affordable now as India begins its fiscal consolidation. Additionally, sterilisation could keep interest rates high and that may attract more capital flows. The IMF also recommends a reduction in interest rates. India is in the mode of monetary tightening to contain inflation, which is exceptionally high and rising, so interest rates must rise. The fourth option, fiscal tightening, is also unsound. This has already begun but, since monetary tightening will continue for some time it is unlikely to reduce interest rates enough to dissuade capital inflows. The fifth is strengthening prudential regulation. India has a prudent, well-recognised regulatory regime, which helped it weather the global financial crisis. There is little room to further strengthen prudential regulations that could help deal with capital inflow surges and their attendant financial risks. The last option from the IMF report is to relax capital outflow controls. India has been liberalising its capital outflows and has gradually lifted the cap on capital outflows from both resident individuals and corporate entities. While further relaxations are possible, the impact will be limited in the present situation of a fragile global economic recovery. Indias situation is more complex than during earlier episodes of capital inflow surges. Interestingly, the IMF states in its GFSR that if its policy options appear insufficient to meet with the sudden or large increase in capital inflows capital controls may be a useful element in the policy toolkit. This is a break from IMFs long-held position and is based on an in-depth study of the experience of a number of emerging market cases. There are broadly two types of capital controls: administrative and market-based. India already maintains administrative controls on capital account which are either prohibitive in nature or prescribe quantitative limits. During times of excess or scanty capital inflows, India had resorted to tightening or loosening of administrative controls, largely on debt flows. Price or market-based capital controls, on the other hand, discourage capital transactions by increasing their cost. There are two kinds of market-based capital controls that emerging economies take recourse to: unremunerated reserve requirements (URR) and taxes on capital inflows. The former was used by Colombia (2007-08) and Thailand (2006-08) in the pre-crisis period and the latter by Brazil in 2008 and again from October 2009. So far, India has relied largely on administrative controls to tackle a surge in capital inflows. These include controls on both debt and equity inflows. Debt inflows are subject to limits. In the case of equity inflows, while there is no overall limit imposed on the amount, a cap in terms of their proportion to a companys share capital is imposed. However, if FII equity inflows continue to be excessive, the authorities may need to seriously consider a move to price-based controls. Given the serious flaws in other available options, imposing an unremunerated reserve requirement or a tax on FIIs may be the only viable way forward.

It is often said that if currencies come under major attack, letting the exchange rate collapse may be far wiser strategy than using borrowed billions to defend an exchange rate that might prove indefensible. Comment on this policy prescription. First let try to understand what it means by Currency under attack. When an economy starts performing poor and people start losing confidence in the government and Central Bank, the currency starts depreciating. People start selling the currency to buy Dollar or some other safe currency. This devaluation of currency due to loss of faith and other factors can be termed as Attack on currency. The reasons for such devaluation in currency could be because of excess Current account deficit, and many more. Let us try to analyse the effect of both a) letting exchange rate collapse and b) borrowing billions to maintain exchange rate on the economy. Letting Exchange rate collapse When the exchange rate is not fixed, and if currency comes under major attack, by letting exchange rate collapse, the export becomes cheaper leading to increase in exports. At the same time the imports become dearer and thus import decreases. This however causes the trade balance to improve. With improving trade balance and decreasing deficit, the confidence starts to build in and exchange rate starts to rise. Borrowing funds Balance of payments is divided into two main parts 1. First part is the current account which includes next exports, net income from abroad, and net unilateral payments 2. The second part is the capital account, which records the purchase and sale of foreign assets by residents and purchase and sale of domestic assets by foreign residents Any international transaction that creates a payment of money to a domestic resident is a credit. Included are exports of goods and services, investment income on domestic assets held in foreign countries and purchase of domestic assets by foreigners. Debits are opposite to credit and results from the payments of money to foreigners by residents. Debits are created by imports of goods and services, investment income paid on foreign holding of domestic asset, and purchase of foreign assets by residents. The current account deficit could be financed by massive borrowings from foreign governments. The common example is of China and Japan who increased their foreign reserves at very rapid pace to keep their currencies from strengthening against dollar. In effect China and Japan willingly lent hundreds of billions of dollars to US to allow it to import much more than it exports. This strategy may work for US, as US is an exceptional case. However for other Emerging economies, this equation wont be applicable as no country would be willing to invest huge money on a weakened economy. Even if the country manages to borrow funds from other countries, it may be a temporary solution. In long run it will again face such situation and it may have to rethink its strategy. Why Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal have lost the control over important tool of stabilisation monetary policy. Because the European Central Bank (ECB) issues the currency and sets interest rates, the individual Eurozone nations have no control over monetary policy. If labourers migrated between countries,

this would be a manageable problem. With migration, unemployment and other economic imbalances could be worked out. But because of language and cultural differences, there is little migration between Eurozone countries. So huge economic imbalances exist, and there is no effective equilibrating force. Consider first unemployment rates. The rates in the Eurozone powerhouses (Austria, the Netherlands, and Germany) are low. But look at the bottom four. These rates have been high for some time, and such high rates cause serious socio-economic problems. The Spanish rate of 19.4% is particularly grim. It means that one in five Spaniards looking for jobs. The OECD reports that for men in the 15-24 age range, the unemployment rate is 43%! This is not healthy. It invites civil strife. Table1. Unemployment Rates, 2011

Source: IMF WEO Database A Keynesian might say that while Eurozone countries have lost control over their monetary policies, they still can exercise fiscal independence by running government deficits large enough to get back to full employment. Unfortunately, since they do not have their own central banks to buy up the resulting debt, their deficits will be limited to their governments currency reserve holdings and the willingness of others to buy their debt. The four weak sisters currency holdings are limited. And as evidenced by the skyrocketing interest rates they must pay to sell new debt, nobody wants it. Lets now look at two more indicators of problems facing the weak sisters the size of their budgetary and current account deficits. Table 2 provides data on government deficits. The deficits of Austria, Germany and The Netherlands are manageable. There are willing buyers for the new debt generated by their deficits. It is a different story for the weak sisters. Their deficits are much larger, and nobody wants to buy their debt. On top of this, Greece, Ireland, and Portugal have entered into agreements with the ECB/IMF to reduce their deficits. As I have reported earlier, the IMF estimates that a fiscal consolidation of 1% of GDP will result in an increase of .3 percentage points in the unemployment rate. This is crazy and it will be political suicide for the leaders of these countries to continue supporting these agreements.

Table2. Government Deficits, 2011 (as % GDP)

Source: IMF WEO Database It is finally worth examining the current account balances of these countries with the rest of the world. Negative balances means they are buying more than they are selling. The US runs a large current account deficit (-3.1%) But as noted in previous question above, it has been offset by the global demand for US financial assets, specifically US Treasuries and equities. Nobody wants the financial assets of the four weak sisters. And as a consequence, the current account deficits of Greece, Portugal and Spain are not sustainable. This means Euros, will drain out of the countries to make up the deficit. And this is effectively reducing the money supplies of these countries, making their unemployment problems even worse. Table3. Current Account Balances, 2011 (% of GDP)

Source: IMF WEO Database The Root of the Problem What is really wrong here? Labour costs in weak sister countries are too high to clear labour markets. More specifically, the is too strong for these countries. It makes their imports too cheap and exports too expensive to reduce trade deficits and increase domestic employment. This is a classic case of the Dutch Disease, a term coined to explain why other industries do poorly in mineral exporting countries. In the Eurozone, Austria, Germany, and The Netherlands are the mineral export industry: it is because of them that the Euro is so strong. But other Euro members will not fare well because the strong Euro makes them too costly to compete on world markets.

Now in theory, this problem could be resolved if the weak sisters producers (capitalists and labourers) got together and agreed to reduce their costs by 30%. In other words, if they all agreed to take a pay cut of 30%. But this will never happen. What Should Be Done How, realistically, can the weak sisters costs be reduced so that their workers can find jobs again and their trade deficits become manageable via lower imports and higher exports? They should leave the Eurozone and go back to having their own central banks. Why would this help? Because with their own currencies and central banks, their currency exchange rates would fall so their labour would be cheaper and they could compete again on world markets. And instead of having to reduce their government deficits as they are obliged to do under ECB/IMF mandates, they can launch new stimulus packages to get people back to work. These stimulus packages would be financed by their central banks buying up the increased government deficits. Of course, this is just another way to get labour and capital costs down in the weak sister countries. With their new currencies, their imports will be much more expensive and their exports more competitive than under the regime. But this is a workable way to reduce their costs. And yes, their standard of living will fall by 30%. But it has to if they want to put people back to work.

It is not bad for developing countries to run a current account deficit. Explain? A good starting point is to ask what a current account deficit or surplus really means and to draw insights from the many ways that a current account balance is measured. First, it can be expressed as the difference between the value of exports of goods and services and the value of imports of goods and services. A deficit then means that the country is importing more goods and services than it is exporting Second, the current account can be expressed as the difference between national (both public and private) savings and investment. A current account deficit may therefore reflect a low level of national savings relative to investment or a high rate of investmentor both. For capital-poor developing countries, which have more investment opportunities than they can afford to undertake with low levels of domestic savings, a current account deficit may be natural. A deficit potentially spurs faster output growth and economic development.

Convertible currencies are defined as currencies that are readily bought, sold, and converted without the need for permission from a central bank or government entity. Most major currencies are fully convertible; that is, they can be traded freely without restriction and with no permission required. Various types of convertible currency: Fully convertible currency: The U.S. dollar is an example of a fully convertible currency. There are no restrictions or limitations on the amount of dollars that can be traded on the international market, and the U.S. Government does not artificially impose a fixed value or minimum value on the dollar in international trade. For this reason, dollars are one of the major currencies traded in the FOREX market.

Partially convertible currency: The Indian rupee is only partially convertible due to the Indian Central Banks control over international investments flowing in and out of the country. While most domestic trade transactions are handled without any special requirements, there are still significant restrictions on international investing and special approval is often required in order to convert rupees into other currencies. Due to Indias strong financial position in the international community, there is discussion of allowing the Indian rupee to float freely on the market, altering it from a partially convertible currency to a fully convertible one. Nonconvertible currency: Almost all nations allow for some method of currency conversion; Cuba and North Korea are the exceptions. They neither participate in the international FOREX market nor allow conversion of their currencies by individuals or companies. As a result, these currencies are known as blocked currencies; the North Korean won and the Cuban national peso cannot be accurately valued against other currencies and are only used for domestic purposes and debts. Such nonconvertible currencies present a major obstruction to international trade for companies who reside in these countries.

Convertibility of Rupee: Officially, the Indian rupee has a market determined exchange rate. However, the RBI trades actively in the USD/INR currency market to impact effective exchange rates. Thus, the currency regime in place for the Indian rupee with respect to the US dollar is a de facto controlled exchange rate. This is sometimes called a "managed float". Other rates such as the EUR/INR and INR/JPY have volatilities that are typical of floating exchange rates. It should be noted, however, that unlike china, successive administrations (through RBI, the central bank) have not followed a policy of pegging the INR to a specific foreign currency at a particular exchange rate. RBI intervention in currency markets is solely to deliver low volatility in the exchange rates, and not to take a view on the rate or direction of the Indian rupee in relation to other currencies. Also affecting convertibility is a series of customs regulations restricting the import and export of rupees. Legally, foreign nationals are forbidden from importing or exporting rupees, while Indian nationals can import and export only up to 5000 rupees at a time, and the possession of 500 and 1000 rupee notes in Nepal is prohibited. RBI also exercises a system of capital controls in addition to the intervention (through active trading) in the currency markets. On the current account, there are no currency conversion restrictions hindering buying or selling foreign exchange (though trade barriers do exist). On the capital account, foreign institutional investors have convertibility to bring money in and out of the country and buy securities (subject to certain quantitative restrictions). Local firms are able to take capital out of the country in order to expand globally. But local households are restricted in their ability to do global diversification. However, owing to an enormous expansion of the current account and the capital account, India is increasingly moving towards de facto full convertibility. There is some confusion regarding the interchange of the currency with gold, but the system that India follows is that money cannot be exchanged for gold, in any circumstances or any situation. Money cannot be changed into gold by the RBI. This is because it will become difficult to handle it. India follows the same principle as Great Britain and America.

The Implication of making rupee fully convertible on capital account: Capital account and, by extension, full convertibility of the rupee has emerged as an often debated issue in the context of the liberalization process in India. It is worth nothing, at the outset, that India is not alone in its endeavor to make its currency convertibility, nor is it the only country which is facing the daunting task of overcoming several hurdles on its way to full currency convertibility. Indeed, only the developed economics of North America, Western Europe, Japan and Australia have joined the race towards full convertibility. A number of Latin American, Central European and Asian Countries, however, have joined the race towards full convertibility. Aside from India, the list of these countries include Argentina, China, Chile, Columbia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Republic of Korea and Thailand. Importantly, these countries are not at the same stage of currency convertibility. The Korean currency, for example, is much convertible than the Chinese currency. Indeed, it is important to note at the outset that the issue is not a matter of choice between convertibility and non-convertibility. There exists a wide spectrum between these two extremes, and India and the aforementioned countries lie at various points of this spectrum. The important issue, in other words, is to decide the extent to which a currency (say, the rupee)will be convertible at a point of time, and the pace at which it will attain higher levels of convertibility in the future. In order to appreciate the meaning and the implication of currency convertibility, however, one has to first take into consideration two different aspects. A currency, it has to be noted, can be convertible on the current account of balance of payments (BOP), and/or on the capital account of BOP. The currency is deemed fully convertible if it is convertible on both these accounts. A clear understanding of the notion of convertibility, therefore, entails an understanding of the current and capital accounts of BOP. As such, the current account of the BOP comprises trade in goods and services. In other words, the current account balance takes into account exports, imports, and net foreign income from unilateral transfers. The capital account of the BOP, on the other hand, takes into account cross-border flow of funds that are associated with financial or other assets in the trading countries. For example, the direct and portfolio investments made by foreign investors, in India, are captured by the capital account balance of the BOP. The capital account also encompasses foreign investments of Indian companies, foreign aid and bank deposits of Non-resident Indians (NRI).Convertibility as an issue, and subsequently as a goal, was a priority in the agenda of the member countries of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) which was born out of the Bretton Woods Agreement. During the Bretton Woods period,"the term convertibility was used in two different contexts: convertibility into gold and convertibility into other currencies. Only the United States maintained gold convertibility during Bretton woods... Convertibility into other currencies for current account transaction purposes was a main goal of Bretton Woods and was reached, to a large extent, early on in the system; however, the agreements to the IMF allowed more flexibility with regard to the imposition of exchange controls on capital account transactions. The flexibility was partly a result of a prevailing feeling that short-run speculative capital flows could be potentially destabilising and governments should therefore have the freedom to resist them. "Owing to other reasons, developing countries have historically not had convertible currencies. Typically, their currencies have been partially convertible on the current account and the capital of

the BOP, the rationale for the choice being embedded in the macroeconomic realities and the policy perspectives of the countries concerned. In India, the rupee was made convertible on the current account in August 1994. However, the currency as yet has limited convertibility on the capital account, and that indeed is the centre of a countrywide debate. What might be the rationale behind the aforementioned choice: making rupee convertible on the current account while maintaining exchange control for capital account transactions? What, indeed, are the policy implications of free capital mobility that is associated with capital account and have full convertibility? Is India ready for full currency convertibility? Government of India is proceeding step-by-step toward making the rupee fully convertible into foreign currencies. That would make it possible for Indian citizens to buy dollars for capital investment in the New York Stock Exchange. Presently it is possible to buy dollars only for current transactions such as education, business travel and purchase of magazines etc. We have foreign exchange reserves of more than 100 billion dollars and it is increasing everyday. Making the rupee convertible would bring forth demand for these dollars from private investors and take away the pressure from the Reserve Bank to buy the dollars endlessly. But we must take a look at the long-term consequences of this policy. There are three ways in which the dollars brought by foreign investors can be used. One, the rupee can be made convertible so that our citizens can purchase them for outward capital flows from India. The East Asian countries adopted this policy in the nineties. They got into crisis because of this policy. Their citizens too had started sending their savings abroad when foreign investors began to withdraw their money. That had led to a run on their currencies and a steep devaluation of the same. The second solution is that the Reserve Bank continues to buy the dollars and accumulate foreign exchange reserves. This policy has been adopted by China. This policy is also harmful because we would be buying dollars the value of which is certain to fall tomorrow if not today. We would have to incur heavy losses, as the value of our forex reserves will decline along with that of the dollar. The third solution is to allow the price of rupee to increase. That would lead to less inflow of dollars. The problem here is that a strong rupee would adversely affect our exports. The choice then is between three potential problems: (1) due to outflow of our money; (2) due to decline in the value of our forex reserves; and (3) due to problems for our exporters. The three choices can be best examined in the light of East Asian and Chinese experience. The manufacturing activity of products like cars, textiles and toys shifted to the Asian Tigers, as they were then called, in a big way in the nineties. American companies like General Motors were closing down their plants in the US and establishing new ones in Thailand. This was leading to a huge inflow of dollars into East Asia just as there is a huge inflow in India today due to the shifting of services known as 'outsourcing'. Those countries had large forex reserves and were confident of their ability to handle foreign capital flows just as our Government is today. Those countries had made their currencies convertible just as our government is planning to do now. The situation of those countries changed dramatically in 1997. The demand for their textiles, cars and toys in the industrial countries ebbed a little. That led to a reduction in the inflow of dollars into those countries. The foreign investors became bearish and started withdrawing their money. The citizens of those countries followed the footsteps of the foreign investors. Soon the large forex reserves disappeared and their currencies faced a steep devaluation. These Asian tigers have still not recovered from that crisis even after six years. This shows the dangers of making the rupee convertible on the basis of large forex reserves. The experience of Latin American countries like

Argentina also points out to this danger. That country had made its currency convertible. But the perception of foreign investors changed and ultimately it had to suspend convertibility. Our 'huge' forex reserves can similarly disappear in a short time if the rupee is made convertible. China has followed the second policy. She has not made the Yuan renminbi convertible. Chinese citizens do not have the right to buy dollars for making investment in the New York Stock Exchange. Manufacturing activity is increasing in China today in the same manner that it did in East Asian countries in the nineties. This is leading to huge amount of foreign capital inflows into China. The Central Bank of China is purchasing these dollars and investing them in the US to augment her forex reserves. The Bank buys as many dollars as necessary to keep the value of the dollar stable. This is beneficial for the Chinese exporters. The result is that China's exports are rising and imports are comparably less. This is leading to greater income of dollars from exports and less demand for the dollars for imports. The Central Bank is buying these excess dollars and balancing the books. But this formula can be successful only as long as the Central Bank is willing to buy all the excess dollars. Obviously there are limits to this policy because the trade surplus will continue to rise as long as China keeps the value of the renminbi low. The fundamental problem is that the price of goods produced in China is less and that makes her economy competitive. Her exports are large and imports are less. This leads to large receipt of dollars from exports and less demand for them for imports. In a free market the value of the renminbi should increase, the exports should reduce, imports should increase and the books should get balanced. But the Government of China refuses to acknowledge this reality. Instead of allowing the renminbi to rise it is buying the dollars and accumulating huge forex reserves. These reserves are like a cooker the pressure of which is continually rising and can explode any day. Both these policies are not durable. Instead we must allow the rupee to rise against the dollar. This will spontaneously lead to reduced inflows of the dollar. Indeed the problems of our exporters would become worse. But that is the mark of a strong economy. A strong rupee means that we can produce goods at low price. It means that we can obtain high prices for small quantities of our goods. That must be our target. We should not forget that a weak rupee was seen as an indicator of a weak economy. Contrariwise a strong rupee should be seen as a strong Indian economy. We have been misled by the slogan of export-oriented growth. 'Exports' mean that we give away more of our resources. We pack our precious groundwater into wheat and sugar and export it. That is utter foolishness. Instead of looking for larger exports we must develop our domestic markets for higher growth rate. The experience of the East Asian countries shows the dangers of making our Currency convertible on the strength of short-term increase in forex reserves. The ever-increasing forex reserves of China signal the dangers of buying dollars in unlimited quantities. We must chart our own course and let the' rupee appreciate and see fewer exports as an achievement.

100%FDI in retail Big foreign companies buy material from International market at a cheap price in bulk. Hence local producers are put to loss. These big companies, in order to crush competitors sell goods cheap. Later on effective prices of goods are increased. These companies buy in bulk quantities directly from manufacturers. The intermediaries loose business in between. After conquering the markets of Europe and America, these companies have now entered Asian markets . After establishing their footings in Thailand, Indonesia, China, Japan, Philippines, etc in Asia, these companies are now targeting India. In Thailand, there was an adverse impact of FDI on 60,000 small shopkeepers. Big companies share grew by 40%.In China, suppliers and manufacturers are facing problems. Indonesia and Malaysia have specified zones into which these companies can trade. In Japan, Big companies can open their stores outside the city only These Big companies will employ workers at the graduate level and above so people who are below graduate level will not be able to get work. India is largely a self-employed country primarily in agriculture and retail.So,it will create unemployment. It will be beneficial for consumers who will buy goods at cheaper price. It is also good for the Overall Economic growth for India as there will be cash inflow in the country. It will also be beneficial for farmers as these companies would remove the middleman and they will get the agri-commodities at a fair price. More investment will also boost the GDP of the country Technical know-how would also increase as new and modern techniques would be used for selling and producing goods. Big companies would work with improved supply chain and would reduce the wastages by 40% in case of fruits, vegetables. So, considering all the points we conclude that FDI boosts the economy but the fact that small retailers form a large chunk of population. Government can specify regions for the foreign players to operate.

References http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2006/12/basics.htm http://www.morssglobalfinance.com/why-greece-ireland-portugal-and-spain-should-leave-theeurozone/ http://www.grips.ac.jp/teacher/oono/hp/lecture_F/lec08.htm http://www.rferl.org/content/article/1084807.html http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2010/05/21/capital-controls-the-way-forward-for-india/ Chapter 7: International Trade, Exchange Rates, and Macroeconomic Policy by Robert Gordon 12th edition

You might also like

- Chapter .1 Introduction of Balance of PaymentNo ratings yetChapter .1 Introduction of Balance of Payment33 pages

- Components of Balance of Payments I: Ntroduction100% (1)Components of Balance of Payments I: Ntroduction3 pages

- International Economic Linkages and Balance of PaymentsNo ratings yetInternational Economic Linkages and Balance of Payments4 pages

- Kiit School of Management Kiit University BHUBANESWAR - 751024No ratings yetKiit School of Management Kiit University BHUBANESWAR - 75102414 pages

- Linking The Domestic Economy With The Global EconomyNo ratings yetLinking The Domestic Economy With The Global Economy3 pages

- Open Economy (English) ..It Is For Clearing Basics of EcoNo ratings yetOpen Economy (English) ..It Is For Clearing Basics of Eco11 pages

- Alance OF Ayments: Presented By: Vikas Roll No.: 31No ratings yetAlance OF Ayments: Presented By: Vikas Roll No.: 3154 pages

- Morgenthau's Realist Theory (6 Principles)No ratings yetMorgenthau's Realist Theory (6 Principles)7 pages

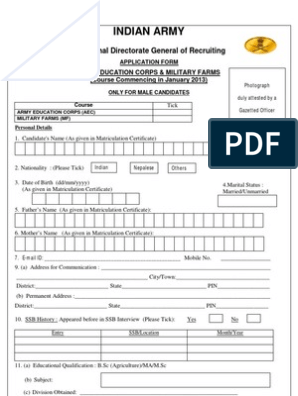

- Common Application Form Army Education AEC & Military Farms (MF) - 22-May-2012 - TGC-116 - AEC & Military Farm - APPLN FORM 12 May 12No ratings yetCommon Application Form Army Education AEC & Military Farms (MF) - 22-May-2012 - TGC-116 - AEC & Military Farm - APPLN FORM 12 May 123 pages

- Will Form - Testator - No Minors, No TrustsNo ratings yetWill Form - Testator - No Minors, No Trusts7 pages

- SRM Uae (Dubai & Abu Dhabi) Global Immersion Programme Study & Industry Tour July - Aug 2024No ratings yetSRM Uae (Dubai & Abu Dhabi) Global Immersion Programme Study & Industry Tour July - Aug 20244 pages

- School of Gospel Missions and Leadership Online Class Time-TableNo ratings yetSchool of Gospel Missions and Leadership Online Class Time-Table2 pages

- PHUNG PHUONG NHI Tahun Kedua ER100314827143553420No ratings yetPHUNG PHUONG NHI Tahun Kedua ER1003148271435534201 page