Rod cell

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

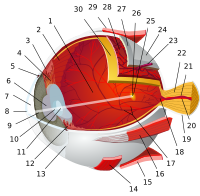

| Rod cell | |

|---|---|

Cross section of the retina. Rods are visible at far right. | |

| Details | |

| Location | Retina |

| Shape | Rod-shaped |

| Function | Low-light photoreceptor |

| Neurotransmitter | Glutamate |

| Presynaptic connections | None |

| Postsynaptic connections | Bipolar cells and horizontal cells |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D017948 |

| NeuroLex ID | nlx_cell_100212 |

| TH | H3.11.08.3.01030 |

| FMA | 67747 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Rod cells are photoreceptor cells in the retina of the eye that can function in lower light better than the other type of visual photoreceptor, cone cells. Rods are usually found concentrated at the outer edges of the retina and are used in peripheral vision. On average, there are approximately 92 million rod cells (vs ~6 million cones) in the human retina.[1] Rod cells are more sensitive than cone cells and are almost entirely responsible for night vision. However, rods have little role in color vision, which is the main reason why colors are much less apparent in dim light.

Structure

[edit]Rods are a little longer and leaner than cones but have the same basic structure. Opsin-containing disks lie at the end of the cell adjacent to the retinal pigment epithelium, which in turn is attached to the inside of the eye. The stacked-disc structure of the detector portion of the cell allows for very high efficiency. Rods are much more common than cones, with about 120 million rod cells compared to 6 to 7 million cone cells.[2]

Like cones, rod cells have a synaptic terminal, an inner segment, and an outer segment. The synaptic terminal forms a synapse with another neuron, usually a bipolar cell or a horizontal cell. The inner and outer segments are connected by a cilium,[3] which lines the distal segment.[4] The inner segment contains organelles and the cell's nucleus, while the rod outer segment (abbreviated to ROS), which is pointed toward the back of the eye, contains the light-absorbing materials.[3]

A human rod cell is about 2 microns in diameter and 100 microns long.[5] Rods are not all morphologically the same; in mice, rods close to the outer plexiform synaptic layer display a reduced length due to a shortened synaptic terminal.[6]

Function

[edit]Photoreception

[edit]

In vertebrates, activation of a photoreceptor cell is a hyperpolarization (inhibition) of the cell. When they are not being stimulated, such as in the dark, rod cells and cone cells depolarize and release a neurotransmitter spontaneously. This neurotransmitter hyperpolarizes the bipolar cell. Bipolar cells exist between photoreceptors and ganglion cells and act to transmit signals from the photoreceptors to the ganglion cells. As a result of the bipolar cell being hyperpolarized, it does not release its transmitter at the bipolar-ganglion synapse and the synapse is not excited.

Activation of photopigments by light sends a signal by hyperpolarizing the rod cell, leading to the rod cell not sending its neurotransmitter, which leads to the bipolar cell then releasing its transmitter at the bipolar-ganglion synapse and exciting the synapse.

Depolarization of rod cells (causing release of their neurotransmitter) occurs because in the dark, cells have a relatively high concentration of cyclic guanosine 3'-5' monophosphate (cGMP), which opens ion channels (largely sodium channels, though calcium can enter through these channels as well). The positive charges of the ions that enter the cell down its electrochemical gradient change the cell's membrane potential, cause depolarization, and lead to the release of the neurotransmitter glutamate. Glutamate can depolarize some neurons and hyperpolarize others, allowing photoreceptors to interact in an antagonistic manner.

When light hits photoreceptive pigments within the photoreceptor cell, the pigment changes shape. The pigment, called rhodopsin (conopsin is found in cone cells) comprises a large protein called opsin (situated in the plasma membrane), attached to which is a covalently bound prosthetic group: an organic molecule called retinal (a derivative of vitamin A). The retinal exists in the 11-cis-retinal form when in the dark, and stimulation by light causes its structure to change to all-trans-retinal. This structural change causes an increased affinity for the regulatory protein called transducin (a type of G protein). Upon binding to rhodopsin, the alpha subunit of the G protein replaces a molecule of GDP with a molecule of GTP and becomes activated. This replacement causes the alpha subunit of the G protein to dissociate from the beta and gamma subunits of the G protein. As a result, the alpha subunit is now free to bind to the cGMP phosphodiesterase (an effector protein).[8] The alpha subunit interacts with the inhibitory PDE gamma subunits and prevents them from blocking catalytic sites on the alpha and beta subunits of PDE, leading to the activation of cGMP phosphodiesterase, which hydrolyzes cGMP (the second messenger), breaking it down into 5'-GMP.[9] Reduction in cGMP allows the ion channels to close, preventing the influx of positive ions, hyperpolarizing the cell, and stopping the release of the neurotransmitter glutamate.[3] Though cone cells primarily use the neurotransmitter substance acetylcholine, rod cells use a variety. The entire process by which light initiates a sensory response is called visual phototransduction.

Activation of a single unit of rhodopsin, the photosensitive pigment in rods, can lead to a large reaction in the cell because the signal is amplified. Once activated, rhodopsin can activate hundreds of transducin molecules, each of which in turn activates a phosphodiesterase molecule, which can break down over a thousand cGMP molecules per second.[3] Thus, rods can have a large response to a small amount of light.

As the retinal component of rhodopsin is derived from vitamin A, a deficiency of vitamin A causes a deficit in the pigment needed by rod cells. Consequently, fewer rod cells are able to sufficiently respond in darker conditions, and as the cone cells are poorly adapted for sight in the dark, night-blindness can result.

Reversion to the resting state

[edit]Rods make use of three inhibitory mechanisms (negative feedback mechanisms) to allow a rapid revert to the resting state after a flash of light.

Firstly, there exists a rhodopsin kinase (RK) which would phosphorylate the cytosolic tail of the activated rhodopsin on the multiple serines, partially inhibiting the activation of transducin. Also, an inhibitory protein, arrestin, then binds to the phosphorylated rhodopsins to further inhibit the rhodopsin activity.

While arrestin shuts off rhodopsin, an RGS protein (functioning as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP)) drives the transducin (G-protein) into an "off" state by increasing the rate of hydrolysis of the bonded GTP to GDP.

When the cGMP concentration falls, the previously open cGMP sensitive channels close, leading to a reduction in the influx of calcium ions. The associated decrease in the concentration of calcium ions stimulates the calcium ion-sensitive proteins, which then activate the guanylyl cyclase to replenish the cGMP, rapidly restoring it to its original concentration. This opens the cGMP sensitive channels and causes a depolarization of the plasma membrane.[10]

Desensitization

[edit]When the rods are exposed to a high concentration of photons for a prolonged period, they become desensitized (adapted) to the environment.

As rhodopsin is phosphorylated by rhodopsin kinase (a member of the GPCR kinases (GRKs) ), it binds with high affinity to the arrestin. The bound arrestin can contribute to the desensitization process in at least two ways. First, it prevents the interaction between the G protein and the activated receptor. Second, it serves as an adaptor protein to aid the receptor to the clathrin-dependent endocytosis machinery (to induce receptor-mediated endocytosis).[10]

Sensitivity

[edit]A rod cell is sensitive enough to respond to a single photon of light[11] and is about 100 times more sensitive to a single photon than cones. Since rods require less light to function than cones, they are the primary source of visual information at night (scotopic vision). Cone cells, on the other hand, require tens to hundreds of photons to become activated. Additionally, multiple rod cells converge on a single interneuron, collecting and amplifying the signals. However, this convergence comes at a cost to visual acuity (or image resolution) because the pooled information from multiple cells is less distinct than it would be if the visual system received information from each rod cell individually.

Rod cells also respond more slowly to light than cones and the stimuli they receive are added over roughly 100 milliseconds. While this makes rods more sensitive to smaller amounts of light, it also means that their ability to sense temporal changes, such as quickly changing images, is less accurate than that of cones.[3]

Experiments by George Wald and others showed that rods are most sensitive to wavelengths of light around 498 nm (green-blue), and insensitive to wavelengths longer than about 640 nm (red). This is responsible for the Purkinje effect: as intensity dims at twilight, the rods take over, and before color disappears completely, peak sensitivity of vision shifts towards the rods' peak sensitivity (blue-green).[13]

See also

[edit]List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

References

[edit]- ^ Curcio, C. A.; Sloan, K. R.; et al. (1990). "Human photoreceptor topography". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 292 (4): 497–523. doi:10.1002/cne.902920402. PMID 2324310. S2CID 24649779.

- ^ "The Rods and Cones of the Human Eye". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Kandel E.R., Schwartz, J.H., Jessell, T.M. (2000). Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed., pp. 507–513. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- ^ "Photoreception" McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology, vol. 13, p. 460, 2007

- ^ "How Big Is a Photoreceptor". Cell Biology By The Numbers. Ron Milo & Rob Philips.

- ^ Li, Shuai; Mitchell, Joe; Briggs, Deidrie J.; Young, Jaime K.; Long, Samuel S.; Fuerst, Peter G. (1 March 2016). "Morphological Diversity of the Rod Spherule: A Study of Serially Reconstructed Electron Micrographs". PLOS ONE. 11 (3): e0150024. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1150024L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150024. PMC 4773090. PMID 26930660.

- ^ Human Physiology and Mechanisms of Disease by Arthur C. Guyton (1992) p. 373

- ^ "G Proteins". rcn.com. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ Muradov, Khakim G.; Artemyev, Nikolai O. (10 March 2000). "Loss of the Effector Function in a Transducin-α Mutant Associated with Nougaret Night Blindness". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (10): 6969–6974. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.10.6969. PMID 10702259. Retrieved 25 January 2017 – via www.jbc.org.

- ^ a b Bruce Alberts, Alexander Johnson, Julian Lewis, Martin Raff, Keith Roberts, Peter Walter (2008). Molecular Biology of The Cell, 5th ed., pp.919-921. Garland Science.

- ^ Okawa, Haruhisa; Alapakkam P. Sampath (2007). "Optimization of Single-Photon Response Transmission at the Rod-to-Rod Bipolar Synapse". Physiology. 22 (4). Int. Union Physiol. Sci./Am. Physiol. Soc.: 279–286. doi:10.1152/physiol.00007.2007. PMID 17699881.

- ^ Bowmaker J.K. and Dartnall H.J.A. (1980). "Visual pigments of rods and cones in a human retina". J. Physiol. 298: 501–511. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013097. PMC 1279132. PMID 7359434.

- ^ Wald, George (1937b). "Photo-labile pigments of the chicken retina". Nature. 140 (3543): 545. Bibcode:1937Natur.140..545W. doi:10.1038/140545a0. S2CID 4108275.