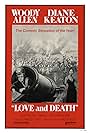

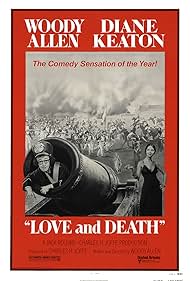

In czarist Russia, a neurotic soldier and his distant cousin formulate a plot to assassinate Napoleon.In czarist Russia, a neurotic soldier and his distant cousin formulate a plot to assassinate Napoleon.In czarist Russia, a neurotic soldier and his distant cousin formulate a plot to assassinate Napoleon.

- Awards

- 1 win & 1 nomination

Féodor Atkine

- Mikhail

- (as Feodor Atkine)

Yves Barsacq

- Rimsky

- (as Yves Barsaco)

Gérard Buhr

- Servant

- (as Gerard Buhr)

Henri Czarniak

- Ivan

- (as Henry Czarniak)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaIn an interview with 'Esquire' magazine, Woody Allen once said of the making of this movie: "When good weather was needed, it rained. When rain was needed, it was sunny. The cameraman was Belgian, his crew French. The underlings were Hungarian, the extras were Russian. I speak only English - and not really that well. Each shot was chaos. By the time my directions were translated, what should have been a battle scene ended up as a dance marathon. In scenes where Keaton and I were supposed to stroll as lovers, Budapest suffered its worst weather in twenty-five years".

- GoofsThe young Boris has blue eyes, but the adult Boris has brown eyes.

- Quotes

Sonja: To love is to suffer. To avoid suffering one must not love. But then one suffers from not loving. Therefore, to love is to suffer; not to love is to suffer; to suffer is to suffer. To be happy is to love. To be happy, then, is to suffer, but suffering makes one unhappy. Therefore, to be unhappy, one must love or love to suffer or suffer from too much happiness. I hope you're getting this down.

- Crazy creditsRussian composer Sergei Prokofiev is listed in the credits as "S. Prokofiev," just the way he would have been listed in the credits of a Russian film.

- Alternate versionsThe MGM DVD release deletes the pre-title Prokofiev overture.

- ConnectionsFeatured in V.I.P.-Schaukel: Episode #7.3 (1977)

Featured review

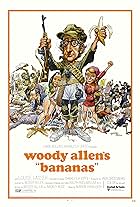

"Love and Death" is one of Woody Allen's "early, funny ones," before he made darker and more serious films, such as "Stardust Memories" (1980) where Allen's line about his own oeuvre originates. He made "Annie Hall" (1977) next, and his career would never be the same. On the other hand, being a parody of 19th-century Russian literature, "Love and Death" is full of esoteric references. The major throughline is Leo Tolstoy's "War and Peace," but there's enough Fyodor Dostoevsky here for me to have reviewed it as part of my mission to see a bunch of "Crime and Punishment" pictures after reading the book. Moreover, Allen would go on to make three movies (thus far) more heavily and singularly inspired by this particular novel: "Crimes and Misdemeanors" (1989), "Match Point" (2005) and "Irrational Man" (2015). It's interesting to compare how he went from "Love and Death," which is non-stop comedic frivolity complete with a gag being performed at every moment to "Match Point," where there are no jokes.

Indeed, "Love and Death" is not only an homage to literature, but also to early screen comics. There's even a scene where the sound goes out for some silent slapstick, and the fourth-wall-breaking absurdity of the whole thing seems to be especially indebted to the Marx Brothers. As for the Russian connection, though, there are extended mock-philosophical discussions, angst over the existence of God, somber soliloquies, multiple suitors and lovers for everyone, subplots upon subplots and periphery character galore, a lot to do with class and nationality, and... wheat, I guess. (I love that in a blog post from Alistair Ian Blyth that one of my favorite films of the 1910s, "After Death" (1915), which is based on the prose of Ivan Turgenev, is brought up to help explain the supposed importance of wheat in Russian literature.)

Some of the Dostoevsky references are obvious. Allen has a conversation in a jail cell that entirely exists of characters and titles from his stories, including some gossip about a local named "Raskolnikov" who murdered two women. Additionally, Diane Keaton's character is named "Sonja," the hooker with a heart of gold who instigates Raskolnikov's regeneration in the book. "Love and Death" offers the best character summary of Sonja, though, from her own lips: "I'm half saint, half wh-re" (IMDb censorship, you know). And, naturally, Allen plays the atheistic foil to her pious promise land. Best of all, however, is how the connection with Napoleon between "War and Peace" and "Crime and Punishment" is exploited in this film with two other words surrounding the conjunction. Sonja decides that she and Allen's Boris should kill Napoleon for the benefit of humanity, which is akin to the rationale of Raskolnikov for murdering the pawnbroker. Ironically, Napoleon was also his role model for this "extraordinary" act. Boris mixes up the roles further by comparing himself to an insect, which is what Raskolnikov said of the pawnbroker, and claiming Napoleon as a great man. Looking at the parodic adaptation this way gives one as much whiplash as Allen and Keaton's philosophical repartee. To top it off, there are two Napoleons.

There are some allusions to non-comedic films here, too. The ones to "Battleship Potemkin" (1925) and "Persona" (1966) seemed most conspicuous to me. Although "Love and Death" is a lightweight affair, and the jokes are hit and miss, it rewards those who've seen and read what it parodies. And, admittedly, Russian novels such as "Crime and Punishment" were just asking for this sort of loving pillory.

Indeed, "Love and Death" is not only an homage to literature, but also to early screen comics. There's even a scene where the sound goes out for some silent slapstick, and the fourth-wall-breaking absurdity of the whole thing seems to be especially indebted to the Marx Brothers. As for the Russian connection, though, there are extended mock-philosophical discussions, angst over the existence of God, somber soliloquies, multiple suitors and lovers for everyone, subplots upon subplots and periphery character galore, a lot to do with class and nationality, and... wheat, I guess. (I love that in a blog post from Alistair Ian Blyth that one of my favorite films of the 1910s, "After Death" (1915), which is based on the prose of Ivan Turgenev, is brought up to help explain the supposed importance of wheat in Russian literature.)

Some of the Dostoevsky references are obvious. Allen has a conversation in a jail cell that entirely exists of characters and titles from his stories, including some gossip about a local named "Raskolnikov" who murdered two women. Additionally, Diane Keaton's character is named "Sonja," the hooker with a heart of gold who instigates Raskolnikov's regeneration in the book. "Love and Death" offers the best character summary of Sonja, though, from her own lips: "I'm half saint, half wh-re" (IMDb censorship, you know). And, naturally, Allen plays the atheistic foil to her pious promise land. Best of all, however, is how the connection with Napoleon between "War and Peace" and "Crime and Punishment" is exploited in this film with two other words surrounding the conjunction. Sonja decides that she and Allen's Boris should kill Napoleon for the benefit of humanity, which is akin to the rationale of Raskolnikov for murdering the pawnbroker. Ironically, Napoleon was also his role model for this "extraordinary" act. Boris mixes up the roles further by comparing himself to an insect, which is what Raskolnikov said of the pawnbroker, and claiming Napoleon as a great man. Looking at the parodic adaptation this way gives one as much whiplash as Allen and Keaton's philosophical repartee. To top it off, there are two Napoleons.

There are some allusions to non-comedic films here, too. The ones to "Battleship Potemkin" (1925) and "Persona" (1966) seemed most conspicuous to me. Although "Love and Death" is a lightweight affair, and the jokes are hit and miss, it rewards those who've seen and read what it parodies. And, admittedly, Russian novels such as "Crime and Punishment" were just asking for this sort of loving pillory.

- Cineanalyst

- Sep 25, 2019

- Permalink

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Official site

- Language

- Also known as

- Die letzte Nacht des Boris Gruschenko

- Filming locations

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Budget

- $3,000,000 (estimated)

- Gross US & Canada

- $20,123,742

- Gross worldwide

- $20,123,742

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content