Undershaw

| Undershaw | |

|---|---|

The façade of Undershaw, circa 1900, with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's children Mary and Kingsley on the driveway | |

| Location | Hindhead |

| Coordinates | 51°06′48″N 0°44′00″W / 51.113252°N 0.733412°W |

| OS grid reference | SU8875735647 |

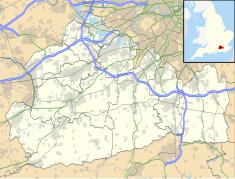

| Area | Surrey |

| Built | 1897 |

| Architect | Joseph Henry Ball |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Undershaw |

| Designated | 19 September 1977 |

| Reference no. | 1244471 |

Undershaw is a former residence of the author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes. The house was built for Doyle at his order to accommodate his wife's health requirements, and is where he lived with his family from 1897 to 1907. Undershaw is where Doyle wrote many of his works, including The Hound of the Baskervilles.

For decades after Doyle sold the house, Undershaw served as a hotel, which closed in 2004. The property was then vacant, and the subject of controversy. In 2014 the house and grounds were purchased by the DFN Charitable Foundation for Stepping Stones School, a school for children with special needs.

Location

Undershaw is located close to the A333 road in the village of Hindhead in Surrey, near the town of Haslemere and is about 40 miles (64 km) south west of London. The name refers to the sheltering flora; 'shaw' is an Anglo-Saxon word that means 'a nearby grove of hanging trees'.[1] The house is situated with a view of an undeveloped valley extending to the South Downs.[2]

The location was chosen to cater to the medical needs of Doyle's wife Louise, nicknamed 'Touie', who had tuberculosis; doctors of the era recommended healthy air, for which Surrey was known. Writing to his mother Mary in May 1895, Doyle lauded the building site because "... its height, its dryness, its sandy soil, its fir trees, and its shelter from all bitter winds present the conditions which all agree to be best in the treatment of phthisis. If we could have ordered Nature to construct a spot for us we could not have hit upon anything more perfect. ... I have bought 4 acres under £1000 and I don't think it will prove to be a bad investment."

In the same letter Doyle extolled the pleasures and convenience of the location. "As to my own amusements there I am within an hour of town and an hour from Portsmouth. I have golf, good cricket, my own billiard table, excellent society, a large lake to fish in not far off, riding if I choose to take it up, and some of the most splendid walks & scenery that could be possibly conceived."[3]

Construction and style

[Dracula creator] Bram Stoker, who visited in 1907, found the house "cozy and snug to a remarkable degree", and added that the many curios and artworks created an effect like a "fairy pleasure house." ...

"For Conan Doyle, who had spent his childhood bouncing from one flat to another in Edinburgh, Undershaw brought a welcome stability. His own children, after the upheavals of the previous four years, now had a beautiful home and four acres of wooded land to explore."

— from The Teller of Tales by Arthur Conan Doyle biographer Daniel Stashower[1]Doyle commissioned the construction on the site by architect Joseph Henry Ball, whom Doyle described as "...an old friend and a man of most fastidious taste and critical turn of mind who will keep a constant eye upon the work."[3] Built in the style 'Surrey-vernacular', the house is largely composed of red brick and is asymmetrical. A factor in the construction was the large south-facing windows, which let in plentiful light, intended to provide a cheerful indoor environment. The windows also featured specially manufactured stained glass with a coat of arms said to be that of Doyle's family; many of these have not survived the attacks of vandals in recent years.

Undershaw's main entrance opened into an entry hall of two stories with a brick fireplace. Doyle's home also included a generator for the electric lighting, which was not common outside of cities at the time, and a dining room which could seat thirty people. A special display shelf in the wood-panelled drawing room, located near the ceiling, displayed a collection of weapons, stuffed birds, walrus tusks and various trophies.[1] The doors of the house were also unusual in that they open both ways. The current internal layout has 14 bedrooms, with a size of 10,000 square feet (930 m2).[2]

Doyle's three-storey home featured a grand staircase of shallow steps, to prevent Louise Doyle from becoming winded on the way upstairs. It also boasted a billiards room and Doyle's private book-lined study, where the author wrote some of his best-known work.[4]

History

Doyle lived at Undershaw for a decade between 1897 and 1907 (Louise died in 1906).[5] The house was the place where many of Doyle's most famous works were written including The Great Boer War, The Hound of the Baskervilles, The Adventures of Gerard, The Return of Sherlock Holmes, and Sir Nigel.[6]

Doyle also entertained many notable house guests at Undershaw. These included Sherlock Holmes illustrator Sidney Paget, the famous Sherlock Holmes actor William Gillette, and the author of Dracula, Bram Stoker. Other notable visitors included E.W. Hornung, J.M. Barrie, Thomas Wemyss Reid, Gordon Guggisberg, Churton Collins, Virginia Woolf, and Bertram Fletcher Robinson.[5]

Redevelopment controversy

Undershaw was converted into a hotel not long after Doyle sold it. During 2004, the hotel closed and the property was purchased by Fossway Limited but remained unoccupied.[7]

In June, 2010 the Waverley Borough Council declined to buy Undershaw. The council's chief of planning, Matthew Evans, stated "We don't have that kind of money. We have to tighten our belts." But councillor Jim Edwards, the only vote against the planning officers’ recommendations, stated "This house has got tremendous historical importance. This is a massive development, and quite unacceptable in my view." And Doyle's great-nephew Richard Doyle, reportedly 'upset', said "The family had been trying to come up with ways of buying it, but the price was so high we could not afford it. We just wish there was something we could do."[8]

"This is a place which is steeped in history and should be treated with reverence. Conan Doyle's life and works are a fundamental part of British culture and arguably their stock has never been higher. We have been absolutely delighted to see enthusiasts from across the world get in touch and pledge their support to our efforts."

"We are very hopeful that this decision will signal a sea change in attitude towards this historic property and that it will lead to it being rightly preserved as a single building – hopefully as a museum or centre where future generations can be inspired by the many stories which have been created within its walls.."[9]

— Undershaw Preservation Trust Co-founder John Gibson, regarding the legal decision that halted redevelopment plans for Undershaw in 2012.On 18 August 2010 the Los Angeles Times reported[4] that plans were in motion to redevelop the home into a multi-unit apartment building, stating "The hammers start raining blows on Undershaw as early as next month." The plan continued to be opposed by the preservationists, who wanted to see the house maintained as a single structure in whatever form it is subsequently put to, such as a home or museum. They had been frustrated when attempts to promote Undershaw into the top rank of protected buildings failed.[10][11][12] A government report stated that the house was not architecturally notable, and that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was not of the same standing as Jane Austen or Charles Dickens.[4]

During December 2010, the Undershaw Preservation Trust instigated judicial review proceedings at the High Court of Justice, in an attempt to overturn the decision by Waverley Borough Council to permit the conversion of Undershaw into flats.[13][14][15][16] On 30 May 2012, the High Court voided (also termed "quashed") the Waverley Council's allowance of redevelopment of Undershaw due to legal flaws. Undershaw Preservation Trust co-founder John Gibson saluted the decision by The Hon. Mr Justice Cranston. Others publicly opposing the development plans were Julian Barnes who set part of his novel Arthur & George at Undershaw, former Culture Secretary Jeremy Hunt, and Mark Gatiss, a writer and co-producer of the UK television series Sherlock.[9]

In 2014 the house and grounds were purchased by the DFN Charitable Foundation for Stepping Stones School, to be restored for use as a school for children with hemiplegia, physical, medical, anxiety, and autistic spectrum difficulties. The DFN Foundation stated:

We are totally committed to the restoration of this building to its unique status as the cradle of so much of Conan Doyle’s genius. Our restoration plans encompass all of the original buildings, including the stable block. The features which made Undershaw special, specifically the stained glass windows and our proposal to faithfully re-create Conan-Doyle’s study is very exciting and will be enjoyed by our children and visitors. We very much hope the local community and Conan Doyle enthusiasts from around the world will join us in visiting Undershaw and use some of the facilities which will be created.[citation needed]

The DFN Foundation was established in 2014 by David Forbes-Nixon, and aims to support the areas of education, healthcare and conservation. The Foundation's revised plans for the house's conversion have been supported by the Undershaw Preservation Trust.[17] The school opened in September 2016 after a full restoration of the house and the building of a contemporary extension and annexe.[18]

References

- ^ a b c Stashower, Daniel (1999). Teller of Tales: the life of Arthur Conan Doyle. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 199. ISBN 0-8050-5074-4.

- ^ a b McKay, Sinclair (20 October 2007). "Undershaw: What's to become of it, Watson?". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 6 July 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ a b Lellenberg, Jon; Daniel Stashower; Charles Foley (2007). Arthur Conan Doyle: a life in letters. New York: The Penguin Press. p. 353. ISBN 978-1-59420-135-6.

- ^ a b c Chu, Henry (18 August 2010). "Sherlock Holmes (fans) and the case of the empty house". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ a b "The Haslemere Society: Undershaw". Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ Duncan, Alistair (15 December 2016). An Entirely New Country: Arthur Conan Doyle, Undershaw and the Resurrection of Sherlock Holmes. ISBN 9781908218209. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Sir Arthur Conan Doyle house development appeal upheld". BBC News. BBC News. 12 November 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ "Conan-Doyle descendants upset at Undershaw plan". 9 June 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ a b Meikle, James (30 May 2012). "Conan Doyle's home saved from redevelopment". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Conan Doyle and the barbarians" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Times, 29 July 2010, "Conan Doyle campaigners fight to save the house of the Baskervilles" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Times, 29 July 2010

- ^ "Pressure on Hunt's department to save Conan Doyle's home"[permanent dead link] Haslemere Herald, 6 August 2010

- ^ "Conan Doyles in call to minister over Undershaw" Archived 13 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 2 August 2010

- ^ "Conan Doyle supporters take Undershaw fight to court" Archived 21 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 16 December 2010

- ^ "Sherlock Holmes fans stage last-ditch attempt to save Conan Doyle's home" Archived 22 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Telegraph, 16 December 2010

- ^ "Battle is on to save the house that Conan Doyle built" Archived 30 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Independent, 17 December 2010

- ^ "Campaign against development of Conan Doyle's Undershaw" Archived 12 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine BBC, 13 May 2011

- ^ "Deal struck over Conan Doyle house school plan". BBC News. BBC News. 20 October 2014. Archived from the original on 12 December 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "DFN Home Page". Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

External links

- The Undershaw Preservation Trust.

- DFN Foundation - Undershaw Saved Archived 24 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.