The Getaway (1972 film)

| The Getaway | |

|---|---|

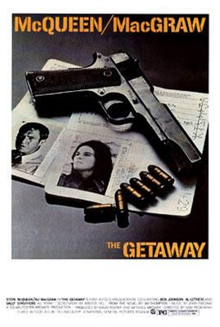

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sam Peckinpah |

| Screenplay by | Walter Hill |

| Based on | The Getaway 1958 novel by Jim Thompson |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Lucien Ballard |

| Edited by | Robert L. Wolfe |

| Music by | Quincy Jones |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | National General Pictures[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 122 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.3 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $36.7 million (US)[4] |

The Getaway is a 1972 American action thriller film based on the 1958 novel by Jim Thompson. The film was directed by Sam Peckinpah, written by Walter Hill, and stars Steve McQueen, Ali MacGraw, Ben Johnson, Al Lettieri, and Sally Struthers. The plot follows imprisoned mastermind robber Carter "Doc" McCoy, whose wife Carol conspires for his release on the condition they rob a bank in Texas. A double-cross follows the crime, and the McCoys are forced to flee for Mexico with the police and criminals in hot pursuit.

Peter Bogdanovich, whose The Last Picture Show impressed McQueen and producer David Foster, was originally hired as the director of The Getaway. Thompson came on board to write the screenplay, but creative differences ensued between him and McQueen, and Thompson was subsequently fired, along with Bogdanovich. Writing and directing duties eventually went to Hill and Peckinpah, respectively. Principal photography commenced February 7, 1972, on location in Texas. The film reunited McQueen and Peckinpah, who had worked together on the relatively unprofitable Junior Bonner, released the same year.

The Getaway premiered December 13, 1972.[citation needed] Despite the negative reviews it received upon release, numerous retrospective critics give the film good reviews. A box-office hit earning over $36 million, it was the eighth highest-grossing film of 1972, and one of the most financially successful productions of Peckinpah's and McQueen's careers. A film remake of the same name starring Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger was released in 1994.

Plot

[edit]Four years into his ten-year sentence for armed robbery, Carter "Doc" McCoy is denied parole from a Texas prison. When his wife Carol visits him, he tells her to do whatever is necessary to make a deal to free him with Jack Beynon, a parole board member and corrupt businessman in San Antonio. Beynon facilitates Doc's parole on the condition that he plan and take part in a bank robbery with two henchmen, Rudy Butler and Frank Jackson. The robbery initially goes as planned, until Frank kills a security guard. Rudy then kills Frank in their car. At the designated meeting place, an old farmyard, Rudy tries to shoot Doc, but Doc anticipates Rudy's double-cross and shoots Rudy several times. Doc and Carol take the $500,000 (equivalent to $3.64 million in 2023) and flee. Rudy, having secretly worn a bulletproof vest, is only wounded.

When Doc meets with Beynon at his ranch, Carol sneaks in to kill Doc, per a double-cross Beynon arranged with her. However, Carol draws her gun on Beynon and kills him instead. Doc, having just been taunted by Beynon before Carol shot him, realizes that Carol had sex with Beynon to secure his parole. He angrily gathers the money and, after a bitter quarrel, the couple goes to the border at El Paso.

Rudy manages to collect himself and drive to the home of rural veterinarian Harold Clinton, who treats his injuries. Rudy kidnaps the doctor and his wife Fran to pursue Doc and Carol. Beynon's brother, Cully, and his team also track down the McCoys. At a train station, a con man swaps locker keys with Carol and steals their bag of money. Doc follows him onto a train and forcibly takes it back, although the thief has already pocketed a packet of the money. The injured thief and a train passenger—a boy Doc had rebuked for squirting him with a water gun—are taken to the police station, where they identify Doc's mug shot.

Carol buys a car, and they drive to an electronics store. As Doc buys a portable radio, the other radios and the televisions start broadcasting the news of the earlier incidents in which they were involved. Doc leaves immediately, but the proprietor gets a glimpse of his picture on TV and calls the police. Doc steals a shotgun from a neighboring sporting goods store, and shoots up the arriving police car to prevent the officers from chasing them.

The mutual attraction between Rudy and Fran, the veterinarian's wife, leads to them having consensual sex on two occasions in front of her husband, who is tied up in a chair at a motel. Humiliated, the vet hangs himself in the bathroom. Rudy and Fran move on, barely acknowledging the suicide. They check into El Paso's Laughlin Hotel, used by criminals as a safe house, as Rudy knows that the McCoys will be heading to the same place. When Doc and Carol check in, they ask for food to be delivered, but the manager, Laughlin, says he is working alone and cannot leave the desk. Doc realizes Laughlin sent his family away because something nasty is about to happen. He urges Carol to dress quickly so they can escape. An armed Rudy comes to their door while Fran poses as a delivery girl. Peering from an adjacent doorway, Doc is surprised to see Rudy alive. He sneaks up behind Rudy, knocks him out, and does the same to Fran.

Cully and his thugs arrive as the McCoys try to leave the hotel. A violent gunfight ensues in the halls, stairwell and elevator, and all but one of Cully's men are killed; Doc allows him to run away safely. Rudy comes to, follows Doc and Carol outside onto a fire escape, and shoots at them. Doc returns fire and kills him. With the police on the way, the couple hijack a pickup truck and force the driver, a cooperative old cowboy, to take them to Mexico. After crossing the border, Doc and Carol pay the cowboy $30,000 (equivalent to $219,000 in 2023) for his old truck. Overjoyed, the cowboy heads back to El Paso on foot, while the couple continues into Mexico, having gotten away with their crimes and the remainder of the money.

Cast

[edit]- Steve McQueen as Doc McCoy

- Ali MacGraw as Carol McCoy

- Ben Johnson as Jack Beynon

- Al Lettieri as Rudy Butler

- Sally Struthers as Fran Clinton

- Slim Pickens as the cowboy

- Richard Bright as the thief

- Jack Dodson as Harold Clinton

- Dub Taylor as Laughlin

- Bo Hopkins as Frank Jackson

- Roy Jenson as Cully

- John Bryson as the accountant

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Steve McQueen had been encouraging his publicist David Foster to enter the film industry as a producer for years.[5] His first attempt was Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, with McQueen starring alongside Paul Newman, but 20th Century Fox, particularly its president, Richard D. Zanuck, did not want Foster as part of the deal. Rather, Zanuck hired producer Paul Monash, since he was the studio's profit maker, resulting in McQueen's departure from the project.[6] While McQueen was making Le Mans, Foster acquired the rights to Jim Thompson's crime novel The Getaway. Foster sent McQueen a copy of the book, urging him to do it. The actor was looking for a "good bad-guy" role, and saw these qualities in the novel's protagonist, Doc McCoy.[6]

Foster looked for a director, and Peter Bogdanovich came to his attention.[7] Bogdanovich's agent, Jeff Berg, set up a special screening of his client's soon-to-be released The Last Picture Show for Foster, with McQueen in attendance. They loved it and met with the director, and a deal was reached.[7] However, Warner Bros. approached Bogdanovich with an offer to direct What's Up, Doc? starring Barbra Streisand, with the stipulation that he had to start right away. The director wanted to do both, but the studio refused. When McQueen heard this, he became upset and told Bogdanovich that he was going to get someone else to direct The Getaway.[8]

McQueen had recently worked with director Sam Peckinpah on Junior Bonner and enjoyed the experience,[8] but the film proved to be unsuccessful. He said, "Out of all my movies, Junior Bonner did not make one cent. In fact, it lost money."[5] McQueen recommended that Foster approach Peckinpah. Like McQueen, Peckinpah was in need of a box-office hit and immediately accepted. The filmmaker had read the novel when it was originally published, and had talked to Thompson about making a film adaptation when he was starting out as a director.[8]

At the time, Peckinpah wanted to make Emperor of the North Pole, a story set during the Great Depression about a brakeman obsessed with keeping homeless people off his train.[9] The film's producer made a deal with Paramount Pictures' production chief Robert Evans, allowing Peckinpah to do his personal project if he first directed The Getaway. The director was soon dismissed from Emperor and told that Paramount was not making The Getaway.[9]

A conflict arose with Paramount over the film's budget.[10] Foster had thirty days to set up a new deal with another studio, or Paramount would own the exclusive rights. He was inundated with offers, and accepted one from First Artists because McQueen would receive no upfront salary, but just ten percent of the gross receipts from the first dollars earned on the film. This would become very profitable, but only if the film was a box-office hit, which it was.[10]

Writing

[edit]Jim Thompson was hired by Foster and McQueen to adapt his novel. He worked on the screenplay for four months, changing some of the scenes and episodes in his novel.[11] Thompson's script included the borderline surrealistic ending from his novel, featuring El Rey, an imaginary Mexican town filled with criminals. McQueen objected to the depressing ending, and Thompson was replaced by screenwriter Walter Hill.[11] Hill had been recommended by Polly Platt, Bogdanovich's wife, who was then still attached to direct. Platt had been impressed by Hill's work on Hickey & Boggs. Hill said Bogdanovich wanted to turn the material into a more Hitchcock-type thriller, but he had written only the first twenty-five pages when McQueen fired the director. Hill finished the script in six weeks, then Peckinpah came on board.[12]

Peckinpah read Hill's draft, and the screenwriter remembered that he made few changes: "We made it non-period and added a little more action".[13] On Thompson's novel, Hill said:

I didn't think you could do Thompson's novel. I thought you had to make it more of a genre film. Thompson's novel is strange and paranoid, has this fabulous ending in an imaginary city in Mexico, criminals who bought their freedom by living in this kingdom. It's a strange book. It's written in the fifties, takes place in the fifties, but it is really a thirties story. I did not believe that if you faithfully adapted the novel the movie would get made, or that McQueen would get the part. There was a brutal nature to Doc McCoy that was in the book that I thought you weren't going to be able to go that far and get the movie made. I found myself in this strange position, trying to make it less violent.[14]

Casting

[edit]When Bogdanovich was to direct, he intended to cast Cybill Shepherd, his then girlfriend, in the role of Carol. As soon as Peckinpah came on to direct, he wanted to cast Stella Stevens, with whom he had worked on The Ballad of Cable Hogue, with Angie Dickinson and Dyan Cannon as possible alternatives. Foster suggested Ali MacGraw, a much in-demand actress after the commercial success of Love Story.[13] She was married to Robert Evans, who wanted her to avoid being typecast in preppy roles, and set up a meeting for her with Foster, McQueen and Peckinpah about the film.[15] According to Foster, she was scared of McQueen and Peckinpah because they had reputations as "wild, two-fisted, beer guzzlers".[15] McQueen and MacGraw experienced a strong instant attraction. "He was recently separated and free," she said, "and I was scared of my overwhelming attraction to him."[15] MacGraw was paid $300,000 plus German distribution rights.[16]

Peckinpah originally wanted actor Jack Palance to play the role of Rudy Butler, but could not afford his salary.[17] Impressed by his performance in The Panic in Needle Park, Hill recommended Richard Bright.[18] Bright had worked with McQueen fourteen years before, but he did not have the threatening physique that McQueen pictured for Butler, especially because the two men were the same height. Due to his friendship with Bright, Peckinpah cast him as the con man.[18] Al Lettieri was brought to Peckinpah's attention for the role of Butler by producer Albert S. Ruddy, who was working with the actor on The Godfather (1972). Like Peckinpah, Lettieri was a heavy drinker, which caused problems while filming due to his unpredictable behavior.[17]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography of The Getaway began in Huntsville, Texas, February 7, 1972. Peckinpah shot the opening prison scenes at the Huntsville Penitentiary, with McQueen surrounded by actual convicts.[19] Other shooting locations included the Texas towns San Marcos,[20] San Antonio [21] and El Paso.[22] The climactic scenes at El Paso's Laughlin Hotel — demolished in 2013 (along with City Hall) to make way for Southwest University Park — include the curved framework of the Abraham Chavez Theatre, visible under-construction nearby,[23] and the construction site, including the adjacent El Paso Civic Center.

McQueen and MacGraw began an affair during production.[24] She would eventually leave her husband, Evans, and become McQueen's second wife. Foster was worried their relationship could have a potentially negative impact on the film by causing a scandal.[25] MacGraw got her start as a model, and her inexperience as an actress was evident on the set as she struggled with the role.[26] According to Foster, the actress and Peckinpah got along well, but she was not happy with her performance. She would say, "After we had completed The Getaway and I looked at what I had done in it, I hated my own performance. I liked the picture, but I despised my own work."[22]

Peckinpah's intake of alcohol increased dramatically when making The Getaway, and he was fond of saying, "I can't direct when I'm sober."[27] He and McQueen got into occasional heated arguments during filming. The director recalled one such incident on the first day of rehearsal in San Marcos: "Steve and I had been discussing some point on which we disagreed, so he picked up this bottle of champagne and threw it at me. I saw it coming and ducked. And Steve just laughed."[28] McQueen had a knack with props, especially the weapons, he used in the film. Hill remembered, "You can see Steve's military training in his films. He was so brisk and confident in the way he handled the guns."[29] It was McQueen's idea to have his character shoot and blow up a squad car in the scene where Doc holds two police officers at gunpoint.[29]

Under his contract with First Artists, McQueen had final cut privileges on The Getaway. When Peckinpah found out, he was upset. Richard Bright said McQueen chose takes that "made him look good", and Peckinpah felt that the actor had played it safe. Said Peckinpah: "He chose all these Playboy shots of himself. He's playing it safe with these pretty-boy shots."[22]

Music

[edit]Peckinpah's longtime composer and collaborator Jerry Fielding was commissioned to score The Getaway. He had worked previously with the director on Noon Wine, The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs and Junior Bonner. After the film's second preview screening, McQueen was unhappy with the music, and used his clout to hire Quincy Jones to rescore the film.[22] Jones' music had a jazzier edge, and featured harmonica solos by Toots Thielemans and vocals by Don Elliott, both of whom had been his associates.[30] Peckinpah was unhappy with this action and took out a full-page ad in Daily Variety November 17, 1972, which included a letter he had written to Fielding thanking him for his work. Fielding would work with Peckinpah on two more films, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia and The Killer Elite.[31] Jones was nominated for a Golden Globe award for his original score.[32]

Release

[edit]Theatrical run and box office

[edit]There were two preview screenings for The Getaway: a lackluster one in San Francisco and an enthusiastic one in San Jose, California.[33] The film opened in Los Angeles on December 19, 1972. From 17 US cities tracked by Variety, it grossed $638,166 from 35 theaters in its opening week, finishing third at the box office behind The Poseidon Adventure and Across 110th Street.[34] In its third week of release, the film moved to number one at the US box office with an estimated gross of $874,800 from thirty-nine locations tracked.[3][35] The film had grossed $18,943,592 by the end of 1973,[36] and went on to become the eighth highest-grossing film of the year. Its rentals in the United States and Canada for that year were $17,500,000.[37] On a production budget of $3,352,254,[2][3] the film grossed $36,734,619 in the U.S. and Canada alone.[4]

Walter Hill later recalled:

I thought of the films I wrote, I thought it was far and away the best one, and most interesting. I thought Sam did a few things while shooting that were terrific. (...) It was not reviewed very well, but a huge hit. Biggest hit Sam ever had. (...) He would always say we did this one for the money which is one of those kind of half truths. (...) He was well paid and the movie made a lot of money and the fact it was about the only film where his points meant anything; he took a fair amount of money out, too. After all the disappointment and heartbreak of all these films he had never gotten any reward or been well paid, meant a lot to him.[14]

Home media

[edit]Warner Home Video released a two-disc DVD version of The Getaway November 19, 1997, presented in both widescreen and pan and scan. Warner released the film again on DVD as part of The Essential Steve McQueen Collection seven-disc box set May 31, 2005, followed by an HD DVD and a Blu-ray version February 27, 2007.[38]

Special features include audio commentary by Peckinpah's biographers, and documentarians Nick Redman, Garner Simmons, David Weddle and Paul Seydor, and a 12-minute "virtual" commentary by Peckinpah, McQueen and MacGraw. There is also a featurette entitled Main Title 1M1 Jerry Fielding, Sam Peckinpah & The Getaway, which includes interviews with composer Jerry Fielding's wife and two daughters, and Peckinpah's assistant.[39]

Critical reception

[edit]Initial reaction to The Getaway was negative.[40] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "aimless".[41]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times complained that the story was contrived, calling it "a big, glossy, impersonal mechanical toy", and rated it 2 of 4 stars.[42]

The New Yorker's Pauline Kael said the onscreen relationship between McQueen and MacGraw leaves much to be desired. In hindsight, Kael referred to MacGraw as a much worse actress than Candice Bergen.[40]

Jay Cocks of Time felt Peckinpah "was pushing his privileges too far", but complimented his film as "a work of a competent craftsman".

The New York Daily News' Kathleen Carroll denounced the film for being "too violent and vulgar".[40]

John Simon called The Getaway "a sourly disappointing, ugly, and unbelievable film".[43]

Conversely, the Chicago Tribune's Gene Siskel said The Getaway "play[ed] like a 1970s Bonnie and Clyde", giving it 3½ of 4 stars.[44] Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic wrote, "McGraw is a zero, so she makes us question her all the time. Outside of that (immense) flaw in casting, the picture is smashing."[45]

Modern criticism has been more appreciative. Dennis Schwartz of Ozus' World Movie Reviews gave it a B-grade rating, praising most of the film's action sequences, and calling it "a gripping thriller (...) filmed in Peckinpah's excessive action-packed violent and amoral style".[46]

Newell Todd of CHUD.com scored it 7 out of 10, considering it "an entertaining film that is only made better with some McQueen action".[47]

Casey Broadwater of blu-ray.com described it as "an effective thriller that plays with and against some of [Peckinpah's] well-noted stylistic trademarks, ... a well-constructed, lovers on the run-style heist flick".[48]

Writing for Cinema Crazed, Felix Vasquez lauded most action scenes, and remarked, "The Getaway is a top notch crime thriller with a fantastic turn by McQueen and it's still the best action movie I've ever seen."[49]

Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 83% based on 23 reviews from critics, with an average rating of 6.9/10. The website's consensus reads, "The Getaway sees Sam Peckinpah and Steve McQueen, the kings of violence and cool, working at full throttle."[50] Rotten Tomatoes also ranks the film at number 47 on its "75 Best Heist Movies of All Time" list.[51]

In 2010, The Playlist included The Getaway on its list of the "25 All-Time Favorite Heist Movies", describing it as "a solid, straight-ahead action flick that's always fun to wander into the middle of on late night TV".[52]

Remake

[edit]A remake of the film, directed by Roger Donaldson and co-written by Walter Hill, was released February 11, 1994. It stars Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger, with Michael Madsen, James Woods, David Morse and Jennifer Tilly.[53] The film received negative reviews upon its release, with critics calling it a clichéd and uninspired retread of the Peckinpah film.[54] In 2008, Baldwin referred to it as a "bomb".[55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e The Getaway at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ a b Eliot 2011, p. 222.

- ^ a b c Weddle 1994, p. 310.

- ^ a b "The Getaway (1972)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ a b Terrill 1993, p. 219.

- ^ a b Terrill 1993, p. 220.

- ^ a b Terrill 1993, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Terrill 1993, p. 222.

- ^ a b Simmons 1982, p. 154.

- ^ a b Terrill 1993, p. 226.

- ^ a b Geffner, David (December 2, 1996). "Jim Thompson's Lost Hollywood Years". MovieMaker. MovieMaker Media, LLC. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ McGilligan, Patrick (June 2004). "Walter Hill: Last Man Standing" (PDF). Film International. Intellect Ltd. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ a b Terrill 1993, p. 224.

- ^ a b Markowitz, Robert. "Visual History with Walter Hill (Chapter 3)". Directors Guild of America. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c Terrill 1993, p. 225.

- ^ Murphy, A.D. (October 11, 1972). "Hoffman Tie With First Artists Prod. Unveils Four Stars' Internal Setup; Ali McGraw Got 300G For 'Getaway'". Variety. p. 3.

- ^ a b Terrill 1993, p. 235.

- ^ a b Terrill 1993, p. 234.

- ^ Terrill 1993, p. 227.

- ^ Terrill 1993, p. 232.

- ^ Terrill 1993, p. 239.

- ^ a b c d Terrill 1993, p. 241.

- ^ "Hotel Laughlin, El Paso, Texas". digie.org. Archived from the original on 2023-06-10. Retrieved 2023-10-20.

The Laughlin Hotel is part of the Old San Francisco District. … A scene in "The Getaway" starring Steve Mc Queen was filmed in the Laughlin. It was located where the Chihuhahua´s stadium is now. At the time of filming, the convention center was under construction… and the frame work for the Abraham Chavez Theater can be seen…

- ^ Terrill 1993, pp. 228.

- ^ Terrill 1993, p. 230.

- ^ Terrill 1993, p. 240.

- ^ Weddle 1994, pp. 444–450.

- ^ Terrill 1993, p. 237.

- ^ a b Terrill 1993, p. 238.

- ^ Burlingame, Jon (March 1, 2013). "Q's cues, and all that jazz". Variety. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ Simmons 1982, pp. 165–167.

- ^ "The 30th Annual Golden Globe Awards (1972)". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ Terrill 1993, p. 245.

- ^ "50 Top-Grossing Films". Variety. January 10, 1973. p. 9.

- ^ "50 Top-Grossing Films". Variety. January 17, 1973. p. 11.

- ^ Sandford 2003, p. 301.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973", Variety, January 9, 1974 p. 19

- ^ "The Getaway (1972): Releases". AllMovie. All Media Network. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ Bracke, Peter (February 27, 2007). "The Getaway (1972)". High Def Digest. Internet Brands, Inc. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c Terrill 1993, p. 246.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (December 20, 1972). "Thief and Wife in Getaway". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1972). "The Getaway Movie Review & Film Summary (1972)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Simon, John (1982). Reverse Angle: A Decade of American Film. Crown Publishers Inc. p. 100. ISBN 9780517544716.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 22, 1972). "Escapism is in season over on State Street". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 1.

- ^ Kauffmann, Stanley (1974). Living Images Film Comment and Criticism. Harper & Row Publishers. p. 167.

- ^ Schwartz, Dennis (April 4, 2013). "A gripping thriller". Ozus' World Movie Reviews. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Todd, Newell (June 19, 2005). "DVD Review: The Getaway (DE)". CHUD.com. Nick Nunziata. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ Broadwater, Casey (July 23, 2009). "The Getaway Blu-ray – Review". Blu-ray.com. Internet Brands, Inc. Archived from the original on April 25, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Vasquez, Felix (August 22, 2013). "The Getaway (1972)". Cinema Crazed. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ "The Getaway (1972)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on April 19, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Best Heist Movies of All Time". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media.

- ^ The Playlist Staff (September 17, 2010). "25 All-Time Favorite Heist Movies". IndieWire. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on January 1, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (February 9, 1994). "Review: The Getaway". Variety. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^

- Ebert, Roger (February 11, 1994). "The Getaway Movie Review and Film Summary (1994)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- James, Caryn (February 11, 1994). "Reviews/Film; In the Tire Tracks Of Another Sultry Pair". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- Gleiberman, Owen (February 11, 1994). "The Getaway (Movie - 1994)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ Parker, Ian (September 8, 2008). "Why me?". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

In '93, I did the remake of The Getaway, with my wife [Basinger]. That was a bomb.

Bibliography

[edit]- Eliot, Marc (2011). Steve McQueen: A Biography. New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-84513-744-1.

- Sandford, Christopher (2003). McQueen: The Biography. New York: Taylor Trade Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87833-307-3.

- Simmons, Garner (1982). Peckinpah, A Portrait in Montage. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-87910-273-9.

- Terrill, Marshall (1993). Steve McQueen: Portrait of an American Rebel. Plexus. ISBN 978-1-55611-414-4.

- Weddle, David (1994). If They Move...Kill 'Em! The Life and Times of Sam Peckinpah. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3776-0.

External links

[edit]- The Getaway at IMDb

- The Getaway at the TCM Movie Database

- The Getaway at AllMovie

- The Getaway at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- 1972 films

- 1970s action thriller films

- 1970s crime thriller films

- 1970s heist films

- Films about adultery in the United States

- American action thriller films

- American chase films

- American crime thriller films

- American heist films

- Films scored by Quincy Jones

- Films about bank robbery

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on crime novels

- Films based on Jim Thompson novels

- Films directed by Sam Peckinpah

- Films set in Houston

- Films set in Texas

- Films shot in El Paso, Texas

- Films shot in New Braunfels, Texas

- Films shot in San Antonio

- First Artists films

- American neo-noir films

- Films with screenplays by Walter Hill

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s American films

- English-language action thriller films

- English-language crime thriller films