This is the second of a series of articles. Read the first part.

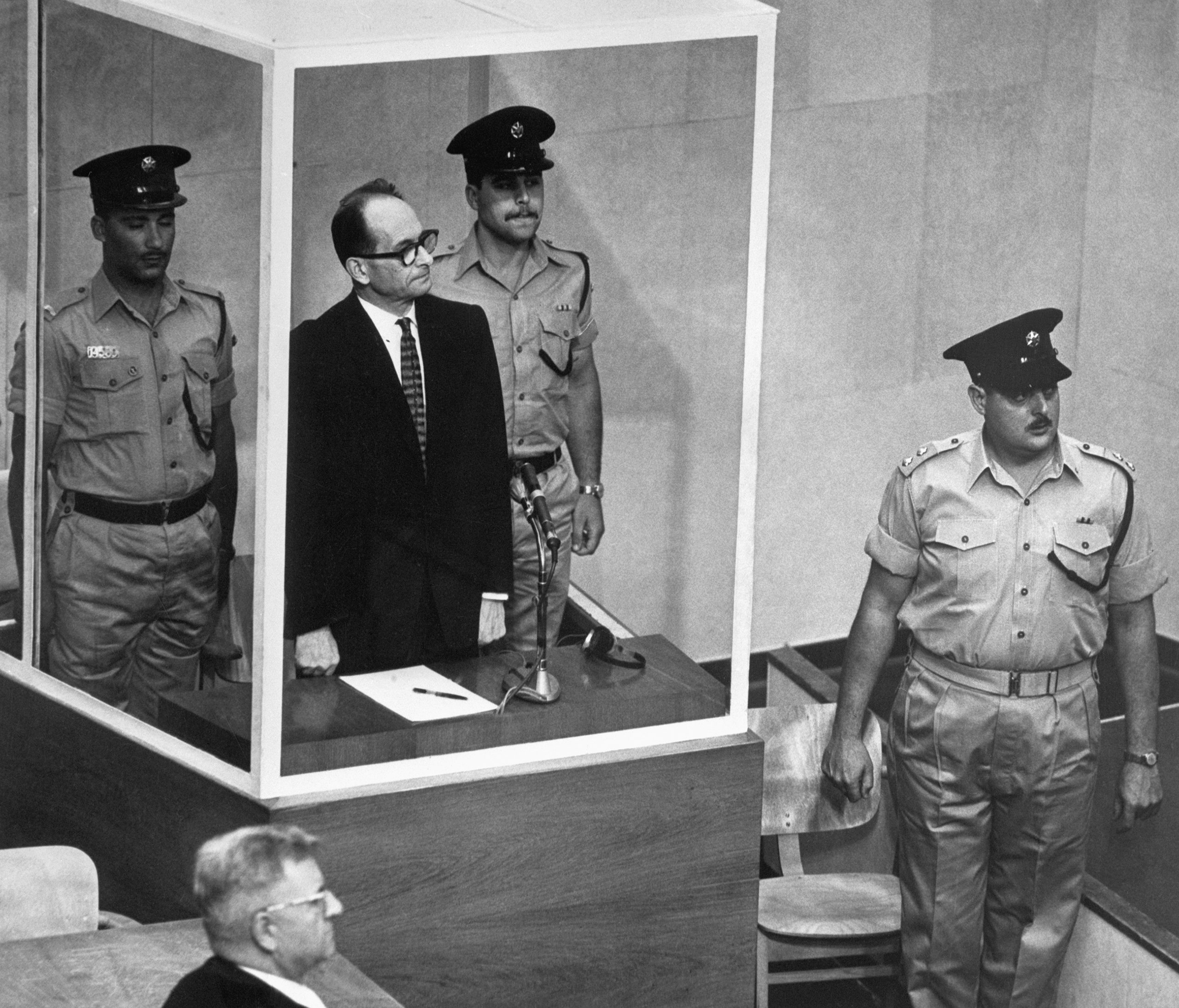

Had the trial of Adolf Eichmann, in Jerusalem, been an ordinary trial, with the normal tug of war between prosecution and defense to bring out the facts on both sides and do justice to them, it would be possible to study the defense and find out whether there was not more to Eichmann’s grotesque account of his activities as head of the Jewish emigration office in Vienna, from the spring of 1938 to the spring of 1939, than meets the eye, and whether his distortions of reality could not really be ascribed to more than personal mendacity. The facts of Eichmann’s later career for which he was eventually hanged had been established “beyond reasonable doubt” long before the trial started, and were generally known to students of the Nazi regime. The additional facts that the prosecution tried to establish were, it is true, partly accepted by the three judges—Moshe Landau, the presiding judge, Benjamin Halevi, and Yitzhak Raveh—in the judgment they handed down, but none of these additional facts would ever have appeared to be “beyond reasonable doubt” if the defense had brought its own evidence to bear upon the proceedings. Hence, no report on the Eichmann case—as distinguished from the Eichmann trial—could be complete without certain facts that Dr. Robert Servatius, counsel for the defense, chose to ignore. This is especially true of Eichmann’s ideology with respect to “the Jewish question.” During cross-examination, he told Judge Landau that during his months in Vienna “I considered the Jews opponents with regard to whom a mutually acceptable, a mutually fair solution must be found,” and he continued, “That solution I envisaged as putting firm soil under the feet of the Jews, so that they would have a place of their own, soil of their own. And I was working in the direction of that solution joyfully. I coöperated in obtaining such a solution, gladly and joyfully, because it was also that kind of a solution which was approved by movements amongst the Jewish people themselves, and I regarded this as the most appropriate solution to this matter.” This was the true reason that the two sides had, as he said, “pulled together” in Vienna, the reason their work had been “based upon mutuality.” It was in the interests of the Jews—though perhaps not all Jews understood this—to get out of the country. “One had to help them, one had to help these [Jewish] functionaries to act, and that’s what I did.” If the functionaries were what Eichmann called “idealists”—that is, Zionists—he respected them, “treated them as equals,” listened to all their “requests and complaints and applications for support,” kept his promises as far as he could. “People are inclined to forget that now,” he added. Who but he, Eichmann, had saved hundreds of thousands of Jews? What but his great zeal and his great gifts of organization had enabled them to escape in time? True, in 1938 he could not foresee the coming Final Solution—as the Nazis called their plan to murder Europe’s Jews—but he had saved those hundreds of thousands; that was a “fact.”

In a sense, one can understand why counsel for the defense did nothing to back up Eichmann’s version of his relations with the Zionists. During the police examination conducted in Jerusalem before his trial, Eichmann admitted—as he had admitted a few years earlier, in Argentina, when he was interviewed by the Dutch journalist Willem S. Sassen—that he “did not greet this assignment with the apathy of an ox being led to his stall,” that he had been very different from those colleagues of his “who had never read a basic book [namely, Theodor Herzl’s “Der Judenstaat” or Adolf Böhm’s “The History of Zionism”], worked through it, absorbed it, absorbed it with interest,” and who therefore lacked “inner rapport with their work.” They were “nothing but office drudges,” for whom everything was decided “by paragraphs, by orders, who were interested in nothing else,” who were precisely those “small cogs” among which, according to the defense, Eichmann himself had been included. If being a small cog meant no more than to give unquestioning obedience to the Führer’s orders, then everybody in the Nazi hierarchy had been a small cog. Even Heinrich Himmler—so we are told by his masseur, a man named Felix Kersten, in his memoirs—had not greeted the Final Solution with great enthusiasm, and Eichmann assured the police examiner in Jerusalem, Captain Avner Less, that his own boss, Heinrich Müller, who commanded the department of the R.S.H.A. (or Head Office for Reich Security) in which Eichmann was a subsection chief, would never have proposed anything so “crude” as “physical extermination.” Obviously, in Eichmann’s eyes the small-cog theory was beside the point. Certainly he had not been as big as the prosecuting attorney, Gideon Hausner, tried to make him. After all, he was not Hitler; nor, for that matter, could he compare himself in importance, as far as the “solution” of the Jewish question went, to Müller, or Reinhardt Heydrich, or Himmler. He was no megalomaniac. But neither was he as small as the defense wished him to be.

Eichmann’s distortions of reality were horrible because of the horrors they dealt with, but in principle they were not very different from the way things are rather generally regarded in post-Hitler Germany. There is, for instance, the case of Franz-Josef Strauss, former Minister of Defense, who recently conducted a Bundestag election campaign against Willy Brandt, the mayor of West Berlin. Of Brandt, who had been a refugee in Norway during the Hitler period, Strauss asked a widely publicized and apparently very successful question: “What were you doing those twelve years outside Germany? We know what we were doing here in Germany.” This question was received by the German public without anybody’s batting an eye, let alone reminding Herr Strauss that what the Germans in Germany were doing during these years had become notorious indeed. The same “innocence” is to be found in a recent casual remark by a respected and respectable German literary critic, who was probably never a Party member; reviewing a study of literature in the Third Reich, he said that its author was one of “those intellectuals who at the outbreak of barbarism deserted us without exception.” This author was a Jew, and was expelled by the Nazis. Incidentally, the very word “barbarism,” today so frequently applied by Germans to the Hitler period, is a distortion of reality; it is as though various intellectuals, whether Jewish or non-Jewish, had fled a country that was no longer “refined” enough for them.

Eichmann, on the other hand, could have cited certain indisputable facts to back up his story if his memory had not been so bad, or if the defense had helped him. For, to quote the publicist Hans Lamm, “it is indisputable that during the first stages of their Jewish policy the National Socialists thought it proper to adopt a pro-Zionist attitude,” and it was during these first stages that Eichmann learned his lessons about Jews. Eichmann was by no means alone in taking this “pro-Zionism” seriously; it was taken seriously by the German Jews themselves, who thought that the Nazis would be satisfied if “assimilation” were to be undone by a new process of “dissimilation,” and who thus flocked to join the ranks of the Zionist movement. This did not necessarily mean that they wished to emigrate to Palestine; it was more a matter of pride. “Wear with Pride the Yellow Star” was the most popular slogan of these years; coined by Robert Weltsch, editor-in-chief of Die Jüdische Rundschau, it expressed the general emotional atmosphere. The polemical point in the slogan, which was formulated more than six years before the Nazis actually forced the Jews to wear as a badge a six-pointed yellow star on a white ground, was directed against the Assimilationists and everyone else who refused to be reconciled to the new “revolutionary development”—all those who, according to a German Zionist publication, “were always behind the times” (“die ewig Gestrigen”). The slogan was recalled at the trial, with a good deal of emotion, by witnesses from Germany. They forgot to mention that Weltsch himself, a highly distinguished journalist, has said in recent years that he would never have issued his slogan if he had been able to foresee developments.

Quite apart from all slogans and ideological quarrels, though, it was in those years a fact of everyday life that only Zionists had any chance of negotiating with the German authorities, for the simple reason that the Zionists’ chief Jewish adversary, the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith, to which ninety-five per cent of organized Jews in Germany then belonged, specified in its bylaws that its chief task was the “fight against anti-Semitism.” The Central Association had suddenly become by definition an organization “hostile to the state,” and would have been persecuted—which it was not—if it had ever dared do what it was supposed to do. Hitler’s rise to power appeared to the Zionists during its first few years chiefly as “the decisive defeat of assimilationism.” Hence, the Zionists could, for a time, at least, engage in a certain amount of non-criminal coöperation with the Nazi authorities; the Zionists, too, believed that “dissimilation,” combined with the emigration to Palestine of Jewish youngsters—and, they hoped, Jewish capitalists—could be a “mutually fair solution.” At the time, many German officials held this opinion. To be sure, no prominent Nazi ever spoke publicly in this vein; from beginning to end, Nazi propaganda was fiercely, unequivocally, uncompromisingly anti-Semitic, and eventually nothing counted but what those people who were still without experience in the mysteries of totalitarian government dismissed as “mere propaganda.” There existed in those first years a mutually highly satisfactory agreement between the Nazi authorities and the Jewish Agency for Palestine (an international organization set up in 1922, with headquarters in Jerusalem)—a Ha’avarah, or Transfer Agreement, which provided that an emigrant to Palestine could transfer his money there in German goods and exchange them for pounds upon arrival. It was soon the only legal way for a Jew to take all his money with him (the alternative then being the establishment of a blocked account, which could subsequently be sold abroad at a loss of between fifty and ninety-five per cent). The result was that in the late thirties, when American Jews were taking great pains to organize a boycott of German merchandise, Palestine, of all places, was swamped with goods “made in Germany.”

Of greater importance for Eichmann than the German Zionists or the Jewish Agency for Palestine were emissaries from Palestine, who, without taking orders from either of these bodies, at that time approached the Gestapo and the S.S. on their own initiative. They came in order to enlist help for the illegal immigration of Jews into British-ruled Palestine, and both the Gestapo and the S.S. were helpful. In Vienna, the emissaries negotiated with Eichmann, as head of the Center for Jewish Emigration, and they reported that he was “polite” and “not the shouting type,” and that he even provided them with farms and other facilities for setting up vocational training camps for prospective immigrants. (“On one occasion, he expelled a group of nuns from a convent to provide a training farm for young Jews,” they noted, and on another “a special train” was made available “and Nazi officials accompanied” a group of emigrants, ostensibly headed for Zionist training farms in Yugoslavia, in order to see them safely across the border.) According to the story told by Jon and David Kimche, in “The Secret Roads: The ‘Illegal’ Migration of a People, 1938-1948,” with—to quote their introduction—“full and generous coöperation from all the chief actors,” these Jews from Palestine spoke a language not totally different from that of Eichmann himself. They operated outside the official framework, having been sent by the Kibbutzim, Palestine’s communal settlements, and they were not interested in rescue operations. (“That was not their job.”) They wanted to select “suitable material,” and their chief enemy (prior to the extermination program) was not those who made life impossible for Jews in Germany and Austria but those who barred access to the new homeland; that is, the enemy was definitely Britain, not Germany. Since, carrying special British passports, they enjoyed the protection of the mandatory power, they were indeed in a position to deal with the Nazi authorities on a footing amounting to equality, which native Jews were not; they were probably among the first Jews to talk openly about mutual interests and were certainly the first to be given permission “to pick young Jewish pioneers” from among the Jews in the prewar concentration camps. They were unaware, of course, of the sinister implications of this deal, which still lay in the future—when Jewish officials prepared the lists of deportees for the Nazi authorities—but they, like Eichmann, somehow believed that if it was a question of selecting Jews for survival, the Jews should do the selecting themselves. It was this fundamental error in judgment that eventually led to a situation in which the non-selected majority of Jews inevitably found themselves confronted with two enemies—the Nazi authorities and the Jewish authorities. As far as the Viennese episode is concerned, Eichmann’s preposterous claim to have saved hundreds of thousands of Jewish lives, which was laughed out of court, finds strange support in the considered judgment of Jon and David Kimche: “Thus what must have been one of the most paradoxical episodes of the entire period of the Nazi regime began: the man who was to go down in history as one of the arch-murderers of the Jewish people entered the lists as an active worker in the rescue of Jews from Europe.”

Eichmann’s trouble was that he remembered none of the facts that might have supported, however faintly, his incredible story, while the learned counsel for the defense probably did not even know that there was anything to remember. (Dr. Servatius could have called as witnesses the former agents of Aliyah Beth, as the organization for illegal immigration into Palestine was called; they certainly still remembered Eichmann, and they were still living in Israel.) Eichmann’s memory functioned only in respect to things that had had a direct bearing upon his career. Thus, he remembered a Palestinian functionary who had visited him in Berlin in 1937 and told him about life in the communal settlements, and whom he had twice taken out to dinner, because this visit ended with a formal invitation to Palestine, where the Jews would show him the country. He was delighted; no other Nazi official had been able to go “to a distant foreign land,” and he received permission to make the trip. The judgment concluded that he had been sent “on an espionage mission,” which no doubt was true, but did not contradict the story Eichmann told. (Nothing came of the enterprise. Eichmann, together with a journalist from his office named Herbert Hagen, got as far as Egypt, and the British authorities there denied them entry permits for Palestine. According to Eichmann, “the man from the Haganah”—the Jewish military organization that later formed the nucleus of the Israeli Army—came to see them in Cairo, and what he told them there eventually became the subject of “a thoroughly negative report,” which he and Hagen were ordered by their superiors to write, in the form of a memorandum, and which was duly published.)

Apart from such minor triumphs, Eichmann remembered only moods and the catch phrases that he had thought up to go with them, and from Vienna he remembered no more than the general atmosphere and how “elated” he had felt. In view of his astounding virtuosity in never discarding a mood and its catch phrase once and for all when they became incompatible with a new era, which required different moods and different catch phrases—a virtuosity that he demonstrated over and over during the police examination—one is tempted to believe in his sincerity when he spoke of his period in Vienna as an idyll. Because of the complete lack of consistency in his thoughts and his sentiments, this possible sincerity would not have been weakened by the fact that his year in Vienna occurred after the Nazi regime had abandoned its pro-Zionist attitude. It was a characteristic of the Nazi movement to keep moving, to become more radical every month, but one of the outstanding characteristics of its members was that psychologically they tended to be always one step behind the movement—that they had the greatest difficulty in keeping up with it. As Hitler used to phrase it, they could not “jump over their own shadow.”

But, as before, it was not objective facts like this that made the possibility of Eichmann’s sincerity seem so absurd; once again, it was his own faulty memory. There were certain Jews in Vienna whom he recalled very vividly, but they were not the Palestinian emissaries who might have backed up his story. Not at all. They were Dr. Josef Löwenherz and Kommerzialrat (Commercial Councillor) Bertold Storfer. Dr. Löwenherz, who after the war wrote a very interesting memorandum about his negotiations with Eichmann (this was one of the few new documents produced by the trial; parts of it were shown, during the police examination, to Eichmann, and he declared himself in complete agreement with its main statements), was the first Jewish functionary who actually organized a whole Jewish Community into an institution that was at the service of the Nazi authorities—the Viennese Community, in 1938. And he was one of the very, very few such functionaries who were able to reap the reward for their services; he was permitted to stay in Vienna until the end of the war, when he emigrated to England and then to the United States. (He died in 1961.) Storfer eventually died in Auschwitz, but this certainly was not Eichmann’s fault. The Palestinian emissaries having become too independent, Storfer replaced them as an emigration expert, and his task, assigned to him by Eichmann, was to organize some illegal group emigrations of Jews to Palestine without the help of the Zionists. Storfer was no Zionist and had shown no interest in Jewish affairs prior to the arrival of the Nazis in Austria. Still, with Eichmann’s help, Storfer succeeded in getting some thirty-five hundred Jews out of Europe, in 1940, when half of Europe was occupied by the Nazis, and it appears that he did his best to clear things with the Palestinians. (That is probably what Eichmann had in mind when he made the cryptic remark: “Storfer never betrayed Judaism, not with a single word, not Storfer.”) A third Jew whom Eichmann never failed to mention in recalling his prewar activities was Dr. Paul Eppstein, who was in charge of emigration in Berlin during the last years of the Reichsvereingung—a Nazi-appointed Jewish central organization, not to be confused with the authentically Jewish Reichsvertretung, which was dissolved in July, 1939. Dr. Eppstein was appointed by Eichmann to serve as Judenältester (Jewish Elder) in Theresienstadt, the concentration camp for privileged German Jews, and he was shot there in 1944.

In other words, the only Jews whom Eichmann remembered were those who had been completely in his power. He had forgotten not only the Palestinian emissaries but also various Berlin acquaintances, whom he had known well when he was still engaged in intelligence work and had no executive powers. For instance, he never mentioned Dr. Franz Meyer, a former member of the Executive of the Zionist Organization in Germany, who came to testify for the prosecution about his contacts with the accused from 1936 to 1939. To some extent, Dr. Meyer confirmed Eichmann’s own story: In Berlin, the Jewish functionaries could “put forward complaints and requests,” and there was a kind of coöperation (sometimes “we came to ask for something, and there were times when he demanded something from us”); Eichmann at that time “was genuinely listening to us and was sincerely trying to understand the situation;” his behavior was “correct.” (“He used to address me as ‘Mister’ and to offer me a seat.”) But by February, 1939, all this had changed. Eichmann had summoned the leaders of German Jewry to Vienna in order to show them his new methods of “forced emigration.” And there he was, sitting in a large room on the ground floor of the Rothschild Palais, recognizable, of course, but completely changed: “I immediately [Dr. Meyer recalled] told my friends that I did not know whether I was meeting the same man. So terrible was the change. . . . Here I met a man who comported himself as a master of life and death. He received us with insolence and rudeness. He did not let us come near his desk. We had to remain standing.” The prosecution and the judges were in agreement that Eichmann underwent a genuine and lasting personality change when, in 1938, he was promoted to a post with executive powers. But the trial showed that he sometimes had what, in another context, he had referred to as “relapses,” and that the matter cannot have been as simple as that. One witness testified about an interview with him at Theresienstadt in March, 1945, when Eichmann once again showed himself to be much interested in Zionist affairs. (The witness was a member of a Zionist youth organization and held a certificate of entry for Palestine. The interview was “held in very pleasant language and the attitude was quite kind and respectful.”)

Whatever doubts there may be about Eichmann’s personality change in Vienna, there is no doubt that this appointment marked the real beginning of his career. Between 1937 and 1941, when he was made head of IV-B-4, the Gestapo subsection dealing with Jewish matters, he won four promotions; within fourteen months he advanced from Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) to Obersturmführer (first lieutenant) to Hauptsturmführer (captain), and in another year and a half he was made Sturmbannführer (major) and then Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel). The last promotion took place in October of 1941, three months after he was assigned the role in the Final Solution that was to land him in the District Court of Jerusalem. But after this promotion, to his great grief, he “got stuck;” as he explained it, there was no higher grade obtainable in the section in which he worked. This he could not know, however, during the three years when he climbed quicker and higher than he had ever anticipated. In Vienna, he showed his mettle, and thereafter he was recognized not merely as an expert on “the Jewish question” (meaning the intricacies of Jewish, and especially Zionist, organizations) but as an “authority” on emigration and evacuation, as the “master” who knew how to make people move. His greatest triumph came shortly after the Kristallnacht, or Night of Broken Glass, in November, 1938, which had made German Jews frantic in their desire to escape. Field Marshal Hermann Göring decided, probably acting upon a recommendation by Heydrich, to establish in Berlin a Reich Center for Jewish Emigration, and in a letter containing his directives Eichmann’s Viennese office was specifically mentioned as the model to be used in the setting up of this central authority. It was not Eichmann, however, who was appointed to head the new office but his future boss, Heinrich Müller, who had just been taken away by Heydrich from his job as a regular Bavarian police officer (he was not even a member of the Party) and called to the Gestapo in Berlin, because he was known to be an authority on the Soviet Russian police system. For Müller, too, this was the beginning of a successful career, though he had to start with a comparatively small assignment. (Müller, who was not prone to boasting, like Eichmann, and was known for his “sphinxlike conduct,” succeeded in disappearing altogether; nobody knows his whereabouts, though there are rumors that East Germany has engaged the services of this Russian-police expert.)

In March, 1939, Hitler moved into Czechoslovakia and welded Bohemia and Moravia into a German protectorate. Eichmann was immediately appointed to set up an emigration center for Jews in Prague. (“In the beginning I was not too happy to leave Vienna, for if you have installed such an office and if you see how everything runs smoothly and in good order, you don’t like to give it up,” Eichmann told the police examiner.) Prague was somewhat disappointing, although the system was the same in both cities: “The functionaries of the Czech Jewish organizations went to Vienna and the Viennese people came to Prague, so that I did not have to intervene at all. The model in Vienna was simply copied and carried to Prague. Thus the whole thing got started automatically.” But the Prague center was much smaller, and “I regret to say there were no people of the calibre and the energy of a Dr. Löwenherz.” But these (as it were) personal reasons for discontent were minor compared to mounting difficulties of another kind. Hundreds of thousands of Jews had left their homelands in a matter of a few years, and millions waited behind them, for the Polish and Rumanian governments now left no doubt in their official proclamations that they, too, wished to be rid of their Jews. (They could not understand why the world should get indignant if they followed in the footsteps of what one of their officials called a “great and cultured nation.”) The opportunities for Jews to find refuge within Europe had been exhausted long before, and now the avenues for overseas emigration clogged up, so even under the best of circumstances—that is, even if war had not interfered with his program—Eichmann would hardly have been able to duplicate “the Viennese miracle” in Prague. He knew this very well. Certainly Eichmann could not have been expected to greet his next appointment with any great enthusiasm. War broke out on September 1, 1939, and one month later Eichmann was called back to Berlin to succeed Müller as head of the Reich Center for Jewish Emigration. A year before, this would have been a real promotion, but now was the wrong moment. No one in his senses could possibly think any longer of a solution of the Jewish question in terms of forced emigration; not only was there the difficulty of getting people from one country to another in wartime but now, through the conquest of Polish territories, the Reich had acquired two or two and a half million more Jews. It is true that the Hitler government was still willing to let its Jews go (the order that stopped all Jewish emigration did not come until the fall of 1941), and if the Final Solution had been decided upon, nobody had as yet given orders to that effect, though Jews in the East already were concentrated in ghettos and were also being liquidated by the Einsatzgruppen—the mobile killing units of the S.S. that operated in the rear of the Army. It was only natural that emigration, however smartly organized in Berlin in accordance with Eichmann’s “assembly line” principle, should peter out by itself—a process Eichmann described by saying, “It was like pulling teeth; tendency: listless, I would say, on both sides. On the Jewish side because it was really difficult to obtain emigration possibilities to speak of, and on our side because there was no bustle and no rush, no coming and going of people. There we were, sitting in a great and mighty building, amid a yawning emptiness.” Evidently, if Jewish matters, Eichmann’s specialty, remained a matter of emigration, he would soon be out of a job.

It was not until the outbreak of the war that the Nazi regime became openly totalitarian and openly criminal. One of the most important steps in this direction, from an organizational point of view, was a decree, signed by Himmler on September 27, 1939, that fused the Security Service of the S.S., to which Eichmann had belonged since 1934, and which was a Party organ, with the regular Security Police of the state, in which the Secret State Police, or Gestapo, was included. The result of the merger was called the Head Office for Reich Security (the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, or R.S.H.A.), and Heydrich was its first chief; after Heydrich’s death, in 1942, an old acquaintance of Eichmann’s from Linz, Dr. Ernst Kaltenbrunner, took over. By Himmler’s decree, all police officials—not only of the Gestapo but also of the Criminal Police and the Order Police—received S.S. titles corresponding to their previous ranks, whether or not they were Party members, and this meant that overnight one of the principal arms of the old civil service was incorporated into the most radical section of the Nazi hierarchy. As far as I know, no one protested, or resigned his job. (Himmler, the head and founder of the S.S., had since 1936 been Chief of the German Police as well, but the two apparatuses had nevertheless remained separate until now.) The R.S.H.A., moreover, was only one of twelve Head Offices in the S.S., the most important of which, in the present context, were the Head Office of the Order Police (the Hauptamt Ordnungspolizei), under General Kurt Daluege, which was responsible for the rounding up of Jews, and the Head Office for Economy and Administration (the Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt, or W.V.H.A.), under Obergruppenführer Oswald Pohl, which was in charge of concentration camps and was later to be in charge of the “economic” side of the extermination.

The “objective” attitude—talking about concentration camps in terms of “administration” and about extermination camps in terms of “economy”—was typical of S.S. habits of thought, and was something that Eichmann, at the time of his trial, was still very proud of. By its “objectivity” (“Sachlichkeit”), the S.S. dissociated itself from such “emotional” types as Streicher (that “most unrealistic fool,” as Eichmann called him) and also from certain “Teutonic-Germanic party bigwigs who behaved as though they were clad in horns and pelts,” to quote Eichmann in the police examination. Since Eichmann did not like such nonsense at all, he admired Heydrich greatly, and he felt a lack of sympathy with Himmler because, among other things, the “Reichsführer S.S. and Chief of the German Police” (as Eichmann invariably referred to him), though boss of all the S.S. Head Offices, had permitted himself “at least for a long time to be influenced by it.” During the trial, however, it was not the accused who succeeded in carrying off the prize in “objectivity;” it was the counsel for the defense. A tax and business lawyer from Cologne who had never joined the Nazi Party, Dr. Servatius was nevertheless able to teach the court a lesson in what it means not to be “emotional” that no one who heard him is likely to forget. The great moment—one of the few great ones in the whole trial—occurred during the short oral plaidoyer of the defense, after which the court withdrew for four months to write its judgment. Servatius declared the accused innocent of charges bearing on his responsibility for “the collection of skeletons, sterilizations, killing by gas, and similar medical matters,” whereupon Judge Halevi interrupted him. “Dr. Servatius,” the Judge said, “I assume you made a slip of the tongue when you said that killing by gas was a medical matter,” at which point Servatius replied, “It was indeed a medical matter, since it was prepared by physicians; it was a matter of killing, and killing, too, is a medical matter.” And, perhaps to make absolutely sure that the judges in Jerusalem would not forget how Germans—ordinary Germans, not former members of the S.S., or of the Nazi Party—even today can regard acts that in other countries are called murder, he repeated the phrase in his “Comments on the Judgment of the First Instance,” prepared for the review of the case before the Supreme Court, stating that not Eichmann but one of his men, Rolf Günther, “was always engaged in medical matters.”

Each of the Head Offices was divided into sections and subsections, and the R.S.H.A. contained six (later seven) main sections. Section IV, headed by Müller, who was an S.S. Gruppenführer, or major general (the equivalent of the rank he had held in the Bavarian Police), was the bureau of the Gestapo. Its task was defined as “combatting opponents hostile to the state,” of whom there were two categories, and who were therefore dealt with by two subsections: Subsection IV-A, which handled matters concerned with Communism, Sabotage, Liberalism, and Assassinations, and Subsection IV-B, which handled matters concerned with Sects; that is, Catholics, Protestants, Freemasons, and Jews. Each of the categories in this subsection received an office of its own, designated by an arabic numeral, and Eichmann, in March of 1941, was appointed to the desk of IV-B-4 in the R.S.H.A. Since his immediate superior, the head of IV-B, turned out to be a nonentity, his real superior was always Müller. Müller’s superior was Heydrich, and later Kaltenbrunner, each of whom was, in his turn, under the command of Himmler, who received his orders directly from Hitler.

In addition to his twelve Head Offices, Himmler presided over another organizational setup, which also played an enormous role in the carrying out of the Final Solution. This consisted of the Higher S.S. and Police Leaders, who were in command of regional organizations; their chain of command did not link them with the R.S.H.A.—they were directly responsible to Himmler—and they always outranked Eichmann and the men at his disposal. The Einsatzgruppen, on the other hand, were under the command of Heydrich and the R.S.H.A.—which, of course, does not mean that Eichmann had anything to do with them. The commanders of the Einsatzgruppen also invariably held a higher rank than Eichmann. Technically and organizationally, Eichmann’s position was not very high; his post turned out to be such an important one only because the Jewish question, for purely ideological reasons, acquired a greater importance with every day and week and month of the war, until, from 1943 on, in the years of defeat, it had grown to fantastic proportions. In these years, his was still the only office that officially dealt with nothing but “the opponent, Jewry,” but actually he had lost his monopoly, because by then all offices and apparatuses—state and Party, Army and S.S.—were busy “solving” the Jewish problem. Even if we concentrate our attention only upon the police machinery and disregard all the other offices, the picture is absurdly complicated, since we have to add to the Einsatzgruppen and to the Higher S.S. and Police Leader Corps the commanders and the inspectors of the Security Police and the Security Service. Each of these several groups belonged to a separate chain of command that ultimately reached Himmler, but they were equal with respect to each other and nobody belonging to one group owed obedience to a superior officer of another group. The prosecution, it must be admitted, was in a most difficult position in that each time it wanted to pin some specific responsibility on Eichmann, it was obliged to find its way through this labyrinth of parallel institutions. (If the trial were to take place today, this task would be much easier, for the political scientist Raul Hilberg, in his book “The Destruction of the European Jews,” published in Chicago in 1961, has succeeded in presenting the first clear description of this incredibly complicated machinery of destruction.) Furthermore, it must be remembered that all these organs, wielding enormous power, were in fierce competition, which was anything but a help to their victims, since their ambition was always the same—to kill as many Jews as possible. This competitive spirit, which, of course, inspired in each man a great loyalty to his own outfit, has survived the war, only now it works in reverse: it has become each man’s desire to exonerate his own outfit at the expense of all the others. This was the explanation that Eichmann gave when he was confronted with the memoirs of Rudolf Höss, Commandant of Auschwitz, in which Eichmann is accused of doing certain things that he claimed he never did and was in no position to do. He admitted easily enough that Höss had no personal reason for saddling him with deeds of which he was innocent, since their relationship had always been quite friendly; Höss, he insisted—in vain—wanted to exculpate his own outfit, the Head Office for Economy and Administration, by putting all the blame on the R.S.H.A. Something of the same sort happened in Nuremberg, where the various accused presented a nauseating spectacle by accusing each other (though none of them blamed Hitler). Still, this was not done merely to enable a man to save his own neck at the expense of somebody else’s; the men on trial represented altogether different organizations, which had a long-standing, deeply ingrained hostility to one another. Eichmann always tried to shield Müller and Heydrich, and Kaltenbrunner as well, even though Kaltenbrunner had treated him quite badly. No doubt, one of the chief mistakes of the prosecution was that its case relied too heavily on statements of former high-ranking Nazis, dead or alive; it did not see, and perhaps could not be expected to see, how dubious these documents were as sources for the establishment of facts. The judgment itself, in its evaluation of the damning testimonies of other Nazi criminals, paid no attention to this question of loyalties, but it did take into account the fact that (in the words of one of the defense witnesses) “it was customary at the time of the war-crime trials to put as much blame as possible on those who were absent or believed to be dead.”

When Eichmann entered his new office, in charge of Subsection B-4 of Section IV of the R.S.H.A., he was still confronted with this uncomfortable dilemma; namely, that, on the one hand, “forced emigration” was the official formula for the solution of the Jewish question, and, on the other hand, emigration was no longer possible. For the first (and almost the last) time in his life in the S.S., he was forced by circumstances to take an initiative—to see if he could not, in his words, “give birth to an idea.” According to the account he gave the police examiner, he was blessed with three ideas. All three of them, he had to admit, came to naught. Everything he tried on his own invariably went wrong—nothing but frustration. It was a hard-luck story if ever there was one. The inexhaustible source of troubles, as he saw it, was that he and his men were never left alone—that all these other state and Party offices wanted their share in the “solution,” with the result that a veritable army of “Jewish experts” had cropped up everywhere and were falling over themselves in their efforts to be first in a field of which they knew nothing. For these people Eichmann had the greatest contempt, partly because they were Johnnies-come-lately, partly because they tried to enrich themselves in the course of their work, and often succeeded, and partly because they were ignorant, not having read, as he had, any “basic books.”

Eichmann’s three dreams turned out to have been inspired by the two “basic books” (Herzl and Böhm), but it was also revealed that two of the three were definitely not his ideas at all, and with respect to the third—well, “I do not know any longer whether it was Stahlecker [Franz Stahlecker, his superior in Vienna and Prague] or myself who gave birth to the idea; anyhow, the idea was born.” This last idea was the first, chronologically. It was the “idea of Nisko,” and its failure was for Eichmann the clearest possible proof of the evil of interference—the guilty person in this case being Hans Frank, Governor General of the area in Poland the Nazis designated the General Government. In order to understand the Nisko plan, we must remember that right after the conquest of Poland, the Polish territories were divided between Germany and Russia. The German part consisted of the Western regions, which were incorporated into the Reich, and the Eastern area, including Warsaw (Russia got an area still farther east), which at first was treated as occupied territory and later became the General Government. As the solution of the Jewish question at this time was still “forced emigration,” with the aim of making Germany judenrein (Jewclean), it was natural that Polish Jews in the Western regions, together with whatever Jews remained in other parts of the Reich, should be shoved into the General Government, which, whatever it may have been, was not considered to be part of the Reich. By December, 1939, evacuations eastward had started, and over the next two years roughly a million Jews—six hundred thousand from the incorporated area and four hundred thousand from the Reich proper—arrived in the General Government. If Eichmann’s version of the Nisko adventure is true—and there is no reason not to believe him—he or, more likely, his Prague and Vienna superior, S.S. Brigadeführer Dr. Franz Stahlecker, must have anticipated the eastward deportations by several months. This Dr. Stahlecker (Eichmann was always careful to give him this title) was in Eichmann’s opinion a very fine man, educated, full of reason, and “free of hatred and free from chauvinism of any kind;” in Vienna, he used to shake hands with the Jewish functionaries. A year and a half later, in the spring of 1941, this educated gentleman was appointed Commander of Einsatzgruppe A, and afterward he managed to kill by shooting, in little more than a year (he himself was killed in action in 1942), two hundred and fifty thousand Jews—as he proudly reported to Himmler himself, rather than to his own chief, Heydrich. But that came later, and now, in September, 1939, while the German Army was still busy occupying the Polish territories, Eichmann and Dr. Stahlecker began to think “privately” about how the Security Service might get its share of influence in the East. What they needed was, as Eichmann later put it, “an area as large as possible in Poland, to be carved off for the erection of an autonomous Jewish state in the form of a protectorate,” for “this could be the solution.” And off they went, on their own initiative, without orders from anybody, to reconnoitre. They went to the Radom district, on the San River, not far from the Russian border, and they “saw a huge territory, the San River, villages, market places, small towns,” and “we said to ourselves: That is what we need and why should one not resettle Poles for a change, since people are being resettled everywhere?” This, they said, would be “the solution of the Jewish question”—firm soil under their feet—at least for some time. Everything seemed to go very well at first. They spoke to Heydrich, and Heydrich agreed with what they said, and told them to go ahead. It happened—though Eichmann, in Jerusalem, had completely forgotten it—that their project fitted in very well with Heydrich’s over-all plan at this stage for the solution of the Jewish question. On September 21, 1939, he had called a meeting of the heads of departments of the R.S.H.A. and the Einsatzgruppen (they were already operating in Poland) and had given general directives for the immediate future: Jews were to be concentrated in ghettos; Councils of Jewish Elders were to be established; and all Jews were to be deported to the General Government. Eichmann had attended this meeting as representative of the Center for Jewish Emigration—as was proved at the trial by means of the minutes, which Bureau 06 of the Israeli Police had discovered in the United States National Archives, in Washington. Hence, Eichmann’s (or, more probably, Stahlecker’s) initiative amounted to no more than a concrete plan for carrying out Heydrich’s directives. And now thousands of people, chiefly from Austria, were deported helter-skelter into this godforsaken place, which, an S.S. officer explained to them, “the Führer has promised the Jews [as] a new homeland.” The officer went on to tell them, “There are no dwellings; there are no houses. If you build, there will be a roof over your heads. There is no water; the wells all around carry disease; there is cholera, dysentery, and typhoid. If you bore and find water, you will have water.” As one can see, “everything looked marvellous,” Eichmann said, except that the S.S. expelled some of the Jews from this paradise into Russia, and others soon had the good sense to escape of their own volition. But thereafter, Eichmann complained, “the obstructions began from the side of Hans Frank”—whom they had forgotten to inform, although this was “his” territory. “Frank complained in Berlin, and a great tug of war started. Frank wanted to solve his Jewish question all by himself. He did not want to receive any more Jews in his General Government. Those who had arrived should, he said, disappear immediately.” And they did disappear; they were actually repatriated, which had never happened before and never happened again, and those who returned to Vienna were registered in the police records as “returning from vocational training”—a curious relapse into the pro-Zionist stage of the movement.

Eichmann’s eagerness to acquire some territory for “his Jews” is best understood in terms of his own career. The Nisko plan was “born” during the time of his rapid promotion, and it is more than likely that he saw himself as the future “Governor General” (like Hans Frank in Poland) or “Protector” (like Heydrich in Czechoslovakia) of a “Jewish state.” The utter failure of the whole enterprise, however, must have taught him a lesson about the possibilities and the desirability of “private” initiative. And since he and Stahlecker had acted within the framework of Heydrich’s directives and with Heydrich’s explicit consent, this unique repatriation of Jews, which was so clearly a temporary defeat for police and S.S., must also have taught him that the steadily increasing power of his own outfit did not amount to omnipotence—that the Ministries and the other Party institutions were quite prepared to fight for their own shrinking power.

Eichmann’s second attempt to “put firm ground under the feet of the Jews” concerned Madagascar. It was a plan to evacuate four million Jews from Europe to the French island off the southeast coast of Africa—an island with a native population of four million and an area of 227,678 square miles of poor land—and it had originated in the Foreign Office. It was eventually transmitted to the R.S.H.A., because, in the words of Dr. Martin Luther, who was in charge of Jewish affairs in the Wilhelmstrasse, only the police “possessed the experience and the technical facilities to execute an evacuation of Jews en masse and to guarantee the supervision of the evacuées.” The “Jewish state” was to have a police governor, under the jurisdiction of Himmler. The project itself had an odd history. Eichmann, confusing Madagascar with Uganda, always claimed to have dreamed “a dream once dreamed by the Jewish protagonist of the Jewish state idea, Theodor Herzl,” and it is true that his dream had been dreamed before—first by the Polish government, which in 1937 went to much trouble to look into the idea, only to find out that it would be quite impossible to ship its own three million Jews there without killing them, and, second, by the French Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet, who had the more modest scheme of shipping France’s foreign Jews, numbering between one hundred thousand and two hundred thousand, to the French colony. (In 1938, Bonnet consulted his German opposite number, Joachim von Ribbentrop, on the matter.) As for Eichmann, he was ordered in the summer of 1940, when his emigration business had come to a complete standstill, to work out a detailed plan for the evacuation of four million Jews to Madagascar, and this project seems to have occupied most of his time until the invasion of Russia, a year later. (Four million was a low figure for making Europe judenrein. It obviously did not include three million Polish Jews, who, as everybody knew, had been in the process of being massacred ever since the first days of the war.) That anybody except Eichmann and some other lesser luminaries ever took the whole thing seriously seems unlikely, for—apart from the fact that the territory was known to be unsuitable, not to mention the fact that it was, after all, a French possession—the plan would have required shipping space for four million people in the middle of a war and at a moment when the British Navy was in control of the Atlantic. The Madagascar plan was always intended to serve as a cloak under which the preparations for the physical extermination of the Jews of Western Europe could be carried forward (no such cloak was needed, evidently, for the extermination of Polish Jews), and its great advantage with respect to the army of trained anti-Semites, who, try as they might, consistently found themselves one step behind the Führer, was that it familiarized all concerned with the preliminary notion that nothing less than complete disappearance from Europe would do—no special legislation, no “dissimilation,” no ghettos would suffice. When, a year later, the Madagascar project was declared to have become “obsolete,” everybody was psychologically—and logically—prepared for the next step: Since there existed no territory to which one could evacuate all Jews, the only solution was extermination.

Not that Eichmann ever suspected the existence of such sinister plans. What brought the enterprise to naught, he was convinced, was lack of time, and time had been wasted through the never-ending interference from other offices. In Jerusalem, both the police and the court tried to shake him out of this state of mind in which he could only recall the interference and complain about it. They confronted him with two documents concerning meetings that Heydrich had called in September, 1939; one of them, a teletyped letter written by Heydrich and containing certain directives to the Einsatzgruppen, distinguished for the first time between a “final aim requiring longer periods of time” and to be treated as “top-secret,” and “the stages for achieving this final aim to be carried out within short periods.” The phrase “final solution” did not yet appear, and the document is silent about the meaning of the phrase “final aim.” Hence, Eichmann could have said: All right, the “final aim” was his Madagascar project, which at this time was being kicked around all German offices; for a mass evacuation, the concentration of all Jews was a necessary preliminary “stage.” But Eichmann, after reading the document carefully in Jerusalem, was immediately convinced that “final aim” could only mean “physical extermination,” and concluded that “this basic idea was already rooted in the minds of the higher leaders, or the men at the very top.” But if this was so, he would have to admit that the Madagascar project could not have been more than a hoax. Well, he did not; he never changed his Madagascar story, and he probably just could not change it. It was as though this story ran along a different tape in his memory, and this taped memory showed itself to be proof against reason and argument and information and insight of any kind. His memory informed him that there had existed a lull in the activities against the Jews of Western and Central Europe between the outbreak of the war (Hitler, in his speech to the Reichstag of January 30, 1939, had “prophesied” that war would bring the “annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe”) and the invasion of Russia. To be sure, even then the various offices in the Reich and in the occupied territories were doing their best to eliminate “the opponent, Jewry,” but there was no unified policy; it seemed as though every office had its own “solution” and might be permitted to apply it or to pit it against the rival solutions. Eichmann’s solution was a police state, and for that he needed a sizable territory. All his “efforts failed because of the lack of understanding of the concerned minds,” because of “rivalries,” quarrels, squabbling, because everybody “vied for supremacy.” And then it was too late; the war against Russia “struck suddenly, like a thunderclap.” That marked the end of his dreams and of “the era of searching for a solution in the interest of both sides.” It also marked, as he recognized in the memoirs he wrote in Argentina, “the end of an era in which there existed laws, ordinances, decrees for the treatment of individual Jews.” And, according to him, it was something more than that; it was the end of his career, and though this sounded rather crazy, in view of his current “fame,” it could not be denied that he had a point. For his outfit, which either in the actuality of “forced emigration” or in the “dream” of a Nazi-ruled Jewish state had been the final authority in all Jewish matters, now, in Eichmann’s words, “receded into the second line so far as the final solution of the Jewish question was concerned, for what was now initiated was transferred to different units, and negotiations were conducted by another Head Office, under the command of the former Reichsführer S.S. and Chief of the German Police.” The different units were the selected groups of killers (the Einsatzgruppen) who operated in the rear of the Army in the East, where their special duty consisted in the massacre of the native civilian population and especially of the Jews; and the other Head Office—as distinguished from the R.S.H.A.—was the W.V.H.A., or Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt (Head Office for Economy and Administration). From the W.V.H.A., Eichmann now received information about the ultimate destination of each shipment of Jews, which was figured out according to the “absorptive capacity” of the various killing centers and also according to the number of slave workers requested by the many industrial enterprises that had found it profitable to establish branches in the neighborhood of some of the death camps. (Apart from the not very important industrial activities of the S.S. itself, such famous German firms as I. G. Farben, the Krupp Werke, and the Siemens-Schuckert Werke had established plants in Auschwitz and near the Lublin death camps. There was excellent coöperation between the S.S. and the businessmen, and Höss, of Auschwitz, testified to very cordial social relations with the local I. G. Farben representatives. As for working conditions, the idea was clearly to kill through labor. According to Raul Hilberg, in “The Destruction of the European Jews,” at least twenty-five thousand Jews out of approximately thirty-five thousand who worked for one of the I. G. Farben plants died.) As far as Eichmann was concerned, the big point was that evacuation and deportation—once of primary importance—were no longer the last stages of the “solution.” His department had become merely instrumental. Hence he had every reason to be, as he put it, “embittered and disappointed” when the Madagascar project was shelved, and the only thing he had to console him was his promotion to Obersturmbannführer, which came in October, 1941.

According to Eichmann’s recollection, the last time he tried something on his own was in September, 1941, three months after the invasion of Russia. This was just after Heydrich, who was still chief of the Security Police and the Security Service, had become Protector of Bohemia and Moravia. To celebrate the occasion, Heydrich had called a press conference in Prague and had promised that in eight weeks the Protectorate would be judenrein. After the press conference, he discussed the matter with those who would have to make his word good—with Stahlecker, who was then local commander of the Security Police in Prague, and with Undersecretary of State Karl Hermann Frank, a former Sudeten leader, who soon after Heydrich’s death, eight months later, succeeded him as Protector. Frank, in Eichmann’s opinion, was a low type—a Jew-hater of “the Streicher kind,” who “didn’t know a thing about political solutions,” and one of those people who “autocratically and, let me say, in the drunkenness of their power simply gave orders and commands.” But otherwise the discussion, at which Eichmann was present, was enjoyable. For the first time, Eichmann recalled, Heydrich showed “a more human side” and admitted, with beautiful frankness, that he had “allowed his tongue to run away with him,” which Eichmann said was “nothing to greatly surprise those who knew Heydrich,” an “ambitious and impulsive character,” who “often let words slip through the fence of his teeth more quickly than he later might have liked.” So Heydrich himself said, “There is the mess, and what are we going to do now?” Eichmann replied, “There exists only one possibility if you cannot retreat from your announcement. Give enough room [in Czechoslovakia] to transfer the Jews of the Protectorate, who now live dispersed.” (A Jewish homeland, a gathering in of the exiles in the Diaspora.) And then, “unfortunately,” Frank—the Jew-hater of the Streicher kind—made a concrete proposal, and that was that the room be provided in the town of Theresienstadt. Whereupon Heydrich, perhaps also in the drunkenness of his power, simply ordered the immediate evacuation of the native Czech population of Theresienstadt, to make room for the Jews. Eichmann was sent there to look things over, and he was disappointed by what he saw. The little Bohemian fortress town on the banks of the Eger was far too small; at best, it could become a transfer camp for a certain percentage of the ninety thousand Jews in Bohemia and Moravia. (For about fifty thousand Czech Jews, Theresienstadt indeed became a transfer camp on the way to Auschwitz; an estimated twenty thousand more reached the same destination directly.) We know from better sources than Eichmann’s imperfect memory that Theresienstadt, from the beginning, was designed by Heydrich to serve as a special ghetto for certain privileged categories of Jews, who would be chiefly, but not exclusively, from Germany—Jewish functionaries, prominent (“famous”) people, Jewish war veterans with high decorations, invalids, the Jewish partners of mixed marriages, and German Jews over sixty-five years of age. (Owing to the presence of the last group, Theresienstadt was nicknamed Altersghetto, or the Old People’s Ghetto.) The town proved too small even for these restricted categories, and in 1943, about a year after its establishment, there began the “thinning out” or “loosening up” (Auflockerung) process by which overcrowding was regularly relieved—shipment to Auschwitz. But in one respect Eichmann’s memory did not deceive him. Theresienstadt was, as he said, the only concentration camp that did not fall under the authority of the W.V.H.A. but remained his own responsibility to the end. Its commanders were men from his own staff, and they were always his inferiors in rank. Theresienstadt, then, was the only camp in which he had at least some of the power that the prosecution in Jerusalem ascribed to him.

Eichmann’s memory, jumping with great ease over the years—he was two years ahead of the sequence of events when he told the police examiner the story of Theresienstadt—was certainly not controlled by the chronological sequence of events, but it was not simply erratic. It was a storehouse, filled with human-interest stories of the worst type. When he thought back to Prague, there emerged the occasion when he was admitted to the presence of the great Heydrich and Heydrich showed himself to have “a more human side.” A few sessions later, he mentioned a trip to Bratislava, in Slovakia, where he happened to be at the time Heydrich was assassinated by two Czech patriots. What he remembered was that he was there as the guest of Sano Mach, Minister of the Interior in the German-established puppet government of Slovakia. (In Slovakia’s strongly anti-Semitic Catholic government, Mach represented the German version of anti-Semitism; he refused to exempt baptized Jews from anti-Jewish legislation, and he was one of the persons chiefly responsible for the wholesale deportations of Slovak Jewry.) Eichmann remembered this because it was unusual for him to receive social invitations from members of governments; this was an honor. Mach, Eichmann recalled, was a nice, easygoing fellow who invited him to bowl with him. Did he really have no other business in Bratislava in the middle of the war than to go bowling with the Minister of the Interior? No, absolutely no other business; he remembered it all very well—how they bowled, and how drinks were served just before the news of the assassination. Four months and fifty-five tapes later, the police examiner came back to this point, and Eichmann told the same story in nearly the same words, adding that this day had been “unforgettable,” because his “superior had been assassinated.” This time, however, he was confronted with a document that said he had been sent to Bratislava to talk over “the current evacuation action against Jews from Slovakia.” He admitted his error at once: “Sure, that was an order from Berlin. . . . They did not send me there to go bowling.” Had he lied twice, with great consistency? Hardly. To evacuate and deport Jews had become routine business; what stuck out was bowling, being the guest of a Minister, and hearing of the death of Heydrich. And it was characteristic of his kind of memory that he could absolutely not recall the year in which this memorable day fell.

Had his memory served him better, he would never have told the Theresienstadt story at all, for all this happened when the era of “political solutions” had passed and the era of the “physical solution” had begun. It happened when, as he was to admit freely and spontaneously in another context, he himself had already been informed of the Führer’s order for the Final Solution. To make a country judenrein at the date when Heydrich promised to do so for Bohemia and Moravia could mean only concentration and deportation to points from which Jews could easily be shipped to the killing centers.

On June 22, 1941, Hitler launched his attack on the Soviet Union, and six or eight weeks later Eichmann was summoned to Heydrich’s office in Berlin. On July 31st, Heydrich had received a letter from Field Marshal Göring, Commander-in-Chief of the Air Force, Prime Minister of Prussia, Plenipotentiary for the Four-Year Plan, and Hitler’s Deputy in the state (as distinguished from the Party) hierarchy. The letter commissioned Heydrich to prepare “the general solution [Gesamtlösung] of the Jewish question within the area of German influence in Europe,” and to submit “a general proposal . . . for the implementation of the desired final solution [Endlösung] of the Jewish question.” At the time Heydrich received these instructions, he had already been—as he was to explain to the High Command of the Army in a letter dated November 6, 1941—“entrusted for years with the task of preparing the final solution of the Jewish problem,” and since the beginning of the war with Russia he had been in charge of the mass killings by the Einsatzgruppen in the East. Heydrich summoned Eichmann and began their interview with “a little speech about emigration” (which had practically ceased, though Himmler’s formal order prohibiting it was not issued until a few months later), and then said, “The Führer has ordered the physical extermination of the Jews.” After that, Eichmann recalled, “very much against his habits, he [Heydrich] remained silent for a long while, as though he wanted to test the impact of his words,” and, Eichmann’s account continued, “I remember it even today. In the first moment, I was unable to grasp the significance of what he had said, because he was so careful in choosing his words, and then I understood, and didn’t say anything, because there was nothing to say any more. For I had never thought of such a thing, such a solution through violence. I lost everything—all joy in my work, all initiative, all interest; I was, so to speak, blown out. And then he told me, ‘Eichmann, you go and see Globocnik [Odilo Globocnik, one of Himmler’s Higher S.S. and Police Leaders in the General Government] in Lublin. . . . The Reichsführer [Himmler] has already given Globocnik the necessary orders. Have a look at what he has achieved in the meantime. I think he uses the Russian tank trenches for the extermination of the Jews.” I still remember that, for I’ll never forget it no matter how long I live, those sentences he said during that interview, which was already at an end.” Actually—as Eichmann still remembered in Argentina but had forgotten by the time he reached Jerusalem, much to his disadvantage, since it concerned the question of his own authority in the actual killing process—Heydrich had said a little more. He had told Eichmann that the whole enterprise was “put under the authority of the S.S. Head Office for Economy and Administration”—that is, not of his own R.S.H.A.—and also that the official code name for extermination was to be “Final Solution.”

Eichmann was by no means among the first to be informed of Hitler’s intention. Heydrich, as he himself said, had been working toward this end for years—presumably since the beginning of the war—and Himmler later claimed to have been told (and to have protested against) this “solution” immediately after the defeat of France, in the summer of 1940. By March, 1941, about five months before Eichmann had his interview with Heydrich, “it was no secret in higher Party circles that the Jews were to be exterminated”—so Viktor Brack, of the Führer Chancellery, testified at Nuremberg. But Eichmann, as he vainly tried to explain in Jerusalem, had never been a member of the higher Party circles; he had never been told more than he needed to know in order to do a specific, limited job. It is true that he was one of the first men in the lower echelons to be informed of this “top-secret” matter, that remained “top-secret” even after the news had spread throughout all the Party and state offices, all business enterprises connected with slave labor, and the entire officer corps (at the very least) of the armed forces. This “secrecy” did have a practical purpose, however. Those who were explicitly told of the Führer Order (as Hitler’s 1941 order for the total extermination of the Jews was called by the Nazis) were no longer mere “bearers of orders” but were advanced to the status of “bearers of secrets,” and a special oath was administered to them. Furthermore, all correspondence referring to the matter was subject to a rigid “language rule,” and, except in the reports from the Einsatzgruppen, it is rare to find documents in which such bald words as “extermination,” “liquidation,” and “killing” occur. The prescribed code names for killing were not only “final solution” but “evacuation” (Aussiedlung) and “special treatment” (Sonderbehandlung); deportation—unless it involved Jews directed to Theresienstadt, in which case it was called “change of residence”—received the names of “resettlement” (Umsiedlung) and “labor in the East” (Arbeitseinsatz im Osten), and the point of these names was that Jews were indeed often temporarily resettled in ghettos and that a certain percentage of them were temporarily used for labor. Under special circumstances, slight changes in the language rules could be made. For instance, a higher official in the Foreign Office once proposed that in all correspondence with the Vatican the killing of Jews be called the “radical solution;” this was ingenious, because the Slovak Catholic puppet government, with whom the Vatican had intervened, had not been, in the view of the Nazis, “radical enough” in its anti-Jewish legislation, having committed the “basic error” of excluding baptized Jews. Only among themselves could the “bearers of secrets” talk in uncoded language, and it is very unlikely that they did so in the ordinary pursuit of their murderous duties—certainly not in the presence of their stenographers and other office personnel. For whatever other reasons the language rules might have been devised, they proved of enormous help in the maintenance of order and sanity in the various, widely branched-out services whose coöperation was essential in this matter. Moreover, the very name “language rule” (Sprachregelung) was itself a code name; it meant what in ordinary language would be called a lie. For when a “bearer of secrets” was sent to meet someone from the outside world (as when Eichmann was sent to show the Theresienstadt ghetto to International Red Cross representatives from Switzerland), he received, together with his orders, his “language rule.” (In this instance, it consisted of a lie about a nonexistent typhus epidemic in the concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen, which the Red Cross men also wished to visit.) The net effect of the language system was not to keep these people ignorant of what they were doing but to prevent them from equating it with their old, “normal” knowledge of murder and lies. Eichmann’s great susceptibility to catchwords and stock phrases, combined with his incapacity for ordinary speech (he being mostly limited to officialese and self-invented clichés), made him, of course, an ideal subject for “language rules.”

The system, however, was not a foolproof shield against reality, as Eichmann was soon to find out. Late in the summer of 1941, he went to the Lublin area to see Brigadeführer Globocnik, as Heydrich had ordered, though not, as the prosecution maintained, “to transmit to him personally the secret order for the physical extermination of the Jews” (which Globocnik certainly knew of before Eichmann did), and he used the phrase “Final Solution” as a kind of password with which to identify himself. (A similar assertion by the prosecution, which showed to what a degree it had got lost in the bureaucratic labyrinth of the Third Reich, referred to Höss, Commandant of Auschwitz, who, it believed, had also received the Führer Order through Eichmann. This error was at least mentioned by the defense as being “without corroborative evidence.” Actually, Höss himself had testified at his own trial, in Poland, that he had received his orders directly from Himmler, in June, 1941, and added that Himmler had told him somewhat later that Eichmann would discuss with him certain “details.” These details, Höss had claimed in his memoirs, concerned the use of gas—something Eichmann strenuously denied. And Eichmann was probably right, for all other sources contradict Höss’s story and maintain that written or oral extermination orders in the camps always went through the W.V.H.A. and were given either by its chief, Obergruppenführer Pohl, or by Brigadeführer Richard Glücks, who was Höss’s direct superior. And with the use of gas Eichmann probably had nothing to do whatever. The “details” that he went to discuss with Höss at regular intervals concerned the killing capacity of the camp—how many shipments per week they could absorb—and also, perhaps, plans for expansion.) Globocnik, when Eichmann arrived, was very obliging, and showed him around with a subordinate. They came to a road through a forest, to the right of which there was an ordinary house, where workers lived. A captain of the Order Police (perhaps Kriminal-kommissar Christian Wirth himself, who had been in charge of the technical side of the gassing of “incurably sick people” in Germany, under the auspices of the Führer Chancellery) came to greet them, led them to a group of small wooden bungalows, and, according to Eichmann, began, “in a vulgar, uneducated, harsh voice,” his explanations—“how he had everything nicely insulated, for the engine of a Russian submarine will be set to work and the gases from the engine will enter this building and the Jews will be poisoned.” Eichmann continued, “For me, too, this was monstrous. I am not so tough as to be able to endure something of this sort without any reaction. . . . If today I am shown a gaping wound, I can’t possibly look at it. I am that type of person, so that very often I was told that I couldn’t have become a doctor. I still remember how I pictured the thing to myself, and then I became physically weak, as though I had lived through some great agitation. Such things happen to everybody, and it left behind a certain inner trembling.”

Well, he had been lucky, for all he had seen this time was the preparations for the future carbon-monoxide chambers at Treblinka, one of six death camps in the East, in which several hundred thousand people were to die. In the autumn of the same year, he was sent by Müller to inspect the killing center in the Western regions of Poland that had been incorporated into the Reich. The death camp was at Chelmno (or, in German, Kulm), where, in 1944, over three hundred thousand Jews from all over Europe, who had first been “resettled” in the Lódź ghetto, were killed. Here things were already in full swing, but the method was different; instead of gas chambers, mobile gas vans were used. This is what Eichmann saw: The Jews were in a large room. They were told to strip. Then a truck arrived, stopping directly at the entrance of the room, and the naked Jews were told to enter it. The doors were closed and the truck started off. “I cannot tell [how many Jews entered],” Eichmann recalled. “I hardly looked. I could not; I could not; I had had enough. The shrieking, and . . . I was much too upset, as I told Müller when I reported to him. He did not get much profit out of my report. I then drove along after the van, and then I saw the most horrible sight I had thus far seen in my life. It [the van] was making for a long open ditch; the doors were opened, and the corpses were thrown out, as though they were still alive, so smooth were their limbs. They were hurled into the ditch, and I still have visions of how a civilian with tooth pliers made extractions. And then I was off—jumped into my car and did not open my mouth any more. Since that time, I could sit for hours beside my driver without exchanging a word with him. There I got enough. I was finished. I only remember that a physician in white overalls told me to look through a hole into the truck while they were still in it. I refused to do that. I could not. I had to disappear.”

Soon after, he was to see something that in his opinion was even more horrible. He was dispatched to Minsk, in White Russia, again by Müller, who told him, “In Minsk, they are killing Jews by shooting. I want you to report on how it is being done.” So he went, and at first it seemed as though he would be lucky, for by the time he arrived, it happened, “the affair had almost been finished,” which pleased him very much. “There were only a few young marksmen who took aim at the skulls of dead people in a large ditch,” he said. Still, he saw “a woman with her arms stretched backward, and then my knees went weak and off I went.” While driving back, he had the notion, he told the police examiner in Jerusalem, of stopping at Lwów; this seemed a good idea, because Lwów (or Lemberg) had been an Austrian city, and when he arrived there he “saw the first friendly picture after the horrors.” That, he explained, “was the railway station built in honor of the sixtieth year of Franz Josef’s reign”—a period Eichmann had always “adored,” since he had heard so many nice things about it in his parents’ home, and had also been told how the relatives of his stepmother (we are made to understand that he meant Jewish ones) had earned good money and enjoyed a comfortable social status. This sight of the railway station drove away all the horrible thoughts, and he remembered it down to its last detail—the engraved year of the anniversary, for instance. But then, right there in lovely Lwów, he made a big mistake,. He went to see the local S.S. commander, and told him, “Well, I said to him, it is horrible what is being done around here; I said young people are made into sadists. . . . How can one do that? Simply bang away at women and children? How is that possible? I said. It must not be. Our people will go mad or become insane, our own people.” The trouble was that at Lwów they were doing the same thing they had been doing in Minsk, and his host was delighted to show him the sights, although Eichmann tried politely to excuse himself. Thus, he saw another “horrible sight.” As he described the scene, “A ditch had been there, which was already filled in. And there was, gushing from the earth, a spring of blood like a fountain. Such a thing I had never seen before. I had had enough of my commission, and I went back to Berlin and reported to Gruppenführer Müller.”

This was not yet the end. Although Eichmann told Müller that he was not “tough enough” for these sights, that he had never been a soldier, had never been to the front, had never seen action, that he could not sleep and had dreams, Müller, some nine months later, sent him back to the Lublin region, where Globocnik had meanwhile finished his preparations. Eichmann said that this now became the most horrible thing he had ever seen in his life. It was as follows: When he first arrived, he could not recognize the place, with its few wooden bungalows. Instead, guided by the same man with the vulgar voice, he came to a railroad station, with the sign “Treblinka” on it, that looked exactly like an ordinary station anywhere in Germany. There were the same buildings, the same signs, the same clocks; it was a perfect imitation. “I kept myself back, as far as I could; I did not draw near to see all that. Still, I saw how a column of naked Jews filed into a large hall to be gassed. There they were killed, as I was told, by something called cyanic acid.”

The fact is that Eichmann did not see much. It is true that he repeatedly visited Auschwitz, the largest and most famous of the death camps, but Auschwitz, covering an area of about eighteen square miles, in Upper Silesia, was by no means only an extermination camp. It was a huge enterprise, with up to a hundred thousand inmates, including non-Jews and slave laborers—categories that were not subject to gassing. It was easy to avoid the killing installations, and Höss, with whom Eichmann had a very friendly relationship, spared him the gruesome sights. Eichmann never actually attended a mass execution by shooting, and he never actually watched the gassing process, or the selection of those fit for work—about twenty-five per cent of each shipment, on the average—that preceded it at Auschwitz. He saw just enough to learn how the destruction machinery worked: that there were two different killing methods, shooting and gassing; that the shooting was done by the Einsatzgruppen and the gassing at the camps, either in chambers or in mobile vans; and that in the camps elaborate precautions were taken to fool the victims right up to the end.