Milky Way: Difference between revisions

Revert vandalism |

→Discovery: elaborated on Avempace |

||

| Line 417: | Line 417: | ||

[[Image:Pic iroberts1.jpg|thumb|Photograph of the "Great Andromeda Nebula" from 1899, later identified as the [[Andromeda Galaxy]].]] |

[[Image:Pic iroberts1.jpg|thumb|Photograph of the "Great Andromeda Nebula" from 1899, later identified as the [[Andromeda Galaxy]].]] |

||

As [[Aristotle]] (384-322 BC) informs us in ''[[Meteorologica]]'' (DK 59 A80), the [[Greek philosophy|Greek philosophers]] [[Anaxagoras]] (ca. 500–428 BC) and [[Democritus]] (450–370 BC) proposed the Milky Way might consist of distant [[star]]s. However, Aristotle himself believed the Milky Way to be caused by "the ignition of the fiery exhalation of some stars which were large, numerous and close together" and that the "ignition takes place in the upper part of the [[atmosphere]], in the [[Sublunary sphere|region of the world which is continuous with the heavenly motions]]."<ref name=Montada>{{cite web|author=Josep Puig Montada|title=Ibn Bajja|publisher=[[Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]]|url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ibn-bajja|date=September 28, 2007|accessdate=2008-07-11}}</ref> The [[ |

As [[Aristotle]] (384-322 BC) informs us in ''[[Meteorologica]]'' (DK 59 A80), the [[Greek philosophy|Greek philosophers]] [[Anaxagoras]] (ca. 500–428 BC) and [[Democritus]] (450–370 BC) proposed the Milky Way might consist of distant [[star]]s. However, Aristotle himself believed the Milky Way to be caused by "the ignition of the fiery exhalation of some stars which were large, numerous and close together" and that the "ignition takes place in the upper part of the [[atmosphere]], in the [[Sublunary sphere|region of the world which is continuous with the heavenly motions]]."<ref name=Montada>{{cite web|author=Josep Puig Montada|title=Ibn Bajja|publisher=[[Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]]|url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ibn-bajja|date=September 28, 2007|accessdate=2008-07-11}}</ref> The [[Astronomy in medieval Islam|Arabian astronomer]], [[Ibn al-Haytham|Alhazen]] (965-1037 AD), refuted this by making the first attempt at observing and measuring the Milky Way's [[parallax]],<ref>{{citation|title=Great Muslim Mathematicians|first=Mohaini|last=Mohamed|year=2000|publisher=Penerbit UTM|isbn=9835201579|pages=49–50}}</ref> and he thus "determined that because the Milky Way had no parallax, it was very remote from the [[earth]] and did not belong to the atmosphere."<ref>{{cite web|title=Popularisation of Optical Phenomena: Establishing the First Ibn Al-Haytham Workshop on Photography|author=Hamid-Eddine Bouali, Mourad Zghal, Zohra Ben Lakhdar|publisher=The Education and Training in Optics and Photonics Conference|year=2005|url=http://spie.org/etop/ETOP2005_080.pdf|accessdate=2008-07-08|format=PDF}}</ref> |

||

The [[ |

The [[Persian people|Persian]] astronomer [[Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī]] (973-1048) proposed the Milky Way [[galaxy]] to be a collection of countless [[Nebula|nebulous]] stars.<ref>{{MacTutor Biography|id=Al-Biruni|title=Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni}}</ref> The [[Al-Andalus|Andalusian]] astronomer [[Ibn Bajjah|Avempace]] (d. 1138) proposed the Milky Way to be made up of many stars but appears to be a continuous image due to the effect of [[refraction]] in the [[Earth's atmosphere]], citing his observation of the [[Conjunction (astronomy and astrology)|conjunction]] of Jupiter and Mars on 500 [[Islamic calendar|AH]] (1106/1107 AD) as evidence.<ref name=Montada/> [[Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya]] (1292-1350) proposed the Milky Way galaxy to be "a myriad of tiny stars packed together in the sphere of the fixed stars" and that that these stars are larger than [[planet]]s.<ref name=Livingston>{{citation|title=Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah: A Fourteenth Century Defense against Astrological Divination and Alchemical Transmutation|first=John W.|last=Livingston|journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society|volume=91|issue=1|date=1971|pages=96–103 [99]|doi=10.2307/600445}}</ref> |

||

Actual proof of the Milky Way consisting of many stars came in 1610 when [[Galileo Galilei]] used a [[Optical telescope|telescope]] to study the Milky Way and discovered that it was composed of a huge number of faint stars.<ref>{{cite web | author= O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. |month = November | year = 2002 | url = http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Galileo.html | title = Galileo Galilei | publisher = University of St Andrews | accessdate = 2007-01-08 }}</ref> In a treatise in 1755, [[Immanuel Kant]], drawing on earlier work by [[Thomas Wright (astronomer)|Thomas Wright]], speculated (correctly) that the Milky Way might be a rotating body of a huge number of stars, held together by [[gravitation|gravitational forces]] akin to the Solar System but on much larger scales. The resulting disk of stars would be seen as a band on the sky from our perspective inside the disk. Kant also conjectured that some of the [[nebula]]e visible in the night sky might be separate "galaxies" themselves, similar to our own.<ref name="our_galaxy">{{cite web | last = Evans | first = J. C. |date= November 24 1998 | url = http://physics.gmu.edu/~jevans/astr103/CourseNotes/ECText/ch20_txt.htm | title = Our Galaxy | publisher = George Mason University | accessdate = 2007-01-04 }}</ref> |

Actual proof of the Milky Way consisting of many stars came in 1610 when [[Galileo Galilei]] used a [[Optical telescope|telescope]] to study the Milky Way and discovered that it was composed of a huge number of faint stars.<ref>{{cite web | author= O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. |month = November | year = 2002 | url = http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Galileo.html | title = Galileo Galilei | publisher = University of St Andrews | accessdate = 2007-01-08 }}</ref> In a treatise in 1755, [[Immanuel Kant]], drawing on earlier work by [[Thomas Wright (astronomer)|Thomas Wright]], speculated (correctly) that the Milky Way might be a rotating body of a huge number of stars, held together by [[gravitation|gravitational forces]] akin to the Solar System but on much larger scales. The resulting disk of stars would be seen as a band on the sky from our perspective inside the disk. Kant also conjectured that some of the [[nebula]]e visible in the night sky might be separate "galaxies" themselves, similar to our own.<ref name="our_galaxy">{{cite web | last = Evans | first = J. C. |date= November 24 1998 | url = http://physics.gmu.edu/~jevans/astr103/CourseNotes/ECText/ch20_txt.htm | title = Our Galaxy | publisher = George Mason University | accessdate = 2007-01-04 }}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:51, 3 March 2010

Infrared image of the core of the Milky Way Galaxy | |

| Observation data | |

|---|---|

| Type | SBbc (barred spiral galaxy) |

| Diameter | 100,000 light years[1] |

| Thickness | 1,000 light years[1] |

| Number of stars | 100-400 billion (1–4×1011) [2] [3] [4] |

| Oldest known star | 13.2 billion years[5] |

| Mass | 5.8×1011 M☉ |

| Sun's distance to galactic center | 26,000 ± 1,400 light-years[citation needed] |

| Sun's galactic rotation period | 220 million years (negative rotation)[citation needed] |

| Spiral pattern rotation period | 50 million years[6] |

| Bar pattern rotation period | 15 to 18 million years[6] |

| Speed relative to CMB rest frame | 552 km/s[7] |

| See also: Galaxy, List of galaxies | |

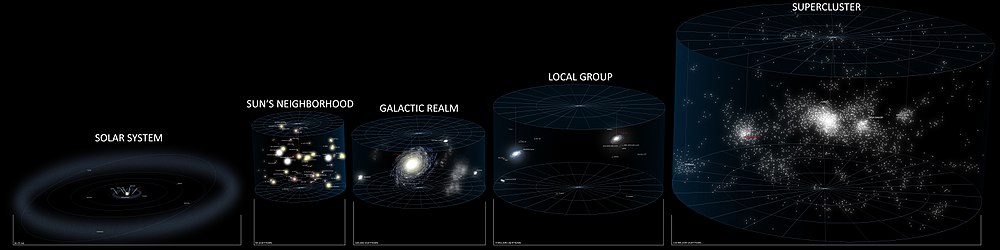

The Milky Way, or simply the Galaxy, is the galaxy in which the Solar System is located. It is a barred spiral galaxy that is part of the Local Group of galaxies. It is one of billions of galaxies in the observable universe. Its name is a translation of the Latin Via Lactea, in turn translated from the Greek Γαλαξίας (Galaxias), referring to the pale band of light formed by stars in the galactic plane as seen from Earth (see etymology of galaxy). Some sources hold that, strictly speaking, the term Milky Way should refer exclusively to the band of light that the galaxy forms in the night sky, while the galaxy should receive the full name Milky Way Galaxy, or alternatively the Galaxy.[8][9][10] However, it is unclear how widespread this convention is, and the term Milky Way is routinely used in either context.

Appearance from Earth

The Milky Way Galaxy, as viewed from Earth's position in a spur of one of the galaxy's spiral arms (see Sun's location and neighborhood), appears as a hazy band of white light in the night sky arching across the entire celestial sphere. The light originates from stars and other material that lie within the galactic plane. The plane of the Milky Way is inclined by about 60° to the ecliptic (the plane of the Earth's orbit), with the North Galactic Pole situated at right ascension 12h 49m, declination +27.4° (B1950) near beta Comae Berenices. The South Galactic Pole is near alpha Sculptoris.

The center of the galaxy lies in the direction of Sagittarius, and it is here that Milky Way looks brightest. Relative to the celestial equator, it passes as far north as the constellation of Cassiopeia and as far south as the constellation of Crux, indicating the high inclination of Earth's equatorial plane and the plane of the ecliptic relative to the galactic plane. From Sagittarius, the Milky Way appears to pass westward through the constellations of Scorpius, Ara, Norma, Triangulum Australe, Circinus, Centaurus, Musca, Crux, Carina, Vela, Puppis, Canis Major, Monoceros, Orion & Gemini, Taurus, Auriga, Perseus, Andromeda, Cassiopeia, Cepheus & Lacerta, Cygnus, Vulpecula, Sagitta, Aquila, Ophiuchus, Scutum, and back to Sagittarius. The fact that the Milky Way divides the night sky into two roughly equal hemispheres indicates that the Solar System lies close to the galactic plane. The Milky Way has a relatively low surface brightness due to the interstellar medium that fills the galactic disk, and preventing us from seeing the bright galactic center. It is thus difficult to see from any urban or suburban location suffering from light pollution.

Panoramas

-

360-degree photographic panorama of the galaxy.

-

A panorama of the Milky Way, as seen from Death Valley, 2005.

-

The plane of our Milky Way Galaxy, which we see edge-on from our perspective on Earth, cuts a luminous swath across the image. Credit: ESO/S. Brunier

-

The Milky Way arches across this rare 360-degree panorama of the night sky above the Paranal platform, home of ESO’s Very Large Telescope. The image was made from 37 individual frames with a total exposure time of about 30 minutes, taken in the early morning hours. The Moon is just rising and the zodiacal light shines above it, while the Milky Way stretches across the sky opposite the observatory. Credit: ESO/H. Heyer

Size

The stellar disk of the Milky Way Galaxy is approximately 100,000 light-years (9×1017 km) (6×1017 mi) in diameter, and is considered to be, on average, about 1,000 ly (9×1015 km) thick.[1] It is estimated to contain at least 200 billion stars[11] and possibly up to 400 billion stars,[12] the exact figure depending on the number of very low-mass stars, which is highly uncertain. This can be compared to the one trillion (1012) stars of the neighbouring Andromeda Galaxy.[13] The stellar disc does not have a sharp edge, a radius beyond which there are no stars. Rather, the number of stars drops smoothly with distance from the centre of the Galaxy. Beyond a radius of roughly 40,000 light-years (4×1017 km) the number of stars drops much faster with radius[14], for reasons that are not understood.

Extending beyond the stellar disk is a much thicker disk of gas. Recent observations indicate that the gaseous disk of the Milky Way has a thickness of around 12,000 ly (1×1017 km)—twice the previously accepted value.[15] As a guide to the relative physical scale of the Milky Way, if it were reduced to 10m in diameter, the Solar System, including the hypothesized Oort cloud, would be no more than 0.1mm in width.

The Galactic Halo extends outward, but is limited in size by the orbits of two Milky Way satellites, the Large and the Small Magellanic Clouds, whose perigalacticon is at ~180,000 ly (2×1018 km).[16] At this distance or beyond, the orbits of most halo objects would be disrupted by the Magellanic Clouds, and the objects would likely be ejected from the vicinity of the Milky Way.

Recent measurements by the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) have revealed that the Milky Way is much more massive than some previously thought. The mass of our home galaxy is now considered to be roughly similar to that of our largest local neighbour, the Andromeda Galaxy. By using the VLBA to measure the apparent shift or parallax of far-flung star-forming regions when the Earth is on opposite sides of the Sun, the researchers were able to measure the distance to those regions using fewer assumptions than prior efforts. The newer and more accurate estimate of the galaxy's rotational speed (and in turn the amount of dark matter contained by the galaxy) is about 254 km/s, significantly higher than the widely accepted value of 220 km/s.[17] This in turn implies that the Milky Way has a total mass of approximately 3 trillion solar masses, about 50% more massive than previously thought.[18]

Age

As of 2004, the age of the oldest star in the galaxy yet discovered, HE 1523-0901, is estimated to be about 13.2 billion years, nearly as old as the Universe.[5] This estimate was determined using the UV-Visual Echelle Spectrograph of the Very Large Telescope to measure the beryllium content of two stars in globular cluster NGC 6397.[19][citation needed] The elapsed time between the rise of the first generation of stars in the Milky Way and the first generation of stars in the cluster was deduced to be 200 million to 300 million years. By including the estimated age of the stars in the globular cluster, 13.4 ± 0.8 billion years, the estimated age of the oldest stars in the Milky Way is 13.6 ± 0.8 billion years. The Galactic thin disk is estimated to have been formed between 6.5 and 10.1 billion years ago.

Composition and structure

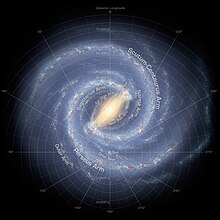

The galaxy consists of a bar-shaped core region surrounded by a disk of gas, dust and stars forming four distinct arm structures spiralling outward in a logarithmic spiral shape (see Spiral arms). The mass distribution within the galaxy closely resembles the Sbc Hubble classification, which is a spiral galaxy with relatively loosely-wound arms.[20] Astronomers first began to suspect that the Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy, rather than an ordinary spiral galaxy, in the 1990s[21]. Their suspicions were confirmed by the Spitzer Space Telescope observations in 2005[22] which showed the galaxy's central bar to be larger than previously suspected.

The Milky Way's mass is thought to be about 5.8×1011 solar masses (M☉)[23][24][25] comprising 200 to 400 billion stars. Its integrated absolute visual magnitude has been estimated to be −20.9. Most of the mass of the galaxy is thought to be dark matter, forming a dark matter halo of an estimated 600–3000 billion M☉ which is spread out relatively uniformly.[25]

Galactic Center

The galactic disc, which bulges outward at the galactic center, has a diameter of between 70,000 and 100,000 light-years.[26] The distance from the Sun to the galactic center is now estimated at 26,000 ± 1400 light-years, while older estimates could put the Sun as far as 35,000 light-years from the central bulge.

The galactic center harbors a compact object of very large mass as determined by the motion of material around the center.[27] The intense radio source named Sagittarius A*, thought to mark the center of the Milky Way, is newly confirmed to be a supermassive black hole. For a photo see Chandra X-ray Observatory; Jan. 6, 2003. Most galaxies are believed to have a supermassive black hole at their center.[28]

The galaxy's bar is thought to be about 27,000 light-years long, running through its center at a 44 ± 10 degree angle to the line between the Sun and the center of the galaxy. It is composed primarily of red stars, believed to be ancient (see red dwarf, red giant). The bar is surrounded by a ring called the "5-kpc ring" that contains a large fraction of the molecular hydrogen present in the galaxy, as well as most of the Milky Way's star formation activity. Viewed from the Andromeda Galaxy, it would be the brightest feature of our own galaxy.[29]

Spiral arms

Each spiral arm describes a logarithmic spiral (as do the arms of all spiral galaxies) with a pitch of approximately 12 degrees. Until recently, there were believed to be four major spiral arms which all start near the galaxy's center. These are named as follows, according to the image at right:

| Color | Arm(s) |

|---|---|

| cyan | 3-kpc and Perseus Arm |

| purple | Norma and Outer arm (Along with a newly discovered extension) |

| green | Scutum-Crux Arm |

| pink | Carina and Sagittarius Arm |

| There are at least two smaller arms or spurs, including: | |

| orange | Orion-Cygnus arm (which contains the Sun and Solar System) |

Observations presented in 2008 by Robert Benjamin of the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater suggest that the Milky Way possesses only two major stellar arms: the Perseus arm and the Scutum-Centaurus arm. The rest of the arms are minor or adjunct arms.[30] This would mean that the Milky Way is similar in appearance to NGC 1365.

Outside of the major spiral arms is the Monoceros Ring (or Outer Ring), proposed by astronomers Brian Yanny and Heidi Jo Newberg, a ring of gas and stars torn from other galaxies billions of years ago.

As is typical for many galaxies, the distribution of mass in the Milky Way Galaxy is such that the orbital speed of most stars in the galaxy does not depend strongly on its distance from the center. Away from the central bulge or outer rim, the typical stellar velocity is between 210 and 240 km/s.[31] Hence the orbital period of the typical star is directly proportional only to the length of the path traveled. This is unlike the situation within the Solar System, where two-body gravitational dynamics dominate and different orbits are expected to have significantly different velocities associated with them. This difference is one of the major pieces of evidence for the existence of dark matter. Another interesting aspect is the so-called "wind-up problem" of the spiral arms. If the inner parts of the arms rotate faster than the outer part, then the galaxy will wind up so much that the spiral structure will be thinned out. But this is not what is observed in spiral galaxies; instead, astronomers propose that the spiral pattern is a density wave emanating from the galactic center. This can be likened to a moving traffic jam on a highway — the cars are all moving, but there is always a region of slow-moving cars. This model also agrees with enhanced star formation in or near spiral arms; the compressional waves increase the density of molecular hydrogen and protostars form as a result.

Halo

The galactic disk is surrounded by a spheroid halo of old stars and globular clusters, of which 90% lie within 100,000 light-years,[32] suggesting a stellar halo diameter of 200,000 light-years. However, a few globular clusters have been found farther, such as PAL 4 and AM1 at more than 200,000 light-years away from the galactic center. While the disk contains gas and dust which obscure the view in some wavelengths, the spheroid component does not. Active star formation takes place in the disk (especially in the spiral arms, which represent areas of high density), but not in the halo. Open clusters also occur primarily in the disk.

Recent discoveries have added dimension to the knowledge of the Milky Way's structure. With the discovery that the disc of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) extends much further than previously thought,[33] the possibility of the disk of our own galaxy extending further is apparent, and this is supported by evidence of the newly discovered Outer Arm extension of the Cygnus Arm.[34] With the discovery of the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy came the discovery of a ribbon of galactic debris as the polar orbit of the dwarf and its interaction with the Milky Way tears it apart. Similarly, with the discovery of the Canis Major Dwarf Galaxy, it was found that a ring of galactic debris from its interaction with the Milky Way encircles the galactic disk.

On January 9, 2006, Mario Jurić and others of Princeton University announced that the Sloan Digital Sky Survey of the northern sky found a huge and diffuse structure (spread out across an area around 5,000 times the size of a full moon) within the Milky Way that does not seem to fit within current models. The collection of stars rises close to perpendicular to the plane of the spiral arms of the galaxy. The proposed likely interpretation is that a dwarf galaxy is merging with the Milky Way. This galaxy is tentatively named the Virgo Stellar Stream and is found in the direction of Virgo about 30,000 light-years away.

Sun's location and neighborhood

The Sun (and therefore the Earth and the Solar System) may be found close to the inner rim of the galaxy's Orion Arm, in the Local Fluff inside the Local Bubble, and in the Gould Belt, at a distance of 7.62±0.32 kpc (~25,000±1,000 ly) from the Galactic Center.[35][36][37][38][39] The Sun is currently 5–30 parsecs from the central plane of the galactic disc.[39] The distance between the local arm and the next arm out, the Perseus Arm, is about 6,500 light-years.[40] The Sun, and thus the Solar System, is found in the galactic habitable zone.

There are about 208 stars brighter than absolute magnitude 8.5 within 15 parsecs of the Sun, giving a density of 0.0147 such stars per cubic parsec, or 0.000424 per cubic light-year (from List of nearest bright stars). On the other hand, there are 64 known stars (of any magnitude, not counting 4 brown dwarfs) within 5 parsecs of the Sun, giving a density of 0.122 stars per cubic parsec, or 0.00352 per cubic light-year (from List of nearest stars), illustrating the fact that most stars are less bright than absolute magnitude 8.5.

The Apex of the Sun's Way, or the solar apex, is the direction that the Sun travels through space in the Milky Way. The general direction of the Sun's galactic motion is towards the star Vega near the constellation of Hercules, at an angle of roughly 60 sky degrees to the direction of the Galactic Center. The Sun's orbit around the Galaxy is expected to be roughly elliptical with the addition of perturbations due to the galactic spiral arms and non-uniform mass distributions. In addition, the Sun oscillates up and down relative to the galactic plane approximately 2.7 times per orbit. This is very similar to how a simple harmonic oscillator works with no drag force (damping) term. These oscillations often coincide with mass extinction periods on Earth; presumably the higher density of stars close to the galactic plane leads to more impact events.[41]

It takes the Solar System about 225–250 million years to complete one orbit of the galaxy (a galactic year),[42] so it is thought to have completed 20–25 orbits during the lifetime of the Sun and 1/1250 of a revolution since the origin of humans. The orbital speed of the Solar System about the center of the Galaxy is approximately 220 km/s. At this speed, it takes around 1,400 years for the Solar System to travel a distance of 1 light-year, or 8 days to travel 1 AU (astronomical unit).[43]

Environment

The Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy are a binary system of giant spiral galaxies belonging to a group of 50 closely bound galaxies known as the Local Group, itself being part of the Virgo Supercluster.

Two smaller galaxies and a number of dwarf galaxies in the Local Group orbit the Milky Way. The largest of these is the Large Magellanic Cloud with a diameter of 20,000 light-years. It has a close companion, the Small Magellanic Cloud. The Magellanic Stream is a peculiar streamer of neutral hydrogen gas connecting these two small galaxies. The stream is thought to have been dragged from the Magellanic Clouds in tidal interactions with the Milky Way. Some of the dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way are Canis Major Dwarf (the closest), Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy, Ursa Minor Dwarf, Sculptor Dwarf, Sextans Dwarf, Fornax Dwarf, and Leo I Dwarf. The smallest Milky Way dwarf galaxies are only 500 light-years in diameter. These include Carina Dwarf, Draco Dwarf, and Leo II Dwarf. There may still be undetected dwarf galaxies, which are dynamically bound to the Milky Way, as well as some that have already been absorbed by the Milky Way, such as Omega Centauri. Observations through the zone of avoidance are frequently detecting new distant and nearby galaxies. Some galaxies consisting mostly of gas and dust may also have evaded detection so far.

In January 2006, researchers reported that the heretofore unexplained warp in the disk of the Milky Way has now been mapped and found to be a ripple or vibration set up by the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds as they circle the Galaxy, causing vibrations at certain frequencies when they pass through its edges.[44] Previously, these two galaxies, at around 2% of the mass of the Milky Way, were considered too small to influence the Milky Way. However, by taking into account dark matter, the movement of these two galaxies creates a wake that influences the larger Milky Way. Taking dark matter into account results in an approximately twenty-fold increase in mass for the Galaxy. This calculation is according to a computer model made by Martin Weinberg of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. In this model, the dark matter is spreading out from the galactic disc with the known gas layer. As a result, the model predicts that the gravitational effect of the Magellanic Clouds is amplified as they pass through the Galaxy.

Current measurements suggest the Andromeda Galaxy is approaching us at 100 to 140 kilometers per second. The Milky Way may collide with it in 3 to 4 billion years, depending on the importance of unknown lateral components to the galaxies' relative motion. If they collide, individual stars within the galaxies would not collide, but instead the two galaxies will merge to form a single elliptical galaxy over the course of about a billion years.[45]

Velocity

In the general sense, the absolute velocity of any object through space is not a meaningful question according to Einstein's special theory of relativity, which declares that there is no "preferred" inertial frame of reference in space with which to compare the object's motion. (Motion must always be specified with respect to another object.) This must be kept in mind when discussing the Galaxy's motion.

Astronomers believe the Milky Way is moving at approximately 630 km per second relative to the local co-moving frame of reference that moves with the Hubble flow.[49] If the Galaxy is moving at 600 km/s, Earth travels 51.84 million km per day, or more than 18.9 billion km per year, about 4.5 times its closest distance from Pluto. The Milky Way is thought to be moving in the direction of the Great Attractor. The Local Group (a cluster of gravitationally bound galaxies containing, among others, the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxy) is part of a supercluster called the Local Supercluster, centered near the Virgo Cluster: although they are moving away from each other at 967 km/s as part of the Hubble flow, the velocity is less than would be expected given the 16.8 million pc distance due to the gravitational attraction between the Local Group and the Virgo Cluster.[50]

Another reference frame is provided by the cosmic microwave background (CMB). The Milky Way is moving at around 552 km/s[7] with respect to the photons of the CMB, toward 10.5 right ascension, -24° declination (J2000 epoch, near the center of Hydra). This motion is observed by satellites such as the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) and the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) as a dipole contribution to the CMB, as photons in equilibrium in the CMB frame get blue-shifted in the direction of the motion and red-shifted in the opposite direction.[citation needed]

The galaxy rotates about its center according to its galaxy rotation curve as shown in the figure. The discrepancy between the observed curve (relatively flat) and the curve based upon the known mass of the stars and gas in the Milky Way (decaying curve) is attributed to dark matter.[51]

History

Etymology and beliefs

There are many creation myths around the world which explain the origin of the Milky Way and give it its name. The English phrase is a translation from Ancient Greek Γαλαξίας, Galaxias, which is derived from the word for milk (γάλα, gala). This is also the origin of the word galaxy. In Greek myth, the Milky Way was caused by milk spilt by Hera when suckling Heracles.

In Sanskrit and several other Indo-Aryan languages, the Milky Way is called Akash Ganga (आकाशगंगा, Ganges of the heavens).[52] The milky way is held to be sacred in the Hindu scriptures known as the Puranas, and the Ganges and the milky way are considered to be terrestrial-celestial analogs of each other.[52][53] However, the term Kshira (क्षीर, milk) is also used as an alternative name for the milky way in Hindu texts.[54]

In a large area from Central Asia to Africa, the name for the Milky Way is related to the word for "straw". This may have originated in ancient Armenian mythology, (Յարդ զողի Ճանապարհ hard goghi chanaparh, or "Trail of the Straw Thief"), and been carried abroad by Arabs.[55] In several Uralic, Turkic languages, Fenno-Ugric languages and in the Baltic languages the Milky Way is called the "Birds' Path" (Linnunrata in Finnish), since the route of the migratory birds appear to follow the Milky Way. (The Qi Xi legend celebrated in many Asian cultures references a seasonal bridge across the Milky Way formed by birds, usually magpies or crows.) The Chinese name "Silver River" (銀河) is used throughout East Asia, including Korea and Japan. An alternative name for the Milky Way in ancient China, especially in poems, is "Heavenly Han River"(天汉). In Japanese, "Silver River" (銀河 ginga) means galaxies in general and the Milky Way is called the "Silver River System" (銀河系 gingakei) or the "River of Heaven" (天の川 Amanokawa or Amanogawa). In Swedish, it is called Vintergatan, or "Winter Avenue", because the stars in the belt were used to predict when winter would arrive.[citation needed] In some of the Iberian languages, the Milky Way's name translates as the "Road of Saint James" (e.g., in Spanish it is sometimes called "El camino de Santiago").

Discovery

As Aristotle (384-322 BC) informs us in Meteorologica (DK 59 A80), the Greek philosophers Anaxagoras (ca. 500–428 BC) and Democritus (450–370 BC) proposed the Milky Way might consist of distant stars. However, Aristotle himself believed the Milky Way to be caused by "the ignition of the fiery exhalation of some stars which were large, numerous and close together" and that the "ignition takes place in the upper part of the atmosphere, in the region of the world which is continuous with the heavenly motions."[56] The Arabian astronomer, Alhazen (965-1037 AD), refuted this by making the first attempt at observing and measuring the Milky Way's parallax,[57] and he thus "determined that because the Milky Way had no parallax, it was very remote from the earth and did not belong to the atmosphere."[58]

The Persian astronomer Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (973-1048) proposed the Milky Way galaxy to be a collection of countless nebulous stars.[59] The Andalusian astronomer Avempace (d. 1138) proposed the Milky Way to be made up of many stars but appears to be a continuous image due to the effect of refraction in the Earth's atmosphere, citing his observation of the conjunction of Jupiter and Mars on 500 AH (1106/1107 AD) as evidence.[56] Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya (1292-1350) proposed the Milky Way galaxy to be "a myriad of tiny stars packed together in the sphere of the fixed stars" and that that these stars are larger than planets.[60]

Actual proof of the Milky Way consisting of many stars came in 1610 when Galileo Galilei used a telescope to study the Milky Way and discovered that it was composed of a huge number of faint stars.[61] In a treatise in 1755, Immanuel Kant, drawing on earlier work by Thomas Wright, speculated (correctly) that the Milky Way might be a rotating body of a huge number of stars, held together by gravitational forces akin to the Solar System but on much larger scales. The resulting disk of stars would be seen as a band on the sky from our perspective inside the disk. Kant also conjectured that some of the nebulae visible in the night sky might be separate "galaxies" themselves, similar to our own.[62]

The first attempt to describe the shape of the Milky Way and the position of the Sun within it was carried out by William Herschel in 1785 by carefully counting the number of stars in different regions of the visible sky. He produced a diagram of the shape of the Galaxy with the Solar System close to the center.

In 1845, Lord Rosse constructed a new telescope and was able to distinguish between elliptical and spiral-shaped nebulae. He also managed to make out individual point sources in some of these nebulae, lending credence to Kant's earlier conjecture.[63]

In 1917, Heber Curtis had observed the nova S Andromedae within the "Great Andromeda Nebula" (Messier object M31). Searching the photographic record, he found 11 more novae. Curtis noticed that these novae were, on average, 10 magnitudes fainter than those that occurred within our galaxy. As a result he was able to come up with a distance estimate of 150,000 parsecs. He became a proponent of the "island universes" hypothesis, which held that the spiral nebulae were actually independent galaxies.[64] In 1920 the Great Debate took place between Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis, concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral nebulae, and the dimensions of the universe. To support his claim that the Great Andromeda Nebula was an external galaxy, Curtis noted the appearance of dark lanes resembling the dust clouds in the Milky Way, as well as the significant Doppler shift.[65]

The matter was conclusively settled by Edwin Hubble in the early 1920s using a new telescope. He was able to resolve the outer parts of some spiral nebulae as collections of individual stars and identified some Cepheid variables, thus allowing him to estimate the distance to the nebulae: they were far too distant to be part of the Milky Way.[66] In 1936, Hubble produced a classification system for galaxies that is used to this day, the Hubble sequence.[67]

See also

- Galactic coordinate system

- Dark matter halo

- Smith's Cloud

- Oort Constants

- The Great Rift, a molecular dust cloud located between the solar system and the Sagittarius Arm of the Milky Way which appears to split the Milky Way into two lanes over a third of its length

- MilkyWay@Home, a distributed computing project that attempts to generate highly accurate three-dimensional dynamic models of stellar streams in the immediate vicinity of our Milky Way galaxy.

References

- ^ a b c Christian, Eric; Samar, Safi-Harb. "How large is the Milky Way?". Retrieved 2007-11-28.

- ^ http://www.nasa.gov/worldbook/galaxy_worldbook.html

- ^ http://www.scientific-web.com/en/Astronomy/Galaxies/MilkyWay.html

- ^ http://www.universetoday.com/guide-to-space/milky-way/how-many-stars-are-in-the-milky-way/

- ^ a b Frebel, Anna (2007). "Discovery of HE 1523-0901, a Strongly r-Process-enhanced Metal-poor Star with Detected Uranium". The Astrophysical Journal. 660: L117. doi:10.1086/518122. arXiv:astro-ph/0703414.

- ^ a b Bissantz, Nicolai (2003). "Gas dynamics in the Milky Way: second pattern speed and large-scale morphology". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 340: 949. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2003.06358.x. arXiv:astro-ph/0212516.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Kogut, A.; Lineweaver, C.; Smoot, G. F.; Bennett, C. L.; Banday, A.; Boggess, N. W.; Cheng, E. S.; de Amici, G.; Fixsen, D. J.; Hinshaw, G.; Jackson, P. D.; Janssen, M.; Keegstra, P.; Loewenstein, K.; Lubin, P.; Mather, J. C.; Tenorio, L.; Weiss, R.; Wilkinson, D. T.; Wright, E. L. (1993). "Dipole Anisotropy in the COBE Differential Microwave Radiometers First-Year Sky Maps". Astrophysical Journal. 419: 1. doi:10.1086/173453. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Freedman, Roger A. (2007). Universe. WH Freeman & Co. p. 605. ISBN 0-7167-8584-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

"Galaxies — Milky Way Galaxy". Encyclopedia Britannica. Vol. 19. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. 1998. pp. p. 618.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Pasachoff, Jay M. (1994). Astronomy: From the Earth to the Universe. Harcourt School. p. 500. ISBN 0-03-001667-3.

- ^ Sanders, Robert (January 9, 2006). "Milky Way Galaxy is warped and vibrating like a drum". UCBerkeley News. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- ^ Frommert, H.; Kronberg, C. (August 25, 2005). "The Milky Way Galaxy". SEDS. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Young, Kelly (2006-06-06). "Andromeda galaxy hosts a trillion stars". NewScientist. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ^ http://arxiv.org/abs/0909.3857

- ^ "Milky Way fatter than first thought". The Sydney Morning Herald. Australian Associated Press. 2008-02-20. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ^ Connors; et al. (2007). "N-body simulations of the Magellanic stream". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 371: 108. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10659.x. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Milky Way a Swifter Spinner, More Massive, New Measurements Show". 2009-01-05. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ^ Ron Cowen (January 5, 2009). "This just in: Milky Way as massive as 3 trillion suns". Society for Science & the Public. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ^ Del Peloso, E. F. (2005). "The age of the Galactic thin disk from Th/Eu nucleocosmochronology". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 440: 1153. Bibcode:2005A&A...440.1153D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053307. arXiv:astro-ph/0506458.

- ^ Ortwin, Gerhard (2002). "Mass distribution in our galaxy". Space Science Reviews. 100 (1/4): 129–138. doi:10.1023/A:1015818111633. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ Chen, W.; Gehrels, N.; Diehl, R.; Hartmann, D. (1996). "On the spiral arm interpretation of COMPTEL ^26^Al map features". Space Science Reviews. 120: 315–316. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McKee, Maggie (August 16, 2005). "Bar at Milky Way's heart revealed". New Scientist. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ^ Karachentsev, I. D.; Kashibadze, O. G. (2006). "Masses of the local group and of the M81 group estimated from distortions in the local velocity field". Astrophysics. 49 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1007/s10511-006-0002-6.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vayntrub, Alina (2000). "Mass of the Milky Way". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ^ a b Battaglia, G.; Helmi, A.; Morrison, H.; Harding, P.; Olszewski, E. W.; Mateo, M.; Freeman, K. C.; Norris, J.; Shectman, S. A. (2005). "The radial velocity dispersion profile of the Galactic halo: Constraining the density profile of the dark halo of the Milky Way" (abstract). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 364: 433–442. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grant. J.; Lin, B. (2000). "The Stars of the Milky Way". Fairfax Public Access Corporation. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mark H. Jones, Robert J. Lambourne, David John Adams (2004). An Introduction to Galaxies and Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 0521546230.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blandford, R.D. (1999). "Origin and evolution of massive black holes in galactic nuclei". Galaxy Dynamics, proceedings of a conference held at Rutgers University, 8–12 Aug 1998,ASP Conference Series vol. 182.

{{cite conference}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff (September 12, 2005). "Introduction: Galactic Ring Survey". Boston University. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ a b Benjamin, R. A. (2008). "The Spiral Structure of the Galaxy: Something Old, Something New...". In Beuther, H.; Linz, H.; Henning, T. (ed.) (ed.). Massive Star Formation: Observations Confront Theory. Vol. 387. Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series. p. 375.

{{cite conference}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

See also Bryner, Jeanna (2008-06-03). "New Images: Milky Way Loses Two Arms". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-06-04. - ^ Imamura, Jim (August 10, 2006). "Mass of the Milky Way Galaxy". University of Oregon. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Harris, William E. (2003). "Catalog of Parameters for Milky Way Globular Clusters: The Database" (text). SEDS. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ibata, R.; Chapman, S.; Ferguson, A. M. N.; Lewis, G.; Irwin, M.; Tanvir, N. (2005). "On the accretion origin of a vast extended stellar disk around the Andromeda Galaxy". Astrophysical Journal. 634 (1): 287–313. doi:10.1086/491727. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Outer Disk Ring?". SolStation. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Reid, Mark J. (1993). "The distance to the center of the galaxy". Annual review of astronomy and astrophysics. 31: 345–372. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.31.090193.002021. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Eisenhauer, F.; Schödel, R.; Genzel, R.; Ott, T.; Tecza, M.; Abuter, R.; Eckart, A.; Alexander, T. (2003). "A Geometric Determination of the Distance to the Galactic Center". The Astrophysical Journal. 597: L121–L124. doi:10.1086/380188. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Horrobin, M.; Eisenhauer, F.; Tecza, M.; Thatte, N.; Genzel, R.; Abuter, R.; Iserlohe, C.; Schreiber, J.; Schegerer, A.; Lutz, D.; Ott, T.; Schödel, R. (2004). "First results from SPIFFI. I: The Galactic Center" (PDF). Astronomische Nachrichten. 325: 120–123. doi:10.1002/asna.200310181. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eisenhauer, F.; et al. (2005). "SINFONI in the Galactic Center: Young Stars and Infrared Flares in the Central Light-Month". The Astrophysical Journal. 628 (1): 246–259. doi:10.1086/430667. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b

Majaess, D. J. (2009). "Characteristics of the Galaxy according to Cepheids". MNRAS. 398: 263–270. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15096.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ English, Jayanne (1991-07-24). "Exposing the Stuff Between the Stars". Hubble News Desk. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Gillman, M. and Erenler, H. (2008). "The galactic cycle of extinction". International Journal of Astrobiology. 7. doi:10.1017/S1473550408004047. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leong, Stacy (2002). "Period of the Sun's Orbit around the Galaxy (Cosmic Year)". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Garlick, Mark Antony (2002). The Story of the Solar System. Cambridge University. p. 46. ISBN 0521803365.

- ^ "Milky Way galaxy is warped and vibrating like a drum" (Press release). University of California, Berkeley. 2006-01-09. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ Wong, Janet (April 14, 2000). "Astrophysicist maps out our own galaxy's end". University of Toronto. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ^ Peter Schneider (2006). Extragalactic Astronomy and Cosmology. Springer. p. 4, Figure 1.4. ISBN 3540331743.

- ^ Theo Koupelis, Karl F Kuhn (2007). In Quest of the Universe. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 492; Figure 16-13. ISBN 0763743879.

- ^ Mark H. Jones, Robert J. Lambourne, David John Adams (2004). An Introduction to Galaxies and Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. p. 21; Figure 1.13. ISBN 0521546230.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mark H. Jones, Robert J. Lambourne, David John Adams (2004). An Introduction to Galaxies and Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 0521546230.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peirani, S (2006). "Mass determination of groups of galaxies: Effects of the cosmological constant". New Astronomy. 11: 325. doi:10.1016/j.newast.2005.08.008.

- ^ Theo Koupelis, Karl F. Kuhn (2007). In Quest of the Universe. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 492, Figure 16–13. ISBN 0763743879.

- ^ a b A M T Jackson, R.E. Enthoven (1989), Folk Lore Notes, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 8120604857,

... According to the Puranas, the milky way or akashganga is the celestial River Ganga which was brought down by Bhagirath ...

- ^ Hormusjee Shapoorjee Spencer (1965), The Aryan ecliptic cycle: glimpses into ancient Indo-Iranian religious history from 25628 B.C. to 292 A.D., H.P. Vaswani,

... There are two "Gangas" — one terrestrial and the other "akashic" or celestial ... bear reference only to the "Akash Ganga" which is the Milky Way ...

- ^ Edward C. Sachau (2001), Alberuni's India: an account of the religion, philosophy, literature, geography, chronology, astronomy, customs, laws and astrology of India about A.D. 1030, Routledge,

... revolves around Kshira, i.e. the Milky Way ...

- ^ Harutyunyan, Hayk (2003-08-29). "The Armenian name of the Milky Way" ([dead link] – Scholar search). ArAS News. 6. Armenian Astronomical Society (ArAS). Retrieved 2007-01-05.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format= - ^ a b Josep Puig Montada (September 28, 2007). "Ibn Bajja". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ Mohamed, Mohaini (2000), Great Muslim Mathematicians, Penerbit UTM, pp. 49–50, ISBN 9835201579

- ^ Hamid-Eddine Bouali, Mourad Zghal, Zohra Ben Lakhdar (2005). "Popularisation of Optical Phenomena: Establishing the First Ibn Al-Haytham Workshop on Photography" (PDF). The Education and Training in Optics and Photonics Conference. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Livingston, John W. (1971), "Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah: A Fourteenth Century Defense against Astrological Divination and Alchemical Transmutation", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 91 (1): 96–103 [99], doi:10.2307/600445

- ^ O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (2002). "Galileo Galilei". University of St Andrews. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evans, J. C. (November 24 1998). "Our Galaxy". George Mason University. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Abbey, Lenny. "The Earl of Rosse and the Leviathan of Parsontown". The Compleat Amateur Astronomer. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ^ Heber D. Curtis (1988). "Novae in Spiral Nebulae and the Island Universe Theory". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 100: 6. doi:10.1086/132128.

- ^ Weaver, Harold F. "Robert Julius Trumpler". National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ Hubble, E. P. (1929). "A spiral nebula as a stellar system, Messier 31". Astrophysical Journal. 69: 103–158. doi:10.1086/143167.

- ^ Sandage, Allan (1989). "Edwin Hubble, 1889–1953". The Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 83 (6). Retrieved 2007-01-08.

Further reading

- Thorsten Dambeck in Sky and Telescope, "Gaia's Mission to the Milky Way", March 2008, p. 36–39.

External links

- The Milky Way Galaxy from An Atlas of the Universe

- A 3D map of the Milky Way Galaxy

- Chromoscope Tools to Explore the known Milky Way

- Milky Way – IRAS (infrared) survey wikisky.org

- Milky Way – H-Alpha survey wikisky.org

- Interactive full screen Silverlight map of the Milky Way

- Running Rings Around the Galaxy Spitzer Space Telescope News

- The Milky Way Galaxy, SEDS Messier pages

- MultiWavelength Milky Way, NASA site with images and VRML models

- Milky Way Explorer, detailed images in infrared with radio, microwave and hydrogen-alpha as well

- Face-on Milky Way maps, within about 10 thousand parsecs

- The Milky Way at the Astro-Photography Site Of Mister T. Yoshida.

- Widefield Image of the Summer Milky Way

- Proposed Ring around the Milky Way

- Milky Way spiral gets an extra arm, New Scientist.com

- Possible New Milky Way Spiral Arm, Sky and Telescope.com

- The Milky Way spiral arms and a possible climate connection

- Galactic center mosaic via sun-orbiting Spitzer infrared telescope

- Milky Way Plan Views, The University of Calgary Radio Astronomy Laboratory

- Our Growing, Breathing Galaxy, Scientific American Magazine (January 2004 Issue)

- Deriving The Shape Of The Galactic Stellar Disc, SkyNightly (March 17, 2006)

- Digital Sky LLC, Digital Sky's Milky Way Panorama and other images

- A new view of the Milky Way galaxy obtained by the Diffuse Infrared Background Experiment (DIRBE) on NASA's Cosmic Background Explorer satellite (COBE).

- Image of Milky Way galaxy arms, Chandra X-ray Observatory Center

- The 1920 Shapley – Curtis Debate on the size of the Milky Way

- Milky Way Voyage – India's First & Largest Star Party

- Astronomy Picture of the Day:

- Moving Milkyway seen from Teneriffe without any lightpollution

- Multi-Gigapixel Infrared Milky Way A zoomable, annotated version of the Spitzer Space Telescope GLIMPSE survey.

- Animated tour of the Milky Way, University of Glamorgan