Washington race riot of 1919

| Part of Red Summer | |

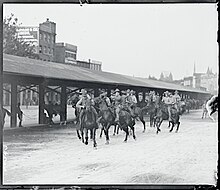

Coverage of the riots in Washington, D.C. on July 23, 1919 | |

| Date | July 19–24, 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Washington D. C., United States |

| Deaths | 15-40 [A 1] |

| Non-fatal injuries | 150 |

The Washington race riot of 1919 was civil unrest in Washington, D.C. from July 19, 1919, to July 24, 1919. Starting July 19, white men, many in the armed forces, responded to the rumored arrest of a black man for the rape of a white woman with four days of mob violence against black individuals and businesses. They rioted, randomly beat black people on the street, and pulled others off streetcars for attacks. When police refused to intervene, the black population fought back. The city closed saloons and theaters to discourage assemblies. Meanwhile, the four white-owned local papers, including the Washington Post, fanned the violence with incendiary headlines and calling in at least one instance for mobilization of a "clean-up" operation.[3]

After four days of police inaction, President Woodrow Wilson ordered 2,000 federal troops to regain control in the nation's capital.[4] But a violent summer rainstorm had more of a dampening effect. When the violence ended, 15 people had died: at least 10 white people, including two police officers;[5] and around 5 black people. Fifty people were seriously wounded and another 100 less severely wounded. It was one of the few times in 20th-century riots of whites against blacks that white fatalities outnumbered those of black people.[6] The unrest was also one of the Red Summer riots in America.

Background

[edit]Washington D.C. had evolved as one of the places in the United States where a significant number of successful African-Americans were living, with a particular concentration in the Le Droit Park area, near Howard University. This area had originally been segregated as a White-only zone, but students from Howard University had torn down the gates as part of a wider initiative to desegregate the suburb in 1888. The city as a whole was 75% composed of White Americans. To this racial mix newspaper publisher Ned McLean sought to undermine city authorities by publishing real or imagined crimes and "no crime was as salacious as a black attack on a white woman."[2] The white population were outraged by reports of black crime and during the summer of 1919 large mobs roamed streets attacking Black residents.

Charles Ralls and Elsie Stephnick

[edit]The riot initially began with a man named Charles Ralls; he was “a black man from the city’s primarily African-American Southwest quadrant”.[7] Elsie Stephnick was married to a “civilian employee of the navy”.[8] Supposedly, Ralls had assaulted Stephanick, and Ralls ended up being brought in for questioning by the police. He was released shortly afterward for lack of evidence. The preceding weeks had seen a sensationalist newspaper campaign concerning the alleged sexual crimes of a "negro fiend", which contributed to the violence of the succeeding events.[citation needed]

The riot

[edit]1st night, July 19

[edit]The race riot started on Saturday July 19 following the incident involving Charles Ralls and Elsie Stephnick. A rumor at a bar with multiple “white sailors, soldiers, and marines” began discussing the release of Ralls.[9] The rumor dispersed even farther to nearby “saloons and pool halls”.[10] and a mob soon formed that evening. The idea of the rape myth, where a black man was framed with no evidence for the rape/assault of a white woman, had been a predominant reason as to why lynching of black Americans in the United States was so widespread post-emancipation, and elements of that myth are portrayed here. The mob of White Americans, mostly consisting of veterans, formed and started towards the southwest quadrant of the city, a “predominantly black, poverty-stricken neighborhood”. They carried bats, lead pipes, and wooden boards.[11] Charles Ralls was found that Saturday evening as David Krugler wrote in his book: 1919, The Year of Racial Violence, The mob spotted Ralls walking with his wife and began beating them. The couple broke free and bolted home, shots ringing out behind them. The mob tried to break in, but Ralls’ neighbors and friends rallied to his defense — a return fusillade scattered the mob and wounded a sailor. Servicemen fired back as Black residents locked their doors and prepared to defend their homes. [p. 73].[12] The mob continued to terrorize any black American they encountered including attacks on several African Americans and also an African-American family home. Black Americans were “dragged from cars” by the veterans and beaten, and throughout all of this, there was little attention brought to the police [13] The violence continued to grow into Sunday.

2nd night, July 20

[edit]The white mob only grew more violent the next night. The group of veterans were emboldened to enact more violence considering the halfhearted effort of prevention from the police. The dean of students at Howard University, Carter Woodson, hid in the shadows in order to avoid confrontation. He recalled that others were not so lucky and stated, “They had caught a negro and deliberately held him as one would a beef for slaughter, and when they had conveniently adjusted him for lynching, they shot him. I heard him groaning in his struggle as I hurried away as fast as I could without running, expecting every moment to be lynched myself.” Beatings were also held in front of the Washington Post as well as the White House with rarely any consequences being issued for the white attackers. Because of this second night and the lack of police/military intervention, the black community opted to find protection themselves. They purchased guns and ammunition in order to ensure some source of safeguard.[14]

In response to the second night, The Washington Post ended up releasing a headline “Mobilization for Tonight” that called for all servicemen to commune on Pennsylvania Avenue around 9:00pm. Some white cavalry and marines were brought in but it was unclear whether these new troops would be “fighting the mob or joining it.”.[14]

3rd day, Monday July 21

[edit]Alarmed by the press calling for armed intervention to crush the black population, the city's black community groups spent $14,000 ($246,000 in 2024) on guns and ammunition in order to defend themselves.[2] Many black people gathered with guns they had purchased from pawn shops or military rifles black soldiers had brought home from WWI, to make a stand at around Seventh and U streets, the black district in the capital's northwest. There, sharpshooters shot at targets while perched on the roof of the Howard Theatre.[1] Many black citizens took to their cars cruising the streets and shooting up white targets. One vehicle driven by Thomas Armstead and five other passengers cruised north along 7th Street, guns blazing. Near M Street, they shot a police horse, hit the hat off a cop's head before being stopped by a group of police. Armstead and another passenger, 18-year-old Jane Gore, were shot dead, their companions escaped.[2]

4th day, July 22

[edit]

After claiming to see gunshots coming from the window, police raided the home of 17-year-old black girl, Carrie Johnson and her father. She fatally shot a white policeman, Detective Harry Wilson and claimed self-defense.[15] A bullet caught her in the thigh and her father, Ben Johnson, was shot in the shoulder. She was arrested and charged with the shooting.[2] In January 1921 a trial was finally heard, U.S. v. Carrie Johnson.[16] Her father did not testify, but the prosecutor announced in front of the jury that charges against Ben Johnson had been dropped, implying that Carrie Johnson must have committed the crime. She was convicted of manslaughter, but a separate judge accepted the self-defense argument and overturned the verdict. To avoid a second trial all charges were dropped and Carrie Johnson went free on June 21, 1921.[16]

Aftermath

[edit]The NAACP sent a telegram of protest to President Woodrow Wilson:[17][18]

...the shame put upon the country by the mobs, including United States soldiers, sailors, and marines, which have assaulted innocent and unoffending negroes in the national capital. Men in uniform have attacked negroes on the streets and pulled them from streetcars to beat them. Crowds are reported ...to have directed attacks against any passing negro....The effect of such riots in the national capital upon race antagonism will be to increase bitterness and danger of outbreaks elsewhere. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People calls upon you as President and Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces of the nation to make statement condemning mob violence and to enforce such military law as situation demands...

November Park Riot

[edit]On November 1, 1919, Albert Valentine Connors, 1014 Pennsylvania Avenue southeast, a park policeman, was assaulted by a crowd of African-Americans in an alley near Seventh and K streets southeast, shortly after noon. Connors was making an arrest when he was mobbed by a large crowd. After being stabbed and beaten he was able to call for more police and the crowd dispersed.[19]

Potential Causes

[edit]At the time of the Washington Race Riot, Walter White was the assistant executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). While in this leadership position, he outlined eight specific causes that were of great significance in regard to the Chicago Race Riot. This event occurred just about a week after the tragedy in Washington, on July 27, 1919. White’s understandings can be applied to the former event due to their extreme similarities in time and events. These causes include: “race prejudice, economic competition, political corruption and exploitation of negro voters, police inefficiency, newspaper lies about negro crime, unpunished crimes against negroes, housing, and the reaction of whites and negroes from war”.[20] He lists them in this order according to their importance in regard to the event.

Race prejudice was apparent throughout the United States, not just in Washington. While tensions were always high between whites and blacks during American history, these issues began to grow during the Jim Crow Era. The Jim Crow Laws allowed white people to make rules that allowed segregation despite the freedom of black citizens in the U.S. An example of a Jim Crow Law given by Ferris State University about burial is, “The officer in charge shall not bury, or allow to be buried, any colored persons upon ground set apart or used for the burial of white persons (Georgia)”.[21] In addition to the Jim Crow Era, tensions began to rise because of the migration of Southern blacks to the North. Walter White also describes this change when writing, “Southern whites have also come into the North, many of them to Chicago, drawn by the same economic advantages that attracted the colored workman. The exact figure is unknown, but it is estimated by men who should know that fully 20,000 of them are in Chicago. These have spread the virus of race hatred and evidence of it can be seen in Chicago on every hand”.[22] In this quote, Chicago and Washington are interchangeable. Because these events happened in such a small time frame, the societal challenges and issues of both cities were extremely similar. These racial tensions continue to build up. The Washington Race Riot was a clear example of what occurred when agitation built up and exploded"

Economic competition connects to the previous cause. Due to the influx of black southerners to northern towns (the Great Migration), many different economic and social changes were occurring. One example is that companies could hire black workers and pay them less than their white counterparts, which many opted to do. This unequal pay was unfair but not uncommon. Richard B. Freeman, a professor at Harvard, describes this situation in the 1960s in the quote, “blacks had markedly lower incomes than whites, on average and within comparable occupational or educational groups”.[23] This situation also caused lots of race tension because white workers were losing their jobs to newly residential black workers. Violence levels due to race-related motives were already high. The increasing competition of the job market increased the severity and number of these events. Barbra Foley writes about the negative conditions in the North for black citizens. She writes, “Robert Russa Moton, counseled African American troops in France to go back to the rural South after the war, warning them of the dangers and poverty-stricken conditions they would face in such northern centers as New York",[24] advising black troops to continue to live in the South after the war. While the conditions in the Northern United States were far from perfect, there were far more opportunities.

Race prejudice, economic competition, political corruption and exploitation of negro voters, police inefficiency, newspaper lies about black crime, unpunished crimes against African Americans, housing, and the divergent experiences of whites and blacks during WWI were important causes of this event. All of these factors, most importantly race prejudice and economic competition, prove themselves as crucial in the build-up of the Washington Race Riot. These events were occurring in Washington as well as around all of the United States. White people’s anger at blacks due to the color of their skin as well as the changes that were occurring in the nation lead to their many outbursts of violence. These detrimental activities usually included lynchings, which the Call describes in an article written in the summer of 1919. It states, “Not until our black brothers are free to walk the streets of American cities unmolested, not until they have free access to all callings and professions, not until they are free to organize politically in the South and to vote without being clubbed and shot, will this country be anything else than an autocracy to them”.[25] Events like the clubbings and shootings the news source describe the atmosphere of the racist United States as seen during this time. These events eventually escalated to large-scale attacks such as the Race Riot of 1919 in Washington.

See also

[edit]- 1968 Washington, D.C. riots

- 1991 Washington, D.C. riot

- First Red Scare

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- King assassination riots

- 1919 Norfolk race riot

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- False accusations of rape as justification for lynchings

Further reading

[edit]- McWhirter, Cameron (2011). Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9781429972932.

- Spears, Charles Alan (1999). This Nation's Gratitude: The Washington, D.C. Race Riot of 1919. M.A. thesis, Howard University.

Annotations

[edit]- ^ Official reports claim a death toll of 15 (10 whites and 5 blacks).[1] Author Michael Schaffer claims that "the violence claimed 30 to 40 lives ... those estimates make the riots almost three times as deadly as the far more famous upheavals of April 1968."[2]

Bibliography

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b Lewis 2015

- ^ a b c d e Schaffer 1998

- ^ Perl 1999, p. A1

- ^ "Washington, D.C. Race Riot (1919) – The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. April 2, 2016.

- ^ ODMP Memorials Wilson and Halbfinger

- ^ Ackerman 2011

- ^ "Red Summer Race Riot in Washington, 1919". April 18, 2017.

- ^ "July 19, 1919: White Mobs in Uniform Attack African Americans — Who Fight Back — in Washington, D.C."

- ^ "July 19, 1919: White Mobs in Uniform Attack African Americans — Who Fight Back — in Washington, D.C."

- ^ "July 19, 1919: White Mobs in Uniform Attack African Americans — Who Fight Back — in Washington, D.C."

- ^ "Washington, D.C. Race Riot (1919) •". April 2, 2016.

- ^ "July 19, 1919: White Mobs in Uniform Attack African Americans — Who Fight Back — in Washington, D.C."

- ^ "Washington, D.C. Race Riot (1919) •". April 2, 2016.

- ^ a b Brockell 2019.

- ^ Sauer 2019.

- ^ a b Morley 2019.

- ^ New York Times: "Protest Sent to Wilson," July 22, 1919. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ GlobalSecurity.org 2019

- ^ "Policeman Beaten by Gang". Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers site. The Washington Herald. November 2, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ ""Chicago and Its Eight Reasons": Walter White Considers the Causes of the 1919 Chicago Race Riot".

- ^ "What was Jim Crow - Jim Crow Museum".

- ^ ""Chicago and Its Eight Reasons": Walter White Considers the Causes of the 1919 Chicago Race Riot".

- ^ Freeman 1973, pp. 67–131.

- ^ Foley, Barbara (2003). "The New Negro and the Left". Spectres of 1919. University of Illinois Press. pp. 1–69. ISBN 9780252075858. JSTOR 10.5406/j.ctt2ttdv3.4.

- ^ Foley, Barbara (2003). "The New Negro and the Left". Spectres of 1919. University of Illinois Press. pp. 1–69. ISBN 9780252075858. JSTOR 10.5406/j.ctt2ttdv3.4.

References

- Ackerman, Kenneth (2011). Young J. Edgar: Hoover and the Red Scare, 1919–1920. Viral History Press LLC. ISBN 9781619450011. - Total pages: 467

- Brockell, Gillian (July 15, 2019). "The deadly race riot 'aided and abetted' by The Washington Post a century ago". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- Freeman, Richard B. (1973). "Changes in the Labor Market for Black Americans, 1948-72" (PDF). University of Chicago and Harvard University. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- GlobalSecurity.org (2019). "Race Riots of 1919". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- Lewis, Tom (November 2, 2015). "How Woodrow Wilson Stoked the First Urban Race Riot". Politico. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- Morley, Jefferson (July 17, 2019). "The D.C. Race War of 1919: And the forgotten story of one African American girl accused of murdering a police officer". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. OCLC 2269358. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- Sauer, Patrick (July 17, 2019). "One Hundred Years Ago, a Four-Day Race Riot Engulfed Washington, D.C." Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Perl, Peter (March 1, 1999). "Race Riot of 1919 Gave Glimpse of Future Struggles". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- Rucker, Walter C.; Upton, James N. (2007). Encyclopedia of American Race Riots, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313333026. - Total pages: 930

- Schaffer, Michael (April 3, 1998). "Lost Riot: Thirty years ago this week, Washington burned. Seventy-nine years ago this summer, the city bled. Why we shouldn't forget the riots of 1919". Washington City Paper. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- The Washington Herald (2019). "Policeman Beaten By Gang of Negroes". The Washington Herald. ISSN 1941-0662. OCLC 9470809. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- African-American history of Washington, D.C.

- 1919 in Washington, D.C.

- Riots and civil disorder in Washington, D.C.

- 1919 riots in the United States

- July 1919 events

- White American riots in the United States

- Red Summer

- White American culture in Washington, D.C.

- Anti-black racism in Washington, D.C.

- Presidency of Woodrow Wilson