Llívia

Llívia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 42°27′52″N 1°58′51″E / 42.46444°N 1.98083°E | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous community | |

| Province | Girona |

| Comarca | Cerdanya |

| Judicial district | Puigcerdà |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Albert Cruïlles Ruaix (2024)[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 12.9 km2 (5.0 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,224 m (4,016 ft) |

| Population (2018)[3] | |

• Total | 1,428 |

| • Density | 110/km2 (290/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | Llivienc, llivienca (ca) Lliviense (es) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 17527 |

| Website | www |

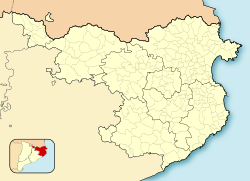

Llívia (Catalan pronunciation: [ˈʎiβiə]; Spanish: Llivia Spanish: [ˈʎiβja] ) is a town in the comarca of Cerdanya, province of Girona, Catalonia, Spain. It is a Spanish exclave surrounded by the French département of Pyrénées-Orientales.[4]

In 2023, the municipality of Llívia had a total population of 1,511.[5] It is separated from the rest of Spain by a corridor about 1.6 km (1.0 mile) wide, which includes the French communes of Ur and Bourg-Madame. The Segre river, a tributary of the Spanish Ebro, flows through Llívia.

History

[edit]

Llívia was the site of an Iberian oppidum that commanded the region and was named Julia Lybica[6] by the Romans. It was the capital of Cerdanya in antiquity, before being replaced by Hix (commune of Bourg-Madame, France) in the Middle Ages. During the Visigothic period, its citadel, the castrum Libiae, was held by the rebel Paul of Narbonne against King Wamba in 672. As the "town (or 'city') of Cerdanya," 8th century Llívia may also have been the scene of the siege by which governor Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi of Muslim Spain rid himself of the Moorish (Berber) rebel Uthman ibn Naissa ("Munnuza"), who had allied himself with Duke Eudo of Aquitaine to improve the chances of his rebellion,[7] ahead of the Battle of Tours (732 or 733), also known as the Battle of Poitiers.

Following the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659), the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659 ceded the comarques of Roussillon, Conflent, Capcir, Vallespir, and northern Cerdanya ("Cerdagne") to the French Crown. The treaty thus established the Pyrenees as the border between France and Spain, while separating Northern Catalonia from Catalonia. However, the treaty stipulated that only villages were to be ceded to France, and Llívia was considered a town (vila in Catalan), since it had the status of the ancient capital of Cerdanya.[8] So Llívia remained a Spanish enclave within France and did not become part of the Kingdom of France. This situation was confirmed in the subsequent Treaty of Llívia, signed in 1660.[9]

Under the Nationalist government of Francisco Franco, residents required special passes to cross France to the rest of Spain. Today, with these countries in the Schengen Area, there are no frontier formalities and cross-border infrastructure is the only issue.[10] The two countries share a hospital in Llívia, as well as other local initiatives.[11]

The enclave is accessible from Spain via a 1.8 km (1 mile) long road that up until the implementation of the Schengen Area in 1995 was considered a "neutral road" as defined in the Treaty of Llívia. The road was designated as being a custom-free route across which the French were allowed free access from one part of the corridor to another and for the Spanish to travel freely between Puigcerdà and Llívia.[9] This road is the joint property of Spain and France and is designated in Spain as part of the N-154 and in France as jointly part of the Route nationale 20 and the RD68. The road has been the subject of controversy over the years, particularly due to a number of stop signs placed by the French authorities and removed overnight by those opposed to them. This lasted for several years and became known as the war of the stop signs.[12]

During the vote for Catalan independence in 2017, 561 out of 591 votes cast in Llívia were in favor of independence. The referendum was deemed illegal by the Spanish courts, but the Spanish police did not intervene to stop the vote in the town.[13]

Museum

[edit]

The Esteve Pharmacy, located in Llívia's municipal museum, is a complete 18th-century pharmacy donated to the town by the family who owned it, on condition the contents remain in the town. There are records of pharmacists practising in Llívia since medieval times. The pharmacy has a large display of albarelli, a type of ceramic jar used in pharmacies, as well as antique drugs, and one of the most important collections of prescription books in Europe.[14]

Education

[edit]

Escola Jaume I is located in Llívia.[15] It was built in the 1950s. As of 2016[update] a new school was constructed with a 500 m2 (5,400 sq ft) ground floor and a 250 m2 (2,700 sq ft) second floor.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ "Ajuntament de Llívia". Ajuntament de Llívia. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ "El municipi en xifres: Llívia". Statistical Institute of Catalonia. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ Robinson GWS (1959). Exclaves. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 49 (3), 283–295 doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1959.tb01614.x

- ^ Idescat. Fitxes municipals. Llívia

- ^ Merino, Antolin; de la Canal, José (1819). "De la santa iglesia de Gerona" (in Catalan). Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Auctores Antiquissimi, p. 361, and Roger Collins, The Arab Conquest of Spain, 710–797, Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 1989, p. 89

- ^ Capdevila i Subirana, Joan: Historia del deslinde de la frontera Hispano-Francesa. Del tratado de los Pirineos (1659) a los tratados de Bayona (1856–1868), Ed. Ministerio de Fomento, Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica, Madrid, 2009, pp. 146–149. ISBN 978-84-416-1480-2 (Spanish)

- ^ a b "Treaty on boundaries between Spain and France from the valley of Andorra to the Mediterranean (with additional act). Signed at Bayonne on 26 May 1866 Final Act approving annexes and regulations relating to the above-mentioned Treaty. Signed at Bayonne on 11 July 1868" (PDF). United Nations. 21 September 1982. p. 6. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Nogueira Calvar, Andrea (4 September 2014). "The Spanish town that ended up in France". El País.

- ^ Wilkinson, Isambard (2 January 2003). "Spanish enclave breaks down the barriers with France". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Llivia, l'enclave catalane qui empêche les ronds-points de tourner en rond". ladepeche.fr (in French). Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Fourquet, Laure (24 October 2017). "This Catalan Town Has Already Broken From Spain, Physically at Least". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2017. – Version in Castillian Spanish

- ^ Panareda Clopés, Josep Maria; Rios Calvet, Jaume; Rabella Vives, Josep Maria (1989). Guia de Catalunya, Barcelona: Caixa de Catalunya. ISBN 84-87135-01-3 (Spanish). ISBN 84-87135-02-1 (Catalan).

- ^ Home. Escola Jaume I. Retrieved on December 3, 2017.

- ^ "Llívia es construirà la seva nova escola i després la llogarà a Ensenyament". Diari de Girona. 10 February 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

L'actual centre educatiu del municipi, Jaume I, es va construir fa més de 60 anys,[...]El nou centre escolar de Llívia serà un edifici a dues aigües amb una planta de 500 metres quadrats i un segon pis de 250 metres.

External links

[edit] Media related to Llívia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Llívia at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Government data pages (in Catalan)