Catholic Church in the Philippines

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2011) |

Catholic Church in the Philippines | |

|---|---|

| Simbahang Katoliko sa Pilipinas (Filipino) | |

| |

| Type | National polity |

| Classification | Catholic |

| Orientation | Latin |

| Scripture | Bible |

| Theology | Catholic theology |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Governance | Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines |

| Pope | Francis |

| President | Pablo Virgilio S. David |

| Apostolic Nuncio | Charles John Brown |

| Region | Philippines |

| Language | Latin, Filipino, Native Philippine regional languages, English, Spanish |

| Headquarters | Intramuros, Manila |

| Origin | March 17, 1521 Spanish East Indies, Spanish Empire |

| Branched from | Catholic Church in Spain |

| Separations | Apostolic Catholic Church (1992) |

| Members | 85.7 million (2020)[1] |

| Tertiary institutions | See list |

| Seminaries | San Carlos Seminary, San Jacinto Seminary |

| Other name(s) |

|

| Official website | www www |

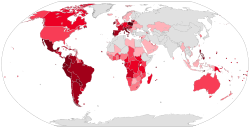

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church by country |

|---|

|

|

|

As part of the worldwide Catholic Church, the Catholic Church in the Philippines (Filipino: Simbahang Katolika sa Pilipinas, Spanish: Iglesia católica en Filipinas), or the Philippine Catholic Church or Philippine Roman Catholic Church, is part of the world's largest Christian church under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome. The Philippines is one of the two nations in Asia having a substantial portion of the population professing the Catholic faith, along with East Timor, and has the third largest Catholic population in the world after Brazil and Mexico.[2] The episcopal conference responsible in governing the faith is the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines (CBCP).

Christianity, through Catholicism, was first brought to the Philippine islands by Spanish pirates, missionaries and settlers, who arrived in waves beginning in the early 16th century in Cebu by way of colonization. Catholicism served as the country's state religion during the Spanish colonial period; since the American colonial period, the faith today is practiced in the context of a secular state. In 2020, it was estimated that 85.7 million Filipinos, or roughly 78.8% of the population, profess the Catholic faith.[1]

History

[edit]Spanish Era

[edit]

Starting in the 16th century Spanish pirates and settlers arrived in the Philippines with two major goals: to participate in the spice trade which was previously dominated by Portugal, and to evangelize nearby civilizations, such as China.[citation needed] While many historians claim that the first Catholic Mass in the islands was held on Easter Sunday, March 31, 1521, on a small island near the present day Bukidnon Province, the exact location is disputed. A verified Mass was held at the island-port of Mazaua (present-day Limasawa) as recorded by the Venetian diarist Antonio Pigafetta, who travelled to the islands in 1521 on the Spanish expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan.[failed verification][3]

Later, the Legazpi expedition of 1565 that was organized from Mexico City marked the beginning of the Hispanisation of the Philippines, beginning with Cebu.[4] This expedition was an effort to occupy the islands with as little conflict as possible, ordered by Phillip II.[5] Lieutenant Legazpi set up colonies in an effort to make peace with the natives[6] and achieve swift conquest.

Christianity expanded from Cebu when the remaining Spanish missionaries were forced westwards due to conflict with the Portuguese, and laid the foundations of the Christian community in the Panay between around 1560 to 1571. A year later the second batch of missionaries reached Cebu. The island became the ecclesiastical "seat" and the center for evangelization. Missionary Fray Alfonso Jimenez OSA traveled into the Camarines region through the islands of Masbate, Leyte, Samar, and Burias and centered the church on Naga City. He was named the first apostle of the region. By 1571 Fray Herrera, who was assigned as chaplain of Legazpi, advanced further north from Panay and founded the local church community in Manila. Herrera travelled further in the Espiritu Santo and shipwrecked in Catanduanes, where he died attempting to convert the natives. In 1572, the Spaniards led by Juan de Salcedo marched north from Manila with the second batch of Augustinian missionaries and pioneered the evangelization in the Ilocos (starting with Vigan) and the Cagayan regions.[4]

Under the encomienda system, Filipinos had to pay tribute to the encomendero of the area, and in return the encomendero taught them the Christian faith and protected them from enemies. Although Spain had used this system in America, it did not work as effectively in the Philippines, and the missionaries were not as successful in converting the natives as they had hoped. In 1579, Bishop Salazar and clergymen were outraged because the encomenderos had abused their powers. Although the natives were resistant, they could not organize into a unified resistance towards the Spaniards, partly due to geography and ethno-linguistic differences.

Cultural impact

[edit]

The Spaniards were disapproving of the lifestyle they observed in the natives. They blamed the influence of the Devil and desired to "liberate the natives from their evil ways". Over time, geographical limitations had shifted the natives into barangays, small kinship units consisting of about 30 to 100 families.

Each barangay had a mutable caste system, with any sub-classes varying from one barangay to the next. Generally, patriarchal lords and kings were called datus and rajas, while the mahárlika were the knight-like freedmen and the timawa were freedmen. The alipin or servile class were dependent on the upper classes, an arrangement regarded as slavery by the Spaniards. Intermarriage between the timawa and the alipin was permitted, which created a more or less flexible system of privileges and labor services. The Spaniards attempted to suppress this class system based on their interpretation that the dependent, servile class was an oppressed group. They failed at completely abolishing the system, but instead eventually worked to use it to their own advantage.

Religion and marriage were also issues that the Spanish missionaries wanted to reform. Polygyny was not uncommon, but was mostly confined to wealthier chieftains. Divorce and remarriage were also common as long as the reasons were justified. Accepted reasons for divorce included illness, infertility, or finding better potential to take as a spouse. The missionaries also disagreed with the practices of paying dowries, the "bride price" where the groom paid his father-in-law in gold, and "bride-service", in which the groom performed manual labor for the bride's family, a custom which persisted until the late 20th century. Missionaries disapproved of these because they felt bride-price was an act of selling one's daughter, and labor services in the household of the father allowed premarital sex between the bride and groom, which contradicted Christian beliefs.

Pre-conquest, the natives had followed a variety of monotheistic and polytheistic faiths, often localized forms of Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam or Tantrism mixed with Animism. Bathala (Tagalog – Central Luzon) or Laon (Visayan) was the ultimate creator deity above subordinate gods and goddesses. Natives Filipinos also worshiped nature and venerated the spirits of their ancestors, whom they propitiated with sacrifices. There was ritualistic drinking and many rituals aimed to cure certain illnesses. Magic and superstition were also practiced. The Spaniards saw themselves as liberating the natives from sinful practices and showing them the correct path to God.

In 1599, negotiation began between a number of lords and their freemen and the Spaniards. The native rulers agreed to submit to the rule of the Castilian king and convert to Christianity, and allow missionaries to spread the faith. In return, the Spaniards agreed to protect the natives from their enemies, mostly Japanese, Chinese, and Muslim pirates.

Difficulties

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

Several factors slowed the Spaniards' attempts to spread Christianity throughout the archipelago. The low number of missionaries on the island made it difficult to reach all the people and harder to convert them. This was also due to the fact that the route to the Philippines was a rigorous journey, and some clergy fell ill or waited years for an opportunity to travel there. For others, the climate difference once they arrived was unbearable. Other missionaries desired to go to Japan or China instead and some who remained were more interested in mercantilism. The Spaniards also came into conflict with the Chinese population in the Philippines. The Chinese had set up shops in the Parian (or bazaar) during the 1580s to trade silk and other goods for Mexican silver. The Spaniards anticipated revolts from the Chinese and were constantly suspicious of them. The Spanish government was highly dependent on the influx of silver from Mexico and Peru, since it supported the government in Manila, to continue the Christianization of the archipelago.

The most difficult challenges for the missionaries were the dispersion of the Filipinos and the wide variety of languages and dialects. The geographical isolation forced the Filipino population into numerous small villages, and every other province supported a different language. Furthermore, frequent privateering from Japanese Wokou pirates and slave-raiding by Muslims blocked Spanish attempts to Christianize the archipelago, and to offset the disruption of continuous warfare with them, the Spanish militarized the local populations, importing soldiers from Latin America, and constructed networks of fortresses across the islands.[7] As the Spanish and their local allies were in a state of constant war against pirates and slavers, the Philippines became a drain on the Vice-royalty of New Spain in Mexico City, which paid to maintaining control of Las Islas Filipinas in lieu of the Spanish crown.

Religious orders

[edit]

The Philippines is home to many of the world's major religious congregations, these include the Rogationists of the Heart of Jesus, the Redemptorists, Augustinians, Recollects, Jesuits, Dominicans, Benedictines, Franciscans, Carmelites, Divine Word Missionaries, De La Salle Christian Brothers, Salesians of Don Bosco, the indigenous Religious of the Virgin Mary, and Clerics Regular of St. Paul are known as Barnabites.

During the Spanish colonial period, the five earliest regular orders assigned to Christianize the natives were the Augustinians, who came with Legazpi, the Discalced Franciscans (1578), the Jesuits (1581), the Dominican friars (1587) and the Augustinian Recollects (simply called the Recoletos, 1606).[8] In 1594, all had agreed to cover a specific area of the archipelago to deal with the vast dispersion of the natives. The Augustinians and Franciscans mainly covered the Tagalog country while the Jesuits had a small area. The Dominicans encompassed the Parian. The provinces of Pampanga and Ilocos were assigned to the Augustinians. The province of Camarines went to the Franciscans. The Augustinians and Jesuits were also assigned the Visayan Islands. The Christian conquest had not reached[citation needed] Mindanao due to a highly resistant Muslim community that existed pre-conquest.

The task of the Spanish missionaries, however, was far from complete. By the seventeenth century, the Spaniards had created about 20 large villages and almost completely transformed the native lifestyle. For their Christian efforts, the Spaniards justified their actions by claiming that the small villages were a sign of barbarism and only bigger, more compact communities allowed for a richer understanding of Christianity. The Filipinos faced much coercion; the Spaniards knew little of native rituals. The layout of these villages was in gridiron form that allowed for easier navigation and more order. They were also spread far enough to allow for one cabecera or capital parish, and small visita chapels located throughout the villages in which clergy only stayed temporarily for Mass, rituals, or nuptials.

The Philippines served as a base for sending missions to other Asian and Pacific countries such as China, Japan, Formosa, Indochina, and Siam.[8]

Indigenous resistance

[edit]This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Filipinos to an extent resisted Christianisation because they felt an agricultural obligation and connection with their rice fields: large villages took away their resources and they feared the compact environment. This also took away from the encomienda system that depended on land, therefore, the encomenderos lost tributes. However, the missionaries continued their proselytising efforts, one strategy being targeting noble children. These scions of now-tributary monarchs and rulers were subjected to intense education in religious doctrine and the Spanish language, with the theory that they in turn could convert their elders, and eventually the nobleman's subjects.

Despite the progress of the Spaniards, it took many years for the natives to truly grasp key concepts of Christianity. In Catholicism, four main sacraments attracted the natives but only for ritualistic reasons, and they did not fully alter their lifestyle as the Spaniards had hoped. Baptism was believed to simply cure ailments, while Matrimony was a concept many natives could not understand and thus they violated the sanctity of monogamy. They were, however, allowed to keep the tradition of dowry, which was accepted into law; "bride-price" and "bride-service" were practiced by natives despite labels of heresy. Confession was required of everyone once a year, and the clergy used the confessionario, a bilingual text aid, to help natives understand the rite's meaning and what they had to confess. Locals were initially apprehensive, but gradually used the rite to excuse excesses throughout the year. Communion was given out selectively, for this was one of the most important sacraments that the missionaries did not want to risk having the natives violate. To help their cause, evangelism was done in the native language.

The Doctrina Christiana is a book of catechism, the alphabet, and basic prayers in Tagalog (both in the Latin alphabet and Baybayin) and Spanish published in the 16th century.

American period: 1898–1946

[edit]

When the Spanish clergy were driven out in 1898, there were so few indigenous clergy that the Catholic Church in the Philippines was in imminent danger of complete ruin. Under American administration, the situation was saved and the proper training of Filipino clergy was undertaken.[9] In 1906, Jorge Barlin was consecrated as the Bishop of Nueva Caceres, making him the first Filipino bishop of the Catholic Church.[10]

During the sovereignty of the United States, the American government implemented the separation of church and state,[11] which reduced the significant political power exerted by the Catholic Church[11] and led to the establishment of other faiths (particularly Protestantism) within the country.[12] A provision of the 1935 Philippine Constitution mimicked the First Amendment to the United States Constitution and added the sentences: "The exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall be forever allowed. No religious test shall be required for the exercise of civil political rights." But the Philippine experience has shown that this theoretical wall of separation has been crossed several times by secular authorities and culturally the Western church and state separation has been viewed as blasphemous among the Filipino people.[tone]

It was during the American Period when newer religious orders arrived in the Philippines. The Spanish friars gradually fled by the hundreds and left parishes without pastors. This prompted bishops to ask for non-Spanish Religious Congregations to set up foundations in the Philippines and help augment the lack of pastors. The American Jesuits and other religious orders from their American province filled the void left by their Spanish counterparts, creating a counterbalance to the growth of Protestant congregations by American Protestant missionaries.[citation needed]

1946–present

[edit]

After the war, most of the religious orders resumed their ecclesiastical duties and helped in the rehabilitation of towns and cities ravaged by war. Classes in Catholic schools run by religious orders resumed, with American priests specializing in academic and scientific fields fulfilling faculty roles until the mid-1970s. American and foreign bishops were gradually succeeded by Filipino bishops by the 1950s.[citation needed]

The Second Vatican Council from 1962 to 1965 instituted a dramatic change for the Catholic Church in the Philippines, transforming the Latin Spanish church imposed upon the country to a Filipino church deeply rooted in Philippine culture and language.[13]

When the Philippines was placed under Martial Law by 10th president and dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr., relations between Church and State changed dramatically, as some bishops expressly and openly opposed Martial Law.[14] The turning point came in 1986 when the CBCP President and then-Archbishop of Cebu Cardinal Ricardo Vidal appealed to the Filipinos and the bishops against the government and the fraudulent result of the snap election;[15] with him was then-Archbishop of Manila Cardinal Jaimé Sin, who broadcast over church-owned Radio Veritas a call for people to support anti-regime rebels. The people's response became what is now known as the People Power Revolution, which ousted Marcos.[16]

Church and State today maintain generally cordial relations despite differing opinions over specific issues. With the guarantee of religious freedom in the Philippines, the Catholic clergy subsequently remained in the political background as a source of moral influence, especially during elections. Political candidates continue to court the clergy and religious leaders for support.[citation needed] In the 21st century, Catholic practice ranges from traditional orthodoxy, to Folk Catholicism and Charismatic Catholicism.[17][failed verification]

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Mass gatherings were prohibited as part of community quarantines to contain the virus; this prompted the Church to broadcast most liturgical services and spiritual activities through the Internet, television, and radio,[18][19] and the CBCP allowed bishops to dispense the faithful from Sunday obligation. Physical Holy Masses in churches gradually resumed by June at limited capacities,[20] but were suspended multiple times in response to multiple surges of cases between August 2020 and January 2022.[21][22] As quarantine restrictions eased, the CBCP, on October 14, 2022, released a circular encouraging the faithful to resume attending Sunday Masses;[23] since then, several dioceses and archdioceses lifted its dispensations from physical attendance of Masses.[24][25] Despite the setbacks brought by the pandemic, in 2021, the Church celebrated the quincentennial of the arrival of Christianity in the country;[26] the celebrations commemorated the first Mass in the country[27] and the re-enactment of the first Baptism in Cebu City, among others.[28]

In 2024, the Philippine Church marked the declaration of Antipolo Cathedral as the country's first international shrine.[29]

Demographics

[edit]NOTE: This statistics is from Annuario Pontificio (via GCatholic.org) and will be updated year-to-year.

PHILIPPINE CATHOLIC STATISTICS (Per Diocese)

| Jurisdiction | % | Catholics | Population | As of | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archdiocese of Caceres | 89.3% | 1,973,650 | 1,761,509 | 2022 | [30] |

| Diocese of Daet | 91% | 636,202 | 699,478 | 2022 | [31] |

| Diocese of Legazpi | 92.3% | 1,389,658 | 1,505,170 | 2022 | [32] |

| Diocese of Libmanan | 85% | 511,196 | 601,407 | 2022 | [33] |

| Diocese of Masbate | 88.9% | 930,324 | 1,045,988 | 2022 | [34] |

| Diocese of Sorsogon | 93% | 779,900 | 838,600 | 2022 | [35] |

| Diocese of Virac | 95% | 265,162 | 279,118 | 2022 | [36] |

| Archdiocese of Cagayan de Oro | 80.2% | 1,443,993 | 1,799,450 | 2022 | [37] |

| Diocese of Butuan | 79.1% | 1,003,809 | 1,269,529 | 2022 | [38] |

| Diocese of Malaybalay | 77.6% | 1,363,026 | 1,756,058 | 2022 | [39] |

| Diocese of Surigao | 82.1% | 453,963 | 553,231 | 2022 | [40] |

| Diocese of Tandag | 78.6% | 600,144 | 763,780 | 2022 | [41] |

| Archdiocese of Capiz | 90.1% | 828,386 | 918,900 | 2022 | [42] |

| Diocese of Kalibo | 74.7% | 679,400 | 909,900 | 2022 | [43] |

| Diocese of Romblon | 81.4% | 472,660 | 580,485 | 2022 | [44] |

| Archdiocese of Cebu | 86.8% | 4,678,039 | 5,388,718 | 2022 | [45] |

| Diocese of Dumaguete | 88.4% | 1,412,394 | 1,598,455 | 2022 | [46] |

| Diocese of Maasin | 83.5% | 706,966 | 846,620 | 2022 | [47] |

| Diocese of Tagbilaran | 94.3% | 705,898 | 748,916 | 2022 | [48] |

| Diocese of Talibon | 78.3% | 604,548 | 771,795 | 2022 | [49] |

| Archdiocese of Cotabato | 45.6% | 1,108,300 | 2,431,960 | 2022 | [50] |

| Diocese of Kidapawan | 58.5% | 626,150 | 1,069,640 | 2022 | [51] |

| Diocese of Marbel | 79.1% | 1,691,050 | 2,137,340 | 2022 | [52] |

| Archdiocese of Davao | 82.4% | 1,506,873 | 1,829,041 | 2022 | [53] |

| Diocese of Digos | 62.9% | 856,039 | 1,362,021 | 2022 | [54] |

| Diocese of Mati | 62.4% | 369,160 | 591,289 | 2022 | [55] |

| Diocese of Tagum | 73.1% | 1,245,690 | 1,703,438 | 2022 | [56] |

| Archdiocese of Jaro | 83.1% | 3,082,540 | 3,708,350 | 2022 | [57] |

| Diocese of Bacolod | 79% | 1,309,520 | 1,657,620 | 2022 | [58] |

| Diocese of Kabankalan | 80% | 785,657 | 982,071 | 2022 | [59] |

| Diocese of San Carlos | 85.7% | 992,732 | 1,158,670 | 2022 | [60] |

| Diocese of San Jose de Antique | 70.8% | 499,000 | 704,400 | 2022 | [61] |

| Archdiocese of Lingayen-Dagupan | 79% | 1,232,511 | 1,560,927 | 2022 | [62] |

| Diocese of Alaminos | 82.4% | 660,545 | 802,114 | 2022 | [63] |

| Diocese of Cabanatuan | 84.3% | 1,036,081 | 1,228,762 | 2022 | [64] |

| Diocese of San Fernando de La Union | 83% | 690,339 | 831,734 | 2022 | [65] |

| Diocese of San Jose de Nueva Ecija | 69% | 636,422 | 922,351 | 2022 | [66] |

| Diocese of Urdaneta | 81% | 702,058 | 866,340 | 2022 | [67] |

| Archdiocese of Lipa | 97.7% | 3,337,746 | 3,414,937 | 2022 | [68] |

| Diocese of Boac | 88% | 257,064 | 292,019 | 2022 | [69] |

| Diocese of Gumaca | 85% | 909,321 | 1,070,269 | 2022 | [70] |

| Diocese of Lucena | 89% | 939,506 | 1,055,544 | 2022 | [71] |

| Territorial Prelature of Infanta | 76.9% | 373,000 | 485,240 | 2022 | [72] |

| Archdiocese of Manila | 81% | 2,694,960 | 3,327,180 | 2022 | [73] |

| Diocese of Antipolo | 81.5% | 3,144,550 | 3,856,230 | 2022 | [74] |

| Diocese of Cubao | 78.8% | 1,478,766 | 1,877,260 | 2022 | [75] |

| Diocese of Imus | 79.9% | 3,500,260 | 4,381,812 | 2022 | [76] |

| Diocese of Kalookan | 80% | 1,831,719 | 2,289,649 | 2022 | [77] |

| Diocese of Malolos | 82.1% | 3,757,226 | 4,577,850 | 2022 | [78] |

| Diocese of Novaliches | 78% | 2,500,327 | 3,205,547 | 2022 | [79] |

| Diocese of Parañaque | 79.5% | 1,504,036 | 1,891,869 | 2022 | [80] |

| Diocese of Pasig | 87.1% | 1,756,388 | 2,017,214 | 2022 | [81] |

| Diocese of San Pablo | 87.8% | 3,115,119 | 3,547,994 | 2022 | [82] |

| Archdiocese of Nueva Segovia | 83% | 642,183 | 773,834 | 2022 | [83] |

| Diocese of Baguio | 72.6% | 601,130 | 828,190 | 2022 | [84] |

| Diocese of Bangued | 84.8% | 227,532 | 268,438 | 2022 | [85] |

| Diocese of Laoag | 59% | 374,623 | 635,283 | 2022 | [86] |

| Archdiocese of Ozamis | 58.2% | 447,471 | 768,883 | 2022 | [87] |

| Diocese of Dipolog | 69.4% | 726,168 | 1,045,745 | 2022 | [88] |

| Diocese of Iligan | 59.3% | 716,993 | 1,209,061 | 2022 | [89] |

| Diocese of Pagadian | 80.4% | 1,098,000 | 1,366,200 | 2022 | [90] |

| Territorial Prelature of Marawi | 3.7% | 38,800 | 1,039,000 | 2016 | [91] |

| Archdiocese of Palo | 95.9% | 1,519,171 | 1,584,942 | 2022 | [92] |

| Diocese of Borongan | 99% | 472,168 | 477,168 | 2022 | [93] |

| Diocese of Calbayog | 91.9% | 745,592 | 811,630 | 2022 | [94] |

| Diocese of Catarman | 93.9% | 639,679 | 681,299 | 2022 | [95] |

| Diocese of Naval | 86.3% | 336,713 | 390,228 | 2022 | [96] |

| Archdiocese of San Fernando | 85.9% | 2,535,615 | 2,951,705 | 2022 | [97] |

| Diocese of Balanga | 80% | 690,890 | 863,610 | 2022 | [98] |

| Diocese of Iba | 80% | 739,793 | 924,741 | 2022 | [99] |

| Diocese of Tarlac | 67.4% | 1,116,210 | 1,656,200 | 2022 | [100] |

| Archdiocese of Tuguegarao | 79.3% | 1,669,800 | 2,105,970 | 2022 | [101] |

| Diocese of Bayombong | 54.3% | 406,000 | 748,153 | 2022 | [102] |

| Diocese of Ilagan | 70% | 1,187,935 | 1,697,050 | 2022 | [103] |

| Territorial Prelature of Batanes | 94.8% | 18,089 | 19,090 | 2022 | [104] |

| Archdiocese of Zamboanga | 67.2% | 707,170 | 1,052,763 | 2022 | [105] |

| Diocese of Ipil | 75% | 582,608 | 776,811 | 2022 | [106] |

| Territorial Prelature of Isabela | 28.8% | 131,560 | 456,400 | 2022 | [107] |

| Apostolic Vicariate of Bontoc-Lagawe | 60.5% | 221,750 | 366,766 | 2022 | [108] |

| Apostolic Vicariate of Calapan | 92.7% | 931,000 | 1,003,940 | 2022 | [109] |

| Apostolic Vicariate of Jolo | 1.4% | 19,240 | 1,374,259 | 2022 | [110] |

| Apostolic Vicariate of Puerto Princesa | 64.1% | 536,225 | 836,615 | 2022 | [111] |

| Apostolic Vicariate of San Jose in Mindoro | 75.9% | 403,900 | 532,445 | 2022 | [112] |

| Apostolic Vicariate of Tabuk | 75% | 375,000 | 499,800 | 2022 | [113] |

| Apostolic Vicariate of Taytay | 83% | 633,821 | 763,640 | 2022 | [114] |

Internal movements

[edit]Catholic Charismatic Renewal

[edit]

A number of Catholic Charismatic Renewal movements emerged vis-a-vis the Born-again movement during the 70s. The charismatic movement offered In-the-Spirit seminars in the early days, which have now evolved and have different names; they focus on the charismatic gifts of the Holy Spirit. Some of the charismatic movements were the Ang Ligaya ng Panginoon, Assumption Prayer Group, Couples for Christ, the Brotherhood of Christian Businessmen and Professionals, El Shaddai, Elim Communities, Kerygma, the Light of Jesus Family,[115] Shalom, and Soldiers of Christ.[116]

Neocatechumenal Way

[edit]The Catholic Church's Neocatechumenal Way in the Philippines has been established for more than 40 years. Membership in the Philippines now exceeds 35,000 persons in more than 1,000 communities, with concentrations in Manila and Iloilo province. A neocatechumenal diocesan seminary, Redemptoris Mater, is located in Parañaque, while many families in mission are all over the islands. The Way has been mostly concentrated on evangelization initiatives under the authority of the local bishops.

Organization

[edit]

The Catholic Church in the Philippines is organized into 72 dioceses in 16 Ecclesiastical Provinces, as well as 7 Apostolic Vicariates and a Military Ordinariate.

Extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion

[edit]Due to large number of attendees, virtually all Masses in the Philippines employ the use of extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion;[117] commissioning of ministers and renewal of their vows is a regular occurrence.[118][119] In early 2023, claims regarding Freemasons distributing Holy Communion in some parishes prompted the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines to restate its stance on "the unacceptability of Masonry, given its serious errors".[120]

Society

[edit]Education

[edit]

The Catholic Church is involved in education at all levels. It has founded and continues to sponsor hundreds of secondary and primary schools as well as a number of colleges and internationally known universities. The earliest universities in the Philippines were the University of San Carlos and the University of Santo Tomas, founded during the Spanish colonial period.[121] The Jesuit Ateneo de Manila University, La Salle Brothers De La Salle University, and the Dominican University of Santo Tomas are listed in the "World's Best Colleges and Universities" in the Times Higher Education-QS World University Rankings.[122]

Other Catholic educational institutions in the country include the Notre Dame institution system in Mindanao, the Rogationist College in Silang, Cavite, and the Divine Word and Saint Louis school systems in Luzon.[121]

More than 1,500 Catholic schools throughout the Philippines are members of the Catholic Educational Association of the Philippines (CEAP), the national association of Catholic schools in the country founded in 1941.[123]

Politics

[edit]

The Catholic Church wields great influence on Philippine society and politics, notably reaching its political peak in 1986.[124] Then-Archbishops of Cebu and Manila—Cardinals Ricardo Vidal and Jaime Sin, respectively—were influential during the People Power Revolution of 1986 against dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos. Vidal, who was president of the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) at that time, led the rest of the Philippine bishops and made a joint declaration against Marcos and the results of the snap election, while Sin appealed to the public via radio to march along Epifanio delos Santos Avenue in support of rebel forces. Some seven million people responded in the non-violent revolution which lasted from February 22–25, effectively driving Marcos out of power and into exile in Hawaii.[125]

In 1989, President Corazon Aquino asked Vidal to convince General Jose Comendador, who was sympathetic to the rebel forces fighting her government, to peacefully surrender. Vidal's efforts averted what could have been a bloody coup.[126]

In October 2000, Sin expressed his dismay over the allegations of corruption against President Joseph Estrada. His call sparked the second EDSA Revolution, dubbed as "EDSA Dos". Vidal personally asked Estrada to step down, to which he agreed at around 12:20 p.m. of January 20, 2001, after five continuous days of protest at the EDSA Shrine, and various parts of the Philippines and the world. Estrada's Vice-President, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, succeeded him and was sworn in on the terrace of the shrine in front of Sin. However, in 2008, more than halfway into Arroyo's presidency, the Catholic Church apologized, and the CBCP President at the time and the Archbishop of Jaro, Angel Lagdameo, called EDSA II a mistake.[127]

On the death of Pope John Paul II in 2005, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo declared three days of national mourning and was one of many dignitaries at his funeral in Vatican City.[128] Political turmoil in the Philippines widened the rift between the State and the Church. Arroyo's press secretary Ignacio Bunye called the bishops and priests who attended an anti-Arroyo protest as hypocrites and "people who hide their true plans".

The Catholic Church in the Philippines strongly opposed the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012, commonly known as the RH Bill.[129] The country's populace – 80% of which self-identify as Catholic – was deeply divided in its opinions over the issue.[130] Members of the CBCP vehemently denounced and repeatedly attempted to block[131] President Benigno Aquino III's plan to push for the passage of the reproductive health bill.[132][133] The bill, which was popular among the public, was signed into law by Aquino, and was seen as a point of waning moral and political influence of the Catholic Church in the country.[134][131][124]

During the Duterte administration, the Catholic Church in the Philippines was vocally critical of extrajudicial killings taking place during the war on drugs, in what the church sees as the administration's approval of the bloodshed.[135] Efforts by the church to rally public support against the administration's war on drugs were less effective due to Duterte's popularity and high trust rating.[124] Some churches reportedly offered sanctuary to those who fear death due to the drug war violence.[136]

During the 2022 presidential elections campaign, the church supported and endorsed the candidacy of vice president Leni Robredo in an effort to prevent Bongbong Marcos, son of dictator Ferdinand Marcos, from winning the election. Robredo, who won in 18 of the 86 dioceses in the country,[137] lost the presidential race in a landslide.[138]

Missionary activities

[edit]The Philippines has been active in sending Catholic missionaries around the world and has been a training center for foreign priests and nuns.[139]

To spread the Christian religion and the teachings of Jesus Christ, missionaries enter local communities. Depending on where a missionary or group of missionaries are travelling, their work will vary (international or local communities).

Marian devotion

[edit]

The Philippines has shown a strong devotion to Mary, evidenced by her patronage of various towns and locales nationwide.[140] Particularly, there are pilgrimage sites dedicated to a specific apparition or title of Mary. With Spanish regalia, indigenous miracle stories, and Asian facial features, Filipino Catholics have created hybridized, localized images, the popular devotions to which have been recognized by various Popes.

Filipino Marian images with an established devotion have generally received a Canonical Coronation, with the icon's principal shrine being customarily elevated to the status of minor basilica. Below are some pilgrimage sites and the year they received a canonical blessing:

- Our Lady of the Abandoned (Nuestra Señora de los Desamparados) Marikina – 2005

- Our Lady of La Leche (Nuestra Señora de la Leche y Buen Parto) Diocese of Imus, Silang, Cavite

- Our Lady of Aranzazu (Nuestra Señora de Aranzazu) San Mateo, Rizal – 2017

- Our Lady of Bigláng Awà (Nuestra Señora del Pronto Socorro) Boac, Marinduque – 1978

- Our Lady of Caysasay (Nuestra Señora de Caysásay) Taal, Batangas – 1954

- Our Lady of Charity (Nuestra Señora de Caridad) – Basilica Minore of Our Lady of Charity

- Bantay, Ilocos Sur – 1956

- Agoo, La Union – 1971

- Our Lady of the Assumption (Nuestra Señora dela Asuncion) Santa Maria Church, Santa Maria, Ilocos Sur

- Our Lady of Consolation (Nuestra Señora de Consolación y Correa) San Agustin Church, Intramuros, City of Manila

- Our Lady, the Divine Shepherdess (La Virgen Divina Pastora) – Gapan Church, Gapan, Nueva Ecija – 1964

- Our Lady of Namacpacan (Nuestra Señora de Namacpacan) Luna, La Union – 1959

- Our Lady of Buen Suceso (Parañaque) (Nuestra Señora del Buen Suceso de Parañaque) Parañaque – 2005

- Our Lady of Guadalupe (Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe) Pagsanjan, Laguna

- Our Lady of Guadalupe of Cebu (Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Cebú) Cebu City – 2006

- Our Lady of Guidance (Nuestra Señora de Guia) Ermita, City of Manila – 1955

- Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception of Pasig (Nuestra Señora de la Inmaculada Concepción de Pásig) Pasig – 2008

- Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception (Nuestra Señora de La Inmaculada Concepción de Malabón) Malabon – 1986

- Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception (Virgen Inmaculada Concepción de Malolos) Malolos, Bulacan – 2012

- Our Lady of La Naval (Nuestra Señora del Santísimo Rosario de la Naval de Manila) Quezon City – 1907

- Our Lady of Lourdes (Nuestra Señora de Lourdes) Quezon City – 1951

- Our Lady of Manaoag (Nuestra Señora del Santísimo Rosario de Manáoag) Manaoag, Pangasinan – 1926

- Our Lady of Orani (Nuestra Señora del Santo Rosario de Orani) – Orani, Bataan

- Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage (Nuestra Señora de la Paz y Buen Viaje) Antipolo, Rizal – 1926

- Our Lady of Peñafráncia of Naga (Nuestra Señora de Peñafráncia de Naga) Naga City, Camarines Sur – 1924

- Our Lady of Peñafráncia of Manila (Nuestra Señora del Rosario de Río Pásig) Paco, City of Manila – 1985

- Our Lady of Piat (Nuestra Señora de Píat) Piat, Cagayan – 1954

- Our Lady of the Pillar (Nuestra Señora la Virgen del Pilar) Zamboanga City – 1960

- Our Lady of the Pillar of Imus (Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Imus) Imus, Cavite – 2012

- Our Lady of the Pillar of Manila (Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Manila) Santa Cruz, Manila – 2017

- Our Lady of the Rule (Nuestra Señora de la Regla) Opon, Cebu – 1954

- Our Lady of Solitude of Vaga Gate (Nuestra Señora de la Soledad de Porta Vaga) Cavite City

- Our Lady of Sorrows of Turúmba (Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de Turúmba) Pakil, Laguna

- Our Lady of the Candles (Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria) Jaro, Iloilo City

- Our Mother of Perpetual Help (Nuestra Señora del Perpetuo Socorro) Baclaran, Parañaque

- Our Lady of Salvation (Nuestra Señora de la Salvación) Joroan, Tiwi, Albay

- Our Lady of Mercy (Nuestra Señora de la Merced) Novaliches, Quezon City - 2021, Matatalaib, Tarlac City - 2023

- Our Lady of Soterraña de Nieva, currently owned by former First Lady Imelda Marcos

- Virgen de los Remedios de Pampanga (Indu Ning Capaldanan) Archdiocese of San Fernando, Pampanga

- Our Lady of Hope of Palo (Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza) Archdiocese of Palo, Palo, Leyte[141]

- Our Lady of the Rose of Makati (Nuestra Señora de la Rosa de Macati) Archdiocese of Manila, Población, Makati

Religious observances

[edit]Catholic holy days, such as Christmas and Good Friday, are observed as national holidays,[142] with local saints' days being observed as holidays in different towns and cities. The Hispanic-influenced custom of holding fiestas in honor of patron saints have become an integral part of Filipino culture, as it allows for communal celebration while serving as a celebration of the town's existence.[143][144] A nationwide fiesta occurs on the third Sunday in January, on the country-specific Feast of the Santo Niño de Cebú. Major festivals include Sinulog in Cebu City, Ati-Atihan in Kalibo, Aklan, and Dinagyang in Iloilo City.[145][146][147]

Although the Catholic Church observes ten holy days of obligation, the Philippines only observes three. These are:[148]

- December 8: Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary

- December 25: Christmas (The Nativity of the Lord)

- January 1: Solemnity of Mary, the Holy Mother of God

Filipino diaspora

[edit]Overseas Filipinos have spread Filipino culture worldwide, bringing Filipino Catholicism with them.[149] Filipinos have established two shrines in the Chicago Metropolitan Area: one at St. Wenceslaus Church dedicated to Santo Niño de Cebú and another at St. Hedwig's with its statue to Our Lady of Manaoag. The Filipino community in the Archdiocese of New York has the San Lorenzo Ruiz Chapel (New York City) for its apostolate.

Papal visits

[edit]

- Pope Paul VI (1970) was the target of an assassination attempt at Manila International Airport in the Philippines in 1970.[150] The assailant, a Bolivian surrealist painter named Benjamín Mendoza y Amor Flores, lunged toward Pope Paul with a kris, but was subdued.[150]

- Pope John Paul II (1981 and 1995) returned for World Youth Day 1995 which was reported to have an attendance of around five million Filipino and foreign people in Rizal Park.[151][152]

- Pope Francis (2015) visited the country on January 15–19, 2015, and was invited by Manila Archbishop Luis Antonio Tagle to return for the International Eucharistic Congress in Cebu in 2016.[153][154] At the Mass at Manila's Quirino Grandstand inside Rizal Park on Sunday, January 18, 2015, the attendance was pegged at about six to seven million worshippers, making the event the highest number ever recorded in papal history according to Fr. Federico Lombardi, director of the Vatican Press Office.[155]

See also

[edit]- Christmas in the Philippines

- Holy Week in the Philippines

- Spanish influence on Filipino culture

- Freedom of religion in the Philippines

- List of Filipino Saints, Blesseds, and Servants of God

- List of Catholic churches in the Philippines

References

[edit]- ^ a b Yraola, Abigail Marie P. (February 22, 2023). "Catholics make up nearly 79% of Philippine population". BusinessWorld. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ^ "Philippines still top Christian country in Asia, 5th in world". Inquirer Global Nation. December 21, 2011.

- ^ "History of Cebu | Philippines Cebu Island History | Cebu City Tour". May 17, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ a b "Cebu - Cradle of the Philippine Church and Seat of Far-East Christianity." International Eucharistic Congress 2016, December 4, 2014, accessed December 4, 2014, http://iec2016.ph/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Cebu%E2%80%94Cradle-of-the-Philippine-Church-and-Seat-of-Far-East-Christianity.pdf

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-135-4.

- ^ "The Legazpi Expedition". Stuart Exchange. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- ^ "Spanish Fortifications". filipinokastila.tripod.com. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ a b Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. p. 524. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Donald Attwater. "A Catholic Dictionary", s.v. "PHILIPPINES, THE CHURCH IN THE". 1958. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Ross, Kenneth R. (February 3, 2020). Christianity in East and Southeast Asia. Edinburgh University Press. p. 382. ISBN 978-1-4744-5162-8. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Sahliyeh, Emile F. (January 1, 1990). Religious Resurgence and Politics in the Contemporary World. SUNY Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-7914-0381-5. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Living Faith in God Iii / Becoming a Community. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 119. ISBN 978-971-23-2388-1. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Amarante, Dennis C. (2022). "A Survey of Literatures on Post-Vatican II Liturgical Reforms in the Philippines". Philippiniana Sacra. LVII (173). University of Santo Tomas: 276,278. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Bacani 1987, p. 75.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (February 15, 1986). "Philippine Bishops Assail Vote Fraud and Urge Protest". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Fineman, Mark (February 27, 1986). "The 3-Day Revolution: How Marcos Was Toppled". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "Filipinos as Christians". Camperspoint Philippines. February 17, 2004. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ Soliman, Michelle Anne P. (March 18, 2020). "Virtual religious gatherings amidst COVID-19". bworldonline.com. BusinessWorld Online. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ^ "Mass livestream, alcohol at church entrances as Manila archdiocese guards against COVID-19". ABS-CBN News. March 9, 2020. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Aquino, Leslie Ann; Aro, Andrea (June 6, 2020). "Quiapo Church resumes 1st Friday mass service with 10 devotees". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved March 17, 2023 – via PressReader.

- ^ Depasupil, William B. (August 5, 2020). "Public Masses suspended during MECQ". The Manila Times. Retrieved March 17, 2023 – via PressReader.

- ^ Kabagani, Lade Jean (January 5, 2022). "NTF OKs suspension of Traslacion 2022, physical masses". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ Ramirez, Robertzon (October 15, 2022). "CBCP To Faithful: Return To Face-To-Face Sunday Mass". One News. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ Naval, Gerard (April 3, 2023). "In-church Masses resume in Cubao diocese". Malaya Business Insight. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ "Malolos Bishop Villarojo to lift dispensation on attending Sunday masses". GMA Integrated News. May 29, 2023. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ Esmaquel, Paterno II (April 4, 2021). "Bishops open Jubilee Doors to mark 500 years of Christianity in PH". Rappler. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Gabieta, Joey (March 31, 2021). "First Easter Mass in PH commemorated on Limasawa Island". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Erram, Morexette Marie (April 14, 2021). "Cebu holds reenactment of First Baptism with face shields and masks". Cebu Daily News. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Santos, Jamil (January 26, 2024). "Bishops, devotees mark declaration of Antipolo Cathedral as international shrine". GMA Integrated News. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Caceres latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Daet latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Legazpi latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Libmanan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Masbate latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Sorsogon latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Virac latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Cagayan De Oro latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Butuan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Malaybalay latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Surigao latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Tandag latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Capiz latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Kalibo latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Romblon latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Cebu latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Dumaguete latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Maasin latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Tagbilaran latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Talibon latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Cotabato latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Kidapawan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Marbel latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Davao latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Digos latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Mati latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Tagum latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Jaro latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Bacolod latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Kabankalan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Kabankalan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of San Jose de Antique latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Lingayen-Dagupan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Alaminos latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Cabanatuan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of San Fernando de La Union latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of San Jose de Nueva Ecija latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Urdaneta latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Lipa latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Boac latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Gumaca latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Lucena latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Territorial Prelature of Infanta latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Manila latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Antipolo latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Cubao latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Imus latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Kalookan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Malolos latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Novaliches latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Parañaque latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Pasig latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of San Pablo latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Nueva Segovia latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Baguio latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Bangued latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Laoag latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Ozamis latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Dipolog latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Iligan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Pagadian latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Territorial Prelature of Marawi latest statistics (2016)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Palo latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Borongan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Calbayog latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Catarman latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Naval latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of San Fernando latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Balanga latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Iba latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Tarlac latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Tuguegarao latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Bayombong latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Ilagan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Territorial Prelature of Batanes latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Zamboanga latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Diocese of Ipil latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Territorial Prelature of Isabela latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Apostolic Vicariate of Bontoc-Lagawe latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Apostolic Vicariate of Calapan latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Apostolic Vicariate of Jolo latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Apostolic Vicariate of Puerto Princesa latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Apostolic Vicariate of San Jose in Mindoro latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Apostolic Vicariate of Tabuk latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Apostolic Vicariate of Taytay latest statistics (2022)". gcatholic. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ builder. "home". Feast Family. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Soldiers Of Christ Catholic Charismatic Healing Ministry Official". www.facebook.com. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ McNamara, Fr. Edward (November 5, 2019). "Extraordinary Ministers' Limits". EWTN. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ Ortega, Rocky (June 4, 2018). "Exraordinary Ministers Of The Holy Communion renewed their vows of service and commitment". Shrine & Parish of Our Lady of Aranzazu. Archived from the original on September 3, 2024. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ Odivilas, Joseph (October 12, 2021). "Commissioning of Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion". Don Bosco Philippines South Province. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ "Philippine bishops warn against 'Catholic-Freemasons'". Union of Catholic Asian News. March 28, 2023. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Welch, Anthony (March 31, 2011). Higher Education in Southeast Asia: Blurring Borders, Changing Balance. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-80906-4. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ Top Universities Archived January 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "About Us". Catholic Educational Association of the Philippines. Archived from the original on May 8, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c Maresca, Thomas (April 29, 2017). "Catholic Church dissents on Duterte's drug war". USA Today. pp. 4B. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ^ "Briefly In Religion". Los Angeles Times. October 6, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "Cardinal Vidal says dialogue helped limit bloodshed during coup". Union of Catholic Asian News. December 11, 1989. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Ayen Infante (February 20, 2008). "Edsa II a mistake, says CBCP head". The Daily Tribune. Philippines. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ Calica, Aurea (April 5, 2005). "GMA set to leave for Rome; RP starts 3-day mourning". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on December 27, 2023. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ^ "Church to continue opposition vs RH bill passage". SunStar. August 16, 2011. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

- ^ Dentsu Communication Institute Inc., Research Centre Japan (2006)(in Japanese)

- ^ a b "Philippines contraception law signed by Benigno Aquino". BBC News. December 29, 2012. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Macairan, Evelyn (December 16, 2012). "'Fight vs RH bill is Catholic Church's biggest challenge'". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- ^ Tubeza, Philip C. (July 25, 2012). "Aquino's RH bill endorsement an open war on Church, bishops say". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- ^ "Power of the Catholic Church slipping in Philippines". Christian Science Monitor. March 6, 2013. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Neuman, Scott (August 20, 2017). "Church Leaders In Philippines Condemn Bloody War On Drugs". National Public Radio. United States. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ Watts, Jake Maxwell; Aznar, Jes (July 5, 2018). "Catholic Church Opens Sanctuaries to the Hunted in Philippines Drug War". Wall Street Journal. United States. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ Saludes, Mark (June 29, 2022). "Catholic nation? The Filipino Church rethinks its role in politics". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022.

- ^ Buan, Lian (May 9, 2022). "36 years after ousting Marcos, Filipinos elect son as president". Rappler. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ^ "Religious and lay Filipino missionaries in the world are "Christ first witnesses". AsiaNews. July 16, 2015. Archived from the original on April 23, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

With a Christian tradition that goes back almost 500 years, the Philippines has not only sent a large number of missionaries abroad, especially in Europe, but has also become a training centre for hundreds of priests, seminarians and nuns from all over the world.

- ^ "Filipinos hold Grand Marian Procession ahead of Mary's feast". December 2, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Our Lady of Hope of Palo crowned November 8 in Leyte". Inquirer. November 9, 2022. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ gov.ph

- ^ Rodell, Paul A. (2002). Culture and Customs of the Philippines. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-313-30415-6. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Mildenstein, Tammy; Stier, Samuel Cord; Gritzner, Charles F. (2009). Philippines. Infobase Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4381-0547-5. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ International Consumer Product Testing Across Cultures and Countries. ASTM International. p. 130. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Werbner, Pnina; Johnson, Mark (July 9, 2019). Diasporic Journeys, Ritual, and Normativity among Asian Migrant Women. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-98323-1. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Reyes, Elizabeth V. (May 10, 2016). Philippines: A Visual Journey. Tuttle Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4629-1856-0. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Balinbin, Arjay L. (December 30, 2017). "December 8 a special non-working holiday every year". BusinessWorld. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ^ "Filipino Diaspora: Modern-day Missionaries of the World". Omnis Terra. Agenzia Fides. April 19, 2018. Archived from the original on April 19, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ a b "Apostle Endangered". Time, December 7, 1970. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

- ^ AsiaNews.it. "The Philippines, 1995: Pope dreams of". www.asianews.it. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ Service, New York Times News (January 16, 1995). "Millions flock to papal Mass in Manila Gathering is called the largest the pope has seen at a service". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "CBCP: Pope Francis may visit Philippines in 2016". The Philippine STAR. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ^ "Pope Francis invited to Cebu event in 2016 - Tagle". philstar.com. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ ABS-CBNnews.com, Jon Carlos Rodriguez (January 18, 2015). "'Luneta Mass is largest Papal event in history'". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- This article incorporates material from the U.S. Library of Congress and is available to the general public.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bacani, Teodoro (1987). The Church and Politics. Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines: Clarentian Publications. ISBN 978-971-501-172-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Bautista, Julius (August 24, 2015). "EXPORT-QUALITY MARTYRS: Roman Catholicism and Transnational Labor in the Philippines". Cultural Anthropology. 30 (3): 424–447. doi:10.14506/ca30.3.04.