Servitude (Roman law)

In Roman law, the praedial servitude or property easement (in Latin: iura praedorium or servitutes praediorum), or simply servitude (servitutes), consists of a real right the owners of neighboring lands can establish voluntarily, in order that a property called servient lends to other called dominant the permanent advantage of a limited use. As use relations, servitudes are fundamentally solidary and indivisible rights, the latter being what causes the servitude to remain intact despite the fact that any property involved may be divided. Furthermore, there is no possibility of acquisition or partial extinction.[1][2]

As a type of concurrence of rights, the servitude produces a limitation of the ownership of the servient estate. It is the property that suffers the encumbrance, but the owner is at no time personally obliged; this is why the servitude cannot consist in a doing, but rather in a limitation. Although on the part of the servient estate the service may involve a tolerance, from the dominant party's point of view it may consist of a lawful interference (immissio) on the servient estate (affirmative servitude), or of a right to prevent (ius prohibendi) certain acts on the servient estate (negative servitude). When the service provided can be recognized by a sign, such as a window or a canal, the easement is called apparent, while in the opposite case, that is, when there is no such sign, the easement is called not apparent.[3]

In principle, intrusions into another's real estate are not legally permitted, so the owner has the possibility to prevent them (ius prohibendi), and in case of persistence, he can resort to interdicta uti possidetis and quod vi aut clam or to the corresponding negatory actions. For his part, the owner may do whatever he sees fit on his property as long as his actions do not entail an interference with the neighboring estate. Only by means of the constitution of an servitude can an intromission be made lawful, or one of the acts of the owner on the property become unlawful.[4]

Types of servitudes

[edit]Property servitudes are typified on the basis of their specific content. Although there is no reason to believe that jurisprudence could not recognize more types of easements than those stipulated in its casuistic works, there is an established series of these types, which the scholastic authors grouped into rustic and urban depending on whether they referred to being able to pass or bring water through the neighboring property, among other advantages of a markedly agricultural nature, or whether they dealt with the amenities of a building that is imposed on the neighbor. It was mainly the early classical Roman jurisprudence that dealt with the casuistry of easements, a position that led to a series of criticisms from non-lawyers, such as Cicero, who considered such questions as ridiculous.[5]

Main rustic property servitudes

[edit]

The most important rustic property servitudes (servitutes praediorum rusticorum) are those of passage on foot or horseback (iter), the passage of livestock (actus) or way for carts (via). Also relevant are those of surface water conduction (aquae ductus), water extraction (aquae haustus), which according to jurisprudential interpretation entails access to the well or spring (iter ad hauriendum) and the right to pour water on neighboring property (aquae immissio).[6]

Main urban property servitudes

[edit]The most important urban property servitudes (servitutes praediorum urbanorum) are those of light and views, either in its variant of being able to open windows (ius luminum), prevent the neighbor to raise an existing building (ius altius non tollendi) or the right of views (ius ne prospectui vel luminibus officiatur). Others are the sanitary sewer easements (also called "of waters". Sewer), support of a beam (ius tigni immittendi) or burden of an overconstruction (ius oneris ferendi). There are also those of overhangs, to let rainwater fall from the roof (ius stillicidii) or through a gutter (ius fluminis, both are exercised by the actio aquae pluviae arcendae), and that of projecting balconies or terraces over a neighboring property (ius proiiciendi protegendive).[6]

Procedural defense

[edit]The owner of the dominant estate had a vindicatio servitutis (this may also appear as actio confessoria in post-classical writings) that could be exercised against the owner or possessor of the servient estate, or against any other person who did not allow the exercise of the servitude. The vindicatio servitutis, which was characterized by its similarity to the vindicatory action, contained an arbitrary clause that made acquittal easier in exchange for a bond not to continue to disturb (de non amplius turbando). This same caution was demanded by the praetor from the person who did not defend himself against the vindicatio servitutis with the intention of not preventing the use of the servitude until the denial action was exercised and the servitude was declared non-existent. At the same time, from the person who did not accept the denial action, a bond was required not to exercise the denied servitude as long as a favorable judgment was not issued in his favor. In other situations, the use of servitudes could be defended by means of special injunctions. However, the interdict uti possidetis was not applicable, since the servitude consisted in a use and not in a possession.[7][8]

The owner of the dominant property had a restitutory injunction against works started on the neighboring property that infringed the integrity of a servitude right, the objective being the destruction of what had been done, as long as the work had not been completed. In order to exercise this injunction, the plaintiff had to have previously made a complaint to the builder of the new work (novi operis nuntiatio). When the complaint was accepted by the magistrate, the latter required the defendant to provide a bond of indemnity in the event that he was defeated in the vindicatio servitutis to be exercised by the plaintiff. If this bond was not granted, the interdict would proceed, and the magistrate would then defend the plaintiff who prevented the work from proceeding against the interdict uti possidetis of the builder. However, if the surety was given, the magistrate dispensed with the denunciation (nuntiatio remissa) and the result of the real action was awaited.[9]

Constitution

[edit]The most frequent way of constituting an easement was the in iure cessio in a vindicatio servitutis initiated by the owner of the future dominant estate against the owner of the future servient estate; it was also common for it to be constituted by means of a vindicatory legacy or judicial adjudication. Regarding the ancient servitudes of passage and water conduction on Italian estates, it is worth mentioning that these could be acquired by mancipation, as they were considered res mancipi as well as the estates between which they were established. The servitudes could be usucapted until the so-called Scribonia law appeared (issued in the 1st century B.C., it suppressed the possibility of usucapting servitudes in order to prevent them from being consolidated due to negligence or absence of the owners). However, usucaption was maintained in those cases of recovery of an extinguished servitude due to disuse. Meanwhile, in the provincial estates, servitudes were often constituted through written agreements accompanied by a stipulatio, generally penal (pactiones et stipulationes).[10][11][12][13]

The constitution of servitudes could take place in a direct or indirect way. That is to say, it was also permissible the constitution of the same by means of the reservation of the same in an act of alienation of the property, either in an act of disposition inter vivos or mortis causa.[14][8]

Extinction

[edit]There were several cases that led to the extinction of established servitudes: first, when the two properties (servient and dominant) were completely owned by the same owner, the servitude disappeared by virtue of a principle that stated that there could not be an servitude on one's own property. In short, the extinction of the easement was produced by confusion.[15]

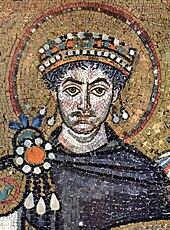

Secondly, the servitude was extinguished by a renunciation of the holder, by means of the use of an in iure cessio in a negatory action. It was also extinguished by disuse or lack of prohibition with respect to acts contrary to a negative action, for a period of two years (with Justinian I the term was increased to ten years, as was the longi temporis praescriptio). Finally, the servitude was extinguished by loss of the utility of the service as a result of a change in the property, definitive flooding, and in general, any other phenomenon leading to the uselessness of the same (in some cases, as happened when the course of a river withdrew from a property it had been occupying permanently or when the confusion of the property disappeared, the servitudes could be reestablished).[16]

See also

[edit]- Condominium

- Usufruct

- Traditio (Law)

- Easement

Bibliography

[edit]- García Garrido, Manuel Jesús (1986). Diccionario de jurisprudencia romana (in Spanish). Dykinson. ISBN 84-86133-16-5.

- D´Ors, Álvaro (2004). Derecho privado romano (in Spanish). EUNSA. ISBN 978-84-313-2233-5.

- Betancourt, Fernando (2007). Derecho romano clásico (in Spanish). Universidad de Sevilla. ISBN 978-84-472-1099-2.

References

[edit]- ^ D'Ors, p. 265 - 266.

- ^ Betancourt, p. 347.

- ^ D'Ors, p. 267.

- ^ D'Ors, p. 268.

- ^ D'Ors, p. 269.

- ^ a b D'Ors, p. 270.

- ^ D'Ors, p. 270 - 271.

- ^ a b Betancourt, p. 352.

- ^ D'Ors, p. 271 - 272.

- ^ D'Ors, p. 272 - 273.

- ^ García Garrido, p. 221.

- ^ Betancourt, p. 351 - 352.

- ^ Carreño, "Pactionibus et stipulationibus". Contribución al estudio de la constitución de servidumbres prediales en el Derecho Romano clásico. (in Spanish) Doctoral dissertation: http://www.tesisenred.net/handle/10803/34763

- ^ D'Ors, p. 273.

- ^ D'Ors, p. 273 - 274

- ^ D'Ors, p. 274