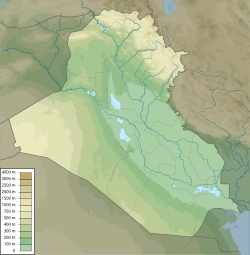

Karbala or Kerbala (/ˈkɑːrbələ/ KAR-bə-lə,[2][3] US also /ˌkɑːrbəˈlɑː/ KAR-bə-LAH;[4][5] Arabic: كَرْبَلَاء, romanized: Karbalāʾ, IPA: [karbaˈlaːʔ]) is a city in central Iraq, located about 100 km (62 mi) southwest of Baghdad, and a few miles east of Lake Milh, also known as Razzaza Lake.[6][7] Karbala is the capital of Karbala Governorate, and has an estimated population of 691,100 people (2024).[8]

Karbala

كَرْبَلَاء | |

|---|---|

| Mayoralty of Karbala | |

| |

| |

| Coordinates: 32°37′N 44°02′E / 32.617°N 44.033°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Karbala |

| Settled | 690 CE |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 42.4 km2 (16.4 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 28 m (92 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018)[1] | 711,530 |

| Demonym | Karbalaei |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (Arabian Standard Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (No DST) |

| Postal code | 10001 to 10090 |

The city, best known as the location of the Battle of Karbala in 680 AD, or for the shrines of Hussain and Abbas,[9][10] is considered a holy city for Shia Muslims. Tens of millions of Shi'ite Muslims visit the site twice a year. [11][12][13][14] The martyrdom of Husayn ibn 'Ali and Abbas ibn 'Ali is commemorated annually by near a hundred million of Shi'ites in the city.[11][12][13][15]

Up to 34 million pilgrims visit the city to observe ʿĀshūrāʾ (the tenth day of Muharram), which marks the anniversary of Husayn's death, but the main event is the Arbaʿeen (the 40th day after 'Ashura'), where up to 40 million visit the graves. Most of the pilgrims travel on foot and come from all around Iraq and more than 56 countries.[16]

Etymology

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2023) |

There are many opinions among different investigators, as to the origin of the word Karbala. Some have pointed out that Karbala has a connection to the "Karbalato" language, while others attempt to derive the meaning of word by analyzing its spelling and language.[clarification needed] They conclude that it originates from the "Kar Babel" group of ancient Babylonian villages that included Nainawa, Al-Ghadiriyya, Karbella (or Karb Illu), Al-Nawaweess, and Al-Heer. This last name is today known as Al-Hair and is where Husayn ibn Ali's grave is located.

The investigator Yaqut al-Hamawi had pointed out that the meaning of Karbala could have several explanations, one of which is that the place where Husayn ibn Ali was martyred is made of soft earth—al-Karbalāt.

According to Shia's belief, the archangel Gabriel narrated the true meaning of the name Karbala to Muhammad: a combination of karb (Arabic: كَرْب, "the land which will cause many agonies") and balāʾ (Arabic: بَلاء, "afflictions").[17]

History

editBattle of Karbala

editThe Battle of Karbala was fought on the bare deserts on the way to Kufa on October 10, 680 AD (10 Muharram 61 AH). Both Husayn ibn Ali and his brother Abbas ibn Ali were buried by the local Banī Asad tribe, at what later became known as the Mashhad Al-Husayn. The battle itself occurred as a result of Husain's refusal of Yazid's demand for allegiance to his caliphate. The Kufan governor, Ubaydallah ibn Ziyad, sent thirty thousand horsemen against Husayn as he traveled to Kufa. Husayn had no army, he was with his family and few friends who joined them, so there were around 73 men, including the 6-month-old Ali Asghar, son of Imam Husayn, in total. The horsemen, under 'Umar ibn Sa'd, were ordered to deny Husayn and his followers water in order to force Husayn to agree to give an oath of allegiance. On the 9th of Muharram, Husayn refused, and requested to be given the night to pray. On the 10th day of Muharram, Husayn ibn Ali prayed the morning prayer and led his troops into battle along with his brother Abbas. Many of Husayn's followers, including all of his present sons Ali Akbar, Ali Asghar (six months old) and his nephews Qassim, Aun and Muhammad were killed.[18]

In 63 AH (683 AD), Yazid ibn Mu'awiya released the surviving members of Husayn's family from prison as there was a threat of uprisings and some of the people in his court were unaware of who the battle was with, when they got to know that the descendants of Muhammad were killed, they were horrified. On their way to Mecca, they stopped at the site of the battle. There is record of Sulayman ibn Surad going on pilgrimage to the site as early as 65 AH (685 AD). The city began as a tomb and shrine to Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of Muhammad and son of Ali ibn Abi Talib,[19] and grew as a city in order to meet the needs of pilgrims. The city and tombs were greatly expanded by successive Muslim rulers, but suffered repeated destruction from attacking armies. The original shrine was destroyed by the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mutawakkil in 850 but was rebuilt in its present form around 979, only to be partly destroyed by fire in 1086 and rebuilt yet again.

Early modern

editLike Najaf, the city suffered from severe water shortages that were only resolved in the early 18th century by building a dam at the head of the Husayniyya Canal. In 1737, the city replaced Isfahan in Iran as the main centre of Shia scholarship. In the mid-eighteenth century it was dominated by the dean of scholarship, Yusuf Al Bahrani, a key proponent of the Akhbari tradition of Shia thought, until his death in 1772,[20] after which the more state-centric Usuli school became more influential.

The Wahhabi sack of Karbala occurred on 21 April 1802 (1216 Hijri) (1801),[21] under the rule of Abdul-Aziz bin Muhammad the second ruler of the First Saudi State, when 12,000 Wahhabi Muslims from Najd attacked the city of Karbala.[22] The attack was coincident with the anniversary of Ghadir Khum event,[23] or 10 Muharram.[19] This fight left 3,000–5,000 deaths and the dome of the tomb of Husayn ibn Ali,[19] was destroyed. The fight lasted for 8 hours.[24]

After the First Saudi State invasion, the city enjoyed semi-autonomy during Ottoman rule, governed by a group of gangs and mafia variously allied with members of the 'ulama. In order to reassert their authority, the Ottoman army laid siege to the city. On January 13, 1843, Ottoman troops entered the city. Many of the city leaders fled leaving defense of the city largely to tradespeople. About 3,000 Arabs were killed in the city, and another 2,000 outside the walls (this represented about 15% of the city's normal population). The Turks lost 400 men.[25] This prompted many students and scholars to move to Najaf, which became the main Shia religious centre.[26] Between 1850 and 1903, Karbala enjoyed a generous influx of money through the Oudh Bequest. The Shia-ruled Indian Province of Awadh, known by the British as Oudh, had always sent money and pilgrims to the holy city. The Oudh money, 10 million rupees, originated in 1825 from the Awadh Nawab Ghazi-ud-Din Haider. One third was to go to his wives, and the other two-thirds went to holy cities of Karbala and Najaf. When his wives died in 1850, the money piled up with interest in the hands of the British East India Company. The EIC sent the money to Karbala and Najaf per the wives' wishes, in the hopes of influencing the Ulama in Britain's favor. This effort to curry favor is generally considered to have been a failure.[27]

In 1915, Karbala was the scene of an uprising against the Ottoman Empire.[28]

In 1928, an important drainage project was carried out to relieve the city of unhealthy swamps, formed between Hussainiya and the Bani Hassan Canals on the Euphrates.[29]

Defense of the City Hall in Karbala – a series of skirmishes fought from April 3 to April 6, 2004, between the Iraqi rebels of the Mahdi Army trying to conquer the city hall and the defending Polish and Bulgarian soldiers from the Multinational Division Central-South

In 2003 following the American invasion, the Karbala town council attempted to elect United States Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Lopez as mayor. Ostensibly so that his Marines, contractors, and funds could not leave.[30]

On April 14, 2007, a car bomb exploded about 600 ft (180 m) from the shrine to Husayn, killing 47[31] and wounding over 150.

On January 19, 2008, 2 million Iraqi Shia pilgrims marched through Karbala city, Iraq to commemorate Ashura. 20,000 Iraqi troops and police guarded the event amid tensions due to clashes between Iraqi troops and Shia which left 263 people dead (in Basra and Nasiriya).[32]

Geography

editClimate

editKarbala experiences a hot desert climate (BWh in the Köppen climate classification) with extremely hot, long, dry summers and mild winters. Almost all of the yearly precipitation is received between November and April, though no month is wet.

| Climate data for Karbala (1991-2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 16.6 (61.9) |

19.5 (67.1) |

24.6 (76.3) |

31.3 (88.3) |

37.6 (99.7) |

42.4 (108.3) |

44.7 (112.5) |

44.7 (112.5) |

40.9 (105.6) |

34.2 (93.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

31.6 (88.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

23.9 (75.0) |

29.7 (85.5) |

33.9 (93.0) |

36.4 (97.5) |

35.9 (96.6) |

32.3 (90.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

27.6 (81.7) |

29.8 (85.6) |

29.3 (84.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

18.3 (64.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 17.6 (0.69) |

14.5 (0.57) |

14.1 (0.56) |

11.9 (0.47) |

2.4 (0.09) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

4.1 (0.16) |

14.8 (0.58) |

13.8 (0.54) |

93.5 (3.67) |

| Average precipitation days | 7 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 42 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72.1 | 60.7 | 49.8 | 42.5 | 34.1 | 28.2 | 28.6 | 30.2 | 34.9 | 44.7 | 61.5 | 70.5 | 46.5 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organisation (precipitation days 1976-2008)[33] [34] | |||||||||||||

Religious significance

editMesopotamia in the Quran

editSome Shi'ites consider this verse of the Quran to refer to Iraq, land of the Shi'ite sacred sites of Kufah,[38][39] Najaf, Karbala, Kadhimiyyah[a] and Samarra,[41][42] since the Monotheistic preachers Ibrāhīm (Abraham) and Lūṭ (Lot),[43] who are regarded as Prophets in Islam,[44] are believed to have lived in the ancient Iraqi city of Kutha Rabba,[45] before going to "The Blessed Land".[46]

Then We delivered him(Ibrahim), along with Lot, to the land We had showered with blessings for all people.

Aside from the story of Abraham and Lot in Polytheistic[47] Mesopotamia,[45][46] there are passages in the Quran about Mount Judi,[48][49][50] Babil ("Babylon")[51][52] and Qaryat Yunus ("Town of Jonah").[35][36][37]

Hadith

editThe tomb of the martyred Imam has acquired great significance in Shia tradition because he and his fellow martyrs are seen as models of jihad in the way of God. Shi'ites believe that Karbala is one of the holiest places on Earth according to the following traditions (among others):

Karbala, where your grandson and his family will be martyred, is one of the most blessed and the most sacred lands on Earth, and it is one of the valleys of Paradise.

- The fourth Shi'ite Imam, that is Zayn al-Abidin narrated:[53]

God chose the land of Karbalā' as a safe and blessed sanctuary twenty-four thousand years before He created the land of the Ka'bah and chose it as a sanctuary. Verily it (Karbala) will shine among the gardens of Paradise like a shining star shines among the stars for the people of Earth.

- In this regard, Ja'far al-Sadiq narrates, 'Allah, the Almighty, has made the dust of my ancestor's grave – Imam Husain (r.a) as a cure for every sickness and safety from every fear.'[54]

- It is narrated from Ja'far that: "The earth of the pure and holy grave of Husayn ibn ‘Ali (r.a) is a pure and blessed musk. For those who consume it, it is a cure for every ailment, and if our enemy uses it then he will melt the way fat melts, when you intend to consume that pure earth recite the following supplication"[55]

Culture

editReligious tourism

editKarbala, alongside Najaf, is considered a thriving tourist destination for Shia Muslims and the tourism industry in the city boomed after the end of Saddam Hussein's rule.[56] Some religious tourism attractions include:

- Al Abbas Mosque

- Imam Husayn Shrine

- Euphrates

- Ruins of Mujada, about 40 km (25 miles) to the west of the city[57][58]

Arbaeen is a massive annual pilgrimage event that takes place in Karbala. It is considered one of the largest peaceful gatherings in the world. In 2017, approximately 30 million people took part in the pilgrimage.

Sports

editKarbala FC is a football club based in Karbala. It plays in the top tier Iraq Stars League, the highest division of the Iraqi football league system.

The Karbala Sports City located south of Karbala city, is a large sports complex housing the Karbala International Stadium with a capacity of 30,000 spectators, a smaller football stadium with a capacity of 2,000, as well as a football field for training, a swimming hall, and a hotel.

Popular culture

editThere are many references in books and films to Karbala, specifically referring to Imam Husayn's death at the Battle of Karbala. One such example is the Iranian film Hussein Who Said No. In paintings, Husayn is often depicted on a white horse impaled by arrows.[citation needed] A number of documentaries detailing the events of the Battle of Karbala have also been produced.

Karbala in other cultures

editIn the Indian subcontinent, Karbala, apart from meaning the city of Karbala (which is usually referred to as Karbala-e-Mualla meaning Karbala the exalted), also means local grounds where commemorative processions end and/or ta'zīya are buried during Ashura or Arba'een, usually such grounds will have shabeeh (copy) of Rauza or some other structures.[59][60]

In South Asia where ta'zīya refer to specifically to the miniature mausoleums used in processions held in Muharram. It all started from the fact that the great distance of India from Karbala prevented Indian Shi'is being buried near the tomb of Husayn or making frequent pilgrimages (ziyarat) to the tomb. This is the reason why Indian Shi'is established local karbalas on the subcontinent by bringing soil from Karbala and sprinkling it on lots designated as future cemeteries. Once the karbalas were established on the subcontinent, the next step was to bring Husayn's tomb-shrine to India. This was established by building replicas of Husayn's mausoleum called ta'zīya to be carried in Muharram processions. Thousands of ta'zīyas in various shapes and sizes are made every year for the months of mourning of Muharram and Safar; and are carried in processions and may be buried at the end of Ashura or Arba'een.[61]

Education

editUniversities

editUniversity of Karbala, which was inaugurated on March 1, 2002, is one of the top most universities in Iraq regarding academic administration, human resources, and scientific research.[62] Ahl al-Bayt University was founded in September 2003 by Dr. Mohsen Baqir Mohammed-Salih Al-Qazwini. The university has six major colleges: College of Law, Arts, Islamic Sciences, Medical & Health Technology, Pharmacy and Dentistry.[63]

Warith al-Anbiya University in Karbala, sponsored by the Imam Husayn Holy Shrine, was established in 2017. It has the faculties of engineering, administration, economics, law and pathology. It received its first batch of students in the academic year 2017–2018.[64]

Hawza Seminary

editThe Hawza are Islamic education institutions that are administered under the guidance of a Grand Ayatollah or group of scholars to teach Shia Muslims and guide them through the rigorous journey of becoming an Alim (a religious scholar). Initially Karbala's hawza consisted mostly of Iranians and Turkish scholars. The death of Sharif-ul-Ulama Mazandarani in 1830 as well as the repression of the Shia population by the Ottomans in 1843 both played a significant role in the relocation of many scholars to the city of Najaf and thus Najaf subsequently became the center of Shia Islamic leadership and education.[65] Today the Hawza Seminary still exists in Karbala (such as the School of Allamah Bin Fahd) but to a lesser extent in comparison to Najaf.

Infrastructure

editAirports

editAirports in Karbala include:[66]

- Karbala Northeast Airport[67]

- Karbala International Airport[68] (located to the southeast of Karbala)

Inter-city high-speed railway system

editIn February 2024, the Iraqi National Investment Commission (NIC) unveiled a project to construct an inter-city high-speed rail connecting the cities of Karbala and Najaf. Once finished, it is set to accommodate up to 25,000 passengers per hour.[69][70]

International relations

editSister cities

editAs of 2024, Karbala has 4 sister cities:

See also

editExplanatory notes

editReferences

edit- ^ "Iraq: Governorates & Cities".

- ^ "Karbala". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Karbala". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ^ "Karbala". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Karbalā'". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Iraq: Livelihoods at risk as level of Lake Razaza falls". IRIN News. 5 March 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ a b Under Fire: Untold Stories from the Front Line of the Iraq War. Reuters Prentice Hall. January 2004. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-13-142397-8.

- ^ "Karbala, Iraq Metro Area Population 1950-2024". www.macrotrends.net. Retrieved 2024-06-18.

- ^ Shimoni & Levine, 1974, p. 160.

- ^ Aghaie, 2004, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Malise Ruthven (2006). Islam in the World. Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780195305036.

- ^ a b David Seddon (11 Jan 2013). Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East. Karbala (Kerbala): Routledge. ISBN 9781135355616.

- ^ a b John Azumah; Dr. Kwame Bediako (Foreword) (26 May 2009). My Neighbour's Faith: Islam Explained for African Christians. Main Divisions and Movements Within Islam: Zondervan. ISBN 9780310574620.

- ^ Paul Grieve (2006). A Brief Guide to Islam: History, Faith and Politics: The Complete Introduction. Carroll and Graf Publishers. p. 212. ISBN 9780786718047.

- ^ Paul Grieve (2006). A Brief Guide to Islam: History, Faith and Politics : the Complete Introduction. Carroll and Graf Publishers. p. 212. ISBN 9780786718047.

- ^ "Interactive Maps: Sunni & Shia: The Worlds of Islam". PBS. Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ^ a b al-Qummi, Ja'far ibn Qūlawayh (2008). Kāmil al-Ziyārāt. Translated by Sayyid Mohsen al-Husaini al-Mīlāni. Shiabooks.ca Press. p. 545.

- ^ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir – History of the Prophets and Kings; Volume XIX The Caliphate of Yazid ibn Muawiyah, translated by I.K.A Howard, SUNY Press, 1991

- ^ a b c Khatab, Sayed (2011). Understanding Islamic Fundamentalism: The Theological and Ideological Basis of Al-Qa'ida's Political Tactics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-977-416-499-6. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ Juan Cole, Sacred Space and Holy War, IB Tauris, 2007 p. 71–72

- ^ Staff writers. "The Saud Family and Wahhabi Islam, 1500–1818". www.au.af.mil. Archived from the original on March 17, 2004. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ Martin, Richard C., ed. (2003). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim world ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). New York: Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 0-02-865603-2. OCLC 52178942.

- ^ Litvak, Meir (2010). "KARBALA". Iranica Online.

- ^ Vassiliev, Alexei (September 2013). The History of Saudi Arabia. Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-779-7. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ Cole, Juan R.I. and Moojan Momen. 1986. "Mafia, Mob and Shiism in Iraq: The Rebellion of Ottoman Karbala 1824–1843." Past & Present. No 112: 112–143.

- ^ Cole, Juan R. I. Sacred Space and Holy War: The Politics, Culture and History of Shi'ite Islam. London: I.B. Tauris, 2002.

- ^ "A Failed Manipulation: The British, the Oudh Bequest and the Shī'ī 'Ulamā' of Najaf and Karbalā'." Meir Litvak, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, JSTOR 826171

- ^ Tauber, Eliezer (2014-03-05). The Arab Movements in World War I. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 9781135199784.

- ^ Report by His Britannic Majesty's Government to the Council of the League of Nations on the Administration of Iraq 1927–28. p. 177. Retrieved 2020-07-17 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Mattis, James N., 1950– (2019). Call sign chaos : learning to lead. West, Francis J. (First ed.). New York. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8129-9683-8. OCLC 1112672474.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Hamourtziadou, Lily (2007-04-15). "A Week in Iraq". iraqbodycount.org. Archived from the original on 2007-04-29. Retrieved 2007-04-15.

- ^ "Iraqi Shia pilgrims mark holy day". 19 January 2008 – via bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Karbala". United Nations. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020: Kerballa" (CSV). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ a b Quran 10:98

- ^ a b Summarized from the book of story of Muhammad by Ibn Hisham Volume 1 pg.419–421

- ^ a b "Three Day Fast of Nineveh". Syrian orthodox Church. Archived from the original on 2012-10-25. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Tabatabaei, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1979). Shi'ite Islam. Suny Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-87395-272-9.

- ^ al-Qummi, Ja'far ibn Qūlawayh (2008). Kāmil al-Ziyārāt. Translated by Sayyid Mohsen al-Husaini al-Mīlāni. Shiabooks.ca Press. pp. 66–67.

- ^ "Kadhimiya". Encyclopaedia of Iranian Architectural History (in Persian). Archived from the original on 3 October 2015.

- ^ "History of the Shrine of Imam Ali al-Naqi & Imam Hasan Al-Askari, Peace Be Upon Them". Al-Islam.org. Archived from the original on 23 February 2006. Retrieved 23 February 2006.

- ^ "Unesco names World Heritage sites". BBC News. 2007-06-28. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Quran 26:160

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon M. (2002). Prophets in the Quran: an introduction to the Quran and Muslim exegesis. Comparative Islamic studies. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 1–393. ISBN 978-0-8264-4957-3.

- ^ a b History of Islam, volume 1, by Professor Masudul Hasan.[page needed][edition needed]

- ^ a b Quran 21:51

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild (3 October 2023). "Mesopotamian religion". Britannica.com.

- ^ Quran 11:44

- ^ Quran 23:23

- ^ J. P. Lewis, Noah and the Flood: In Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Tradition, The Biblical Archaeologist, December 1984, p.237

- ^ Quran 2:102

- ^ Morris Jastrow, Ira Maurice Price, Marcus Jastrow, Louis Ginzberg, and Duncan B. MacDonald; "Babel, Tower of", Jewish Encyclopedia; Funk & Wagnalls, 1906.

- ^ al-Qummi, Ja'far ibn Qūlawayh (2008). Kāmil al-Ziyārāt. Translated by Sayyid Mohsen al-Husaini al-Mīlāni. Shiabooks.ca Press. p. 534.

- ^ Amali by Shaykh Tusi, vol. 1 pg. 326

- ^ Mustadrakul Wasail, vol. 10, pg 339-40 tradition 2; Jadid Makarimul Akhlaq pg.189; Beharul Anwaar vol. 101, tradition 60

- ^ "Iraq's holy cities enjoy boom in religious tourism". Al Arabiya. 4 April 2013.

- ^ منارة موجدة «مَعلَمٌ حددت وظيفته تسميته». Al-Shirazi. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ الآثار منارة موجدة. Holy Karbala. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ (Re-)defining Some Genre-Specific Words: Evidence from some English Texts about Ashura, Muhammad-Reza Fakhr-Rohani, University of Qom, Iran

- ^ A citation from Fruzzetti, "Muslim Rituals," for this use of Karbala is as follows: "The Muslims then proceed to 'Karbala' to bury the flowers which were used to decorate the tazziyas, the tazziyas themselves being kept for the next year's celebration." (pp. 108–109).

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris; Vernoit, Stephen (2006). Islamic Art in the 19th Century: Tradition, Innovation, And Eclecticism. BRILL. ISBN 9004144420. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ^ "Karbala University: A General View". University of Karbala. Archived from the original on 2017-10-10. Retrieved 2017-04-21.

- ^ "Ahl Al Bayt University Website". Ahl Al Bayt University. Retrieved 2019-11-23.

- ^ Ali Tekmaji (September 20, 2017). "Karbala opens new advanced academic university". Imam Hussein Holy Shrine (International Media). Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ^ Litvak, Meir (1998). Shi'i Scholars of Nineteenth Century: The Ulama of Najaf and Karbala. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–141. ISBN 0-521-62356-1.

- ^ "$500 Million Airport Scandal Exposes Industrial Scale Corruption in Holy Karbala". Foreign Relations Bureau – Iraq. 2017-03-07. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- ^ "Karbala Northeast (Imam Hussein) Airport". CAPA Centre for Aviation. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- ^ MEED. Vol. 42. Economic East Economic Digest. 2018. pp. 38–48.

- ^ "Iraqi government opens two rail project tenders". Railway Technology.

- ^ "Work on high-speed train project linking Holy Karbala to Holy Najaf to begin soon, ministry says". ShiaWaves.

- ^ "Town Twinning". mashhad.ir. Mashhad. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- ^ "Tomb of Kamal-ol-Molk". Iranparadise.

- ^ "Qom". toiran.com. Toiran.com. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- ^ "Tabriz and Shanghai agree to be sister cities". tabriz.ir. Tabriz. 2019-05-06. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

Further reading

editPublished in the 19th century

edit- Louis de Sivry, ed. (1859). "Karbala". Dictionnaire geographique, historique, descriptif, acheologique des pèlerinages anciens et modernes (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Published in the 20th century

edit- Peters, John Punnett (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). pp. 753–754.

Published in the 21st century

edit- C. Edmund Bosworth, ed. (2007). "Karbala". Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

- Michael R.T. Dumper; Bruce E. Stanley, eds. (2008), "Karbala", Cities of the Middle East and North Africa, Santa Barbara, USA: ABC-CLIO

External links

edit- Shia Shrines of Karbala – Sacred Destinations

- Shia Karbala Poetry Archived 6 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Karbala – A Lesson for Mankind (archived)

- Karbala Quotes and Sayings

- Karbala and Martyrdom

- Karbala – The Facts and the Fairy-tales

- Karbala, the Chain of Events