Regent's Park College, Oxford

| Regent's Park College | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Oxford | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Arms: Argent on a cross gules an open Bible properly irradiated or the pages inscribed with the words DOMINUS JESUS in letters sable on a chief wavy azure fish or. | ||||||||||||

| Location | Pusey Street | |||||||||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′26″N 1°15′39″W / 51.757255°N 1.260964°W | |||||||||||

| Full name | Regent's Park College, Oxford | |||||||||||

| Latin name | Collegium de Principis Cum Regentis Paradiso | |||||||||||

| Motto | Omnia probate quod bonum tenete (Latin) | |||||||||||

| Established | founded 1752 incorporating an education society in 1810 | |||||||||||

| Named for | Regent's Park, London | |||||||||||

| Previous names | Stepney Academy (to 1856) | |||||||||||

| Sister college | Lucy Cavendish College, Cambridge | |||||||||||

| Principal | Sir Malcolm Evans[1] | |||||||||||

| Grace | see below | |||||||||||

| Website | www | |||||||||||

| Boat club | JCR Website | |||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||

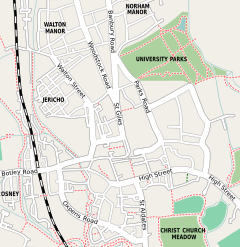

Regent's Park College (known colloquially within the university as Regent's) is a permanent private hall of the University of Oxford, situated in central Oxford, just off St Giles', England, United Kingdom.

Founded in 1810, the college moved to its present site in 1927 and became a licensed hall of the university in 1957. The college now admits both undergraduate and graduate students to take Oxford degrees in a variety of arts, humanities and social science subjects. It is one of the few academic institutions within the University of Oxford to have accepted women as well as men since before the mid-twentieth century, with women attending college since the 1920s. It is affiliated with the Baptist Union of Great Britain.

As of 2022, Regent's Park College had a financial endowment of £7.8 million.[2]

History

[edit]Origins in London

[edit]Regent's Park College traces its roots to the formation of the London Baptist Education Society in 1752.[3] This venture led to the development of the Baptist College, Stepney, a dissenting academy in the East End of London, in 1810. The impetus for the creation of the college arose from the fact that only members of the Church of England were given places at the ancient universities. There were only three students in 1810, but by 1850 the number had risen to 26.[4]

In 1849, Joseph Angus (Principal 1849–1893) became principal at just 33 years old.[5] At the beginning of his time as principal, Angus admitted a small number of lay students to the college. His belief was that it would benefit the ministerial students to have contact with them, as well as bring much-needed finances to the college. After sites in Gordon Square and Primrose Hill were considered, Angus decided on 12 December 1855 to relocate the college to Holford House in the rural environs of Regent's Park and to change its name to ''Regent's Park College''.[6] Holford House was a private dwelling built in the classical Georgian style on Crown land.[7] Students were able to read for university degrees in the arts and law, as well as training for Christian ministry.[citation needed]

After many long ties with University College London, which date back to 1856, the college became an official divinity school of the University of London in 1901. In 1920, George Pearce Gould (1896–1920) passed the role of principal on to Henry Wheeler Robinson, who would hold the post until 1942. Wheeler Robinson was educated at Regent's Park College for one session; he then went to Edinburgh University and finally to Mansfield College, Oxford. Wheeler Robinson believed that Oxford was a more congenial setting than London for a college. This belief, coupled with the lure of the advantages of the tutorial system and the fact that Baptists remained the only Free church without a college in one of the ancient universities, led Wheeler Robinson to decide to relocate the college to Oxford.[8]

Relocation to Oxford

[edit]In 1927, the main portion of the site was purchased and the buildings, including various farm buildings and two wells in Pusey Street, were secured shortly afterwards from St John's College. The college appointed T Harold Hughes (1897–1949) as the architect for the site. Hughes was responsible for much extension and restoration work in Oxford, including Exeter College, Hertford College and Corpus Christi College.[9] The first four students arrived in 1928. At this time, many of the classes were held at Mansfield College and other lectures were held at various other colleges. However, as early as 1924, Wheeler Robinson started to promote his plans for a new building scheme on the Oxford site to former students. Between 1935 and 1938, he and E. A. Payne spoke at various meetings and raised £20,000 of the £50,000 needed for the project.[10] The foundation stones for Helwys Hall were laid on 21 July 1938, by representatives from the Baptist Union of Great Britain and Ireland, the Particular Baptist Fund, and the Baptist Missionary Society. Stones were also laid in memory of Angus and Gould, former principals of the college.[citation needed]

The Main Block, consisting of 16 study bedrooms, Helwys Hall, the College Library, the Senior Common Room and part of the building on Pusey Street, were constructed from 1938 to 1940. However, the outbreak of the Second World War along with a lack of funds meant that the ambitious plans for the completion of the quadrangle had to be put on hold.[11]

In 1957, Regent's Park College became a permanent private hall of the University of Oxford. During this period, the college once again started to accept non-ministerial undergraduates and new buildings on Pusey Street were erected to accommodate the college's growing size, thus completing the quadrangle. The Balding student accommodation block was built in 1960, and a large window was fitted in a three-storey high wall overlooking Balding Quadrangle behind the main quadrangle – allegedly the largest single pane of glass in Europe. In 1977, the Angus student accommodation block was built thus providing Balding Quadrangle with an extra side. Extra accommodation was built in Wheeler Robinson House in 1988. When Greyfriars closed in 2008 (having been a permanent private hall since 1958), the remaining 30 students joined Regent's Park College.[12] When St Bennet's Hall closed in September 2022, 29 of the former Hall's students joined Regent's.[13]

Buildings

[edit]

Regent's Park College is located just off St Giles' in the heart of Oxford, near St Cross College and St John's College. The site is based around a large neoclassical quadrangle (as seen in the adjacent picture). The quadrangle is well known for the extensive Virginia creeper which covers most of the buildings. On the south side of the quad are the college entrance and lodge. On the west side is the Hall, with two Ionic columns flanking the main entrance to the room. The names "Thomas Helwys" and "William Carey" are carved on either side of the glass door leading into the Hall. Thomas Helwys was a religious refugee in Holland and returned to England to start the first Baptist church. William Carey was a missionary to India and inspired the foundation of the Baptist Missionary Society in 1792.[14]

The college also owns seventeenth- and eighteenth-century houses which face out onto St. Giles' as well as more recent developments, such as Wheeler Robinson House, which is used for third-year accommodation, and Gould House and Angus House, both of which are used either for undergraduates or tutors. All undergraduate accommodation is on-site, or less than a three-minute walk away from the main college buildings. The college also makes use of some central University accommodation provisions for postgraduates, notably the Castle Mill development in North Oxford and some houses in Wellington Square. [citation needed]

Helwys Hall

[edit]Helwys Hall is home to a series of portraits which, taken together, present a brief history of the college. Most of the former principals' portraits are displayed including a recent portrait of Professor Paul Fiddes and Dr. Robert Ellis. There are also portraits of Joshua Marshman, Hannah Marshman, William Carey, and Willam Ward who were all missionaries to India and Andrew Fuller who was a missionary and first secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society. Helwys Hall was completely renovated in 2009 with a gift to the college's Annual Fund from an anonymous donor.[citation needed]

Common Rooms

[edit]The Junior Common Room

The JCR is adorned with pictures of Regent's sports teams. The room also has a JCR presidents' board with the name of every JCR president until Rosie Marie Walsh (2021) and a board recording all Regent's students who have received a Blue from the university.

The Middle Common Room

The MCR is the college's Postgraduate community. Hosting a variety of Ministerial, Mature Undergraduate, Master's, Doctoral and Part-time Students.

The Senior Common Room

The SCR, which is used by academic and administrative staff, was provided by a gift from the nieces and nephews of George Pearce Gould (principal 1896–1920). A portrait of Gould hangs over an Adams brothers' mantelpiece. Facing Gould is a portrait of William Kiffin which dates back to 1667.[15]

Libraries

[edit]The College Library

[edit]The College Library is on the third floor of the college above Helwys Hall and houses many key works relating to theology, as well as many works on history, geography and politics. It contains graduate study rooms as well as a number of computers.[citation needed]

In the library, there is a semi-circular window with sixteen panels, on which is etched a map of the world with many interesting symbols and emblems. The window came from the Glasgow Empire Exhibition of 1937 and is a fine example of modern glasswork. The library contains portraits of both William Carey and John Bunyan, and outside it hangs a portrait of Henry Havelock.[citation needed]

Angus Library and Archive

[edit]The Angus Library and Archive is a scholarship library holding volumes and documents on Baptist history and culture. The core of the collection was left to the college by Joseph Angus who was principal from 1849 to 1893. The Angus now comprises over 70,000 printed books, pamphlets, journals, church and association records, church histories, manuscript letters and other artefacts from the late fifteenth century to the present day. The collection relates to the life and history of Baptists in Britain and the wider world. There is a considerable amount of material from non-Baptist sources relating to issues and controversies in which Baptists were involved.[citation needed]

The Angus Library and Archive are used by scholars researching Baptist history, the history of dissent in the UK, and the social history of foreign missions and linguistics. It is also used by members of the public to research family and local history.[16]

Academics

[edit]Students are admitted and matriculated according to the same admissions procedures as the other colleges and halls of the University of Oxford. The college specializes in the arts, humanities and theology.[17] It is affiliated with the Baptist Union of Great Britain.

Student life

[edit]

There are sports teams in football, rowing, netball and basketball as well as opportunities to play other sports for other Oxford colleges. [citation needed]

The Junior Common Room also provides arts activities, such as an annual play and pantomime, as well as several social societies.[18][19]

Each summer, the college hosts a themed ball named The Final Fling. During Trinity Term, croquets and Pimms are enjoyed on the quad, which is also occupied by the college tortoise. The college's first tortoise, Emmanuelle, won the Corpus Christi Tortoise Fair twice,[20] as well as appeared on Blue Peter.[21]

On 3 October 2022, Emanuelle died, after most recently celebrating her supposed 119th birthday (although her age was more likely between 80 and 100 years old).[22] She was immortalised in the college chapel's new stained glass window.[23] On 27 May 2023, the college welcomed a new young tortoise, Truffle.[24]

Traditions

[edit]

Motto

[edit]The college motto is: Omnia probate quod bonum tenete. It is taken from 1 Thessalonians 5:21: "Test all things; hold fast to that which is good" (A.V.)[citation needed]

Grace and Hall

[edit]The college grace is recited in the vernacular by the principal and runs as follows: For the gifts of your grace and the community of this college, we praise your name, O God. Amen. At the end of the Formal Hall, the Senior Common Room depart after the principal has said the words "The grace and peace of God be with us all. Amen".[citation needed]

In the early days of the college at Oxford, there was a Latin grace which was thought to be composed by Aubrey Argyle: Agimus Tibi gratias, Omnipotens Deus, pro his et universis donis Tuis quae de Tua largitate sumus sumturi, Per Jesum Christum, Dominum Nostrum. Amen. This was allegedly swiftly dropped as Henry Wheeler Robinson, then principal, observed a strict 'no-Latin' policy in Hall – in the old days, offenders were thrown into a bath of cold water. It has also traditionally been the case that there is no Loyal Toast at college dinners. Around the turn of the millennium, the dean even remonstrated with guests from a different college to prevent the toast from being proposed.[21]

Unlike many other Oxford colleges, the same menu is served to all members of the college and there is no High Table apart from in formal halls. It also observes a tradition that grace is said at every meal, with students and dons alike standing behind their chairs until it has been said.[citation needed]

Valediction

[edit]The principal ceremonial occasion in the college year is the Service of Valediction, which takes place on the afternoon of the last day of Full Term in Trinity (always a Saturday). The most important part of the ceremony is the signing of the register by members of the Junior and Middle Common Rooms whose periods of study have come to an end. This is different from the practice at other colleges that maintain a register (now a minority of colleges), where the signing takes place at the beginning of a student's course.[citation needed]

Other traditions

[edit]A tradition from the nineteenth century, which is now somewhat forgotten (despite having been common even in the early years of the twenty-first century) was that first-year students of the college are called "monarchs" and their elder colleagues are known as "regents". This was to remind older students that they had a duty of care to the younger members, much as a regent has a duty of care to an infirm monarch (the metaphor appears to have been drawn from the regency of George IV, after whom Regent's Park in London, the college's namesake, is named).[25]

Ernest A. Payne, a former alumnus of the college who attended Regent's during its move to Oxford in the 1920s, mentions in passing during a lecture delivered in the 1970s that there was at one time a college song, which was sung as the students vacated the premises in Regent's Park. The chorus of the song was cited by Payne to have been as follows:

So we raise, as time goes by,

Our Marseillaise, our battle-cry,

Forward Regent's!"

People associated with Regent's Park College

[edit]Principals

[edit]Alumni

[edit]

- William Abraham, Irish theologian, Professor of Wesley Studies, Southern Methodist University

- Joseph Angus, Biblical scholar, Principal of (Stepney Academy and) Regent's Park College (1849–93)

- Robin Attfield, Professor of Philosophy at Cardiff University

- Simon Bailey, Anglican priest and author

- Malcolm Bishop, QC, judge and barrister

- William Brock, abolitionist, biographer, and supporter of missionary societies

- T Davis Bunn, a novelist in residence

- Wayne Clarke, radio presenter, producer, and author

- Robert Ellis Principal (2007–2021) and Senior Research Fellow of Regent's Park College [27]

- Sir Malcolm Evans, KCMG, OBE, FLSW, academic and Principal of Regent's Park College from 2023

- Paul Fiddes, FBA, Professor of Systematic Theology, Principal (1989–2007) and Senior Research Fellow of Regent's Park College, and honorary Fellow of St Peter's College

- James Gandhi, child actor and writer from the BBC children's show Dani's House

- Sir Henry Havelock, KCB, British general instrumental in the Indian Rebellion of 1857

- Donald Foster Hudson, Baptist missionary and author

- Jesse Jackson, an honorary Fellow of the college[28]

- Delyth Jewell, assembly member for South East Wales

- R T Kendall, writer and minister (1977–2002) of Westminster Chapel

- Alexandra Knatchbull, descendant of Queen Victoria and god-daughter of Diana, Princess of Wales

- Alan Kreider, former professor of Church History and Mission, Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, Indiana

- Richard Land, President of Southern Evangelical Seminary, North Carolina

- Alexander Larman, author and journalist

- Sir Joseph Leese, 1st Baronet, KC, first-class cricketer, British lawyer, and Liberal politician

- Walter John Mathams, hymn-writer and founder of the Ladies Guild of the Sailors' Society

- Frederick Brotherton Meyer, Baptist minister and evangelist, writer, and moral reformer

- Gregory Norminton, novelist

- Wesley Pue, former professor of Legal History at University of British Columbia

- Ian Randall, FRHistS, British historian

- Keith Riglin, former Vice Dean of King's College London, Bishop of Argyll and The Isles

- Henry Wheeler Robinson, Old Testament scholar, Principal of Regent's Park College (1920–42)

- Olin Robison, diplomat, thirteenth President of Middlebury College, Vermont

- William Rouse, Classical scholar and educational reformer, former headmaster of The Perse School, Cambridge

- Roland Rudd, PR and business consultant, founder and chairman of Finsbury

- David Russell, CBE, former Principal of Rawdon College, former General Secretary, Baptist Union of Great Britain

- Philip Ryken, eighth President of Wheaton College, Illinois

- Jane Shaw, former Dean of Divinity, New College, Oxford, Principal, Harris Manchester College, Oxford

- Cecil Staton, eleventh Chancellor of East Carolina University, North Carolina

- James Sully, philosopher and psychologist

- Michael Symmons Roberts, poet

- Alfred Thomas, 1st Baron Pontypridd, DL, politician and Welsh nationalist

- Andrew Thompson, CBE, Professor of Global and Imperial History, University of Oxford

- Barnaby Thompson, film director and producer

- Michael Ward, author of Planet Narnia, Professor of Apologetics, Houston Baptist University, Texas

- Robert Warner, Vice Chancellor, Plymouth Marjon University

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Regent's Park College welcomes its new Principal". Regent’s Park College, Oxford. 4 January 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ "Regent's Park College Report of the trustees for the year ended 31 August 2022". register-of-charities.charitycommission.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "THE Pre-history of Regent's Park College" (PDF). biblicalstudies.org.uk. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Gould, 1910, 1

- ^ Gould, 1910, p. 56

- ^ Gould, 1910, p. 58

- ^ Cooper, 1960, p. 61

- ^ Gould, 1910, p. 84

- ^ The Dictionary of Scottish Architects, 2010.

- ^ Cooper, 1960, p. 89

- ^ Cooper, 1960, p. 120

- ^ "Closure of Greyfriars: University Statement - University of Oxford". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ https://gazette.web.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/gazette/documents/media/10_november_2022_-_no_5365_redacted.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ William Carey Society, 2010

- ^ Kreitzer and Rooke, 2006

- ^ "Regent's Park College | Regent's Park College". Rpc.ox.ac.uk. 12 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Regent's Park College, ABOUT REGENT’S, rpc.ox.ac.uk, UK, retrieved May 5, 2023

- ^ "Clubs and Societies | Regent's Park College JCR". www.regentsjcr.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "JCR | Regent's Park College JCR". Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ "President's Welcome | Regent's Park College JCR". Archived from the original on 17 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ a b [1] Archived 11 April 2013 at archive.today

- ^ Floate, Fiona (3 October 2022). "We are very sad to announce that Emmanuelle, the College's much loved tortoise, has died". Regent's Park College.

- ^ "Oxford college's 'most important resident' tortoise dies". BBC News. 5 October 2022.

- ^ "Truffle's Welcome Party! tickets on Saturday 27 May | Regent's Park College JCR Charities Representative". FIXR. Regent's Park College JCR Charities Representative.

- ^ Robert E. Cooper, From Stepney to St Giles': the Story of Regent's Park College, 1810–1960, page 25

- ^ "Regent's Park College, Oxford" (PDF). Biblicalstudies.org.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ "New Principal sought for the College". Regent's Park College, Oxford. 31 March 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "UK | England | Oxfordshire | Black youngsters 'key to Oxford'". BBC News. 14 November 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Anthony Clarke and Paul Fiddes, Dissenting Spirit: A History of Regent's Park College, 1752-2017 (Oxford: Centre for Baptist History and Heritage, 2017) (336 pages, illustrated)

- Robert E. Cooper, From Stepney to St Giles': the Story of Regent's Park College, 1810–1960 (London: Carey Kingsgate Press, 1960) (148 pages, illustrated)

- Geo. P. Gould, The Baptist College at Regent's Park (Founded at Stepney 1810): A Centenary Record (London: The Kingsgate Press, 1910) (99 pages, illustrated)

External links

[edit]- Regent's Park College, Oxford

- Baptist universities and colleges in the United Kingdom

- Bible colleges, seminaries and theological colleges in England

- Buildings and structures of the University of Oxford

- Educational institutions established in 1810

- Educational institutions established in 1752

- Permanent private halls of the University of Oxford

- Former colleges of the University of London

- 1810 establishments in England

- 1752 establishments in England

- Universities and colleges established in the 18th century