I do not enjoy Facebook — I find it cloying and impossible — but I am there every day. Last year I watched a friend struggle through breast cancer treatment in front of hundreds of friends. She broadcast her news with caution, training her crowd in how to react: no drama, please; good vibes; videos with puppies or kittens welcomed. I watched two men grieve for lost children — one man I’ve only met online, whose daughter choked to death; one an old friend, whose infant son and daughter, and his wife and mother-in-law, died in an auto accident.

I watched in real time as these people reconstructed themselves in the wake of events — altering their avatars, committing to new causes, liking and linking, boiling over in anger at dumb comments, eventually posting jokes again, or uploading new photos. Learning to take the measure of the world with new eyes. No other medium has shown me this in the same way. Even the most personal literary memoir has more distance, more compression, than these status updates.

In the world of social media, it can feel bizarre that potent evidence of grieving from one friend is followed so quickly by pictures of oven-fresh cookies from another. But Facebook is generated by algorithms without feelings. It’s not a narrative: The breast cancer went into remission, but the stories of the radiation treatment continue; the lost children remain as photos, woven into the threads of hundreds of lives. The details of everyday life begin to fill in around those threads. The tide brings in status updates; the tide takes them out.

Social media has no understanding of anything aside from the connections between individuals and the ceaseless flow of time: No beginnings, and no endings. These disparate threads of human existence alternately fascinate and horrify that part of the media world that grew up on topic sentences and strong conclusions. This world of old media is like a giant steampunk machine that organizes time into stories. I call it the Epiphanator, and it has always known the value of a meaningful conclusion. The Epiphanator sits in midtown Manhattan and clunks along, at Condé Nast and at the Times and in Rockefeller Center. Once a day it makes a terrible grinding noise and spits out newspapers and TV shows. Once a week it spits out weeklies and more TV shows. Once a month it produces glossy magazines. All too often it makes movies, and novels.

At the end of every magazine article, before the “■,” is the quote from the general in Afghanistan that ties everything together. The evening news segment concludes by showing the secretary of State getting back onto her helicopter. There’s the kiss, the kicker, the snappy comeback, the defused bomb. The Epiphanator transmits them all. It promises that things are orderly. It insists that life makes sense, that there is an underlying logic.

To defend its realm, this machine sends its finest knights to crusade against this kraken rising from a sea of status updates. Zadie Smith, in The New York Review of Books: “When a human being becomes a set of data on a website like Facebook, he or she is reduced … Our denuded networked selves don’t look more free, they just look more owned.”

“I have a lot of opinions on social media that make me sound like a grumpy old man sitting on the porch yelling at kids,” said Social Network screenwriter Aaron Sorkin recently. “There’s no depth. Life is complicated. You need to be able to explain complexity.”

Outgoing Times executive editor Bill Keller:

The shortcomings of social media would not bother me awfully if I did not suspect that Facebook friendship and Twitter chatter are displacing real rapport and real conversation, just as Gutenberg’s device displaced remembering.

“Real rapport,” “real conversation,” “complexity,” and “depth,” could be code words for “an appropriate level of respect.” Sociologist Zeynep Tufekci disputed Keller’s claim that time spent on social networking comes at the expense of “in person,” backed it up with links to research — and did it on Twitter.

The Epiphanator’s most recent broadside appeared on a recent Sunday when the Times published Jonathan Franzen’s commencement speech at Kenyon College. The title, damning in itself, was “Liking Is for Cowards. Go for What Hurts” — a variation on Keller’s theme of genuineness. But far, far more likely to induce rage.

There should be a word for that feeling you get when an older person — and not much older, so quickly are things changing — shames him or herself by telling young people how to live. I’d vote for Bedeutungslosigkeitschmach, or “irrelevance shame,” (made up with the help of Google translate) or perhaps Rünschmerz, the horrifying gut pain one experiences watching Andy Rooney. Whatever it’s called, Franzen brought it in buckets.

He took us to task for “liking” but not loving. He questioned all the devices that command our affection. “Good people of Kenyon and the Sunday Times,” he cried, “Return to your woodsy cottages and take pleasure in honest things: The bark of a fox; the nose of unspiced wine; the honest friendship of Alice Sebold; and a gristly, capital-L-Love-LOVE, honest and true with a great deal of hair and stink.”

That’s my version. What he actually wrote was: “To speak more generally, the ultimate goal of technology, the telos of techne, is to replace a natural world that’s indifferent to our wishes — a world of hurricanes and hardships and breakable hearts, a world of resistance — with a world so responsive to our wishes as to be, effectively, a mere extension of the self.”

He tells the Kenyon 21-year-olds, who were likely texting throughout the ceremony, that they need more love. If the sub-30-year-olds with whom I’ve worked are typical, these young men and women love — each other, or bands, or ideas — too much, they love too often, with a feral intensity and with the constant assistance of mobile devices. Maybe what he was telling them is that they should be more old.

Franzen’s speech recalls another, very different commencement speech, by Apple CEO Steven Jobs to the 2005 class of Stanford. Jobs is the embodiment of California, all gold rush, less city-on-hill. At Stanford he invoked the Whole Earth Catalog as “one of the bibles of my generation” — its cut-and-paste aesthetic, hippie cheer, and promise of access to information a balm for his late-adolescent soul. The Whole Earth Catalog was a DIY-bible assembled by former Merry Prankster Stewart Brand, far from the clanking Epiphanator. “We are as gods,” reads the preface, “and we might as well get good at it.”

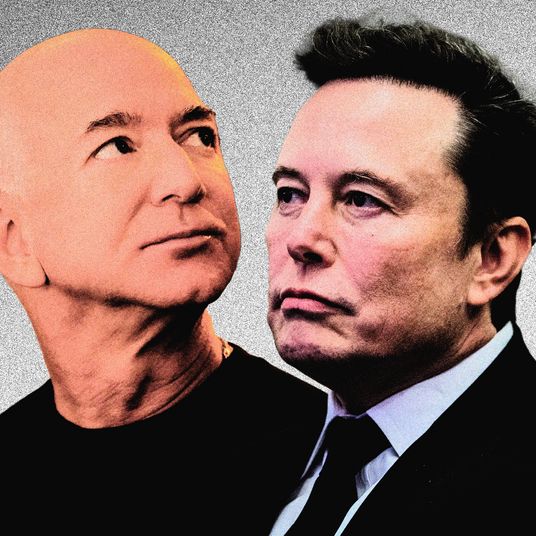

The Whole Earth Catalog’s descendants include, in strange but real ways, the entire computer and Internet industries. Creating tools to give regular people godlike powers is exactly what Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Tim Berners-Lee, Mark Zuckerberg, and a host of others have done, starting with cheap computer hardware and shrink-wrapped software, then via the web and on social networks. We’ve reached a point where anyone with an SMS card or access to an Internet café can potentially be heard by billions of people. What could be more godlike — or more foreign to the Epiphinator — than that?

And how do the Whole Earth heirs of Silicon Valley stand today compared to their financially bereft Epiphonatorian counterparts? Apple couldn’t get much bigger without selling oil, while the media industry has been reduced to dime-size buttons that show up on iPhone screens. Google regularly announces initiatives to “save” the newspaper and book industries — like a modern-day hunter who proclaims himself a conservationist. And Facebook, having already swallowed up enormous chunks of discretionary media consumption time, has its old-school media counterparts chasing after “Likes” as if they were cocaine being dispensed in a lab rat’s cage.

So it would be easy to think that the Whole Earthers are winning and the Epiphinators are losing. But this isn’t a war as much as a trade dispute. Most people never chose a side; they just chose to participate. No one joined Facebook in the hope of destroying the publishing industry.

As someone with Franzendentalist roots and Epiphinator tendencies, who consumes too many hours of social media, I keep sensing some serious hurt feelings from the older-media side — “Why would you love that thing instead of me?” They act like my wife would if I brought home a RealDoll. But it’s not like that. I don’t think people love Twitter or Facebook in the same way they might love Parks and Recreation or Twilight. Rather, we like the beer and tolerate the bottle. And even if we have those other browser tabs open, we’re still hungry for endings.

Obviously, the Epiphinator will need to slim down in order to thrive, but a careful study of history shows how impossible it is to determine whether it can return to both power and glory, or whether its demise is imminent.

The phonograph killed the player piano; radio, newspapers, and TV happily co-existed for generations. When did you last think fondly on the DuMont television network, or smile in recall of Friendster? This moment of anxiety and fear will pass; future generations (there’s now one every three or four years) will have no idea what they missed, and yet they will go on, marry, divorce, and own pets.

They may even work in journalism, not in the old dusty career paths, but in the new jobs and niches carved out by some of the people New York has selected for its New Media Innovators list. Viral meme tracker, slideshow specialist, headline optimizer — these are jobs that didn’t exist a few years ago, and while they may seem a million miles from journalism as we know it, they will be components of the future Epiphinator.

We’ll still need professionals to organize the events of the world into narratives, and our story-craving brains will still need the narrative hooks, the cold opens, the dramatic climaxes, and that all-important “■” to help us make sense of the great glut of recent history that is dumped over us every morning. No matter what comes along streams, feeds, and walls, we will still have need of an ending.